Feb 9, 2015

For the past year, I have been working closely with Jad Abumrad and the team at RadioLab on a fascinating story about Facebook.

The story centers on the work of Arturo Bejar, who is one of the technical leaders at the company, and a team of engineers, product developers and external social scientists who collectively operate under the banner of the Compassion Research Group. Together, this team is studying how our ancient human capacities for conflict, compassion, respect, trust, and empathy are expressed by people on Facebook; based on these findings, they’re reworking the service’s interface to encourage more humane relationships among its 1.3 billion users.

In addition to exploring our digital relationships and emotions, the Facebook story also touches on the ways in which our online lives are continuously experimented upon; the new ways social scientists are exploring ancient questions with ‘big data’; and the ethical considerations that such inquiries inevitably raise. Social media is changing social science, and at Facebook, we caught a glimpse of its future.

For space and flow reasons, one particularly intriguing example of this work didn’t get an in-depth airing in the radio piece, and I thought I’d relate it here more fully.

The story actually begins all the way back in 1859, with the publication of Charles Darwin’s landmark treatise, On the Origin on Species. In that book, Darwin famously lays out the argument that species evolve over the course of generations, through the process of natural selection. At the time, most scientists, not to mention most people, were creationists who believed that the great diversity of Life was part of a natural and unchanging order, over which God had given us dominion. Accordingly, Darwin left the natural conclusion of his argument – that human beings evolved via the same mechanism as all other species – largely unstated. (Except, for a single, telling line at end of the book: “light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”)

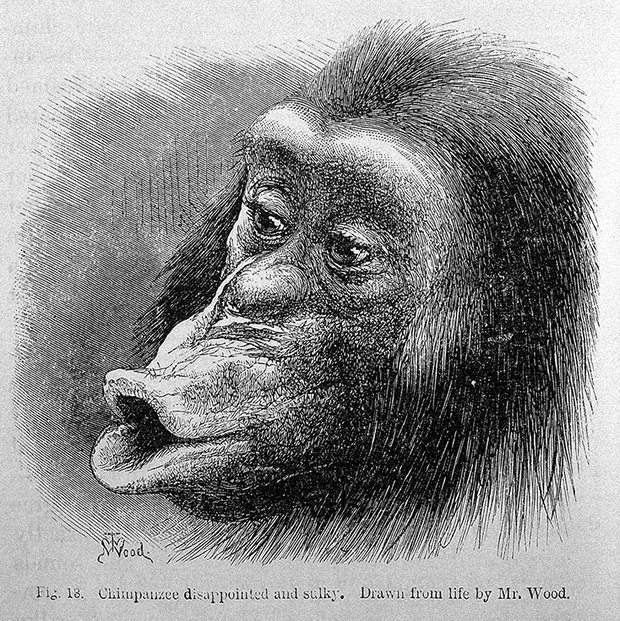

Darwin didn’t publish his own fuller views on human evolution until more than a decade later, with two works that came in rapid succession, The Descent of Man (in 1871) and The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (in 1872).

In first of these books, Darwin argued, to no one’s surprise, that human beings did indeed evolve from a common hominid ancestor. In the second book, however, he presented an argument not just about the origins of our species, but of our psyches.

His argument spoke to what was, both in Darwin’s time and our own, a commonly held view: that our emotional life – marked by feelings like grief, envy, tenderness, love, guilt, pride, and affirmation – is uniquely human. If our emotions are unprecedented, so the thinking went, then we must be, too.

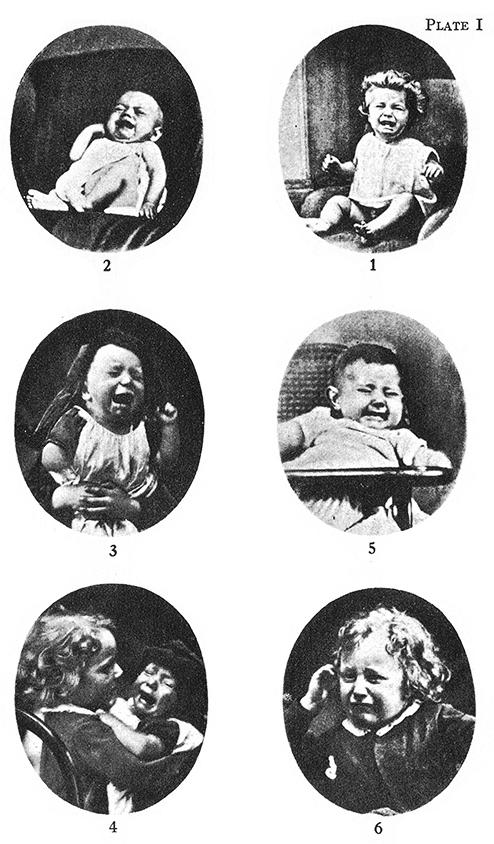

To debunk this idea, Darwin presented a detailed taxonomy of forty distinct emotions, ranging from “high spirits” such as joy, to the “low” spirits” such as despair, and concluded with the more complex emotions such as shame. Then he painstakingly documented how these emotional expressions have consistent physiological roots. Everywhere, people use the same thirty muscles in our faces to pull our lips up into a smile, knit our forehead into a frown, distort our cheeks into a grimace of psychic pain, bow our heads in supplication, and tilt our necks to signal puzzlement.

Darwin argued that these emotional expressions are not just universal across cultures, but have their roots in purposeful, and similar, animal behaviors across many mammalian species. A Chimpanzee uses similar muscle groups to purse its lips as we do, and often for the same reasons. We’re not as different – or as special – as we might suppose.

With this argument, Darwin helped advance the field of evolutionary psychology and usher forth the robust scientific study of emotional experience. His basic thesis has been elaborated, refined, studied and debated ever since.

Researchers subsequently confirmed that human beings in both Western and non-Western societies can indeed consistently recognize a core subset of Darwin’s facial expressions. In 1967, psychologist Paul Ekman, perhaps the most well known contemporary figure in emotions research, went so far as to show these expressions to an isolated community in Papua New Guinea, who had never seen modern movies or television. They were able to identify the expressions without difficulty. Other studies have shown that our autonomic nervous system responds in consistent ways when we see Darwinian expressions of emotion – further evidence that they’re hard-wired into our biology.

Yet critics point out that both the subjective experiences and physical expressions associated with supposedly ‘basic’ emotions can vary widely even within a category. One person might stutter when enraged, while another lets loose an eloquent stream of epithets; one person might blush with quiet pride at an accomplishment, while another roars like an NFL star in the endzone.

To critics, this variability suggests that emotions are as much cultural signals as they are biological ones. To stereotype for a moment (for rhetorical purposes only - no letters, please!): is the Southern Italian, who wildly gesticulates with his hands as he talks, really using the same innate, emotional vocabulary as the famously stoic Swede? Is the facially impassive, but verbally expressive Japanese businessman really wired the same way as the ironic Brooklyn hipster? Doesn’t this variety suggest that our emotional lives are substantially, if not entirely, a matter of culture?

And, if that’s the case, why should it matter that everyone in the world can associate a smile with happiness, if people in your particular society don’t actually make a habit of smiling when they’re happy?

Here, we return to Facebook, and to the work of the Compassion Research Group. One of its leading members is the Berkeley psychologist Dacher Keltner, who co-directs that university’s aptly-named Greater Good Science Center. A former student and colleague of Ekman, Keltner’s research explores the roots of human goodness, particularly compassion, awe, love, and beauty, and how they are communicated through means of gestures, touch and expression.

During their work together, Arturo Bejar approached Keltner with an intriguing proposition: would he be interested in using what had been gleaned in the scientific study of emotions to design a ‘sticker pack’ for Facebook?

Stickers are widely-used animated icons (often of the human face or common objects) used to add expressiveness to otherwise bland text chats – think of them as more sophisticated versions of emoticons, like the “:-)”smiley face that some of us embed in our emails. Here was a chance to use Darwin’s insights to enhance the emotional content the online communications of millions of people around the world.

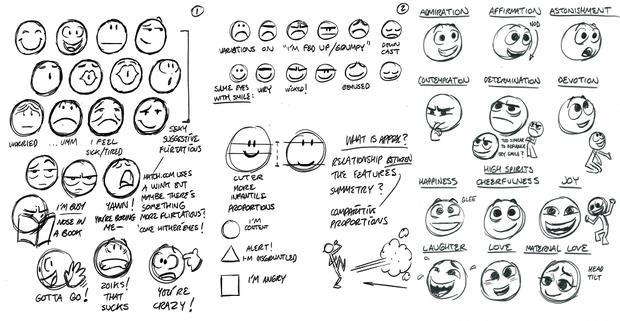

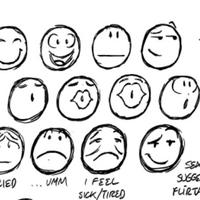

So Keltner turned to Matt Jones, an animator at Pixar Studios (yes, that Pixar) and gave him the job of designing 51 animated faces, mostly derived from Darwin’s original emotional taxonomy. The full list included admiration, affirmation, anger, anxiety, astonishment, awe, boredom, confusion, contemplation, contempt, contentment, coyness, curiosity, desire, determination, devotion, disagreement, disgust, embarrassment, enthusiasm, fear, gratitude, grief, guilt, happiness, high spirits, horror, ill temperment, indignant, interest, joy, laughter, love, maternal love, negation, obstinateness, pain, perplexity, pride, rage, relief, resignation, romantic love, sadness, shame, sneering, sulkiness, surprise, sympathy, terror, and weakness.

To succeed online, Jones’ sticker designs would have to consistently communicate these emotions without benefit of a label, and in very different parts of the world. End-users would have to be able to look at the sticker for ‘happiness’ or ‘maternal love’ and identify it as such. To ensure the stickers performed as expected, Keltner and his colleagues took Jones’s prototype designs and independently tested them with research subjects in two very different societies: the United States and China.

Overall, both the Chinese and American subjects had roughly the same accuracy, correctly identifying 42 of the 51 distinct emotions presented. Cultural differences did appear: the Chinese were better able to recognize negative emotions, while the Americans were better able to identify positive ones. Yet Jones’ designs universally communicated the most extensively-researched emotions like anger, disgust, fear, sadness, surprise, and happiness, as well as more recently-studied ones like embarrassment, pride, desire, and love – and even a few emotions that hadn’t been studied before, like contemplation, coyness, astonishment, boredom, and perplexity.

With these results in hand, Keltner and his colleagues turned Jones’ now-tested illustrations over to Facebook’s designers, who used the best performing ones to create a new sticker pack called Finch, named after the finches Darwin had famously encountered in the Galapagos Islands. Finch contains sixteen cross-culturally tested animations of emotions based on Jones’ original designs.

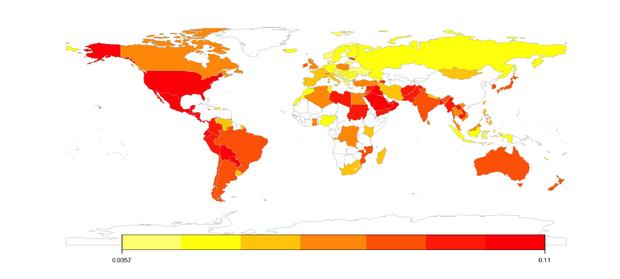

As the stickers were made available on Facebook, downloaded and then used in chats by millions of users around the world, the Compassion Research team could now look at how they were being used – not by specific users, but in the aggregate. How much ‘love’ was being expressed with the stickers in each country, on a per-capita basis? Or ‘anger’? Or ‘sympathy’? Did different cultures vary in terms of the types of emotional stickers they use? Over time, the researchers realized they could use such analysis to take the emotional temperature of a sizeable portion of the planet.

Clear patterns emerged in the data. Italians, South Africans, Russians and Brazilians had ‘Cultures of Love’ – sending lots of amorous stickers. The U.S. and Canada were similar in most of their usage patterns – though the Canadians were vastly more ‘sympathetic’, while the Americans were ‘sadder’. And the use of ‘deadpan’ stickers predominated across North Africa and the Middle East.

The picture got even more interesting when the researchers correlated the usage of the Finch stickers with other social indicators. Countries that expressed the most ‘awe’ online gave more to charity offline. And countries that expressed the most ‘happiness’ were not actually the happiest in real life. Instead, it was the countries that used the widest array of stickers that that did better on various measures of societal health, well-being – even longevity. “It’s not about being the happiest,” Keltner told me, “it’s about being the most emotionally diverse.”

These are intriguing correlations – and so far, they’re just that. We have to be careful not to over-extrapolate or conflate the measure of the thing for the thing being measured. Clicking on a sticker to express a belly laugh is not quite the same thing as having an actual belly laugh. And while there are now more Facebook users than Catholics worldwide, there are still more people who’ve never been online than have ever been on Facebook. (One wonders how their inclusion would skew the data.)

Still, this is clearly the beginning of a tantalizing and unprecedented social science revolution, one that will reveal previously impossible assessments of the global psyche, and perhaps shift the dialogue about the relationship between nature and culture. And one wonders what else might consistently correlate with our global emotional weathermap. The stock market, maybe? Or social revolution? Or world peace?

How does that make you feel?