Nov 15, 2011

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert. Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. And today ...

ROBERT: It's patient zero. That's our subject.

JAD: Yeah, and this next story, whew!

ROBERT: It's so huge.

JAD: It's the ultimate patient zero story, really.

ROBERT: Many of us have lived through this. It was—it's as recent an event—it's such a recent event that it still hurts and it still bleeds.

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: And in it somewhere is a—literally, the—the patient that is called Zero. So this is ...

JAD: Yeah. A lot of people are gonna help us tell the story, but starting us off is science writer, Radiolab regular Carl Zimmer.

CARL ZIMMER: So in 1981, doctors for the first time described ...

[NEWS CLIP: A mysterious newly-discovered disease ...]

CARL ZIMMER: A syndrome.

[NEWS CLIP: ... which affects mostly homosexual men.]

CARL ZIMMER: The young men in Los Angeles ...

JAD: Were dying.

[NEWS CLIP: The number of cases has been growing faster and faster.]

[NEWS CLIP: So far, more than 80 Americans have died.]

[NEWS CLIP: 258 people have died.]

[NEWS CLIP: 625 people have died.]

JAD: Of course, this is the part we all know. How, from those first few cases in LA, AIDS became one of the deadliest pandemics the world has ever seen.

[NEWS CLIP: More dangerous than the plague of the Middle Ages.]

JAD: But back at the beginning, there was a story that I've not been able to shake for the last 30 years. And it's a story that I want to re-imagine right now.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Right after news of this syndrome started to break ...

JAD: That's science writer David Quammen, who along with Carl will be one of our guides.

CARL ZIMMER: Epidemiologists were trying to figure out where ...

[NEWS CLIP: Where did it come from?]

CARL ZIMMER: And they were thinking like, "Well, maybe it's a sexually-transmitted disease.

JAD: So the CDC launches a study.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Of a group of about 30 patients.

JAD: Gay men.

DAVID QUAMMEN: In New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, to see who had had sexual contact with whom.

JAD: How do you—is that just a series of interviews with people?

CARL ZIMMER: Yeah. Please name all the people that you—that you've slept with.

JAD: The CDC eventually releases the results of this survey in the form of a diagram.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Like a network drawing with circles representing patients, and then lines representing sexual contact.

JAD: And each patient, each little circle was numbered.

DAVID QUAMMEN: New York, seven. Los Angeles, twelve.

JAD: So you didn't know who was who, but you could tell immediately when you look at this thing, that of all the 30 or so circles, there was one circle that was special. It had lines coming out in every direction.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Seven or eight emanating from him.

JAD: Like the hub of a wheel, except all the spokes on this wheel connected to other wheels which then shot out and connected to other wheels, fanning outward. And at the center of it all was that one little circle, numbered ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Zero. Number zero.

JAD: As far as we know, that was the first time that you ever get the term 'patient zero.'

[60 MINUTES CLIP: Patient zero was a man, the central victim and victimizer.]

JAD: This is from a 60 Minutes special in 1988. That year a reporter named Randy Shilts had written a book called And The Band Played On that for the first time revealed the identity of patient zero.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: He was a French-Canadian.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: A very handsome airline steward.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: Named Gaëtan Dugas.]

DAVID QUAMMEN: Gaëtan Dugas.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: Patient zero.]

JAD: A few minutes later in the report, Shilts comes on to describe a guy ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: A guy who has got unlimited sexual stamina.]

JAD: This sexual athlete who would fly from one hot spot to the next because of his job, having sex with literally thousands of men.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And as he knew he was dying, at least according to Randy Shilts, he became somewhat sinister and malicious. He would sleep with a male partner at a bathhouse in San Francisco or somewhere else. And then when the light came up, according to Randy Shilts, he would say, "I've got gay cancer."

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: "Now you're gonna get it too."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: You talked to him?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: I talked to him, yeah.]

JAD: This is Dr. Selma Dritz. She was part of that CDC study.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, 60 Minutes: I told him that he was getting other people sick with it. And he said, "It's my right to do whatever I want. My civil rights. I do as I please. I've got it, why shouldn't they have it?" I said, "You can kill yourself if you want but you got no right to take somebody else along with you." And he said, "Screw you," and walked out.]

DAVID QUAMMEN: Really, a chilling moment.

JAD: And pretty much from that moment on, Gaëtan Dugas ...

CARL ZIMMER: He just took on this—this aura as single-handedly causing an epidemic in the United States.

JAD: Now I don't know about you, but I first bumped into this story in the movie version of And The Band Played On.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, And the Band Played On: My friend, we're talking about thousands of men whose faces I cannot even remember and you want names.]

JAD: That's an actor playing Gaëtan Dugas in the movie. Now when I first saw that, AIDS had already infected two and a half million people. And to think that it could all go back to this one guy just seemed unreal.

CARL ZIMMER: It was a—it was a very potent story. There's no doubt. And—and he gave HIV to a lot of people, there's no question about that. But what we do know is that he was not patient zero.

JAD: He was not patient zero.

CARL ZIMMER: No.

DAVID QUAMMEN: He was not the beginning point.

CARL ZIMMER: He wasn't.

JAD: Not even close.

ROBERT: Huh.

JAD: So here's the question that got me started on this story. Okay, so the gay steward, that was the movie stuck in my head. But what's the real movie? What movie can we make about the beginning of the AIDS epidemic? Because when you've got something so vast that, according to some estimates, will have killed 60 million people by the end of the decade, you need a beginning. You need some way of explaining how this disaster happened—and how it might happen again.

ROBERT: And how exactly do we know that Gaëtan Dugas wasn't patient zero?

CARL ZIMMER: Well, there are a couple reasons we know it. So—so one thing that people started to do ...

JAD: Scientists.

CARL ZIMMER: ... was to—they went, started going back and looking at people who had died.

DAVID QUAMMEN: People who died mysteriously ...

CARL ZIMMER: ... of AIDS-like things.

JAD: In the past.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Might some of them have been early cases?

CARL ZIMMER: And they started finding a lot.

[NEWS CLIP: Robert Rayford had AIDS 12 years before it was recognized in this country in 1981.]

[NEWS CLIP: In 1959, a sailor in Britain died of pneumocystis pneumonia.]

JAD: And so for a while, you had all these new patient zeros.

[NEWS CLIP: In 1961, a nurse in Chicago died of Kaposi's sarcoma.]

CARL ZIMMER: But the real definitive blow to this whole patient zero nonsense came by actually looking at the virus itself.

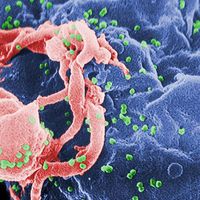

JAD: In 1984, same year that Gaëtan Dugas died, scientists isolate the virus.

CARL ZIMMER: HIV.

JAD: Which is really just a little string of genetic code that gets into your body and into your cells and uses your cells to make copies of itself. But here's the thing.

DAVID QUAMMEN: When it replicates within a single patient, it copies itself imprecisely. It mutates quickly. It changes a lot.

JAD: As the virus duplicates itself inside a person, the dupes often have little copying errors in them, little mutations. And it turns out, those errors? They happen at a predictable rate. You can kind of almost predict how many you're gonna see in a year or five years. And so the amount of changes that you see out there, the diversity, really, of the viruses in the AIDS population, well that becomes really good information. And so a group of scientists began to look at ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: The amount of diversity among HIV patients in the US.

CARL ZIMMER: And other parts of the world.

ROBERT: And the more diversity, the longer the virus has been around.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Right. Right.

CARL ZIMMER: And they could use that kind of like a clock. If you have a virus here and a virus there ...

JAD: You could measure how different they are, and you would know that it would take a certain amount of time for them to get that different. And to make a long story short ...

CARL ZIMMER: The picture they get is ...

JAD: That AIDS entered the United States ...

CARL ZIMMER: Around 1966.

DAVID QUAMMEN: At a time when Gaëtan Dugas was still a virginal adolescent.

JAD: From there, scientists were able to trace the virus back to Haiti and from Haiti back to Africa.

CARL ZIMMER: It's been there the longest. It's had the longest time to become diverse, to mutate, to evolve. So if you want to really—if you want to get to the real patient zero as it were, the most interesting stuff come—actually comes from Africa. So one way to try to figure out its origins there is to go looking for the virus.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Yep. And that takes us back to ZR 59 and DRC 60. Can we talk about them?

ROBERT: Sure.

JAD: What?

DAVID QUAMMEN: These are the two earliest known HIV-positive human specimens.

JAD: And this is where for me at least, the story gets way bigger than I imagined. Now, the first sample ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: ZR 59.

JAD: Came to light in the late-'90s. Somehow, scientists unearthed a very old tube of blood from a hospital in Kinshasa in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And when they tested it ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: It had HIV. This had been taken from a Bantu man in 1959.

ROBERT: 1959!

DAVID QUAMMEN: Yeah. Nobody knows his name. Nobody even knows, I think, what he died of. And that was the only one for a number of years.

MICHAEL WOROBEY: That was our one glimpse into the kind of deep history of HIV.

JAD: But then along comes that guy, Michael Worobey. He's an evolutionary biologist at the University of Arizona. And a few years ago, Michael went back to Kinshasa and found a second HIV sample. He actually found the virus lurking in a tiny bit of human tissue that was preserved in paraffin wax.

MICHAEL WOROBEY: It's kind of like Han Solo in the Star Wars movie when he's kind of frozen in that carbonite or whatever that stuff is.

JAD: In this new sample, it was from the same town, Kinshasa, as the first. And also more importantly, from the same time.

MICHAEL WOROBEY: 1960. And with the two of them, then you can kind of go back in time.

JAD: Like we described before, you can measure the differences between the samples, calculate how long it would take for those samples to get that different. And in the end, you can use these two samples to wind the clock all the way back to the virus that started it all. And it turned out ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: The most recent common ancestor of those two specimens ...

JAD: Goes back to ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: ... to about 1908.

JAD: 1908. That is when it started in human beings.

ROBERT: What? 1908? Is that what he said?

JAD: Well, roughly.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Give or take a margin of error.

CARL ZIMMER: Early 1900s.

JAD: So around 1908, give or take, something happened.

DAVID QUAMMEN: That's right. That moment is the spillover.

ROBERT: Spillover.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Spillover's the term that scientists use to describe the moment when a virus in one species passes into another species.

CARL ZIMMER: You know, new diseases in humans tend to pop up from animals. So people said, "Okay, flu comes from birds. Where does HIV come from?" To get at that answer, you have to look beyond human beings. You have to look at other viruses that are like HIV.

DAVID QUAMMEN: So the search was on.

[NEWS CLIP: The inability to find a similar disease in research animals.]

JAD: Turns out, right about the time that the HIV virus was discovered ...

[NEWS CLIP: Scientists at the New England Primate Research Center ...]

JAD: Some researchers found a virus like it in macaque monkeys.

[NEWS CLIP: Macaque monkey.]

JAD: In fact, it was so similar that they called it ...

CARL ZIMMER: SIV.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Simian immunodeficiency virus.

BEATRICE HAHN: Yes, and that's where the origin quest started.

JAD: This is Beatrice Hahn.

BEATRICE HAHN: I'm a professor of medicine and microbiology at the University of Pennsylvania.

JAD: And so after they found it in macaques, what happened?

BEATRICE HAHN: It took a couple of years ...

JAD: But eventually, she says, they found SIV ...

BEATRICE HAHN: In still another primate species, the sooty mangabey.

JAD: And then in a few more.

BEATRICE HAHN: The African green monkeys, mandrills.

JAD: Pretty soon, it was all over the place.

BEATRICE HAHN: There are now I think 40 different species of African monkeys known to have their own version of SIV.

JAD: So then the question was, which one of these monkeys or primates passed it to us?

BEATRICE HAHN: Then, unexpectedly ...

JAD: A researcher named Martine ...

BEATRICE HAHN: Martine Peters.

DAVID QUAMMEN: At the center in Gabon.

JAD: Decided to test her chimps.

BEATRICE HAHN: Two orphan chimpanzees.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And bingo. She found a very, very close match.

BEATRICE HAHN: A virus that was the closest relative of HIV-1.

JAD: So ...

BEATRICE HAHN: Everybody said, "Well, you know ..."

DAVID QUAMMEN: It was a chimp.

ROBERT: It was a chimp. Okay.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Yeah, it came from a chimp.

BEATRICE HAHN: Yes.

JAD: But then the question was well, which chimps, or rather where?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Where, exactly?

JAD: So ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Beatrice Hahn and her colleagues started looking at chimps that came from different parts of Western Central Africa.

JAD: Now, getting blood samples from chimps in the wild is pretty much ...

BEATRICE HAHN: It just isn't feasible.

JAD: You know, because in the wild they hide the moment they see us.

BEATRICE HAHN: So you get stuck with fecal samples.

CARL ZIMMER: Poop.

BEATRICE HAHN: Yes, poop.

CARL ZIMMER: There's lots of DNA in there.

JAD: And viruses.

CARL ZIMMER: So they would just go to where the chimpanzees would sleep at night, and they would just, you know, collect some poop.

JAD: Bring it back to the lab, and Beatrice would analyze all the viruses.

BEATRICE HAHN: Over 90 different wild communities.

JAD: From every part of central Africa.

BEATRICE HAHN: Over 7,000 different fecal samples.

JAD: And slowly, they were able to piece together ...

BEATRICE HAHN: Which communities were infected and which ones had the closest to HIV-1. That's when it hit us for the first time.

JAD: What exactly hit you?

BEATRICE HAHN: The geographic origin of these chimps.

JAD: In 2006, her and her colleagues published that the human AIDS virus comes from a group of chimps, a very specific group that live in a very specific place.

DAVID QUAMMEN: This little corner of southeastern Cameroon.

BEATRICE HAHN: Between the Boumba River, the Ngoko River and the Sangha River.

JAD: These chimps were essentially penned in between these three rivers.

DAVID QUAMMEN: It's an area probably only of a hundred square miles. Not much more than that.

ROBERT: So when we're looking at what humans have and we're looking at what all of those chimps in Africa have, the most perfect match is this little territory up there in Cameroon?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Yeah.

BEATRICE HAHN: There is no other virus that is any closer. So that's that.

JAD: So can you reconstruct the spillover and the who that it spilled over into, as best—you know, as best as we understand it?

DAVID QUAMMEN: You can hypothesize. And the best hypothesis is the cut hunter hypothesis.

JAD: The cut hunter?

ROBERT: The C-U-T hunter?

DAVID QUAMMEN: That's right. A hunter who gets cut.

JAD: And what can we say about this guy? I mean, is he—what do we know about him?

DAVID QUAMMEN: If we had to guess? If we had to guess, that human was probably a Bantu man living very near the forest or in the forest in southeastern Cameroon. He was hunting. Maybe he had a bow and arrow, maybe he had a spear, and he kills a chimpanzee. Bingo here's a big pile of meat. And he starts to butcher it. He's cutting open the chest cavity. He's pulling out organs and he cuts himself. And he gets blood-to-blood contact. Chimpanzee blood against his blood. What happens is that the virus in the chimpanzee blood found itself in an environment that was unexpected, that was alien to it, but was not too much different from the biochemical environment it had been in, chimpanzee blood. It could function. And that's the moment. That's the moment it begins. That human is patient zero.

JAD: But why then? Why 1908? I mean presumably, people have been hunting chimps for a really long time. Why wouldn't this guy be patient seven million?

DAVID QUAMMEN: That's another of the big questions. People certainly in central Africa have been eating monkeys for thousands of years.

JAD: I mean, David says there's really no way to know, but this could have just been the right virus.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Maybe this particular virus evolved in a way that made it more transmissible in humans.

JAD: Or maybe it just got lucky to come along at precisely the right time.

CARL ZIMMER: What you're looking at ...

JAD: This is Carl again.

CARL ZIMMER: ... is a time when this part of Africa was being heavily colonized. The French and the Belgians were building train systems. And populations were on the move. Kinshasa, which was then Leopoldville, it was exploding. It was huge.

DAVID QUAMMEN: The cities were attracting people from the boonies in those days ...

JAD: So by 1908, all the virus has to do is get from that tiny village where the cut hunter lived to one of the new cities.

DAVID QUAMMEN: That happens almost certainly by river. I was stirred by the work of Beatrice Hahn and Mike Worobey to see what this scenario looked like on the ground. So I went to southeastern Cameroon and I chartered a little boat, about a 30-foot wooden boat with an outboard motor.

JAD: And he traced the path of the virus.

DAVID QUAMMEN: We went down the Ngoko River, and we stopped at a few villages. There are a couple little villages there, one of which has a market where you can buy monkey meat and crocodile meat.

JAD: And he says it wasn't hard to imagine how it all might have went down. Perhaps the cut hunter gave the virus to a woman who then passed it on to a fisherman.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Fellow that I called the voyager.

JAD: Who then got in the boat as David did and carried it down the river.

DAVID QUAMMEN: The Sangha River, which is—the Ngoko is a tributary of the Sangha. The Sangha becomes a bigger river 200 meters wide, which then flows to the Congo River, the big river.

JAD: And into the city.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And I imagined him sliding into Brazzaville around 1920. The first HIV-positive man to arrive in an urban center, where there's a much greater density of humans, where there are prostitutes, a greater fluidity of social and sexual interactions. And that seems to have been the place from which the disease went global.

ROBERT: So that's how it happened?

JAD: We could take it back even farther, actually.

ROBERT: What do you mean?

JAD: Because if you want to make a movie about the start of it, well, this is not the start. Because we got it from chimps, right?

ROBERT: Right.

JAD: So you could ask, "Who was chimp zero? What do we know about chimp zero," right?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Yeah. I mean, everything comes from somewhere. And again, by molecular work scientists have been able to determine that the chimp virus is actually ...

JAD: It actually comes from ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Two monkey viruses.

JAD: Two different monkeys from two completely different species.

ROBERT: What? Would they have encountered each other somewhere? Had a fight?

DAVID QUAMMEN: They probably encountered each other in the stomach of a chimp.

ROBERT: Meaning what?

NATHAN WOLFE: Well, from the perspective of a chimpanzee, monkeys they look tasty.

JAD: This is Nathan Wolfe.

NATHAN WOLFE: Professor in human biology at Stanford University.

JAD: And he says to fully understand this part of the patient—or rather chimp zero narrative, you have to grasp how it is that chimps hunt. And this is something he witnessed.

NATHAN WOLFE: In the Kibale National Forest in—in southwestern Uganda.

JAD: He described to us watching three male chimps converge on a tree full of colobus monkeys, which are these very small black and white monkeys.

NATHAN WOLFE: And one individual managed to grab two juveniles, and then the three individuals all met up and ...

JAD: Began to eat the monkey while it was still alive.

NATHAN WOLFE: The chimpanzee was going after an organ, you know, that—that obviously was a tasty morsel that he was going after. And—and the monkey was screaming bloody murder.

JAD: It is quite disturbing to watch, he says.

NATHAN WOLFE: But one of the things that struck me at that moment, was the depth of contact between the blood and body fluids of this monkey and the chimpanzee.

JAD: The chimps are literally covered in blood. They have blood on their face, in their eyes. And from the virus's perspective, this is spillover heaven. Okay, so the following is the closest that we can get to a zero point in this entire narrative. We don't know where it happened.

NATHAN WOLFE: And we don't know exactly the time. Say, some hundreds of thousands of years ago.

JAD: From the molecular clock, we know it was less than a million years. That's all we know. But whenever it was, chimp zero was hunting and it comes upon a monkey called a red-capped mangabey.

NATHAN WOLFE: The red-capped mangabey. This is a larger primate.

JAD: And these are tree-dwelling little—little guys?

NATHAN WOLFE: Tree-dwelling.

JAD: Little bit of red fur on their heads.

NATHAN WOLFE: Yes.

JAD: Chimp zero spots one of these monkeys, eats it. And in the process, he catches a red-capped mangabey version of the AIDS virus. Next, sometime after that first kill, weeks, months, we don't know maybe it was the same day, chimp zero comes across another monkey. And this monkey was called a spot-nosed guenon.

NATHAN WOLFE: Yes.

JAD: It's got a spot on its nose, I assume.

NATHAN WOLFE: There you go.

JAD: Very small.

NATHAN WOLFE: One of the tiniest monkeys of all of the old world monkeys.

JAD: And chimp zero eats that monkey and gets a spot-nosed guenon version of the AIDS virus, or the SIV virus inside it.

NATHAN WOLFE: So you've got the red-capped mangabey and you've got the spot-nosed guenons. You've got a guenon and a mangabey.

JAD: Two completely different kinds of SIV viruses inside the same chimp. Now under normal circumstances, according to Nathan, both of these SIV viruses would go nowhere because ...

NATHAN WOLFE: When one of these viruses makes the jump ...

JAD: They go from a place they've adapted to and that they know to a completely foreign landscape.

NATHAN WOLFE: Like a human being dropped off on Mars, maybe without a spacesuit. I mean, they basically are entering a completely alien habitat. The cells don't look the same. The environment is different.

JAD: And the chimp's immune system would normally kill them.

NATHAN WOLFE: But then once in a blue moon ...

JAD: Something crazy happens. These two viruses will end up inside the same cell in the same chimp at the same time.

NATHAN WOLFE: Literally, there is a single cell simultaneously infected with both viruses.

JAD: So suppose on one side of the cell, you've got the mangabey virus, and on the other side of the same cell you've got the spot-nosed guenon virus.

NATHAN WOLFE: And what happens is literally ...

JAD: Inside the cell ...

NATHAN WOLFE: ... you have an enzyme. It's called the polymerase enzyme. It's copying genetic information of the viruses.

JAD: This is what viruses do. They hijack these enzymes to make copies of themselves. Now here's the problem.

NATHAN WOLFE: These—these enzymes, they're not necessarily that sticky.

JAD: And while they're in the process of copying one virus, every once in a while they'll accidentally fall off mid-copy and go thwack!

NATHAN WOLFE: And latch on ...

JAD: ... to the second virus, and just keep on copying. And so what it ends up spitting out is a hybrid. Like that. Now this new mosaic probably won't go anywhere, because 99.999999 percent of the time when these hybrids happen ...

NATHAN WOLFE: It's a dead end.

JAD: The chimp's immune system is pretty sophisticated. It has evolved defenses against these viruses, and it will destroy them. But again, once in a blue moon ...

NATHAN WOLFE: So this is a blue moon after a blue moon after a blue moon to really get this. Finally, you get one particular mosaic virus between the mangabey and the guenon.

JAD: That through sheer random luck, works. It landed on the exact right combination of genes that allowed it to evade the chimp's immune system.

NATHAN WOLFE: I mean, one of the amazing things to think about is how many—how many hopeful monsters you had to have in order to get that one that actually survived.

JAD: Probably trillions. But then ...

NATHAN WOLFE: Boom.

JAD: Suddenly in a flash, from these two viruses that can barely survive in the chimp, you get a new virus.

NATHAN WOLFE: A little bit mangabey, a little bit guenon.

JAD: That can not only survive in the chimp, but can thrive. In fact, for this baby virus, the chimp is the perfect host.

NATHAN WOLFE: And that was the virus that ended up spreading, jumping over to humans, and has been this massive and incredibly dramatic sort of tear in the fabric of humanity.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Let me add another parentheses. There are essentially 12 major groups of the HIV virus.

JAD: What David means is that 12 different kinds of HIV viruses have spilled over 12 different times.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Eight of them came from monkeys, three of them came from chimps and one came from gorillas.

JAD: Wow.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And of those 12, only one of them is responsible for the global pandemic.

JAD: There are 12 kinds!

DAVID QUAMMEN: 12 times that we know about. It's probably happened dozens and dozens more times that we don't know about. So the spillover is not a highly improbable event.

NATHAN WOLFE: These sorts of viruses, they're constantly pinging at us. They're pinging it us and pinging it us. We see it happening all the time.

JAD: You see it happening?

NATHAN WOLFE: All the time.

JAD: Nathan has set up a series of monitoring stations.

NATHAN WOLFE: In places like central Africa.

JAD: And he and his colleagues have been tracking what he calls the viral chatter in the people who hunt these primates.

NATHAN WOLFE: We collected specimens from the animals that they were hunting.

JAD: They compared that to blood samples from the hunters themselves.

NATHAN WOLFE: And guess what? We found a whole range of new retro viruses that were moving over into these hunters.

JAD: For example, he's been tracking something called the Simian foamy virus, which is ...

NATHAN WOLFE: From the same family as HIV.

JAD: And he has seen it hop from an individual gorilla to an individual human who killed that gorilla.

NATHAN WOLFE: Yeah. These are almost certainly what we call primary transmission events.

JAD: Oh, so you really are looking at the potential beginning of something, but who knows what?

NATHAN WOLFE: Yes. So if you want a patient zero, really clear patient zero, it's some of these individuals that have been infected with these viruses. And the real question is, how do we stop patient zeros? How do we avoid patient ...

JAD: Patient one and patient two.

NATHAN WOLFE: Exactly.

JAD: So Nathan is developing a series of tools, like ...

NATHAN WOLFE: Digital surveillance. I mean, some of these places—I work in some places in Democratic Republic of Congo, you basically have to fly in to get there.

JAD: No roads. Often no electricity. But ...

NATHAN WOLFE: Many of these places, they still have cellphone towers.

JAD: So Nathan has begun to track cellphone call patterns in these communities. So if he sees a blip of many calls to a medical center within a short period of time?

NATHAN WOLFE: Okay, boom! Now we got to investigate that. We continue to find viruses that are completely novel, and we're looking to determine if these are—if these are the next HIV.

JAD: Because think about it he says, HIV landed in humans in 1908, but we didn't know about it until 1981.

NATHAN WOLFE: We had decades of time when this was a virus before it spread globally.

JAD: What if we'd been looking for it?

JAD: A lot of people to thank for this segment. Thanks to Nathan Wolfe.

ROBERT: For being Nathan.

JAD: And he has an awesome new book called The Viral Storm.

ROBERT: Also, thank you to Carl Zimmer, whose book on viruses is called A Planet of Viruses. And thank you also to him and to Michael Worobey. Their interview was recorded on a podcast from Meet the Scientists, which you can find at microworld.org.

JAD: And thanks to David Quammen who's got a book called Spillover coming out very soon, which is all about diseases crossing over from animals to us.

ROBERT: And also to Beatrice Hahn at the University of Pennsylvania.

JAD: And to Katie Slocum from the University of York for letting us use her recordings of chimpanzees.

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.