Apr 2, 2012

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Okay, ready? Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. And this whole hour we have been talking about—go ahead.

ROBERT: Guts.

JAD: Guts.

ROBERT: In the last section, we talked about bacteria, and the armies of them that are in your gut.

JAD: Yeah. The problem is that they're a little hard to picture. They're kind of abstract.

ROBERT: Why don't we finish with a story that makes the whole issue real and much more concrete? This is the tale of a troubled relationship between a man ...

JAD: And his on-again, off-again gut.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: Hello.

ROBERT: Hello.

JON REINER: Hello.

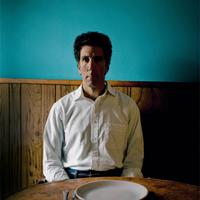

JAD: The man's name is Jon Reiner. He's a writer. Lives here in New York.

JON REINER: Mm-hmm.

ROBERT: So one day you are eating your way through your life as you usually do, and then things take an odd turn.

JAD: Yeah, how did it begin?

JON REINER: It began with a surprise. I was at home, and I was about to go make myself a tuna fish sandwich.

JAD: Jon thought, "You know what? Let me go to the bathroom first. Get that out of the way." So he sits down on the pot to do his business ...

JON REINER: And I felt a funny twinge in my gut.

JAD: Now Jon has had gut pain before.

JON REINER: I suffer from something called Crohn's disease, which is a gastrointestinal condition. But I had gone through a period of about a year's remission. Excellent health.

JAD: And so when this pain came on, Jon figured, no big deal.

JON REINER: It seemed to come out of nowhere, and I thought it'll go away out of nowhere.

JAD: Like usual.

JON REINER: But it didn't. Within about a minute, what was a small twinge all of a sudden felt like a knife into my gut.

JAD: Before long ...

JON REINER: I'm on my living room floor flat on my back, and I can't move.

JAD: Jon calls an ambulance. They rush him to the hospital, and when they get there, the doctors take one look and tell him, "Your intestines were clogged, and now they've burst."

JON REINER: And it's now spreading bacteria throughout your system. Basically, you're on the verge of having sepsis.

JAD: Meaning you could die.

JON REINER: So you need emergency surgery, but ...

JAD: They also told him ...

JON REINER: ... that I should recover.

JAD: And when he came out of the OR, it looked like he would. But the doctor said, "Let's play it safe. Stay here for a week. We'll feed you through an IV and give your gut a break."

JON REINER: So I'm on an IV for a couple of days. And I've been on nothing by mouth in the hospital numerous times before, but always for four to five days.

JAD: And after four or five days, Jon says, what normally happens is that you'll start to feel hungry again.

JON REINER: And that's a great sign. That means that your gut is healing, and ...

JAD: It's ready for food. But this time, that didn't happen. In fact, he says, he got sicker.

JON REINER: Nausea, vomiting, chills, fever spike.

JAD: So the doctors take more pictures of Jon's insides, and they noticed something weird.

JON REINER: In the area where I had a tear in my intestine, there's now a fistula, which is a hole.

JAD: Now normally, this is something you could sew right back up. But the doctors tell him, "In your case ..."

JON REINER: "No. The tissue around the area of the tear is so compromised that you can't withstand another surgery right now. Plus you've got a high level of infection again. You're no candidate for surgery."

JAD: "Our only solution," they tell them, "is to let your gut heal on its own. But In order to do that, we've got to shut it down."

JON REINER: Yes.

JAD: Basically, numb it with anesthesia.

JON REINER: So my gut was in an induced coma. Nothing would pass through it, there'd be no activity.

JAD: Which meant, the doctors told him, obviously no eating. Instead ...

JON REINER: "We're gonna put you on a food pump." And the food pump is a mechanical pump about the size and the weight of two bricks carried in a backpack.

JAD: And the pump in the backpack is attached to this big bag.

JON REINER: Big bladder. The big 3,000-milliliter bag of TPN is the medical name for the nutrients.

JAD: What does that stand for?

JON REINER: Total parenteral nutrition. And a stream runs out of the pump through the tube into my arm.

ROBERT: You were going to be given essentially an outdoor stomach.

JON REINER: That's right.

JAD: And this is where our story really begins. So Jon goes home with his new exo-stomach. He can't eat, but every day around mealtime, he says, he would turn on the food pump. And this is actually what it sounds like.

[whirring noise]

JON REINER: So I'd start my feeding at four o'clock. The pump would start, I'd sit on the loveseat for a while. My kids would come home from school. My wife would come home from teaching, and then the real food would come into the apartment.

JAD: Sometimes neighbors brought food over. Sometimes Jon's wife would cook. But regardless ...

JON REINER: I was always sitting on the loveseat in our living room with the food pump whirring.

JAD: Like a dishwasher.

JON REINER: Mm-hmm.

JAD: While just a few feet away, his family would sit at the table.

JON REINER: Eating fabulous food.

JAD: Night after night this happens.

JON REINER: And it's making me absolutely crazy.

JAD: And he says after about a week of this, and then two weeks, and then three weeks of just sitting there night after night watching his family eat dinner without him, he says he would start to drift off and get lost in these really vivid daydreams of meals that he'd eaten in the past.

JON REINER: One of the first memories I have is going to Katz's for the first time.

JAD: Katz's is a famous Jewish deli in Manhattan.

JON REINER: And standing there at the counter where the counterman cuts the pastrami and he puts it on a plate. And he gets it out of the hot cooker and it's on a fork, and he hands it to you and you take a taste.

JAD: And he says in that particular instance when he took a bite, that first bite of the pastrami sandwich, it was like pow! He said it was the first time in his life where suddenly he was like, "Oh my God, I'm Jewish! I am Jewish!"

JON REINER: These are my people.

JAD: And that was the first time you felt that?

JON REINER: It was. It was.

JAD: And after about a month of no food at all and these vivid daydreams about food something weird happened: Jon got hungry. Like, actually hungry. Which really doesn't make much sense because hunger signals normally travel from the gut up to the brain, and his gut was numb. But he says he really started to feel hungry.

JON REINER: It was, you know, I think of it, it was an existential hunger.

JAD: And it got really bad. For example ...

JON REINER: My wife's a terrific cook, and one night she made a little treat for the kids: mini burgers, and French fries, and our small apartment smelled like the kitchen of a White Castle. So my wife brought out this big plate of sliders in a pyramid and the kids were knocking down the pyramid and throwing them back. And I couldn't take it anymore, so I snuck out of the living room while they were preoccupied. I went into our kitchen, and there were some fries on the stove top. And I put my hand on the fries and I brought them up to my mouth, and I was expecting salt and oil.

JAD: Fatty goodness.

JON REINER: Fatty goodness and the texture of crunchiness and all that.

JAD: Mmm. I'm tasting it now.

JON REINER: And I put it on my tongue and I've got nothing.

JAD: Nothing?

ROBERT: Really?

JON REINER: And I'm rolling it around.

ROBERT: You can't even feel it on your tongue?

JAD: Not even the salt?

JON REINER: I mean, my tongue feels—it's like when you go to the dentist and you've got Novocaine. And my tongue is numb, and so I start ...

JAD: What was going on? Was it your tongue was just out of practice?

JON REINER: I couldn't figure out what was going on. And then I brought up a knife.

JAD: And Jon claims that when he looked at the reflection of his tongue in this metal knife ...

JON REINER: I see that my tongue is as flat and smooth as this Formica tabletop I've got my hand on in your studio.

JAD: Oh, so you don't have the little bristly, funny things?

JON REINER: No bristles. Right. And I realize I haven't used it in so long that my taste buds have evaporated. They're gone. And at the moment that that happens my oldest son, Teddy, who was nine at the time comes in and he says, "Dad, you're not supposed to eat." I said to him, "I wasn't eating. I wasn't eating!"

JAD: It's like you switched places, almost.

JON REINER: And he looked at me with the most scornful, disgusted, just ashamed expression. And I was completely humiliated. I had not only failed as an eater ...

ROBERT: Like a shame flood.

JON REINER: Right. I'd failed as a father as well.

JAD: As the weeks dragged on and Jon didn't get any better, he actually started to take that thought seriously. Like, maybe he really was failing at being a dad.

JON REINER: I'm a stay-at-home dad. And as a result, I'm the shopper and the cooker and the food planner and the provider for us. And I was out of commission. Three years out of work.

JAD: With no gut. Meanwhile ...

JON REINER: I can't stop thinking about food. I'm remembering food that I ate 20 years ago like I had it that afternoon. And I'm online looking up menus from restaurants that I've gone to.

ROBERT: Really?

JON REINER: Yeah. And looking up recipes for dishes that I've made.

JAD: And this obsession grew and grew until one night, he says, his neighbor Marsha ...

JON REINER: Decided to cook for us one night when I wasn't eating, and she brought down a chocolate bundt cake for my wife and kids to eat.

JAD: Walks it right past Jon on the way to the kitchen.

JON REINER: And I could smell this thing. I could smell the rum. I could smell the eggs. I could smell the flour. I could smell everything.

JAD: So again, he sneaks into the kitchen.

JON REINER: And I lower my nose down to this bundt cake, and I'm smelling it and I'm sniffing it and I'm inhaling this thing like an anteater. And that's not enough in my state, so I plunged my hands into the chocolate cake.

JAD: You what? [laughs]

JON REINER: I plunged my hands into the chocolate cake.

ROBERT: In order to get one with the goo or what?

JON REINER: In order to get some sensation of connection with food.

ROBERT: Did you think, "What's happening to me?" Or did you think, "Oh, the joy!"

JON REINER: At the moment my fingers were in this cake, I felt, I'm in heaven. I've reconnected with the living. I have food, if not in me, at least on me. And at the moment while I'm experiencing most pleasure, my wife comes into the kitchen.

SUSAN REINER: When I went in to get the kids some more food, I found him.

JAD: This, of course, is Jon's wife, Susan.

SUSAN REINER: With his hands in the cake, just trying to touch the crumbs. And he looked so guilty. I was like, "What are you doing?"

JON REINER: "What are you doing?"

SUSAN REINER: Like somebody's going through an underwear drawer. It was very wrong.

JON REINER: And I have no explanation. I mean, I can say, "I need to do this. You have no idea how wonderful this is. Please give me some time alone with my bundt cake."

ROBERT: [laughs]

SUSAN REINER: It was this bizarrely funny but deeply sad, perverse moment.

JAD: Yeah.

SUSAN REINER: I suppose that was the first crack in my bubbled attempt to pretend things were normal. You know, I realized how bad things had gotten.

JAD: And after that, she says, things only got worse.

SUSAN REINER: It just became there was never anything to be happy about. He wasn't able to eat. He wasn't sure what the prognosis was. He wasn't sure if he was going to need a second surgery. It was just all bad.

JAD: She says Jon became really depressed.

SUSAN REINER: And he became very difficult to even—not even to cheer up, but just to say, "Well, let's just not talk about it for now." You know, he was constantly expressing his unhappiness.

ROBERT: Was that the thing? It was dark all the time?

SUSAN REINER: Very dark. It just became very hard to face.

JAD: So she left.

SUSAN REINER: Well, I had spring break, and my kids had spring break.

JAD: So Susan took the kids to her parents' place in Indiana for a week.

SUSAN REINER: I needed—I needed to take a break.

JAD: Not for good. Maybe the kind of break that means, "I'm not really sure what our future looks like."

SUSAN REINER: I don't know how we're gonna do this.

JAD: "And I can't really figure that out while I'm with you."

JON REINER: So I was alone.

JAD: Not entirely.

JON REINER: Well, I was on the food pump, and not doing well.

JAD: But after a few days of moping around the house, Jon gets an idea.

JON REINER: What I need to get myself out of this is I need to return to a place of sanctuary for me. There was a restaurant not far from your studio here called Chanterelle. It's a French restaurant, and it was one of these very expensive capital-letter restaurants that my wife and I had always planned to go to if we had a special occasion. For years, I walked past this restaurant, and I would look in the window before getting onto the subway, and I would see the plates of scallops coming out, and the wine steward pouring red wine, and the handwritten menus on the tables and things like that. So I thought, "If I can get to Chanterelle, and if I can look through the window, then I can heal myself. I'll have a reason to hope."

JON REINER: So I got on the subway, and it was past four o'clock and I was supposed to be home starting up the pump and feeding. And I got off the subway, and I walked over to Chanterelle, and I was kind of a little dizzy and delirious. And I get to the window, and the dining room is empty. There's dust on the floor, the wall panels have been stripped, the tables are bare. It's empty. It's a cave. Sometime in the intervening months or the preceding months rather, Chanterelle has closed. And I didn't know that.

JAD: Oh, you're killing me with this story.

JON REINER: And I think to myself: "You've reached the end of the line. This is it. There's nowhere else to go." And I walked towards the river, and I know that people throw themselves in and they do this. And it never made sense to me before, you know? I wasn't ever ready to end things.

JAD: Were you having suicidal thoughts?

JON REINER: I was having really depressed thoughts, and I don't know that I would have thrown myself in, but it was the first time I was standing at the edge thinking about it. Thinking about this is how these things happen. So I got to the river and I blacked out, collapsed on the sidewalk. And I woke up and it was dark. I had scraped my chin and my elbows were bruised, and I'd taken a hard fall. And I got up and I started to walk around. I was on this buckled old sidewalk, and I looked around and there are these Federal-era houses. And there was a grill, a gas grill in one of the backyards that was going. Somebody was cooking dinner, and I could smell it. I could smell the smoke coming off the grill. And I could smell it was pork chops. And I was so delirious and so happy to be smelling food that I took it upon myself to finish cooking this guy's meal.

JAD: Wait, what? That's so eerie.

JON REINER: So I lifted up the lid. I lifted up the lid, and it looked like to me one side of the pork chops were cooked and they were ready to be flipped. So I flipped them.

JAD: [laughs]

JON REINER: And I was so far gone that I thought, "Okay. Well, four more minutes and these babies are gonna be ready to go." And I didn't have a watch, so I started counting down four minutes in my head because I was gonna get this stuff perfect. And all of a sudden, the back door of this townhouse opens up and a guy walks out with an apron on and a cocktail in one hand and a season shaker in the other. And he looks at me, and I look very borderline. I mean, I'm rail thin, I'm cut up from having fallen on the sidewalk, I've got a crazy expression in my eyes, I haven't shaved in a week. I look really very unsavory. So he sees me, and I have no way of explaining myself other than to say, "They're just about done." And I hand him the tools, and I turn around and I walk away before he has the chance to call the police or anything like that.

ROBERT: How many years ago was this?

JON REINER: This was now three years ago.

JAD: And what do you take away from that? Was that some turning point where you walk away from the grill and you're ready to fight the good fight or what?

JON REINER: That only happens in the movies and in fairy tales. What actually happened was I got sick again. I had another infection, more bacteria, and I had to go back to the hospital. And when I went back to the hospital this time they said, "Okay, we can't even do the food pump anymore because you keep getting these infections. And if the bacteria spreads to your bloodstream through the food pump, then you'll be gone. And we can't operate on you because you won't survive the surgery. So all we have left is to try eating. The only thing that's left is to go back to food. Because you can't ingest it intravenously, we're afraid of infection, and we can't repair your gut surgically. So the only way you can keep yourself alive is to try to use your gut again."

ROBERT: So they start you on a round of—I don't know—baby food? Gerber?

JON REINER: I did start on the traditional applesauce and jello and pudding. soft and easily digested foods.

JAD: And Jon says it worked. His body was able to take the food.

JON REINER: But I couldn't taste anything. And it continued that way for another couple of months.

JAD: And did the food ever taste like food again?

JON REINER: Well, I was at the radiologist.

ROBERT: This is not the scene I was expecting.

JON REINER: Well, you know, I have a little ritual with this particular radiologist. He's on the East Side, and whenever I get tests there, when I'm done with the tests, I'm able to eat again. And again, this is when you do test prep, you're going about 24 hours without eating. So, you know, the thought of food becomes a celebration that you're gonna have, right? So there's a diner on Third Avenue and 84th Street, 85th Street that I always go to, and I get the same meal every time. I sit at the counter and I get fried egg and bacon sandwich on whole-wheat toast.

JON REINER: So I went there and I got the last seat at the counter, and I ordered my usual. And I chew into it and I realized that I've got sort of embryonic flavors going on. I've got the start of the sensation of tasting and the start of flavors in my mouth. And I could feel that great combination of the fried egg congealing with the crunchy bacon and the crunchy toast. And I do the same mirror—I've got a knife, a butter knife, and I do the same mirror-knife examination at the counter. And I can see that where before it was shiny and smooth as a porpoise, I've got little bristles. I've got little bumps on my tongue, and I can taste this fantastic $3 sandwich.

ROBERT: Do you kiss the lady sitting next to you?

JON REINER: Well, I turn to the guy sitting next to me and I tell him, "This is the best damn thing I've ever eaten." And In classic New York diner fashion, he looks at me, he looks up from his Kindle, he looks at me and he says, "You should try the meatloaf."

JAD: [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs]

JON REINER: And I think, "This is it. I'm back, baby. I'm back!"

JAD: Thanks, of course, to Jon Reiner whose book is called The Man Who Couldn't Eat. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Thanks for listening.

[ANSWERING MACHINE: Start of message.]

[JON REINER: This is Jon Reiner. Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad. Our staff includes Ellen Horne, Soren Wheeler, Pat Walters, Tim Howard, Brenna Farrell, Dylan Keefe, Lynn Levy, and Sean Cole, with help from Matt Kielty, Rachel James, Brennan MacMullen and Raphaella Bennin. Special thanks to Christian Luftsa, Clint Burger, Barry Jesse, Harold Bagnell and the Rutgers University Animal Care program. Thanks, guys.]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.