Jul 24, 2012

Ever wonder what's with all the goats? Like that one (I'm eying you, Guy) standing up over there, on top of these words (Don't eat these words, Guy, they're all I got.). Does Radiolab have some kind of goat fetish? Was Jad born in the year of the goat? Does the show have some seedy underground ties with the feta industry? Nope, it all goes back to the story "Goat on a Cow" from Detective Stories—one the first Radiolab episodes ever. And over the years, the image of a goat standing on top of a cow became a kind of mascot for the show, because it felt like a perfect symbol for what we’re trying to do—to make you to look twice. To follow your curiosity. To indulge the double-take.

If you haven’t heard “Goat on a Cow,” you should probably drop everything and listen right now.

OK?

OK.

But I'm not here to tell you what a great story it is. There’s more to it than that. This piece of radio was a turning point for the show—one that, I think, is interesting for anyone struggling with a creative puzzle, and trying to do something ambitious and risky and new. So, if you're interested in how one goat on one cow… seen by one teacher of one sister of one reporter… changed the course of our little radio show, read on. And if not, peace unto your Tuesday.

Photo by sLENGfJES flickr/CC-BY-2.0

“Goat on a Cow” was a hard story to produce. Really hard.

The piece itself almost got cut. "I don't know if Laura ever knew how close to we were to killing that story," says Ellen Horne (now Executive Producer, then questionable future, funding-seeking, very-much lowercase p, producer of Radiolab). This was back in 2005, and the Laura in question was Laura Starecheski, reporter of the piece. They had gone back and forth on about 30 drafts--all on paper. They had pages and pages of transcripts of the audio Laura had collected. Binder after binder of attempts at written narration. Epic scripts with blacked-out sections and extensive notes.

The problem they were circling around was that they couldn't quite figure out what the piece was about. They knew it was about a woman, Ella Chase, who seemed unknowable in some way. They knew it was about a growing mob of people—a teacher, students, now Laura herself—who were interested in the act of finding meaning in that unknowable woman’s life. Originally the piece was slated to be part of a show on "Empathy." It would be paired along side a scientific study about mirror neurons, and illustrate the point that we only ever know another person through ourselves. Dreamy. Cool. Science-y. But... lacking the real feelings and drive—that emotional meat—that makes a story snap into place.

So. They did all the dutiful things you do when a piece lacks emotional meat. You try to gussy it up with good writing. You throw in literary references. Laura remembers at one point they wrote in an allusion to the Odyssey. How Odysseus tried to hug the soul of his mother when he found her in the underworld, but could not grasp her. She turned into a cloud of air.*

Eventually, they got a final draft together. And when it came time for Laura to hear it, she took a deep breath and listened. Her honest reaction: "It was... OK."

Jad and Ellen, meanwhile, were having the same reaction. They were in Ellen's pink Geo Prizm on the way down to DC.** After sitting for a few minutes in the stagnant cloud of their “eh,” they pulled out Laura’s raw interview tape. With nothing else to do—traffic was bad, and only getting worse—they began to quietly listen. As though perhaps in that raw footage, they’d uncover a lost clue. Some scene or forgotten character that would solve the piece. And thank goodness for I-95 on a weekday. Because by Delaware—though they hadn’t made it many miles—they had listened through all five hours of tape, and had come to the same startling realization: the key to the story wasn’t some new scene or tangent, it was Laura. Real-life Laura!

See, the Laura that was narrating the piece after-the-fact in the studio sounded, as Ellen put it, "awkward and stressed-out."

"Ha ha," says Laura, hearing this now. She remembers feeling stiff in the studio. At the time she was new to radio. “I knew I didn't have the power to emote. It's really hard. Even for a pro. You're never going to get the same feeling."

But the Laura hiding in the interview tape was bursting with feeling. Alive and light on her feet. Some parts nervous, some parts cheerful, always curious. “Delightful,” Ellen recalls.

Laura’s not alone here. The studio poses an odd set of conditions. You're all by yourself. In a vacuum. Far away from the people you interviewed, sealed off in a soundproof room. Knowing this could end up on National… Public… Radio. It’s not just a performance problem, it’s an existential one. Who are you? Are you "in" the story? You’ve talked to these people, you’ve entered their lives. Are you a part the action now, or can you maintain a stance as an outside observer? Are you an expert? An instigator? A removed, formidable Cronkite tour guide? Is it enough to be a weirdo who got curious enough to bring a microphone along? Is it your job to hide that maybe that’s all you are?

No.

That was the answer Jad and Ellen came to in the pink Geo Prizm. In that hot, trafficy car, the Laura coming through on the raw tape was pure refreshment.

And they wanted to do everything they could to harness that voice. So they pulled over to a Mexican restaurant on Rte 1. And without any of those binders or folders—no transcripts, no worked-over scripts, no shackles of past work—they made a map of scenes they liked, along with a bunch of questions they had for Laura. Number one: WHY was she making the piece?

When they returned to New York, they got Laura in the studio and asked her why the heck she was so obsessed with tracking down the story behind this random box of letters.

She paused for a second. Then, with a bit of embarrassment, said:

My— my mom kind of, uh…. fostered that. Like when we were little, one of our, uh… outings… ha ha… that we would do would be to go to this toxic dump near our house where we grew up.

You can hear the freshness in her voice. That she’s really thinking about the answer. Stumbling into it for the first time.

They sealed off this mountain and made people move off it. So you’re walking along a trail and you see all these old abandoned houses. So we would go into the houses. We’d find pay stubs, dishes, paintings. We’d try and figure out—why?

She catches herself.

You can hear Jad begin to smile.

Like, even though we really knew why the people had left, we’d try and make up other stories about why they left…

By now Jad can’t hold it in anymore, he’s cracking up.

And this became the top of the “Goat on a Cow” story.

From there the conversation was easy. Laura retold the entire tale. When Jad had questions, he asked them. When she didn’t know the answer, she’d think about it. When he was surprised, a real “wow” would pop out.

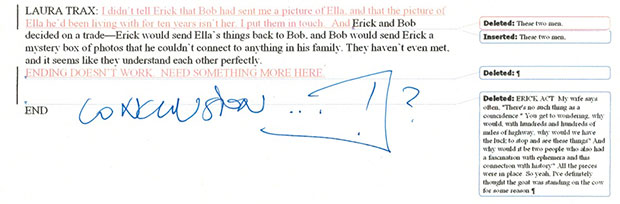

A snippet from one of the many drafts of 'Goat on a Cow'

And finally, that pesky ending. The overwritten, overwrought conclusion about how we may never know another person, complete with heavy music and references to ancient Greece… annihilated in three simple words.

The. Nonchalant. Cow.

They walked out of the studio and realized they had it. The narratorial backbone for the piece. After literally a year of sweating through drafts, the story revealed itself in about three hours of chatting.

Radiolab now relies heavily on this technique. They call it “the Braindump," where they head into the studio to record a raw conversation that guides the form of the story.

Ellen admits it’s a technique that might just have easily been used once…then let sail to the wind. Instead, this hard-won solution—a happy accident born of frustration—helped create the Radiolab “sound.” A sound that's sort of like a conversation—with every tangent rendered in full-Technicolor detail—with interjections (laughter or questions) that can bring you, mid-story, back to the main narrative train. It didn't sound like anything else on the radio, and, to be totally honest...it rubbed some listeners the wrong way. When Radiolab first went on the air, the hate mail often outweighed the fan mail: "Get these guys off the air," "Click n Clack on horrible geek speed," "PLEASE STOP THE ANNOYING SOUND EFFECTS!”

But something else was going on too. After “Goat on a Cow” aired, listener after listener wrote in to say how much they loved it. Illustrations appeared, along with photographs of goats spotted on cows and all sorts of funny things. Awards were received (from “Third Coast,” which is basically public radio’s Emmy Awards. I mean, you can catch producers wearing not only their fancy Converse, but their nice t-shirts—the ones without the coffee stains—to this thing!). And the team realized there was something special about this technique, not simply that it sounded fresh—an aesthetic novelty—but that it had the power to unlock truths and dramas and absurdities not always discoverable in the written word.

So what is “Goat on a Cow” really about?

Laura says in a way it did end up being about that initial question: can you ever really know someone? But it’s also about that feeling you get when you discover an old box of letters. The immediate desire to know more. “What IS that?” She asks. “That basic urgency?”

Perhaps a heady question, but as you ride along with Laura—knocking on doors, leaving telephone messages for strangers; as you feel the nervous thrill of getting a door slammed in your face, and the lonely echo of no response from inquiry letters; when you finally, at last, get that call back from the almost-forgotten Bob—you understand it. Because standing there alongside Laura, with the sting of that door slam still on your nose, you’ve felt it too. “It’s the desperation to get close to people,” Laura says.

Laura said that what that recorded conversation in the studio really did--more than just calming her nerves or getting her to sound loose--was to give her “permission” to enter the story. Once she had that, everything changed. The matter at hand—that mess of tape to sort—changed from assignment to quest.

Moo, my friends. May your summers be full of eight-hoofed double-takes. And doors slammed in pursuit of connection. Because at least a slam implies attempt. Which is better than no attempt. Which is a sad ball. On the floor.

Time to stop blogging. See you next week. Stay nonchalant in this heat.

News from Laura Starecheski, now a staff producer for the wonderful new show State of The Re:Union. She recently won an award for a story from SOTRU's Wyoming episode, "Laramie After Matthew Shepard.”

*From the Robert Fitzgerald translation of Homer’s The Odyssey:

I bit my lip,

rising perplexed, with longing to embrace her,

and tried three times, putting my arms around her,

but she went sifting through my hands, impalpable

as shadows are, and wavering like a dream.

**Jad and Ellen were on their way down to DC that trafficy day in the Geo Prizm, to meet with NPR’s science desk about this quirky little show they were cooking up, called Radiolab…