Feb 5, 2013

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Ready?

ROBERT KRULWICH: Mm-hmm.

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab and ...

ROBERT: Speed is our subject.

JAD: [laughs] You beat me to it.

ROBERT: I ...

JAD: Actually, that's what this whole next segment is about.

ROBERT: See, I had it in my bones.

JAD: Just to set it up. I got this idea from my friend Andrew Zolli, who is a fantastic writer, wrote the book Resilience: Why Things Bounce Back. We were at a diner. I was telling him about this show, and he says, "You should do something about the stock market." And I was like, "I'm the last person who should do something about the stock market." He's like, "No, no, no, no. Forget everything you think you know about the stock market."

ANDREW ZOLLI: Most of us, when we think about stock markets, if you just close your eyes and you think about the financial world, what you imagine is a bunch of people in a room, and they're all wearing funny-colored jackets, and they're shouting at each other.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, stockbrokers: And these two bid, two bids. Two.]

ANDREW ZOLLI: Waving bids up.

JAD: Waving, yeah.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, stockbrokers: 70 bid.]

ANDREW ZOLLI: This kind of raucous ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, stockbrokers: 23!]

ANDREW ZOLLI: ... people screaming, trying to figure out what a price is. And we have this sort of iconography, this cultural iconography of how the financial system works that is, in large part, completely divorced from reality.

JAD: Because he told me—here's my first surprise—that somewhere between 50 and ...

ANDREW ZOLLI: 70-plus percent ...

JAD: Of all the trades that happen on what we think of as Wall Street ...

ANDREW ZOLLI: Are not executed by a human being as the result of a human decision. They're actually executed by an algorithm at a speed, rate and scale that is beyond our comprehension.

JAD: So I decided I would try and comprehend this new world that he was describing. And since this is a subject matter that generally makes me frightened, frankly, I decided to call up David Kestenbaum from Planet Money.

DAVID KESTENBAUM: Hey, Jad?

JAD: Hello.

ROBERT: The David Kestenbaum.

JAD: Indeed.

DAVID KESTENBAUM: There could be more than one.

JAD: There probably are on Twitter.

JAD: In any case, it did not click for either of us just how fast, how inhumanly fast trading had gotten until we visited this firm called Tradeworx.

DAVID KESTENBAUM: Hey. David.

MIKE BELLER: Nice to meet you, David.

DAVID KESTENBAUM: So we go into this little building in New Jersey. It looks like it's a startup or something, and this guy says, "Hello."

MIKE BELLER: My name is Mike Beller. I'm the chief technology officer of Tradeworx.

JAD: And Mike sat us down at this computer, opened up this little program that logs ...

DAVID KESTENBAUM: Exactly what is going on at the market at insanely specific times.

MIKE BELLER: You could pick a stock. We could look at Yahoo, for example. We can literally pick some time of day that we're interested in.

DAVID KESTENBAUM: What time is this? Wait, so what time?

MIKE BELLER: So this is at 11:35 and 26.979 seconds.

JAD: Really!

MIKE BELLER: And in fact, that's not enough precision for us because we really deal in microseconds.

JAD: That would be millionths of a second.

MIKE BELLER: So we have another way of measuring time, which is the number of microseconds since midnight of the previous day.

JAD: Can you read that 417 number?

MIKE BELLER: Sure. 41,729,979,559 microseconds since midnight.

JAD: Wow!

DAVID KESTENBAUM: So—so do you always have lunch at like 2,000,305,000?

MIKE BELLER: No, that'd be really early.

JAD: [laughs] How many trades do you do in a day?

MIKE BELLER: I think it depends. A lot. A high-frequency trader might do 1,000 trades in a minute.

[Very fast pulses]

DAVID KESTENBAUM: It's about that tempo.

MIKE BELLER: But it's kind of very burst-y.

JAD: Now what happens during those bursts is a bit of a mystery.

ANDREW ZOLLI: It's very hard to see what's going on.

JAD: Often, says Andrew, it's the computers testing the market.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Testing to see if they can find a nibble on the other side.

JAD: They'll fire out a bunch of buy and sell orders, and then when another computer bites on one, they'll quickly cancel the ones that didn't stick.

ANDREW ZOLLI: "Nope, sorry, didn't want to do that."

JAD: And they're doing this on a microsecond basis. "Buy."

ANDREW ZOLLI: "Nope, sorry."

JAD: "Sell."

ANDREW ZOLLI: "Nope."

JAD: "Buy."

ANDREW ZOLLI: "Nope."

JAD: "Sell again."

ANDREW ZOLLI: "Nope, forget about that."

JAD: "Buy."

JAD: "Nah."

ANDREW ZOLLI: And they create huge volumes of transactions that just disappear into the ether.

JAD: There are some computer algorithms, he says, whose whole job is to ...

ANDREW ZOLLI: Combat other algorithms.

JAD: Fake them out.

ERIC HUNSADER: For example, we just had a very good example. It happened about a month ago, in Kraft.

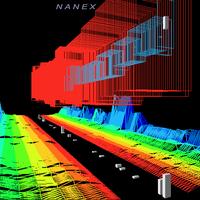

JAD: That's Eric Hunsader. He tracks high-frequency trading for the firm Nanex.

JAD: Kraft, like Kraft cheese, Kraft?

ERIC HUNSADER: Yes.

JAD: He says what they saw was this algorithm jump into the market, buy up a bunch of Kraft, which ...

ERIC HUNSADER: Jammed the price up.

JAD: Which allowed that algorithm ...

ERIC HUNSADER: To sell at much higher prices to the other algorithms. And we calculated it out, it cost them $200,000 to push the price up, but they were able to sell about $900,000 of stock, netting a gain of over half a million dollars ...

JAD: In a matter of seconds. Now to put that in context, back in the day, you know, 20 years ago when the humans still ran the trading pits ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, stockbroker: 500!]

JAD: ... according to this guy ...

LARRY TABB: I'm Larry Tabb, founder and CEO of the Tabb Group.

JAD: ... the average time that it took to execute a trade was ...

LARRY TABB: Around 11 or 12 seconds back then.

JAD: And when you ask people, "How did we get from 11 or 12 seconds to ..."

MIKE BELLER: 41,729,979,559 microseconds since midnight.

JAD: ... phrases like that, the answer is kind of surprising. But I'll just start with the obvious part, at least the part that's obvious to people who work in finance. It wasn't obvious to me. But a basic law of the market is that the fastest person will usually win.

ANDREW ZOLLI: There's always a benefit ...

JAD: That's Andrew again.

ANDREW ZOLLI: ... to getting information faster than the other guy.

LARRY TABB: Absolutely. This has been going on since Julius Reuters used carrier pigeons ...

JAD: To send a bunch of stock quotes ...

LARRY TABB: ... faster than a guy on a horseback.

JAD: And that was in the 1850s.

LARRY TABB: Here's a more modern example. Say the latest job numbers come out.

[NEWS CLIP: US employers added 227,000 jobs in February.]

LARRY TABB: If those numbers are good, that means the stock market is going to go up. So if you can get the numbers and rush to the market before anyone else gets there and buy the stock before it goes up, you could make a lot of money, right?

ANDREW ZOLLI: On the, you know, buy-low, sell-high principle.

ROBERT: Basic law of—of getting rich.

JAD: But when the markets turned electronic, which began to happen in the early '90s, this basic law created a situation that was totally bananas.

ROBERT: What do you mean?

JAD: So imagine it's the year 2000. You've got this market in New York. It's electronic. It's basically just a building on Broad Street near Wall Street with a giant computer inside of it that's matching buyers and sellers. And you have a bunch of traders in different parts of the country that are connected to this market, to this building, and some of them are using automated trading bots. And one day, this guy Dave Cummings, who is in Kansas, notices that his robot keeps getting beat. Like, when it would send a trade to New York, like say a buy order, often right as that buy order was about to get to New York, some other robot would swoop in, get there first, and snatch up the trade. And it occurs to this guy, Dave, wait a second, is it because I'm in Kansas? If the other guy's closer to New York, then his cable would be shorter. So I need to move to New York.

ROBERT: No, no, no, because we're talking about the speed of light.

JAD: Well, close to the speed of light.

ROBERT: But still ...

ANDREW ZOLLI: Obviously, it's because he's in Kansas.

ROBERT: What do you mean, obviously?

ANDREW ZOLLI: Because the speed of light is like a foot a nanosecond. You're gonna get your ass kicked if you're in Kansas.

ROBERT: I don't even—do you know this for a fact?

ANDREW ZOLLI: Yeah, it's a foot a nanosecond.

ROBERT: It's a foot a nanosecond.

ANDREW ZOLLI: It takes a billionth of a second to go a foot. It's 3x10¹º.

ROBERT: [laughs] Why do you act like this is something everybody knows?

ANDREW ZOLLI: I—I know this because when I was in physics, like if I needed to delay a signal by a nanosecond, by a billionth of a second, I just added an extra foot of cable.

ROBERT: Really?

JAD: Did you really do that?

ANDREW ZOLLI: Yeah, 'cause the proton-antiproton would collide, and then it would create a muon that would go out. And you only wanted to measure—you want to filter all the junk so you knew when it was gonna arrive roughly. So you had a little, like, window. It had to arrive in the window. But you had to get the timing of the window right, so it meant, like, adding a delay. And we just would add cable. That was the easiest way to add.

ROBERT: So you would literally go get some—some cable and just splice it in?

ANDREW ZOLLI: Not splice it. LEMO—they're LEMO connectors.

ROBERT: Oh, they're LEMO connectors. Of course.

JAD: Here's another way to think about it. Like, say the time it takes for information to get from Kansas to New York is something like this. [beep beep] Did you hear that?

ROBERT: I did.

JAD: First beep is when it leaves Kansas. Second beep is when it arrives in New York.

ROBERT: Yes.

JAD: Actually slowed that down just a bit so we can hear it better. But the point is that is fast, but there's still a little space in there between the beeps, which is the travel time.

ROBERT: Very, very little space.

JAD: But even if these signals are traveling at millions of miles an hour, close to the speed of light, if somebody is a few hundred miles closer to New York than you and they leave at the same time as you, well, then it's gonna be like [beep beep beep] you hear that? [beep beep beep]

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: That beep in the middle is some other dude beating you by a few milliseconds.

ROBERT: These little differences matter?

JAD: That—they're trying to get in and out super fast, and maybe each trade, they're only making ...

ANDREW ZOLLI: A fraction of a penny.

JAD: That's it, says Andrew.

ANDREW ZOLLI: But if you're making a fraction of a penny, millisecond after millisecond after millisecond ...

JAD: It can add up.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Right.

JAD: But you have to be able to react really fast. So when this guy in Kansas decided to move his robot to New York to get closer to the big market computer ...

ANDREW ZOLLI: When this happened ...

JAD: ... it started kind of a land grab.

ANDREW ZOLLI: There was a real estate bubble around some of these buildings.

ROBERT: Really?

ANDREW ZOLLI: Because people were trying to buy physical real estate next to the exchanges so that the cables that they would run into the exchanges would be just a few feet shorter than the other guy.

ROBERT: Wait a second. So does this mean, like, if I'm, like, one stop up on the elevator and you're two stops up, that I have the—the second floor advantage? I mean, how far do you do this?

JAD: Theoretically, yeah. I mean, that's what it means. But I don't know how far this real estate jockeying got because pretty early on, the—the people who run the market stepped in and they were like, "Okay, this could get crazy." So they told the machine traders, "Okay, you want to be close to us? Fine. Pay us some money, we'll let you come inside."

ROBERT: Inside our box?

JAD: Inside the mothership!

ROBERT: Is there, like, some room where all these computers are keeping each other company now?

ANDREW ZOLLI: Oh, yes, there is.

JAD: If you visit the New York Stock Exchange now, which we did ...

JAD: So this is—where are we headed now?

JAD: ... after going through months of security checks, what you see is ...

IAN JACK: This is where the trades actually happen.

JAD: ... amazing!

ROBERT: Ooh!

JAD: Wow!

IAN JACK: So this is what, a 20,000-square-foot hall.

JAD: This is Ian Jack. He's head of infrastructure at the New York Stock Exchange. He showed us around.

IAN JACK: With a number of rows of racks for customer equipments.

JAD: In 2006, the New York Stock Exchange opened up this room. It's the size of three football fields, filled with nothing but ...

IAN JACK: ... rows and rows of servers, different specifications.

ANDREW ZOLLI: So these are owned by banks, hedge funds, brokers?

IAN JACK: Yeah, a whole number of financial institutions.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Are these things trading right now?

IAN JACK: Absolutely.

JAD: Each of these computers—and there were close to 10,000 in the room, give or take—were at that moment analyzing the market, making a decision as to whether to buy or sell, sending that decision over a cable into an adjacent room where it gets bought or sold. No people involved.

ANDREW ZOLLI: If you stood still for a few seconds, the lights went out. They automatically went off if nothing moved because the assumption was there were not gonna be people there.

JAD: And the whole idea of this place, says Ian ...

IAN JACK: The whole premise is a level playing field. So any firm can come in here and they'll have the same access as anyone else.

JAD: And to make sure of that—this is my favorite part ...

IAN JACK: Every single rack within this facility has the same length of cabling to get to the network points at the end.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Exactly the same length?

IAN JACK: Exactly the same.

JAD: ... everybody gets the same length cabling. Whether you're one foot away from the network hub or a thousand feet away, you get the same length.

ANDREW ZOLLI: I'm sure they send synchronized test pulses from both your trading computer and Jad's trading computer and they make sure they arrive exactly at the same moment.

JAD: I like to imagine they have a guy with a tape measure.

ROBERT: That's the guy you bribe. That's the guy!

JAD: Anyhow, you would think that since all machines can now be inside the exchange, literally inside the market building, that the speed race would be over, right?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: No. Actually, it only gets worse because the place we visited, the New York Stock Exchange, that's just one market of many. I didn't know this but apparently when all trading went electronic, the markets fragmented.

LARRY TABB: It used to be that to trade stocks, there was the New York Stock Exchange, and then there was NASDAQ.

JAD: Really just those two markets, says Larry.

LARRY TABB: Now, there are 13 regulated exchanges. There are roughly 50 what they call dark pools in the marketplace.

JAD: Those are non-public, basically.

LARRY TABB: Yeah.

JAD: So you got these 60-some-odd different markets, and that's created all these different speed races between them.

LARRY TABB: Yeah.

JAD: Here's a super basic example I talked about with Andrew. In Chicago, you've got this thing called the commodities market.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Commodities are basic goods like corn, oil, soybeans, zinc, pork.

JAD: That's what they do in Chicago. Here in New York, we do equities.

ANDREW ZOLLI: An equity is a share of a company.

JAD: So you have basic goods in Chicago, stocks of companies in New York.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Those are different kinds of things, but they're connected to each other.

JAD: You know, because, like, take oil, which is traded in Chicago. A lot of companies depend on oil, and they're traded in New York. So say oil goes up in Chicago, you can pretty much bet that right after that, a company like Exxon is going to go up in New York. But it won't be instantaneous.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Right. Because information has a speed.

JAD: Back in the days of the telegraph, as we've learned, it took a quarter second. About that long to get from New York to Chicago. Now with fiber optic cables, about 15 milliseconds.

ANDREW ZOLLI: I love that. I had no idea you could actually hear the time difference.

JAD: That one, I think, is pretty accurate. 15 milliseconds. But say you're in Chicago, oil goes up, you know it, and you can get to New York in 14 milliseconds. Well, you've got one millisecond where you know the future. You know exactly what's gonna happen. You're not even betting at this point. This is easy money.

MIKE BELLER: So what happened over time was a race of people to provide the straightest fiber line between Chicago and New York.

ANDREW ZOLLI: That's Mike Beller again from Tradeworx. He's part of this race.

MIKE BELLER: A couple of years ago, a company came along ...

JAD: Not his, unfortunately.

MIKE BELLER: ... and spent some eight-figure sum to cut a straighter fiber line between those two points. And ...

JAD: According to some reports, they blew through a mountain to do it.

MIKE BELLER: ... they did a lot. And where the state-of-the-art for communication lines at the time between the two locations was about 15.5 milliseconds, they came along and they made that state-of-the-art 13.3 milliseconds.

ANDREW ZOLLI: A savings of about one millisecond each way.

MIKE BELLER: Which is just an—it's just an eon.

ANDREW ZOLLI: It's just a thousandth of a second you're talking about. That's not an eon.

MIKE BELLER: Well, it's an eon when your computer system is able to make a decision in 10 microseconds, which ours are.

JAD: That's 10 times faster.

ANDREW ZOLLI: So your computer is like, "I could do this so fast, but I'm just waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting for the news from Chicago."

JAD: [laughs]

MIKE BELLER: So a lot of us were sitting around thinking, "What can we do about this?"

ANDREW ZOLLI: Turns out, there was a way to get from Chicago to New York a little faster because the speed of light through air it's a little faster than when you're going through a fiber optic cable. And so what they're doing now is they're building a series of towers so they can beam the signal through the air from one tower to the next tower to the next tower, all the way from Chicago to New York.

MIKE BELLER: So ...

JAD: And that would bring the travel time down to about ...

MIKE BELLER: In the neighborhood of around 8.5 milliseconds.

JAD: So you're going from 13 to 8.5?

MIKE BELLER: Yeah.

JAD: That would be going from this ...

[quick beep]

JAD: ... to this.

[quicker beep]

JAD: I mean, come on!

MIKE BELLER: That's a lot of potential savings.

JAD: I can totally hear the difference.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Is it helping? Is it—are we fast enough now? Can we stop?

MANOJ NARANG: Here's the thing.

ANDREW ZOLLI: That's Manoj Narang, the CEO of Tradeworx. He joined us for part of the interview, and he told us, actually, we would love to stop this arms race.

MANOJ NARANG: Yeah, absolutely. The arms race is a huge drain on resources.

ANDREW ZOLLI: But he says we just can't.

MANOJ NARANG: As it stands, when a new technology comes out that makes it possible to be faster, if I don't adopt it and my competitors do, I will lose out to them. I have to do it.

JAD: And looking at Manoj in particular, you could kind of tell that this part of the job ...

MANOJ NARANG: It's just like the plumbing.

JAD: Yeah, it just kind of makes him weary.

MANOJ NARANG: Yeah, I couldn't care less.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Why not just call it a truce and everyone say we're not gonna try and go faster? We're already way faster than any human can think. It's fast enough. We're gonna ...

MANOJ NARANG: Why not call it truce? Because there's such a thing in game theory called Prisoner's Dilemma, and…

ANDREW ZOLLI: Someone will cheat, you're saying, basically.

MANOJ NARANG: Yeah. You can't put a gun to everyone's head and force them to abide by this truce.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Even though we'd all be better off if you could.

MANOJ NARANG: Well, who would be better off?

JAD: And here, Manoj told us, "Look, even though this speed race sucks for us, it's actually helping you." Because on a basic level, anytime you replace a human with a computer, things are gonna get faster, they're gonna get cheaper. And now that the machines are competing, getting cheaper still. In 1992, it would have cost you about $100 to trade 1,000 shares. Now? 10 bucks.

MANOJ NARANG: So yes, humans have been completely supplanted when it comes to short-term trading. And humans who complain about that are being disingenuous, okay? They have not been displaced by anything other than the fact that they can't compete.

ANDREW ZOLLI: You seem like you've had the—you seem defensive.

MANOJ NARANG: Well, just because I can explain the economics of the business doesn't make me defensive.

JAD: [laughs]

ANDREW ZOLLI: That also sounded defensive.

MANOJ NARANG: [laughs]

JAD: If Manoj did sound defensive it's only because he and Mike and everyone in their industry have had to answer a lot of questions over the past few years about where all this speed is taking us. And those questions always come back to one particular day, May 6, 2010, when things got a little fruity.

ROBERT: [laughs]

ERIC HUNSADER: We hadn't had a down day in a long while. The market had been solely creeping up for quite a while.

JAD: That's Eric Hunsader again, the analyst who's been tracking high-frequency trading. He says that day, even though things had been going really well ...

ERIC HUNSADER: That day had started off down pretty hard.

JAD: Which made some sense because there was bad news coming out of Athens. People were nervous. But then at a very specific moment, 2:42 in the afternoon ...

ERIC HUNSADER: 14:42 and 44 seconds ...

JAD: ... all hell breaks loose.

[NEWS CLIP: Okay, Neil, let me just—let me just interrupt for a second because this market is dropping precipitously. It just went -500. It is now -560.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, floor trader: I need an offer, seven need an offer, six halves are trading here now!]

[NEWS CLIP: The Dow was losing about 653 points. Now Dow is down 707 points.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, floor trader: …The 79's are trading.]

[NEWS CLIP: Boom, there it goes.]

[NEWS CLIP: Look at this market. It continues to slide.]

[NEWS CLIP: Look at it! 835.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, floor trader: This is the widest we have seen this in years.]

[NEWS CLIP: Now it's down 900.]

[NEWS CLIP: Wow, almost 1,000 points.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, floor trader: This will blow people out in a big way like you won't believe.]

[NEWS CLIP: Cancel all orders down 1,000 points. Cancel all orders!]

JAD: At 2:45 and 27 seconds an emergency circuit breaker shuts off ...

ERIC HUNSADER: For five seconds, and that was the end of the slide. When it went out and stopped for five seconds, that was the bottom of the market.

JAD: 1,000 points down. Several hundred billion dollars vanished.

ERIC HUNSADER: Two and a half minutes.

JAD: Equally weird, when trading started again, the markets bounced right back up.

ERIC HUNSADER: About two and a half minutes later, it was 600 points higher than the bottom.

JAD: It was like—foom! Boing! Now these kind of swings had happened before, but never that fast. And the speed is one thing. Arguably, what's more troubling is that we still, two and a half years later, don't really know what happened. I mean, the SEC investigated for months, released this giant 84-page report where they essentially blamed the whole thing on one bad algorithm. That this guy in New York was trying to sell a bunch of stocks, told his computer to do it. His computer just did it a little too aggressively.

ERIC HUNSADER: No, that's not how it went down at all.

JAD: Eric doesn't agree. He thinks what happened is that all the high-frequency computers just clogged the network.

ERIC HUNSADER: Really, the cause of the flash crash was system overload.

JAD: Because he says a basic feature of these computer algorithms is when they detect that the network is slow, they pull it out.

ERIC HUNSADER: I mean, one of the maxims on the street is "When in doubt, stay out or pull out."

JAD: And so if you've got this one computer selling a ton of stock and no computers left to buy, that creates a vacuum.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Now there were people who argued that high-frequency trading had actually made the situation better.

JAD: Because, you know, Andrew says the markets did bounce back.

ANDREW ZOLLI: Right up to the top.

JAD: The computers self-corrected, perhaps.

ANDREW ZOLLI: But the point is nobody had any idea.

JAD: And that's what gets him. That we're in a situation now where when things go wrong, they go wrong in the blink of an eye, and then it takes us years to figure out what happened?

ANDREW ZOLLI: The question that comes up is: have we crossed some kind of Rubicon where we've passed into a realm where the complexity, speed, the volume of all this stuff makes it no longer human-readable? We just don't know what the system is doing and can't, in principle, find out when things go wrong.

JAD: Big thanks to David Kestenbaum for joining me. If you don't listen to NPR's Planet Money, you definitely should. Definitely. Check them out at NPR.org/money. And thanks to Chris Berube, who carried a heavy load with the reporting on this segment. And also sound artist Ben Rubin.

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.