Jun 6, 2013

Transcript

ELLEN HORNE: Do you want to get out?

JAD ABUMRAD: Is this—is this us?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah, this is us.

JAD: Okay.

JAD: This is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad. Since our program today deals with stumbling upon the past in unlikely places, we thought we'd begin this part of the show well, not at a place we'd normally visit.

JAD: So I feel like we're standing on top of a mountain, but how high up are we?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Right here I believe we're about 180.

JAD: This, by the way, is Chief Dennis Diggins.

DENNIS DIGGINS: I'm an assistant chief in the New York City Department of Sanitation.

JAD: And when he says 180 he means feet.

DENNIS DIGGINS: About 180 feet high.

JAD: Wow, so that's about 18 stories.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Correct.

JAD: 18 stories up into the Staten Island sky, that's where we're standing.

JAD: Where we're standing.

JAD: On a hill.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Basically like a big dirt hill.

JAD: And at a glance, you would never know that this hill was made from anything other than dirt.

JAD: What did this used to be?

JAD: Unless, of course, you dug about a few feet down.

DENNIS DIGGINS: This is all garbage underneath us. Up until March of 2001, we were taking in all of New York City's garbage.

JAD: All the boroughs were coming here?

DENNIS DIGGINS: All the boroughs were coming here. So we were probably taking in on average 11,000 tons a day.

JAD: 11,000 tons a day. That's—what does 11,000 tons look like?

DENNIS DIGGINS: [laughs] It's a lot of garbage.

JAD: Fresh Kills used to be the biggest dump on the planet. But that's all in the past. With a little engineering help ...

DENNIS DIGGINS: It's gonna be a great park. Absolutely.

JAD: ... this will be a park.

DENNIS DIGGINS: I mean, just look at how much property you have. You take ...

JAD: All these mounds are getting wrapped in plastic and covered with grass. There will be a restaurant ...

JAD: I can almost imagine that.

JAD: ... even a golf course.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah, I would love to be the first one to tee off on that.

JAD: [laughs]

JAD: But underneath it all, the garbage will still be here. 50 years of trash, waiting patiently until someone comes to look for it—and someone always does.

DENNIS DIGGINS: I know years ago we—there was a—a garb—an arch—how do I say it right? An archeological garbageman that came here and he did some core sampling.

JAD: Meaning with a special tool, this guy bored a hole deep into the center of the mound.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Actually came up with a—a hot dog. Landfilled 10 years previously.

JAD: Are you kidding me?

DENNIS DIGGINS: So ... [laughs]

JAD: Hot dog that was 10 years old and was still a hot dog?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah it was still a hot dog.

JAD: Recognizably a hot dog?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah, recognizably a hot dog. So that's ...

JAD: That's amazing and disgusting.

DENNIS DIGGINS: [laughs] I still like hot dogs so I'll eat them, but ...

JAD: No, but seriously, do you ever consider the history that's contained in this—in this big chunk of garbage?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Oh, yeah. Well, this is one big time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time cap ...

JAD: You can stop—stop saying that now. Thank you. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab, a series about science and discovery. And that is exactly what we have for you today: three detective stories.

ROBERT: And each one begins with a rather peculiar clue.

JAD: Clues that lead you back into the past.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

JAD: And now that we've got that phrase in our minds, and garbage as well, let's go to a different part of the world and get things started for real, to a different time also. 1898, Egypt. Oxyrhynchus Egypt. You with me?

ROBERT: Where is Oxyrhynchus Egypt?

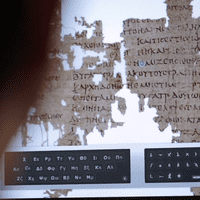

JAD: It's in the south, in the desert. South of—of Cairo, I think, and it—and let me show you a picture.

ROBERT: All right.

JAD: You see the desert?

ROBERT: Oh yeah. It's a big flat sort of sandy place, and these—who is this guy?

JAD: Well, you should see two guys, they are—they are two Oxford archeologists.

ROBERT: Yeah with a pith helmet, and sort of standing high on a mound, looking down.

JAD: Yeah, one guy is on top of the mound, the other guy is towards the bottom. That's Grenfell and Hunt, two Oxford archeologists. They were in Egypt in 1898 looking for treasure and they find those sand dunes.

ROBERT: Mm-hmm. Which don't look quite like the other sand dunes, really. They're sort of ...

JAD: Yeah they're sort of—sort of strange, and irregularly shaped. Which is why when they saw those sand dunes that you're looking at, they hired a team of workers and they started to dig. And they immediately began to find things.

DIRK OBBINK: Huge quantity of pottery, clothes, shoes, baskets, rope.

JAD: That's Dirk Obbink, a scholar from Oxford. He tells the story of what they found, and what they found was basically ...

DIRK OBBINK: The motherlode. A huge circle of rubbish mounds, over 20 of them that were completely undisturbed.

JAD: This was no piddly little trash heap that was 50 years old like you might find in Staten Island. These mounds were really old.

DIRK OBBINK: These were rubbish mounds that had built up over the course of 10 centuries.

JAD: 10 centuries of trash.

ROBERT: [gasps] That's 1,000 years of trash. [laughs]

JAD: Yeah, and that included a lot of ancient paper. That's what they were really interested in. Any scraps or scrolls they could find.

DIRK OBBINK: And one of the first ones that they pulled out of the ground was Lost Sayings of Jesus.

JAD: What?

DIRK OBBINK: That was the first one that they pulled out of the ground.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: He who knows the all but fails to know himself lacks everything. If they say to you whence have you come ...]

JAD: Okay, forget the 10-year-old hot dog. Here we have sayings of Jesus which have not been seen, read or even heard about for almost 2,000 years.

DIRK OBBINK: A long list of sayings that are not in the canonical books of the Bible.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: He who seeks let him not cease seeking until he finds ...]

JAD: This is a different Jesus than the one in the Bible. It's almost Eastern in tone, he says, "Heaven is here."

[ARCHIVE CLIP: The kingdom of the father is spread out upon the Earth.]

JAD: It's all around us.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: And men do not see it.]

JAD: If we just opened our eyes.

DIRK OBBINK: It's a papyrus that today is known as the Logia Fragment.

JAD: And there it was buried in the trash.

ROBERT: Wow!

JAD: Anyhow, the team pulled as much paper as they could from the mounds, separated out all the shoes and stuff and just took the paper.

DIRK OBBINK: And then they packed those up with hundreds of boxes, and shipped them back here to Oxford.

DIRK OBBINK: This is the Sackwood library in Oxford, and we're still today, 107 years later ...

DIRK OBBINK: We're—we're going upstairs now.

DIRK OBBINK: ... we're still today opening those boxes, pulling out the fragments, piecing them back together and deciphering them.

JAD: This is what 2,000-year-old paper sounds like. Sounds just like paper, and it looks like dried leaves. Not really much to look at or listen to, but knowing that it's 2,000 years old and theoretically could've been written on by Jesus himself? Well, it makes it a little more special, which is why we visited Oxford, England, where the dump now lives, packed away in 700 boxes.

NICK GIANNIS: This is a box that contains about 600 unpublished papyri.

JAD: Nick Giannis, one of the collections curators popped one open for us.

NICK GIANNIS: I'm just opening an official document sometime early in the fourth century. Of course, it's full of—of holes, probably caused by little worms.

JAD: And there's the sad part: there are enough secrets in the boxes to rewrite the past. The problem is ...

NICK GIANNIS: Much of this is hopelessly fragmented.

JAD: ... reading it is almost impossible.

NICK GIANNIS: Some of the smaller fragments if you see lots of them, it looks like a conglomeration of corn flakes. It will be a few hundred years before even the most substantial of these fragments come to light.

DIRK OBBINK: We're talking about the reconstruction of works that—the work on which is beyond the scale of a single human lifetime.

JAD: Way beyond. In the past 107 years, the Oxford team has worked their way through a whopping one percent of the collection. It may take another 10 centuries to get through the rest. Here's how it usually goes: Nick scours the boxes each day, finds a new scrap, tiny little scrap, and brings it into the lab for cleaning.

DIRK OBBINK: What I do now is I remove some ancient mud with the help of a brush.

JAD: Here he wipes ancient mud from a torn page of Homer's Iliad. After it's mud free, each piece is cataloged in the computer.

DIRK OBBINK: For various features like type of handwriting, size and style.

JAD: And if the piece seems to match another pieces, Dirk and maybe a grad student spread them all out on a long wooden table and basically from there it's a classic jigsaw puzzle.

DIRK OBBINK: How about this one? Doesn't it look like these might be the line beginnings of ...

JAD: They move one here.

NICK GIANNIS: I think that—that looks like a promising match.

JAD: See if the words match up.

DIRK OBBINK: Because they seem to line up pretty exactly with the lines of the larger fragment.

JAD: May take five minutes, may take five years, may take five lifetimes. But eventually they will have—well, not the whole story. Not even a page of the whole story. But something.

NICK GIANNIS: I've put the papyrus under a—an electronic microscope.

JAD: Maybe just a few Greek words from the deep past.

NICK GIANNIS: [speaking Greek]

DIRK OBBINK: [speaking Greek]

NICK GIANNIS: But we're missing a bit from the upper right corner.

DIRK OBBINK: Sometimes a sentence breaks off just when you need it to tell you what you need to know. We have to be satisfied with knowing a little rather than a lot.

ROBERT: Let me make sure I understand this. Is each of these fragments just a teeny—like is it "To be, or?"

JAD: It's more like, "To."

ROBERT: [laughs] Oh, it's that small?

JAD: Some of them are tiny. Tiny. I mean, there's about a half a million in total.

ROBERT: Half a million!

JAD: And—and they've only got through about 5,000.

ROBERT: Well is—do you have in your own list of things like a sort of favorite hits list?

JAD: I do. I do. I've narrowed it down to my top three.

ROBERT: Oh, okay!

JAD: My top three ancient garbage greatest hits, if you will. Which was difficult, but here are three that are really interesting.

ROBERT: First, number three!

JAD: Ancient Garbage Greatest Hits number three. You, being a death metal fan, I'm sure are familiar with these three inauspicious numbers.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Iron Maiden "Number of the Beast": 666, the number of the beast. 666, the number of the beast. Yeah!]

ROBERT: Absolutely! 666, sign of the beast.

JAD: Right. Just to explain: the number of the beast, 666, is what you use to either summon the beast or keep the beast away because you can't say his name directly. That would be bad. All this comes from the New Testament.

DIRK OBBINK: Okay.

JAD: Dirk showed me a piece of papyrus that he found in the dump. It's about the size of your palm.

JAD: So what are we looking at? This looks like this may be 30 letters.

JAD: A copy of precisely that passage in the New Testament where the number is stated.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Vincent Price: Let him who hath understanding reckon the number of the beast. For it is a human number. Its number is six hundred and sixty six.]

DIRK OBBINK: 666, which was the traditional number of the beast.

JAD: Now here's the thing: this little scrap of papyrus that Dirk turned up is the earliest known copy that we have of that passage. He showed me ...

JAD: But can you—can you point to the letters again and show me ...

JAD: ... its three numbers are smack in the center of the papyrus.

Dirk Obbink: Three Greek letters: Chi, Iota and Sigma.

JAD: Chi, Iota, Sigma.

ROBERT: Chi, Iota, Sigma.

JAD: Should say 666, right?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: But, in fact, Chi, Iota, Sigma don't say 666.

ROBERT: They don't? What do they say?

JAD: 6 ...

DIRK OBBINK: 616.

JAD: ... 16.

ROBERT: No!

DIRK OBBINK: Instead of 666.

ROBERT: Really?

JAD: Yeah!

ROBERT: Does that mean all the bibles are wrong, or ...

JAD: Maybe. I mean, all we really know is that the number of the beast had versions.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: And that 616 may be the original.

ROBERT: Oh!

JAD: How long does it take this to filter into the King James Bible or something like that?

DIRK OBBINK: Oh no, it will appear in the next standard edition of the New Testament in a note on that page representing it as a viable variant that has now appeared in a papyrus text.

ROBERT: What—what—do biblical scholars accept this?

JAD: They do.

ROBERT: Oh, so you should just probably be very careful about six blank six for the—if you are worrying about the beast.

JAD: Well you should probably change your tattoo. [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs] Shhh!

JAD: Okay. Let's move on to number two. Garbage Greatest Hits number two.

JAD: Hey, did you see the movie Troy?

ROBERT: Yes.

JAD: You remember this scene?

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Troy: "Hector!"]

ROBERT: Big, bold, muscular men fighting big, bold, muscular fights with big, bold, muscular enemies.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Troy: "Hector!"]

ROBERT: I know the film, and I know how big, bold and muscular it was.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Troy: "Hector!"]

ROBERT: What did your scrap tell you?

JAD: Well, the papyri folks recently—this is big news in the world of the papyrologists, they got their hands on this special camera.

PAPYROLOGIST: So we have this digital setup here, a camera on a—on a sort of easel.

JAD: This camera uses infrared filters to photograph text that's so faded that you can't really see it with the naked eye.

PAPYROLOGIST: Take a—quite a long exposure.

JAD: In any case, the first thing they read with that camera is a poem about the Trojan War.

DIRK OBBINK: The new poem of—of Archilochus.

JAD: This poem.

DIRK OBBINK: [speaking Greek]

JAD: Comes from the 600s.

ROBERT: Oh, it's not Homer, it's Archilochus's version.

JAD: No, it's precisely not Homer because whereas the Homeric version, the Brad Pitt version, it goes, you know: Greeks invade, Troy falls, hoorah. This version goes: Greeks invade, get their butts kicked, then run. Run like sissies.

ROBERT: Oh! [laughs]

DIRK OBBINK: So it completely turns the Homeric account on its head.

ROBERT: Wait, wait, wait, wait. So this—this was written at the same time as Homer?

JAD: A little bit later, but in response to Homer.

ROBERT: Oh!

DIRK OBBINK: And the Greek goes like this.

JAD: Here, listen.

DIRK OBBINK: [reading Greek version] "One doesn't have to call it weakness and cowardice having to retreat. No, there does exist a proper time for flight."

JAD: See, Homer's notion was, like, that the hero stands and fights to the end, but this poet was saying, "You know what?"

DIRK OBBINK: No ...

JAD: "We ran away."

DIRK OBBINK: We turned our backs to flee quickly.

JAD: "And that's okay."

DIRK OBBINK: He actually celebrated it as something that he was proud of because sometimes you had to turn and run.

ROBERT: Running away is a good thing.

JAD: Running away is a good thing.

ROBERT: That's a good one.

JAD: See, what's interesting about the past you find in the trash is that it's messy, it's complicated. There's not just the story you know, there's contradictions to that story, competing accounts of that story, which can be disconcerting. I mean, you know, who wants to have different bibles floating around? That could be weird for people. But to me, to know that way back when, even then there were different ideas about what it means to be a hero? That I find comforting. Which brings us to my first choice.

ROBERT: And last but hardly least.

JAD: Ancient Garbage Greatest Hit number—well the greatest hit. What do you think people in the first century were reading?

ROBERT KRULWICH: What do I think they were reading?

JAD: Mm-hmm. What do you think they were really reading?

DIRK OBBINK: Okay when the—when the text starts she's saying, "Oh, I'm terribly on fire." And that goes in Greek [reading Greek] The translation: "Uh oh, it's thick and big as a roof beam."

ROBERT: [laughs]

DIRK OBBINK: And then she goes on. "Manai, cat of ..."

JAD: Porn, that's what they were reading. This filthy satire turned up enough times in this and other dumps for Dirk to suspect that they may have been a bestseller.

ROBERT: So there was more than one version of this?

JAD: It appeared over and over and over.

DIRK OBBINK: "I'm burning, I'm on fire, I'm terribly on fire. A stream runs over me. Do you understand?"

JAD: This is Radiolab, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: And I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Our show today is about finding clues to the past in the weirdest places, and there is no weirder place to find the past than in the story you're about to hear. Comes to us from Laura Starecheski, who herself likes to get into old things.

LAURA STARECHESKI: My—my mom kind of fostered that. Like, when we were little, one of our outings that we would do would be to go to this toxic dump near my house where I grew up. It's, like, on top of a mountain. They sealed off this mountain and they made all the people move off of it, so you're just walking along a trail and then you see all these old abandoned houses full of stuff. So we would go into the houses and we'd find pay stubs, we'd find dishes, we'd find paintings, and we'd try and figure out why—like, even though we knew really why the people had left, we would try and make up other stories about why they left, like, maybe they were fighting in the middle of dinner and they just had to leave all their dishes on the table.

JAD: All right. Fast forward many years, Laura's in New York, and one day she gets a call from her sister who tells her, "I just heard the most amazing story. I was at my writing class and the teacher told us this story. You should call him, Eric Gordon is his name. Take your tape recorder over to his office in Manhattan, make him tell it to you." So that's what she did.

LAURA: I just said at first, you know, I just want to record you telling this story.

ERIC GORDON: Hey, how you doing?

LAURA: Hey, how's it going?

LAURA: How he had found all his letters and photos and created a character. I had no idea that I would become so involved.

ERIC GORDON: Okay.

LAURA: So do you want to talk about that day, like, that the story took place?

ERIC GORDON: Sure. That day, let me see if I can put myself back in that day. So I was living in Oakland at the time.

LAURA: This is about 1994.

ERIC GORDON: And decided to go on a weekend camping trip with a friend. And we're driving south on Route 101 through the central part of the state, and my friend starts to frantically shout. "Look! Look!" And she's pointing out to this field. She can't even get the words out. She's saying "Look! Look!" And she's shouting.

LAURA: So he tries to look ...

ERIC GORDON: And I turn my head very quickly.

Laura: ... and he can't see because his view is blocked by an overpass or a hill, and he just has no idea what she is talking about.

ERIC GORDON: And she is stuttering her words and she says, "Th—th—there's" and she's still stuttering. And she says there is a goat standing on a cow's back.

Laura: And she's like, "There is a goat standing on a cow's back in that field."

JAD: A what?

LAURA: A goat standing on top of a cow.

JAD: A goat standing on top of a cow?

LAURA: Yeah.

ERIC GORDON: And, you know, of course my reaction is—is that's absurd. And she's saying "Pull this truck over. Pull over!" And she's getting really angry. And I said, "I'm not backing up three quarters of a mile on 101."

LAURA: So they argue for a little while, and Eric finally relents. 20 minutes later they arrive back at the field.

ERIC GORDON: So we pull over, and she just gets the hugest grin on her face. There is, in fact, a goat standing on a cow's back.

LAURA: Still there.

ERIC GORDON: We sit in the truck for a minute watching this cow, who's close enough to the fence that we've got a very good view of it. And every time he takes a step to graze, the goat kind of shifts from side to side balancing.

LAURA: So they're kind of this unit.

ERIC GORDON: It was, I mean, really amazing. You actually could see the goat's hooves kind of bunch up in the cow's skin.

LAURA: And they slowly get out of the truck to get a better look.

ERIC GORDON: And right as I shut the door ...

LAURA: The goat jumps off.

ERIC GORDON: The goat jumps off. And it just—you know, we're standing there kind of dumbfounded. We move up to the fence and just ...

LAURA: Believe it or not, the story gets weirder.

JAD: Really?

LAURA: Yeah. So Eric and his friend are standing totally still hoping that if they just wait maybe the goat will jump back onto the cow. And all of a sudden, Eric's friend notices something at her feet.

ERIC GORDON: She bends down and picks up a letter.

LAURA: A letter.

ERIC GORDON: Right in front of the fence.

LAURA: And it's old.

ERIC GORDON: And it's kind of ...

LAURA: Like 50 years old.

ERIC GORDON: ... like a crisp brown. Then we looked at the postmark and it was 1952. I open this thing up and read it, and it's almost about nothing.

ERIC GORDON: "My dear, I wrote you a card after receiving the first one."

ERIC GORDON: Yeah, see some of these were so tough to read. So I look down on the ground and there's another letter.

ERIC GORDON: "I've been slowly getting on my feet again."

ERIC GORDON: And another.

ERIC GORDON: "Ed is so much better."

ERIC GORDON: Looks like that's her looped F.

ERIC GORDON: And another.

ERIC GORDON: "Albertine sings very well indeed, since you ask. She took ..."

ERIC GORDON: They were blown, literally, in this line down the side of the highway. And we looked at each other and frantically started gathering these letters, filling our arms with them. Letters from the 1920s, I see a 1937 postmark. And then she shouts from a couple feet away, "1897! 1890!" I'm gathering, my arms are getting full, I run to the truck and grab a garbage bag and I start filling it up, and then I start to notice: Ella Chase. Ella Chase. Ella Chase. Ella Chase. These letters are all written to the same woman.

LAURA: Over 300 letters all written to one woman, Ella Chase.

ERIC GORDON: You know, forget the goat and the cow, now we're standing in the middle of somebody's whole life correspondence spread out on the side of Highway 101. And we just read. And we read and we read into the night. Let me see if I can find—it's a really old ...

LAURA: So that day back in 1994 began a 12-year obsession with Ella Chase. These letters are maybe Eric's favorite thing in the whole world. He keeps them in this big archival box in his closet.

ERIC GORDON: Now what's really interesting is there are a ton of letters that are written to her as "Mother," or "Mom." And ...

LAURA: First thing Eric pulls out is a big stack of letters written to Ella during World War II.

ERIC GORDON: Probably have 40 letters from boys in the Navy to Ella Chase with that "Read By Censors" stamp on the letter where they're calling her "Mom." I'll read you one, and this is one that I—April 2, 1941, from a GI named W. Murphy. And he writes, "Well Mom, I hope you don't mind me calling you this, 'cause you were swell to me and just a mother to me and I hope that I can be seeing you again. And keep writing to me if you will. I sure enjoyed hearing from you. Hope you received the letter that I wrote a few days ago, but mail is a little slow going and coming out here. I'm feeling fine, only a little tired, but that's nothing unusual as we are pretty busy all the time. Oh, ma, I better close and say a prayer for me if you will and God bless you. Love, W. Murphy." August 3, 1945. Somewhere.

JAD: Dear mom. Were these her kids?

LAURA: No, they're not her kids. They're boys, 18-20 years old who are so attached to her just by writing to her that they started to call her "Mom." And there were like 40 of these letters.

ERIC GORDON: And a number of them from what I can tell in the letters have never actually met her. So she became this matriarch to all of these men in the war.

LAURA: I had never seen anything like that before.

ERIC GORDON: Yeah, there's so much. Something like this. I mean this is ...

LAURA: I was just amazed by the reach of her personality. You know, he showed me dozens of letters thanking her.

ERIC GORDON: You know, you look at this, "I am so very grateful ..."

LAURA: "Thank you for what you did for my husband."

ERIC GORDON: "He is ..."

LAURA: "Thank you for changing the way that I think about my life."

JAD: Whoa!

LAURA: And these seem to be from people who had only met her once.

JAD: Really?

LAURA: Yeah.

ERIC GORDON: The reverence that—that people just speak to her, and, you know, I can't figure out when she was married, I can't figure out where she was married. She ran for political office. I mean, this is a fascinating woman. She ran for political office in the 1940s, but I don't know what office.

LAURA: And that's where the story ends.

JAD: That's where the story ends?

LAURA: Yeah.

JAD: What do you mean?

LAURA: Eric has never tried to find out anything more. Remember how I told you he was a teacher before?

JAD: Yeah.

LAURA: He started bringing all these letters into his classroom, and ended up designing this whole curriculum around them.

ERIC GORDON: I collaborated with the history teacher. The kids would each get a photograph. They'd have to put it in a plastic sleeve. Each one of the kids whenever they handled them had to put on the surgical gloves. And history—the students would research that time period, and then ultimately they'd bring that work back to my classroom, my English classroom, and they would start writing historical fiction.

LAURA: Eric would ask each student to create a ghost biography of Ella Chase.

ERIC GORDON: This woman's history.

LAURA: Using her letters as a springboard.

ERIC GORDON: And some of the—you know, some of the pieces were wonderful.

LAURA: He ...

ERIC GORDON: Just incredible.

LAURA: He even had them title their papers "My Ella."

ERIC GORDON: And that's what's been much more meaningful to me.

LAURA: So the way Eric sees it, the real Ella was abandoned and he's given her new life.

ERIC GORDON: You know I feel like a guardian of this person's moment on the Earth.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, airport announcement: Good morning, ladies and gentlemen, this is a pre-boarding announcement for flight number 169 to San Jose, California.]

LAURA: So here's the thing: I was already going to California to visit a friend, and I couldn't leave things the way they were. Like, the whole time when I would look at these letters and look at the pictures, I would feel like there's more here.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, airport announcement: And our flying time to San Jose will be approximately five hours and 56 minutes.]

LAURA: How did someone who reached out to all these people end up with their life on the side of the highway?

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Airport Announcement: In-flight crew members prepare for arrival.]

LAURA: I really wanted to know.

LAURA: Do you wanna see some of this stuff? 'Cause I brought it.

MARINA COLE: You brought some?

LAURA: I knew I'd need help, so I contacted this friend of a friend, Marina Cole. She's this amateur expert in genealogical research. And I showed her the letters.

JAD: Wait, you had the letters? Did Eric give them to you?

LAURA: Yeah, even though he was convinced that they were abandoned. He told me, you know ...

ERIC GORDON: I would love to find family that this would truly mean something to.

MARINA COLE: Dear mom?

LAURA: It's—it's not her son. It's one of these letters from the World War II soldiers who all called her "Mom."

MARINA COLE: Oh, wow!

LAURA: Soon as I started showing Marina the letters her face kind of lit up.

MARINA COLE: Wow, she is amazing!

LAURA: The first thing we decided to do is to go to a historical society.

MARINA COLE: This woman, we know that she lived in Lomita Park.

MARINA COLE: Since this is for Daly City, I assume ...

MARINA COLE: So I went back and looked at census records to find out a little bit more about her.

LAURA: We found out that Ella had two granddaughters who were still alive, so we sent letters to her granddaughters but they'd never respond.

LAURA: Day two.

MARINA COLE: Stay straight to go onto Napa Valley Highway.

LAURA: My idea, my fantasy this whole time has been we'll go to her house—the address that's on the letters.

MARINA COLE: Well, it's worth a shot.

LAURA: Yeah, why not. Maybe bring one of the letters?

LAURA: It was a single story house, little rose garden. I think houses have a strong history. Someone there will be able to tell us something about her.

MARINA COLE: Are they coming?

LAURA: I don't know.

MARINA COLE: Huh.

LAURA: No answer. So we tried a neighbor.

NEIGHBOR: What is it you want?

LAURA: Hi, I'm sorry to bother you, I'm looking to find information about a woman who lived in this house ...

NEIGHBOR: I have no idea, we're new here in Napa.

LAURA: Okay, well thank you so much. Ugh. The missing husband?

MARINA COLE: I can't find anything on him at all. He's a complete mystery.

LAURA: I mean, there were a lot of unanswered questions, so we knew that we had to find Ella's obituary. Day three, the Napa Public Library. We're in front of the microfiche and we're scrolling through dates.

LAURA: It's August 22nd.

LAURA: This was kind of our last hope.

MARINA COLE: Look!

LAURA: [gasps]

LAURA: The death notice comes up on the screen.

MARINA COLE: Chase in Napa. Monday, July 4, 1955.

LAURA: We scan it as fast as we can for any new names that we haven't seen before. Almost right away we notice ...

MARINA COLE: Robert!

LAURA: Robert Lyely.

MARINA COLE: There was a grandson.

LAURA: A grandson. We had never seen this name before. [phone rings] He was listed.

[ANSWERING MACHINE: Hi this is Bob. Hi, this is Carol. We're either down at the store getting some milk or—we don't know where we're at but we're somewhere. Bye. Beep.]

LAURA: Hi, this is a message for Robert Lyely. My name is Laura Starecheski. I'm a reporter, and I'm doing a story about a woman who I believe is your grandmother.

LAURA: I wanted to hear a voice. I wanted a voice. Marina returned to Los Altos to get back to her life. And I waited. One day passed. Then another. I didn't get a call back from him. Day six. [phone rings] It was Marina.

LAURA: Marina?

MARINA COLE: Ugh.

LAURA: She hadn't been able to stop researching.

MARINA COLE: It's really sad.

LAURA: What is it?

MARINA COLE: Well, in 1938 she filed for divorce.

LAURA: Uh-huh?

MARINA COLE: And there's this series of articles where he denies that they were married.

LAURA: Really?

[VOICEOVER: She pleaded with me to marry her, Ella did. But we couldn't get along, and I refused to do it.]

MARINA COLE: She was desperate for money.

LAURA: Mm-hmm.

MARINA COLE: Needed to sell the house. She couldn't do that without divorcing her husband.

[NEWS CLIP: Trial of sensational I'm Not Married case expected in June.]

LAURA: It went on for like a year, the huge headlines. Ella said they were married. Belman, her husband, says that they never were. Ella couldn't produce a marriage certificate, and then finally the whole thing ended with her just sitting in the courtroom refusing to answer questions.

[NEWS CLIP: Ella A. Chase of Lomita Park, still adamant and defiant, but this time alone, steadfastly refused to answer questions.]

MARINA COLE: And then ...

LAURA: And that really wasn't the worst of it.

MARINA COLE: And then I found this really sad article.

LAURA: From a few years later.

[NEWS CLIP: Christmas 1942. Death took no holiday. On Christmas Eve, Belman Chase wandered along, dimmed out south of Market. He had been drinking heavily. He was separated from his wife and family. Perhaps he was trying to erase thoughts that come to men at such times. Christmas Day, sprawled on his back on a sidewalk, he died. The warm sun shone clear on the fractured nose and the blue bruise on his chin. "Looks like the bum is dead," someone said.]

MARINA COLE: Couple days later it says that his body was left unclaimed in the morgue.

LAURA: Really?

MARINA COLE: And they were not able to locate his estranged wife.

LAURA: Really?

LAURA: It suddenly made sense. It was right after that that she started writing to World War II soldiers. She probably needed them as much as they needed her. Day Seven. Holy Cross Cemetery in South San Francisco.

MARINA COLE: Oh, look. Look!

LAURA: Wow! Ella.

MARINA COLE: That's a nice headstone.

LAURA: It is a really nice headstone.

LAURA: It was gray and unpolished, and she was buried with her mother and father.

MARINA COLE: I wish I'd brought flowers.

LAURA: I know. We could go pick some flowers right over there.

MARINA COLE: We could. Yeah, let's do that.

LAURA: Okay.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Airplane announcement: On our final approach please make sure your seat backs and trays are in their upright and locked positions.]

LAURA: As soon as I got back I went to Eric's office.

ERIC GORDON: Hey.

LAURA: Hey.

ERIC GORDON: How are you doing?

LAURA: I had all these newspaper clippings in my bag and I was ready to show him.

JAD: How were you feeling at this point?

LAURA: I was feeling a little nervous.

LAURA: Yeah. Some of it is kind of sad and I—I just want to make sure that you're ready for that. It's not necessarily positive enlightenment about her family. So let me get it out.

LAURA: As I'm taking the stuff out of my backpack, he stops me right before I hand it to him.

ERIC GORDON: There's a part of me that's not sure I want to see it. Yeah, I think if there's no one that would receive these artifacts ultimately or that would have some sort of connection and appreciation to them, I'm not sure I want to see it.

LAURA: You don't want to know any of it?

ERIC GORDON: I don't. If there's no one to take them over, I want to live with them as a mystery.

LAURA: I couldn't blame Eric. I was even a little bit jealous of him at that point because he got to choose whether or not to look at this stuff.

JAD: So what then?

LAURA: I went home. But as soon as I got home, there was a message on my answering machine.

[ANSWERING MACHINE: Hi, this message is for Laura. My name is Bob, grandson of Ella Chase. And you called and left a message for me to try and get a hold of you regarding some pictures and letters and stuff that was found along the roadside. I think I can help fill in the pieces to the puzzle because they probably came out of my truck on the way from San Jose to Southern California.]

LAURA: I have some pretty big news for you.

ERIC: Okay.

LAURA: As soon as I got home after I talked to you on Friday, I got a message from Ella's grandson. He's the one who dropped the box.

ERIC GORDON: What?

ROBERT LYELY: It was during the course of driving down Highway 101, taking these boxes home in the back of my pickup that several of them blew out.

LAURA: And he tried to pull over and get it.

ROBERT LYELY: And I stopped alongside the road, and my wife was with me, and we picked up everything we could see.

LAURA: But as soon as he started to collect it, the California Highway Patrol pulled over and told them that he had to keep going.

ROBERT LYELY: They were gonna give me a ticket for littering.

LAURA: Because the stuff scattered everywhere.

ROBERT LYELY: Because the stuff was just blowing everywhere.

LAURA: And he has a whole bunch of boxes like the one that fell off.

ROBERT LYELY: I'm still going through the stuff, and it's been 12, 13 years now.

ERIC GORDON: I love that you actually found who dropped this stuff. And did he sound sad about it? What was his reaction?

LAURA: He just seemed happy-go-lucky about it. He was like "I think I can solve your mystery."

LAURA: When I was talking to Bob, I told him about Eric, of course, and I told him how much Eric cared about all this stuff. And he was really relieved. He didn't think it was weird at all. He just was glad that someone had cherished this stuff, and he came up with the idea right away of sending Eric kind of a replacement.

ROBERT LYELY: I have a—another group of pictures ...

LAURA: Eric sent Bob all of Ella's stuff. Bob sent Eric this mystery box full of photos that he couldn't explain.

JAD: I still can't get over the timing, though. Like, okay, so Bob passes by in the truck, the box flies out, and then what? Like, a couple hours later this goat jumps on a cow's back and causes these two people to stop and get the letters?

LAURA: Basically.

JAD: Do you think the goat on a cow was a sign?

LAURA: [laughs] What do you mean?

JAD: From Zeus? Saying "Stop. Eric, stop!"

LAURA: I think you could tell it that way, but goats like to stand on top of cows.

JAD: Really?

LAURA: Yeah. Goats like to stand on top of anything high.

JAD: [laughs]

LAURA: If there's a fence they'll jump on top of it. If there's a house they'll try and climb it. That's what goats do. Don't you think so?

JAD: [laughs] How do you know all of this?

LAURA: I've seen goats, you know? My mom used to send me up the road to buy eggs from this woman who had all these goats. And they had a little goat shack, and all the goats would be clustered on top of the goat shack, although they had a whole yard full of scraggly grass to graze in.

JAD: Did you ever say to Eric, "Um, Eric? Goats just kind of like to do this?"

LAURA: Well, no. I never said that to him. I mean, okay, goats like to stand on tall things, but since when does a cow not care? The goat's not extraordinary, it's the cow.

JAD: It's the nonchalant cow.

LAURA: Yes.

JAD: Hmm.

JAD: Laura Starecheski is a producer. She lives in New York.

ROBERT: A nonchalant cow? [laughs] Well, I hope you'll stay with us. Our next detective story begins with a drop of blood, and from the blood we discover 16.5-million baby boys.

JAD: This is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad. Robert Krulwich and I will continue in a moment.

JAD: This is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: And I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Today on our program: stories about stumbling onto the past and finding surprises, strange things. Which brings us to DNA. DNA is used to track crimes, this we know from police dramas like CSI. Far less glamorously, but no less interestingly, historians and geneticists use DNA to go way back in time and answer basic questions about who we are and where we came from. And that is an unlikely development if you think about it.

ROBERT: Yeah, because usually when—you know, if someone has sex with someone else, the DNA gets mixed. So the DNA is always changing from one generation to the next.

JAD: And if it's always getting jumbled up, one would think it would be hard to keep track of across time.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: But—and here's what you need to know for our next segment—there are patches of DNA which don't change. The Y chromosome is one of these places. This is the chromosome that men have that women don't have.

ROBERT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: And when a father has a son, he gives his son an exact copy of his Y chromosome, sort of like a Xerox machine. Then when, many years later, the boy has a boy of his own, same thing happens, an exact copy of the Y. On and on and on down the male line. Now here's where it gets interesting. Every so often, the cellular Xerox makes a mistake, a tiny mistake. Sort of like at work when you, you know, put the paper on the copier and the copy it spits back out at you has a little smudge on it, a little speck. Maybe some dust got in there, who knows? It's not a big deal. I mean, you can still read the text, but this new smudgy copy is, in its way, unique. It's no longer just a copy because it's got that speck on it.

ROBERT: Uh-huh.

JAD: This is where the analogy breaks down a bit, granted, because a paper with a speck is not a very interesting thing, but a Y chromosome with a mutation is useful because geneticists can look at that little speck, that little mutation on the Y and say, "That right there, that came from one man somewhere in time." It's a clue. And since they know that little mutation will get copied and copied and copied, they know that everyone else who shows up with it is descended from that man.

ROBERT: Now this principle, that a particular mutation on the Y chromosome comes from an individual back in time, brings us to a story that I want to tell you. Once upon a time, a group of scientists led by this guy ...

SPENCER WELLS: Yeah, I am Spencer Wells. I'm a population geneticist.

ROBERT: ... got into a Land Rover and headed off to Asia on what they call a blood sampling tour.

SPENCER WELLS: We set off in April of 1998 on a six-month odyssey, and it was literally four guys.

ROBERT: It wasn't just four guys.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Ah, so my name is Tatiana Zerjal, I'm an Italian researcher.

SPENCER WELLS: Yeah, she flew over for about three weeks.

TATIANA ZERJAL: I joined them in Tashkent.

SPENCER WELLS: She came with us to Kyrgyzstan.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Uzbekistan.

SPENCER WELLES: Taking samples in the Caucasus.

TATIANA ZERJAL: In the mountains.

SPENCER WELLES: The Altai Mountains.

ROBERT: Driving all over central Asia.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Spending 10 hours in the car.

SPENCER WELLES: We're going from place to place.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Sleeping, like, in tents.

SPENCER WELLS: And we sampled about a thousand people.

TATIANA ZERJAL: It was—it was really an adventure.

ROBERT: So here's what they'd do: each village they'd come to, they'd find out who was in charge and then they'd sit down with him or her ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: Describe the project in simple terms.

SPENCER WELLS: Basically make sure that we had permission to do the sampling.

ROBERT: It's kind of an intimate thing they're asking for here, so they'd have to do a little wooing. Usually a beverage was served, not alcohol, not coffee.

TATIANA ZERJAL: A kind of milk that comes from horses, but is a fermented milk. I couldn't spit it out because they were offering it to me and they were all smiling, so I really kind of swallow it and went away before [laughs] feeling sick.

ROBERT: So over this milky concoction they'd say to the chief, "Okay, we're here to tell your story, the history of your people, your family. Because by looking closely at the DNA in an ordinary blood sample, we can discover where your ancestors came from, where they went, who they conquered, who conquered them. We can go back hundreds of generations."

SPENCER WELLS: And typically most people would willingly give us blood samples.

JAD: Well, what were they looking for, exactly? Or I guess, what were they—what did they expect to find?

ROBERT: Well, this same group had done this in Europe, and when they did it in Europe, when they took blood from people, they found lots and lots of very distinct, separate families with very separate ancestors.

JAD: That makes sense.

ROBERT: That's what they were expecting to find in Asia. But that's not what they found. In any case, Spencer gives Tatiana a batch of the DNA samples.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Almost 2,000 samples.

ROBERT: She goes back to her lab in London.

SPENCER WELLS: And the goal again was—was very kind of open ended, what are the genetic patterns in Central Asia?

ROBERT: Tatiana gets all her DNA, lays it out and begins to investigate. And right away something's a little odd.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Very, very odd. I really thought to have made a mistake.

ROBERT: In sample after sample after sample, she could see a specific mutation.

The TATIANA ZERJAL: And we knew that everybody that present that mutation come from one individual sometimes in the past.

ROBERT: Meaning all those modern Asian guys from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and Mongolia and China, people who came from very different ancient tribes and should have only the most distant family connections, weirdly they shared a fairly recent great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandparent. No one had ever seen anything like this before.

TATIANA ZERJAL: No, never.

ROBERT: She asked for her boss to come in.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: I'm Chris Tyler-Smith.

ROBERT: And she showed him the data.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: As soon as we saw that we knew that that couldn't happen by chance alone.

ROBERT: So the first thing that she wanted to know was when did this mysterious person, when did he live?

TATIANA ZERJAL: So using some statistical programs ...

ROBERT: She plugged some data into a computer program and asked it to count backwards to the first moment when the mutation appeared.

TATIANA ZERJAL: And the program is saying roughly 1,000 years.

ROBERT: 1,000 years ago, give or take 200 years, this person lived. Now that—now this is interesting. If you were alive 1,000 years ago and you had a son and that son had a son and so forth, you would have right now about 800 living descendents. This person, whoever he was, has right now ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: Like, 16,000,000 of men.

ROBERT: 16,000,000 descendents.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Yeah, it's a lot. [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs] Yes.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: Yes, absolutely.

ROBERT: Now here's where it gets interesting. Tatiana ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: I ...

ROBERT: ... got herself a map.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Yeah, I had the map of the region, and I spread on the map the frequency of this lineage.

ROBERT: She began putting pins wherever she saw heavy concentrations of the mutation.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Mongolia.

ROBERT: She put a pin in Mongolia.

TATIANA ZERJAL: China.

ROBERT: China.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Siberia.

ROBERT: Siberia.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Kazakhstan.

ROBERT: Kazakhstan.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Pakistan.

ROBERT: And then she stood back and looked at this map. These pins spread all across Asia and she thought, "Now wait a second ..."

TATIANA ZERJAL: So then yeah, I realized that the spread of this lineage was perfectly matching the spread of the Mongol Empire.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: As soon as she saw it ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: I went to Chris and ...

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: ... Tatiana said ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: I said to him, "You know, Chris, I think I found ..."

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: Genghis Khan.

TATIANA ZERJAL: "Genghis Khan."

ROBERT: Genghis Khan. Now that's pretty interesting.

TATIANA ZERJAL: I knew just what I—I study when I was at high school, so I didn't really know much about it.

ROBERT: But she knew the basics. In the 13th century, Genghis Khan united the tribes of Mongolia into a massive army and they rode west ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: Literally killing thousands and thousands of men, so that means removing competitors. If you kill a man you kill in a sense a chromosomal lineage.

ROBERT: And then with all those men and their Y chromosomes out of the way, Genghis forced himself, I mean this is—he's the conqueror, so this is what he gets. The women having no choice in the matter because that was his privilege in those days.

TATIANA ZERJAL: He was the one picking out the youngest women and keeping them for himself.

MORRIS ROSSABI: Genghis undoubtedly had a number of—quite a number of sexual partners.

ROBERT: We wanted to just be a little careful here, so we called up an expert.

MORRIS ROSSABI: Yeah, my name is Morris Rossabi.

ROBERT: A professor of Mongolian history from Columbia University and arranged for breakfast ...

ROBERT: Can I get a couple of scrambled eggs?

WAITER: Yes.

ROBERT: I have read accounts, and I don't know how real they are, where the Mongols would come in, conquer a territory and there was a save the pretty ones for the boss kind of rule. Is that true at all?

MORRIS ROSSABI: Yes, that's true. One story is that he was murdered by one of these women he had sex with, that she placed a knife in her vagina, and as they were having sex he was stabbed and killed. Whether that's true or not [laughs] that's an interesting story.

ROBERT: Whatever. If Genghis did have the power to command any woman he wanted, and if the dates were right for history and the places were right geographically, all the evidence points in the same direction.

SPENCER WELLS: If it looks like a duck and it walks like a duck, you know, the inference was that it was a duck. This was Genghis Khan's Y chromosome lineage.

ROBERT: And so 23 scientists from all over the world together announced in the American Journal of Human Genetics that Genghis Khan was very probably the most successful biological father in human history.

JAD: In human history?

ROBERT: Yes, which ...

JAD: In all of time?

ROBERT: In all of time. And the thing about this story is it really, really—it caught people's attention. Because this is one of those things where you can actually do something about it. You can take—you know those DNA tests?

JAD: Yes, I know the DNA tests, the swab your own cheeks, put it in a vial, send it back to these companies.

ROBERT: And they send you—they could tell you whether you have Genghis Khan's marker.

JAD: How much are these tests?

ROBERT: How much? About—not mu—well, I don't know, it depends. 300 bucks?

JAD: 300?

ROBERT: 300 bucks.

JAD: 300. That's it?

ROBERT: That's it. So ...

JAD: For 300 bucks I can find out I'm related to Genghis Khan?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: I bet I am.

ROBERT: [laughs] I bet you're not!

JAD: 'Cause his conquest routes ended sort of near Lebanon where my—where my folks are from. [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs] I mean come on, look, it's suckers like you who are perfect marks for businesses like this. We found this restaurant in London ...

WAITER: Hello, welcome to Shish, how are you this evening?

ROBERT: Called Shish.

JAD: Called–called what? Shish?

ROBERT: Yeah, Shish, because for—short for Shish Kabob. They announced a major Genghis Khan promotion.

WAITER: Ten winners had DNA testing done in Oxford to find out if they were ancestors of Genghis Khan. This was very unique, and the response was just ...

ROBERT: People came and came.

WAITER: ... immense.

ROBERT: There were lines around the block.

WAITER: ... phone call. The phones were ringing all day, I mean I had never thought there would have been that interest.

ROBERT: You see, you weren't the only one. There were a lot of people working under strange illusions like you.

JAD: [laughs] Let me ask you this though: if I—let's say I had taken the test and it came up positive I am, so it seems related to Genghis Khan, does that really mean anything definitively? I mean, is that marker for sure Genghis Khan's marker? Do we know that?

ROBERT: In fact, no. The only way you ever know for sure that it's anybody's mutation is you gotta go to the body ...

JAD: Mm-hmm.

ROBERT: ... pluck some DNA from the body, see if it matches the mutation. So you gotta find Genghis Khan's body.

SPENCER WELLS: Yeah, that would be the ultimate proof.

ROBERT: And, by the way, there's a lot of people looking.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Oh my God. Oh. I found a human skull, buried in the ground.]

MAURY KRAVITZ: I have been doing this now for going on to eight and a half years, and we've dug up some very nice fellas so far.

ROBERT: That guy is Maury Kravitz.

MAURY KRAVITZ: This voice you hear is a direct result of screaming.

ROBERT: For years he was a commodities trader in Chicago.

MAURY KRAVITZ: Yeah, I was a warrior of the trading pits.

ROBERT: He got just enough money—actually, he made quite a bit of money—to sponsor annual summer trips looking for Genghis Khan's corpse.

JAD: Why is he looking for Genghis Khan?

MAURY KRAVITZ: Valuables. Great wealth.

ROBERT: Because he knows for all the sacking and pillaging that the Mongols did back in the 1200s ...

MAURY KRAVITZ: To this day, not one bejeweled dagger, not one necklace, not one diamond-studded tiara which could be identified from the 13th century has ever surfaced.

ROBERT: Suggesting that it might be all under the surface of the ground somewhere?

MAURY KRAVITZ: Suggesting that it all went south with the old man.

ROBERT: So there might be two treasures here, there's the physical treasure and the biological treasure.

MAURY KRAVITZ: Well, that's for the scientists. I am a different sort of Genghis Khan man. But they're not gonna be able to do a proper DNA search unless a guy like me finds the tomb.

ROBERT: Maury says if there is a treasure, he will happily hand it over to the Mongolian government, but the officials are a little leery.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Excavation ...]

ROBERT: So he continues to plead his case.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Can we excavate or can't we excavate? What do you mean, no?]

ROBERT: And he keeps digging up bodies, always with the same result.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Well, it's not Genghis Khan. It's not Genghis Khan.]

ROBERT: The problem is nobody knows where Genghis Khan is buried. They don't even know if he was buried. They don't know if there's any place or thing to find.

MORRIS ROSSABI: It appears unlikely.

ROBERT: Professor Rossabi says ...

MORRIS ROSSABI: No.

ROBERT: ... Looking for Genghis is an—I don't know.

MORRIS ROSSABI: He died in 1227, and they had no tradition of tomb culture at that point. The body was just left where it lay.

JAD: So does that mean that we'll never know?

ROBERT: Well, there may be a way out of this. Genghis Khan, he had a grandson, Kublai Khan, the famous emperor of China. Kublai has the same exact mutation that his grandpa had, that's the nature of this.

MORRIS ROSSABI: And I think the more likely discovery will be of Kublai Khan's tomb.

ROBERT: Why not look for Kublai?

ROBERT: Where is Kublai Khan's body, would you guess?

MORRIS ROSSABI: Well, we know. It's stated in the sources that it's somewhere in inner Mongolia. When it is discovered it will be a real bonanza.

ROBERT: So have you talked to Maury ever? I mean—it seems to me you could get on the phone and say, "You idiot, you're looking for the wrong guy?"

MORRIS ROSSABI: [laughs] Well I—I ...

MAURY KRAVITZ: Wait, I'm going to cut you off. Morris Rossabi is going to say I'm looking for the wrong guy?

ROBERT: You know it's true, he happens to—Kublai Khan is his—is his pick.

MAURY KRAVITZ: It's his pick because he wrote a book on Kublai Khan. [laughs]

ROBERT: Okay, okay. The point is both him and Kublai Khan both have the same genetic marker, so if you find either one—either one will do. Pluck a hair from either guy's body, look at the DNA, and then you will know for sure if Genghis and his family not only conquered the ancient world, but fathered the modern world. One day we will know. And I guess the neat thing about all of these tales is, you know, you think when you're gonna tell a story from the past that the sensible place to go is you go to the library, you go to a fossil, you go to a ruin, but the truth is you can go anywhere. The blood coursing through your veins tells you I have a story for you. Same with a little bit of garbage that sits next to an ancient shoe, you pluck the piece of paper and Jesus is talking to you—literally! There are clues about the past everywhere, and if it's a knock on your door and you decide to open the door and take a look, who knows what you will find and who knows where you will go.

JAD: By the way, the video clip used in that last segment was provided courtesy of A&E Networks. And for more information on anything you heard this hour, visit our website, Radiolab.org.

ROBERT: And communicate it with us while you're there, it's—here's our address.

JAD: Radiolab (@) wnyc.org is our email address. I'm Jad Abumrad. Robert Krulwich and I are signing off.

ROBERT: Thanks for listening.

[TATIANA ZERJAL: Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad and Ellen Horne, with help from Sarah Pellegrini, Melissa Kegel, Lulu Miller, Amber Cille. Cille, how do you pronounce that one? Amber Cille, Casey Edwards and Jed Paris. And special thanks to Sally Herships, he New York Department of Sanitation and Chief Diggins, Nicapolo Dice, Marina Cole, and to me Tatiana Zerjal. [laughs] Yeah. Production management by Michael Alsessar and Dean Capello. Radiolab is produced by WNYC, New York Public Radio. Bye-bye.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.