Aug 19, 2010

Transcript

ELLEN HORNE: Do you want to get out?

JAD ABUMRAD: Is this—is this us?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah, this is us.

JAD: Okay.

JAD: This is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad. Since our program today deals with stumbling upon the past in unlikely places, we thought we'd begin this part of the show well, not at a place we'd normally visit.

JAD: So I feel like we're standing on top of a mountain, but how high up are we?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Right here I believe we're about 180.

JAD: This, by the way, is Chief Dennis Diggins.

DENNIS DIGGINS: I'm an assistant chief in the New York City Department of Sanitation.

JAD: And when he says 180 he means feet.

DENNIS DIGGINS: About 180 feet high.

JAD: Wow, so that's about 18 stories.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Correct.

JAD: 18 stories up into the Staten Island sky, that's where we're standing.

JAD: Where we're standing.

JAD: On a hill.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Basically like a big dirt hill.

JAD: And at a glance, you would never know that this hill was made from anything other than dirt.

JAD: What did this used to be?

JAD: Unless, of course, you dug about a few feet down.

DENNIS DIGGINS: This is all garbage underneath us. Up until March of 2001, we were taking in all of New York City's garbage.

JAD: All the boroughs were coming here?

DENNIS DIGGINS: All the boroughs were coming here. So we were probably taking in on average 11,000 tons a day.

JAD: 11,000 tons a day. That's—what does 11,000 tons look like?

DENNIS DIGGINS: [laughs] It's a lot of garbage.

JAD: Fresh Kills used to be the biggest dump on the planet. But that's all in the past. With a little engineering help ...

DENNIS DIGGINS: It's gonna be a great park. Absolutely.

JAD: ... this will be a park.

DENNIS DIGGINS: I mean, just look at how much property you have. You take ...

JAD: All these mounds are getting wrapped in plastic and covered with grass. There will be a restaurant ...

JAD: I can almost imagine that.

JAD: ... even a golf course.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah, I would love to be the first one to tee off on that.

JAD: [laughs]

JAD: But underneath it all, the garbage will still be here. 50 years of trash, waiting patiently until someone comes to look for it—and someone always does.

DENNIS DIGGINS: I know years ago we—there was a—a garb—an arch—how do I say it right? An archeological garbageman that came here and he did some core sampling.

JAD: Meaning with a special tool, this guy bored a hole deep into the center of the mound.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Actually came up with a—a hot dog. Landfilled 10 years previously.

JAD: Are you kidding me?

DENNIS DIGGINS: So ... [laughs]

JAD: Hot dog that was 10 years old and was still a hot dog?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah it was still a hot dog.

JAD: Recognizably a hot dog?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Yeah, recognizably a hot dog. So that's ...

JAD: That's amazing and disgusting.

DENNIS DIGGINS: [laughs] I still like hot dogs so I'll eat them, but ...

JAD: No, but seriously, do you ever consider the history that's contained in this—in this big chunk of garbage?

DENNIS DIGGINS: Oh, yeah. Well, this is one big time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time capsule. Time cap ...

JAD: You can stop—stop saying that now. Thank you. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab, a series about science and discovery. And that is exactly what we have for you today: three detective stories.

ROBERT: And each one begins with a rather peculiar clue.

JAD: Clues that lead you back into the past.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

DENNIS DIGGINS: Time capsule.

JAD: And now that we've got that phrase in our minds, and garbage as well, let's go to a different part of the world and get things started for real, to a different time also. 1898, Egypt. Oxyrhynchus Egypt. You with me?

ROBERT: Where is Oxyrhynchus Egypt?

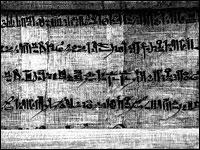

JAD: It's in the south, in the desert. South of—of Cairo, I think, and it—and let me show you a picture.

ROBERT: All right.

JAD: You see the desert?

ROBERT: Oh yeah. It's a big flat sort of sandy place, and these—who is this guy?

JAD: Well, you should see two guys, they are—they're two Oxford archeologists.

ROBERT: Yeah with a pith helmet, and sort of standing high on a mound, looking down.

JAD: Yeah, one guy is on top of the mound, the other guy is towards the bottom. That's Grenfell and Hunt, two Oxford archeologists. They were in Egypt in 1898 looking for treasure and they find those sand dunes.

ROBERT: Mm-hmm. Which don't look quite like the other sand dunes, really. They're sort of ...

JAD: Yeah they're sort of—sort of strange, and irregularly shaped. Which is why when they saw those sand dunes that you're looking at, they hired a team of workers and they started to dig. And they immediately began to find things.

DIRK OBBINK: Huge quantity of pottery, clothes, shoes, baskets, rope.

JAD: That's Dirk Obbink, a scholar from Oxford. He tells the story of what they found, and what they found was basically ...

DIRK OBBINK: The motherlode. A huge circle of rubbish mounds, over 20 of them that were completely undisturbed.

JAD: This was no piddly little trash heap that was 50 years old like you might find in Staten Island. These mounds were really old.

DIRK OBBINK: These were rubbish mounds that had built up over the course of 10 centuries.

JAD: 10 centuries of trash.

ROBERT: [gasps] That's 1,000 years of trash. [laughs]

JAD: Yeah, and that included a lot of ancient paper. That's what they were really interested in. Any scraps or scrolls they could find.

DIRK OBBINK: And one of the first ones that they pulled out of the ground was Lost Sayings of Jesus.

JAD: What?

DIRK OBBINK: That was the first one that they pulled out of the ground.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: He who knows the all but fails to know himself lacks everything. If they say to you whence have you come ...]

JAD: Okay, forget the 10-year-old hot dog. Here we have sayings of Jesus which have not been seen, read or even heard about for almost 2,000 years.

DIRK OBBINK: A long list of sayings that are not in the canonical books of the Bible.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: He who seeks let him not cease seeking until he finds ...]

JAD: This is a different Jesus than the one in the Bible. It's almost Eastern in tone, he says, "Heaven is here."

[ARCHIVE CLIP: The kingdom of the father is spread out upon the Earth.]

JAD: It's all around us.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: And men do not see it.]

JAD: If we just opened our eyes.

DIRK OBBINK: It's a papyrus that today is known as the Logia Fragment.

JAD: And there it was buried in the trash.

ROBERT: Wow!

JAD: Anyhow, the team pulled as much paper as they could from the mounds, separated out all the shoes and stuff and just took the paper.

DIRK OBBINK: And then they packed those up with hundreds of boxes, and shipped them back here to Oxford.

DIRK OBBINK: This is the Sackwood library in Oxford, and we're still today, 107 years later ...

DIRK OBBINK: We're—we're going upstairs now.

DIRK OBBINK: ... we're still today opening those boxes, pulling out the fragments, piecing them back together and deciphering them.

JAD: This is what 2,000-year-old paper sounds like. Sounds just like paper, and it looks like dried leaves. Not really much to look at or listen to, but knowing that it's 2,000 years old and theoretically could've been written on by Jesus himself? Well, it makes it a little more special, which is why we visited Oxford, England, where the dump now lives, packed away in 700 boxes.

NICK GIANNIS: This is a box that contains about 600 unpublished papyri.

JAD: Nick Giannis, one of the collections curators popped one open for us.

NICK GIANNIS: I'm just opening an official document sometime early in the fourth century. Of course, it's full of—of holes, probably caused by little worms.

JAD: And there's the sad part: there are enough secrets in the boxes to rewrite the past. The problem is ...

NICK GIANNIS: Much of this is hopelessly fragmented.

JAD: ... reading it is almost impossible.

NICK GIANNIS: Some of the smaller fragments if you see lots of them, it looks like a conglomeration of corn flakes. It will be a few hundred years before even the most substantial of these fragments come to light.

DIRK OBBINK: We're talking about the reconstruction of works that—the work on which is beyond the scale of a single human lifetime.

JAD: Way beyond. In the past 107 years, the Oxford team has worked their way through a whopping one percent of the collection. It may take another 10 centuries to get through the rest. Here's how it usually goes: Nick scours the boxes each day, finds a new scrap, tiny little scrap, and brings it into the lab for cleaning.

DIRK OBBINK: What I do now is I remove some ancient mud with the help of a brush.

JAD: Here he wipes ancient mud from a torn page of Homer's Iliad. After it's mud free, each piece is cataloged in the computer.

DIRK OBBINK: For various features like type of handwriting, size and style.

JAD: And if the piece seems to match another pieces, Dirk and maybe a grad student spread them all out on a long wooden table and basically from there it's a classic jigsaw puzzle.

DIRK OBBINK: How about this one? Doesn't it look like these might be the line beginnings of ...

JAD: They move one here.

NICK GIANNIS: I think that—that looks like a promising match.

JAD: See if the words match up.

DIRK OBBINK: Because they seem to line up pretty exactly with the lines of the larger fragment.

JAD: May take five minutes, may take five years, may take five lifetimes. But eventually they will have—well, not the whole story. Not even a page of the whole story. But something.

NICK GIANNIS: I've put the papyrus under a—an electronic microscope.

JAD: Maybe just a few Greek words from the deep past.

NICK GIANNIS: [speaking Greek]

DIRK OBBINK: [speaking Greek]

NICK GIANNIS: But we're missing a bit from the upper right corner.

DIRK OBBINK: Sometimes a sentence breaks off just when you need it to tell you what you need to know. We have to be satisfied with knowing a little rather than a lot.

ROBERT: Let me make sure I understand this. Is each of these fragments just a teeny—like is it "To be, or?"

JAD: It's more like, "To."

ROBERT: [laughs] Oh, it's that small?

JAD: Some of them are tiny. Tiny. I mean, there's about a half a million in total.

ROBERT: Half a million!

JAD: And—and they've only got through about 5,000.

ROBERT: Well is—do you have in your own list of things like a sort of favorite hits list?

JAD: I do. I do. I've narrowed it down to my top three.

ROBERT: Oh, okay!

JAD: My top three ancient garbage greatest hits, if you will. Which was difficult, but here are three that are really interesting.

ROBERT: First, number three!

JAD: Ancient Garbage Greatest Hits number three. You, being a death metal fan, I'm sure are familiar with these three inauspicious numbers.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Iron Maiden "Number of the Beast": 666, the number of the beast. 666, the number of the beast. Yeah!]

ROBERT: Absolutely! 666, sign of the beast.

JAD: Right. Just to explain: the number of the beast, 666, is what you use to either summon the beast or keep the beast away because you can't say his name directly. That would be bad. All this comes from the New Testament.

DIRK OBBINK: Okay.

JAD: Dirk showed me a piece of papyrus that he found in the dump. It's about the size of your palm.

JAD: So what are we looking at? This looks like this may be 30 letters.

JAD: A copy of precisely that passage in the New Testament where the number is stated.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Vincent Price: Let him who hath understanding reckon the number of the beast. For it is a human number. Its number is six hundred and sixty six.]

DIRK OBBINK: 666, which was the traditional number of the beast.

JAD: Now here's the thing: this little scrap of papyrus that Dirk turned up is the earliest known copy that we have of that passage. He showed me ...

JAD: But can you—can you point to the letters again and show me ...

JAD: ... its three numbers are smack in the center of the papyrus.

Dirk Obbink: Three Greek letters: Chi, Iota and Sigma.

JAD: Chi, Iota, Sigma.

ROBERT: Chi, Iota, Sigma.

JAD: Should say 666, right?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: But, in fact, Chi, Iota, Sigma don't say 666.

ROBERT: They don't? What do they say?

JAD: 6 ...

DIRK OBBINK: 616.

JAD: ... 16.

ROBERT: No!

DIRK OBBINK: Instead of 666.

ROBERT: Really?

JAD: Yeah!

ROBERT: Does that mean all the bibles are wrong, or ...

JAD: Maybe. I mean, all we really know is that the number of the beast had versions.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: And that 616 may be the original.

ROBERT: Oh!

JAD: How long does it take this to filter into the King James Bible or something like that?

DIRK OBBINK: Oh no, it will appear in the next standard edition of the New Testament in a note on that page representing it as a viable variant that has now appeared in a papyrus text.

ROBERT: What—what—do biblical scholars accept this?

JAD: They do.

ROBERT: Oh so you should just probably be very careful about six blank six for the—if you are worrying about the beast.

JAD: Well you should probably change your tattoo. [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs] Shhh!

JAD: Okay. Let's move on to number two. Garbage Greatest Hits number two.

JAD: Hey, did you see the movie Troy?

ROBERT: Yes.

JAD: You remember this scene?

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Troy: "Hector!"]

ROBERT: Big, bold, muscular men fighting big, bold, muscular fights with big, bold, muscular enemies.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Troy: "Hector!"]

ROBERT: I know the film, and I know how big, bold and muscular it was.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Troy: "Hector!"]

ROBERT: What did your scrap tell you?

JAD: Well, the papyri folks recently—this is big news in the world of the papyrologists, they got their hands on this special camera.

PAPYROLOGIST: So we have this digital setup here, a camera on a—on a sort of easel.

JAD: This camera uses infrared filters to photograph text that's so faded that you can't really see it with the naked eye.

PAPYROLOGIST: Take a—quite a long exposure.

JAD: In any case, the first thing they read with that camera is a poem about the Trojan War.

DIRK OBBINK: The new poem of—of Archilochus.

JAD: This poem.

DIRK OBBINK: [speaking Greek]

JAD: Comes from the 600s.

ROBERT: Oh, it's not Homer, it's Archilochus's version.

JAD: No, it's precisely not Homer because whereas the Homeric version, the Brad Pitt version, it goes, you know: Greeks invade, Troy falls, hoorah. This version goes: Greeks invade, get their butts kicked, then run. Run like sissies.

ROBERT: Oh! [laughs]

DIRK OBBINK: So it completely turns the Homeric account on its head.

ROBERT: Wait, wait, wait, wait. So this—this was written at the same time as Homer?

JAD: A little bit later, but in response to Homer.

ROBERT: Oh!

DIRK OBBINK: And the Greek goes like this.

JAD: Here, listen.

DIRK OBBINK: [reading Greek version] "One doesn't have to call it weakness and cowardice having to retreat. No, there does exist a proper time for flight."

JAD: See, Homer's notion was, like, that the hero stands and fights to the end, but this poet was saying, "You know what?"

DIRK OBBINK: No ...

JAD: "We ran away."

DIRK OBBINK: We turned our backs to flee quickly.

JAD: "And that's okay."

DIRK OBBINK: He actually celebrated it as something that he was proud of because sometimes you had to turn and run.

ROBERT: Running away is a good thing.

JAD: Running away is a good thing.

ROBERT: That's a good one.

JAD: See, what's interesting about the past you find in the trash is that it's messy, it's complicated. There's not just the story you know, there's contradictions to that story, competing accounts of that story, which can be disconcerting. I mean, you know, who wants to have different bibles floating around? That could be weird for people. But to me, to know that way back when, even then there were different ideas about what it means to be a hero? That I find comforting. Which brings us to my first choice.

ROBERT: And last but hardly least.

JAD: Ancient Garbage Greatest Hit number—well the greatest hit. What do you think people in the first century were reading?

ROBERT KRULWICH: What do I think they were reading?

JAD: Mm-hmm. What do you think they were really reading?

DIRK OBBINK: Okay when the—when the text starts she's saying, "Oh, I'm terribly on fire." And that goes in Greek [reading Greek] The translation: "Uh oh, it's thick and big as a roof beam."

ROBERT: [laughs]

DIRK OBBINK: And then she goes on. "Manai, cat of ..."

JAD: Porn, that's what they were reading. This filthy satire turned up enough times in this and other dumps for Dirk to suspect that they may have been a bestseller.

ROBERT: So there was more than one version of this?

JAD: It appeared over and over and over.

DIRK OBBINK: "I'm burning, I'm on fire, I'm terribly on fire. A stream runs over me. Do you understand?"

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.