Aug 19, 2010

Transcript

JAD: This is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: And I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Today on our program: stories about stumbling onto the past and finding surprises, strange things. Which brings us to DNA. DNA is used to track crimes, this we know from police dramas like CSI. Far less glamorously, but no less interestingly, historians and geneticists use DNA to go way back in time and answer basic questions about who we are and where we came from. And that is an unlikely development if you think about it.

ROBERT: Yeah, because usually when—you know, if someone has sex with someone else, the DNA gets mixed. So the DNA is always changing from one generation to the next.

JAD: And if it's always getting jumbled up, one would think it would be hard to keep track of across time.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: But—and here's what you need to know for our next segment—there are patches of DNA which don't change. The Y chromosome is one of these places. This is the chromosome that men have that women don't have.

ROBERT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: And when a father has a son, he gives his son an exact copy of his Y chromosome, sort of like a Xerox machine. Then when, many years later, the boy has a boy of his own, same thing happens, an exact copy of the Y. On and on and on down the male line. Now here's where it gets interesting. Every so often, the cellular Xerox makes a mistake, a tiny mistake. Sort of like at work when you, you know, put the paper on the copier and the copy it spits back out at you has a little smudge on it, a little speck. Maybe some dust got in there, who knows? It's not a big deal. I mean, you can still read the text, but this new smudgy copy is, in its way, unique. It's no longer just a copy because it's got that speck on it.

ROBERT: Uh-huh.

JAD: This is where the analogy breaks down a bit, granted, because a paper with a speck is not a very interesting thing, but a Y chromosome with a mutation is useful because geneticists can look at that little speck, that little mutation on the Y and say, "That right there, that came from one man somewhere in time." It's a clue. And since they know that little mutation will get copied and copied and copied, they know that everyone else who shows up with it is descended from that man.

ROBERT: Now this principle, that a particular mutation on the Y chromosome comes from an individual back in time, brings us to a story that I want to tell you. Once upon a time, a group of scientists led by this guy ...

SPENCER WELLS: Yeah, I am Spencer Wells. I'm a population geneticist.

ROBERT: ... got into a Land Rover and headed off to Asia on what they call a blood sampling tour.

SPENCER WELLS: We set off in April of 1998 on a six-month odyssey, and it was literally four guys.

ROBERT: It wasn't just four guys.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Ah, so my name is Tatiana Zerjal, I'm an Italian researcher.

SPENCER WELLS: Yeah, she flew over for about three weeks.

TATIANA ZERJAL: I joined them in Tashkent.

SPENCER WELLS: She came with us to Kyrgyzstan.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Uzbekistan.

SPENCER WELLES: Taking samples in the Caucasus.

TATIANA ZERJAL: In the mountains.

SPENCER WELLES: The Altai Mountains.

ROBERT: Driving all over central Asia.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Spending 10 hours in the car.

SPENCER WELLES: We're going from place to place.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Sleeping, like, in tents.

SPENCER WELLS: And we sampled about a thousand people.

TATIANA ZERJAL: It was—it was really an adventure.

ROBERT: So here's what they'd do: each village they'd come to, they'd find out who was in charge and then they'd sit down with him or her ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: Describe the project in simple terms.

SPENCER WELLS: Basically make sure that we had permission to do the sampling.

ROBERT: It's kind of an intimate thing they're asking for here, so they'd have to do a little wooing. Usually a beverage was served, not alcohol, not coffee.

TATIANA ZERJAL: A kind of milk that comes from horses, but is a fermented milk. I couldn't spit it out because they were offering it to me and they were all smiling, so I really kind of swallowed it and went away before [laughs] feeling sick.

ROBERT: So over this milky concoction they'd say to the chief, "Okay, we're here to tell your story, the history of your people, your family. Because by looking closely at the DNA in an ordinary blood sample, we can discover where your ancestors came from, where they went, who they conquered, who conquered them. And we can go back hundreds of generations."

SPENCER WELLS: And typically most people would willingly give us blood samples.

JAD: Well, what were they looking for, exactly? Or I guess, what were they—what did they expect to find?

ROBERT: Well, this same group had done this in Europe, and when they did it in Europe, when they took blood from people, they found lots and lots of very distinct, separate families with very separate ancestors.

JAD: That makes sense.

ROBERT: That's what they were expecting to find in Asia. But that's not what they found. In any case, Spencer gives Tatiana a batch of the DNA samples.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Almost 2,000 samples.

ROBERT: She goes back to her lab in London.

SPENCER WELLS: And the goal again was—was very kind of open ended, what are the genetic patterns in Central Asia?

ROBERT: Tatiana gets all her DNA, lays it out and begins to investigate. And right away something's a little odd.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Very, very odd. I really thought to have made a mistake.

ROBERT: In sample after sample after sample, she could see a specific mutation.

The TATIANA ZERJAL: And we knew that everybody that present that mutation come from one individual sometimes in the past.

ROBERT: Meaning all those modern Asian guys from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and Mongolia and China, people who came from very different ancient tribes and should have only the most distant family connections, weirdly they shared a fairly recent great, great, great, great, great, great, great grandparent. No one had ever seen anything like this before.

TATIANA ZERJAL: No, never.

ROBERT: She asked for her boss to come in.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: I'm Chris Tyler-Smith.

ROBERT: And she showed him the data.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: As soon as we saw that we knew that that couldn't happen by chance alone.

ROBERT: So the first thing that she wanted to know was when did this mysterious person, when did he live?

TATIANA ZERJAL: So using some statistical programs ...

ROBERT: She plugged some data into a computer program and asked it to count backwards to the first moment when the mutation appeared.

TATIANA ZERJAL: And the program is saying roughly 1,000 years.

ROBERT: 1,000 years ago, give or take 200 years, this person lived. Now that—now this is interesting. If you were alive 1,000 years ago and you had a son and that son had a son and so forth, you would have right now about 800 living descendents. This person, whoever he was, has right now ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: Like, 16,000,000 of men.

ROBERT: 16,000,000 descendents.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Yeah, it's a lot. [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs] Yes.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: Yes, absolutely.

ROBERT: Now here's where it gets interesting. Tatiana ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: I ...

ROBERT: ... got herself a map.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Yeah, I had the map of the region, and I spread on the map the frequency of this lineage.

ROBERT: She began putting pins wherever she saw heavy concentrations of the mutation.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Mongolia.

ROBERT: She put a pin in Mongolia.

TATIANA ZERJAL: China.

ROBERT: China.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Siberia.

ROBERT: Siberia.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Kazakhstan.

ROBERT: Kazakhstan.

TATIANA ZERJAL: Pakistan.

ROBERT: And then she stood back and looked at this map. These pins spread all across Asia and she thought, "Now wait a second ..."

TATIANA ZERJAL: So then yeah, I realized that the spread of this lineage was perfectly matching the spread of the Mongol Empire.

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: As soon as she saw it ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: I went to Chris and ...

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: ... Tatiana said ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: I said to him, "You know, Chris, I think I found ..."

CHRIS TYLER-SMITH: Genghis Khan.

TATIANA ZERJAL: "Genghis Khan."

ROBERT: Genghis Khan. Now that's pretty interesting.

TATIANA ZERJAL: I knew just what I—I study when I was at high school, so I didn't really know much about it.

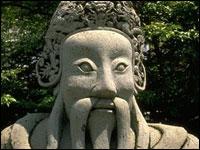

ROBERT: But she knew the basics. In the 13th century, Genghis Khan united the tribes of Mongolia into a massive army and they rode west ...

TATIANA ZERJAL: Literally killing thousands and thousands of men, so that means removing competitors. If you kill a man you kill in a sense a chromosomal lineage.

ROBERT: And then with all those men and their Y chromosomes out of the way, Genghis forced himself, I mean this is—he's the conqueror, so this is what he gets. The women having no choice in the matter because that was his privilege in those days.

TATIANA ZERJAL: He was the one picking out the youngest women and keeping them for himself.

MORRIS ROSSABI: Genghis undoubtedly had a number of—quite a number of sexual partners.

ROBERT: We wanted to just be a little careful here, so we called up an expert.

MORRIS ROSSABI: Yeah, my name is Morris Rossabi.

ROBERT: A professor of Mongolian history from Columbia University and arranged for breakfast ...

ROBERT: Can I get a couple of scrambled eggs?

WAITER: Yes.

ROBERT: I have read accounts, and I don't know how real they are, where the Mongols would come in, conquer a territory and there was a save the pretty ones for the boss kind of rule. Is that true at all?

MORRIS ROSSABI: Yes, that's true. One story is that he was murdered by one of these women he had sex with, that she placed a knife in her vagina, and as they were having sex he was stabbed and killed. Whether that's true or not [laughs] that's an interesting story.

ROBERT: Whatever. If Genghis did have the power to command any woman he wanted, and if the dates were right for history and the places were right geographically, all the evidence points in the same direction.

SPENCER WELLS: If it looks like a duck and it walks like a duck, you know, the inference was that it was a duck. This was Genghis Khan's Y chromosome lineage.

ROBERT: And so 23 scientists from all over the world together announced in the American Journal of Human Genetics that Genghis Khan was very probably the most successful biological father in human history.

JAD: In human history?

ROBERT: Yes, which ...

JAD: In all of time?

ROBERT: In all of time. And the thing about this story is it really, really—it caught people's attention. Because this is one of those things where you can actually do something about it. You can take—you know those DNA tests?

JAD: Yes, I know the DNA tests, the swab your own cheeks, put it in a vial, send it back to these companies.

ROBERT: And they send you—they could tell you whether you have Genghis Khan's marker.

JAD: How much are these tests?

ROBERT: How much? About—not mu—well, I don't know, it depends. 300 bucks?

JAD: 300?

ROBERT: 300 bucks.

JAD: 300. That's it?

ROBERT: That's it. So ...

JAD: For 300 bucks I can find out I'm related to Genghis Khan?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: I bet I am.

ROBERT: [laughs] I bet you're not!

JAD: 'Cause his conquest routes ended sort of near Lebanon where my—where my folks are from. [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs] I mean come on, look, it's suckers like you who are perfect marks for businesses like this. We found this restaurant in London ...

WAITER: Hello, welcome to Shish, how are you this evening?

ROBERT: Called Shish.

JAD: Called—called what? Shish?

ROBERT: Yeah, Shish, because for—short for Shish Kebab. They announced a major Genghis Khan promotion.

WAITER: Ten winners had DNA testing done in Oxford to find out if they were ancestors of Genghis Khan. This was very unique, and the response was just ...

ROBERT: People came and came.

WAITER: ... immense.

ROBERT: There were lines around the block.

WAITER: ... phone call. The phones were ringing all day, I mean I had never thought there would have been that interest.

ROBERT: You see, you weren't the only one. There were a lot of people working under strange illusions like you.

JAD: [laughs] Let me ask you this though: if I—let's say I had taken the test and it came up positive I am, so it seems related to Genghis Khan, does that really mean anything definitively? I mean, is that marker for sure Genghis Khan's marker? Do we know that?

ROBERT: In fact, no. The only way you ever know for sure that it's anybody's mutation is you gotta go to the body ...

JAD: Mm-hmm.

ROBERT: ... pluck some DNA from the body, see if it matches the mutation. So you gotta find Genghis Khan's body.

SPENCER WELLS: Yeah, that would be the ultimate proof.

ROBERT: And, by the way, there's a lot of people looking.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Oh my God. Oh! I found a human skull, buried in the ground.]

MAURY KRAVITZ: I have been doing this now for going on to eight and a half years, and we've dug up some very nice fellas so far.

ROBERT: That guy is Maury Kravitz.

MAURY KRAVITZ: This voice you hear is a direct result of screaming.

ROBERT: For years he was a commodities trader in Chicago.

MAURY KRAVITZ: Yeah, I was a warrior of the trading pits.

ROBERT: He got just enough money—actually, he made quite a bit of money—to sponsor annual summer trips looking for Genghis Khan's corpse.

JAD: Why is he looking for Genghis Khan?

MAURY KRAVITZ: Valuables. Great wealth.

ROBERT: Because he knows for all the sacking and pillaging that the Mongols did back in the 1200s ...

MAURY KRAVITZ: To this day, not one bejeweled dagger, not one necklace, not one diamond-studded tiara which could be identified from the 13th century has ever surfaced.

ROBERT: Suggesting that it might be all under the surface of the ground somewhere?

MAURY KRAVITZ: Suggesting that it all went south with the old man.

ROBERT: So there might be two treasures here, there's the physical treasure and the biological treasure.

MAURY KRAVITZ: Well, that's for the scientists. I am a different sort of Genghis Khan man. But they're not gonna be able to do a proper DNA search unless a guy like me finds the tomb.

ROBERT: Maury says if there is a treasure, he will happily hand it over to the Mongolian government, but the officials are a little leery.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Excavation ...]

ROBERT: So he continues to plead his case.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Can we excavate or can't we excavate? What do you mean, no?]

ROBERT: And he keeps digging up bodies, always with the same result.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Maury Kravitz: Well, it's not Genghis Khan. It's not Genghis Khan.]

ROBERT: The problem is nobody knows where Genghis Khan is buried. They don't even know if he was buried. They don't know if there's any place or thing to find.

MORRIS ROSSABI: It appears unlikely.

ROBERT: Professor Rossabi says ...

MORRIS ROSSABI: No.

ROBERT: ... Looking for Genghis is an—I don't know.

MORRIS ROSSABI: He died in 1227, and they had no tradition of tomb culture at that point. The body was just left where it lay.

JAD: So does that mean that we'll never know?

ROBERT: Well, there may be a way out of this. Genghis Khan, he had a grandson, Kublai Khan, the famous emperor of China. Kublai has the same exact mutation that his grandpa had, that's the nature of this.

MORRIS ROSSABI: And I think the more likely discovery will be of Kublai Khan's tomb.

ROBERT: Why not look for Kublai?

ROBERT: Where is Kublai Khan's body, would you guess?

MORRIS ROSSABI: Well, we know. It's stated in the sources that it's somewhere in inner Mongolia. When it is discovered it'll be a real bonanza.

ROBERT: So have you talked to Maury ever? I mean—it seems to me you could get on the phone and say, "You idiot, you're looking for the wrong guy?"

MORRIS ROSSABI: [laughs] Well I—I ...

MAURY KRAVITZ: Wait, I'm gonna cut you off. Morris Rossabi is going to say I'm looking for the wrong guy?

ROBERT: You know it's true, he happens to—Kublai Khan is his—is his pick.

MAURY KRAVITZ: It's his pick because he wrote a book on Kublai Khan. [laughs]

ROBERT: Okay, okay. The point is both him and Kublai Khan both have the same genetic marker, so if you find either one—either one will do. Pluck a hair from either guy's body, look at the DNA, and then you will know for sure if Genghis and his family not only conquered the ancient world, but fathered the modern world. One day we will know. And I guess the neat thing about all of these tales is, you know, you think when you're gonna tell a story from the past that the sensible place to go is you go to the library, you go to a fossil, you go to a ruin, but the truth is you can go anywhere. The blood coursing through your veins tells you I have a story for you. Same with a little bit of garbage that sits next to an ancient shoe, you pluck the piece of paper and Jesus is talking to you—literally! There are clues about the past everywhere, and if it's a knock on your door and you decide to open the door and take a look, who knows what you will find and who knows where you will go.

JAD: By the way, the video clip used in that last segment was provided courtesy of A&E Networks. And for more information on anything you heard this hour, visit our website, Radiolab.org.

ROBERT: And communicate it with us while you're there, it's—here's our address.

JAD: Radiolab (@) wnyc.org is our email address. I'm Jad Abumrad. Robert Krulwich and I are signing off.

ROBERT: Thanks for listening.

[TATIANA ZERJAL: Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad and Ellen Horne, with help from Sarah Pellegrini, Melissa Kegel, Lulu Miller, Amber Cille. Cille, how do you pronounce that one? Amber Cille, Casey Edwards and Jed Paris. And special thanks to Sally Herships, he New York Department of Sanitation and Chief Diggins, Nicapolo Dice, Marina Cole, and to me Tatiana Zerjal. [laughs] Yeah. Production management by Michael Alsessar and Dean Capello. Radiolab is produced by WNYC, New York Public Radio. Bye-bye.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.