Dec 15, 2008

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, man: Ladies and gentlemen, the President of the United States.]

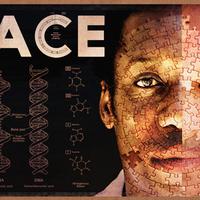

JAD ABUMRAD: June 26, 2000, 10:19 a.m., at the White House. This is the moment that race died.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Clinton: Good morning. We're here to celebrate the completion of the first survey of the entire human genome—of the entire human genome—of the entire human genome ...]

JAD: See, for a hundred years, scientists—or at least a certain group of scientists—had been trying to prove that race is real. That it's not just something that we see with our eyes, that in fact there is something fundamentally different between a person who is white and a person who is Black.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Or Asian. And they looked at blood differences.

JAD: Nothing.

ROBERT: They looked at differences in musculature.

JAD: The size of our heads, nothing.

ROBERT: They couldn't really say this is this and that is that.

JAD: Then ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Clinton: ... of the entire human genome.]

JAD: ... in 2000 ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Clinton: It is my great pleasure ...]

JAD: ... Bill Clinton introduces two of the most important scientists in the world.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Clinton: Dr. Francis Collins and Craig Venter.]

JAD: Both of whom get up to the podium and say, "Look, we have searched all the way down to our DNA. Can't get any deeper than that. And when it comes to race ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Craig Venter: The concept of race has no genetic or scientific basis.]

JAD: ... it's just not there."

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Clinton: What that means is that modern science has confirmed what we first learned from ancient faiths: the most important fact of life on this Earth is our common humanity.]

JAD: But couple years down the road, if you fast forward, we began to look more closely and we began to notice ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Some subtle differences based on ethnic background.]

JAD: ... differences.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Craig Venter: Differences in people's health and race.]

JAD: And the differences seemed like they could be important.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: That some genetic diseases target racial or ethnic groups more than others.]

JAD: So that now just a couple of years later, even some of the scientists who were on the podium that day saying it was all over, even they had started to rethink.

FRANCIS COLLINS: Are we rolling?

WOMAN: Yes, we're rolling.

FRANCIS COLLINS: We are rolling.

ROBERT: Oh!

JAD: All right.

JAD: That's Francis Collins, head of the Human Genome Project.

JAD: Now in 2000, you were standing with Bill Clinton and Craig Venter. Do you remember this day?

FRANCIS COLLINS: I do remember June 26, 2000, yes. It would be hard to forget that one.

JAD: What was the weather like, out of curiosity?

FRANCIS COLLINS: It was really hot that morning.

JAD: But really, we didn't want to talk to Francis about that day. We actually wanted to ask him about something he said a couple years afterwards, something he wrote in a medical journal.

ROBERT: Jad, could you read the not—the Francis saying not ...

JAD: Oh. Well ...

ROBERT: Well, I'll just read it to you. This is you talking.

JAD: Okay. Here it is. "Increasing scientific evidence, however, indicates that genetic variation can be used to make a reasonably accurate prediction of geographic origins. It is not strictly true that race or ethnicity has no biological connection."

ROBERT: So that's what we're kind of wondering. "It's not strictly true that it has no biological connection." [laughs] That's a careful tiptoe.

FRANCIS COLLINS: I won't defend that as being the world's best sentence construction.

ROBERT: [laughs] But there's something that you want to say that you didn't quite pass through your lips, it sounds like. But ...

FRANCIS COLLINS: [laughs] Well, let me try again here. I think there are two points you can make about race and genetics. One is we're really all very much alike, incredibly alike. But you can also say even that small amount of difference turns out to be revealing.

JAD: So that's our show today. What exactly can science reveal about race? Does it exist? Does it not exist?

ROBERT: What really can you say about it?

JAD: Yes. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. Okay, ready?

ROBERT: Mm-hmm. Three, two, one. So let's go back and consider Francis Collins's statement.

JAD: "It is not strictly ..."

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Okay, stop. Stop. So it's not strictly speaking true that race has no biological connection.

JAD: Who are you?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: I'm Nell Greenfieldboyce. I'm a science reporter with National Public Radio. But for the moment, I'm your—I'm your grammar instructor.

JAD: [laughs] Okay.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: So take this double negative and make it into a sentence that is without the double negative.

JAD: It is sort of true.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: It's sort of true that race has something to do with biology, right?

JAD: Right, right, right.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: But while he is tiptoeing around with his fancy double negatives, some people out in the real world ...

KIP JUDICE: It sounds like a cell phone, and I'm getting rid of that right now.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: ... are taking that concept ...

KIP JUDICE: Get closer to the mic.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: ... and they're just running with it.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Hello, can you hear me?

KIP JUDICE: Hello, hello.

JAD: Who's—who's running with it exactly and how?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Well, I talked with one detective in Louisiana.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Let me just make sure I have your name pronounced correctly.

KIP JUDICE: Sure. My name is Kip Judice. I am the patrol commander of the Lafayette Parish Sheriff's Office with the rank of captain.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Who says that he actually used DNA to say something about race.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: When was this all going down?

KIP JUDICE: Let's see 2002, 2003.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: And that that helped him catch a serial killer.

KIP JUDICE: We had a victim who had been bludgeoned into death.

[NEWS CLIP: Trineisha Colomb was only 23 years old.]

KIP JUDICE: She was left in a field and found by some hunters.

[NEWS CLIP: It is believed her final moments alive were spent visiting her mother's grave. Her abandoned car discovered ...]

KIP JUDICE: Her vehicle was found abandoned ...

[NEWS CLIP: ... in the cemetery.]

KIP JUDICE: ... right near her mother's gravesite.

[NEWS CLIP: In just over a year, four women have been murdered in Louisiana. Their deaths linked by DNA evidence.]

[NEWS CLIP: DNA evidence at all of the crime scenes that point to a single killer.]

[NEWS CLIP: A serial killer.]

KIP JUDICE: The media dubbed him the Baton Rouge Serial Killer. It was in the news almost daily.

[NEWS CLIP: Self-defense classes are filling with frightened women.]

[NEWS CLIP: Where will he strike next?]

KIP JUDICE: Based on some witness information ...

[NEWS CLIP: The suspected killer is believed to be a white male.]

[NEWS CLIP: He is described as a white male.]

KIP JUDICE: White male in a white truck.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Everything at that point they had ...

[NEWS CLIP: Between 30 ...]

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: ... made it seem like it was probably a white guy.

KIP JUDICE: Yes.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: I mean, they had this eyewitness report. The fact that there seemed to be a serial killer, and most serial killers are thought to be white guys. And they started testing hundreds of white men.

[NEWS CLIP: Police have launched an extraordinary effort to take DNA samples.]

[NEWS CLIP: DNA samples from nearly a thousand men.]

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: They were doing kind of a genetic dragnet.

[NEWS CLIP: A dragnet for a serial killer in an area where crime tape is becoming part of the landscape. Bob McNamara, CBS News, Baton Rouge.]

KIP JUDICE: It wasn't looking very—very promising.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: So they went and they asked, you know, their crime lab ...

KIP JUDICE: Is there anything in a DNA profile that identifies race?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: I mean, we have the perpetrator's DNA. Can we look at that and say whether it's a white guy or a Black guy?

KIP JUDICE: The immediate answer we had was no, there's not.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: No. You can't do that.

KIP JUDICE: Not a—there's not a marker, there's not a gene that ...

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Because, you know, race is not biological, right?

KIP JUDICE: However, there was some technology out there that was looking into it.

TONY FRUDAKIS: We're the first company I think in the world to infer phenotypes for forensics cases.

JAD: Who's this?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: That's Tony Frudakis. He owns a company in Florida that sells tests, genetic tests, that he claims can be like an eyewitness and tell you something about a person, what they look like.

TONY FRUDAKIS: Characteristics like eye colors and hair colors and skin color.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: And the cops in Louisiana took him up on it.

KIP JUDICE: We submitted the suspect profile to them. And ...

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: And when the test came back ...

TONY FRUDAKIS: This particular case, the individual was primarily of African ancestry.

JAD: A Black guy?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Yes.

KIP JUDICE: Over 90 percent likely that it was a Black male.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: I do think it's important to note that there were other lines of evidence that had been developing that made them think a Black guy was likely. But the DNA result? I mean, that was science.

KIP JUDICE: Within three or four days after that, state police called and said, "We have a match."

TONY FRUDAKIS: The rest is history. He's since been convicted of two of the murders.

JAD: So wait, they caught the guy and he was, in fact, Black?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Yes.

JAD: So does that mean that Tony Fru—what is it?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Frudakis.

JAD: Tony Frudakis has somehow found the gene for race? That there is a race gene?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: It's much more complicated in that, and it all boils down to this idea of ancestry.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, advertisement: Ancestry by DNA.com.]

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Now you can go online to his company DNA Print, and they will send you a kit.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, advertisement: With just a simple mouth swab you do at home, you can discover your unique genetic ancestry.]

JAD: Okay. My kit.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: And it's like a little science kit.

JAD: Yeah?

ROBERT: [whispering] We're listening to Jad Abumrad taking a DNA test while being interrupted by his wife.

JAD: I'm taking a DNA test.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: And it's got these, like, swabs.

JAD: Open one of these sterile swabs.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: And you, like, rub your cheek with it.

JAD: Ah, ah, ah, ah.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: You literally just send this through the mail to the DNA Print corporate headquarters in Sarasota, Florida. And I went there.

RECEPTIONIST: Hi.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Hi.

RECEPTIONIST: How are you?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Good. I'm Nell Greenfieldboyce.

RECEPTIONIST: Oh, yeah.

JAD: Okay, so after the cheek cells arrive in Florida ...

TONY FRUDAKIS: And this is where items of evidence come.

JAD: ... and I guess they run it through a bunch of machines. What exactly in the end are they looking at that gives them, like, some sense of my race?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Well, in your DNA there's lots of information. There's billions of different little DNA letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters, letters.

ROBERT: Can we play with this just for a second? If I were to have you recite all the letters in your DNA at one letter per second, you know how long it would take you to spell yourself?

JAD: An hour.

ROBERT: No, no. It would take you ...

JAD: Six months.

ROBERT: A century.

JAD: What?

ROBERT: It would take you a century.

JAD: Really?

ROBERT: To make it even more interesting, instead of just you, let's have you compared to me.

JAD: You mean, like, if we both read it at one per second?

ROBERT: Yeah. We would be absolutely identical for about 17 minutes before there'd be any difference between us.

JAD: Wow!

ROBERT: And every difference that there is ...

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Whether it's like a little chemical T or a little chemical G or whatever ...

ROBERT: Has a story behind it.

JAD: How do you mean?

ROBERT: Well, we all started in the same place together.

FRANCIS COLLINS: Well, the evidence is very good that the human race, as we currently know it, had its origins in Africa.

ROBERT: According to Francis Collins, head of the Human Genome Project.

FRANCIS COLLINS: In the neighborhood of a hundred thousand years ago with as few as 10,000 people.

ROBERT: But soon after that, humans began to fan out across the globe. Some of us went east into Arabia, some of us went up north across the Sahara into the Mediterranean area. All the while, all these people are having babies. And in the process, the DNA is getting copied over and over and over, parent to kid, parent to kid. But sometimes the copying isn't exactly perfect. So every so often you'll find the copying error.

WOMAN: C.

CHILD: C.

WOMAN: A.

CHILD: A.

WOMAN: T.

CHILD: T.

WOMAN: A.

CHILD: C.

WOMAN: No!

ROBERT: Yes, that one right there. Let's imagine that error ...

WOMAN: A.

CHILD: C.

WOMAN: No!

ROBERT: ... occurred in Asia about 25,000 years ago. Imagine a Chinese woman had a baby, and the baby was one letter different from the mommy. An accident. The A and the mom became a ...

CHILD: C.

ROBERT: ... in the baby. And then that C was handed down. And you get another C. And you get another C. And a thousand years down the road, I look into your DNA and I see that same mistake in the same spot. You know what I know?

JAD: What?

ROBERT: I now have a hunch that if I shook your family tree really hard, some Chinese ancestors would pop out.

JAD: Hmm.

ROBERT: It's sort of like a souvenir that your ancestors handed you down in your blood that you carry with you in every cell in your body.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: So they've identified about 180 little variations in the DNA.

ROBERT: Little souvenirs.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: That people who share ancestry share, I guess, is the way to put it.

TONY FRUDAKIS: Whose sample did you send him? Was It yours?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Oh, I'm not gonna tell you.

TONY FRUDAKIS: That's all right.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: You tell me.

TONY FRUDAKIS: Yeah, we'll show you. We got it on a CD.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: So we leave the lab, and we go down this hallway to his office.

TONY FRUDAKIS: We've determined that it is of alien origin. No, I'm just kidding.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: [laughs] That would explain a lot, actually.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: He pulls these things up on his computer screen.

TONY FRUDAKIS: I'll show you what your results were.

JAD: So what does it say? I'm dying here.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Well, I guess before I tell you ...

TONY FRUDAKIS: Okay. That sample was determined to be ...

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: ... I want to know what you think. What do you think it's gonna be?

JAD: Well, my folks are Arab. Light skin both of them. My dad's got some darker skin people on his side of the family. So if I had to guess, probably some European in there. And then my dad's side I was thinking, well, they're probably like Greek or Turkish way back when. I wasn't really sure, and I consciously didn't sort of look into it.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Okay, well let me just tell you that this test you took is not gonna tell you countries.

JAD: [laughs] Right, right.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Okay.

JAD: I'm oddly kind of nervous, weirdly.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Really?

JAD: Yeah, just a little bit.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: So your sub-Saharan African ancestry, what percentage are you thinking?

JAD: I'm gonna guess 12?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Zero percent.

JAD: Zero?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Zero percent.

JAD: Huh. All right.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Native American ancestry, one percent.

JAD: One?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: East Asian, five percent.

JAD: Wow!

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: European, 94 percent.

JAD: Really?

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: 94 percent.

JAD: 94 percent European?

ROBERT: No, 94 percent pansy.

TONY FRUDAKIS: Note that the words that we're using here are pretty arbitrary.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: You should understand that his definition of quote-unquote "European" includes ...

TONY FRUDAKIS: The Fertile Crescent or the Middle East.

ROBERT: What? So wait a second. If I'm a policeman—remember, we started this conversation and a cop was looking to describe a perpetrator.

JAD: Right.

ROBERT: So if I find out that Jad Abumrad is European, then I'm looking for someone who could be—it's a huge range.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: We're looking at the computer screen now.

JAD: For example ...

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: You've pulled up a bunch of digital photos.

JAD: ... when Tony Frudakis pulled up pictures of people with my exact ancestral mix ...

ROBERT: Yeah?

JAD: ... you know, from this database ...

TONY FRUDAKIS: Okay, database. Here's some males, here's a female.

JAD: ... he brought up people with blonde hair, blue eyes.

TONY FRUDAKIS: These are all people that had this sort of mix.

JAD: Even people from Poland who had, like, really red cheeks.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: So these folks just look like pretty much like white folks to me.

TONY FRUDAKIS: Run of the mill.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Because I gotta tell—let me show you the picture of the guy who actually gave the sample.

ROBERT: Now Mr. Frudakis does not know that Jad is a dark, curly-haired, swarthy man.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: So this is the guy. And he doesn't really know anything about his ancestry, but his mother and father I believe are from Lebanon.

TONY FRUDAKIS: Although in this sample of maybe 20 people, it's just we don't have any samples of Lebanese in this particular ...

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: But I guess I'm saying is for a cop, someone who describes themselves as Lebanese versus Polish, I mean, that would be a really big difference.

TONY FRUDAKIS: Oh, yeah. And to make that sort of distinction you need different markers.

ROBERT: So then what does DNA actually tell you then?

JAD: Well, not a lot that's direct. What he's doing basically is playing a guessing game based on ancestral percentages. Like, for instance, I'm 94 percent European, zero percent sub-Saharan. He can plug that into his database, pull up the pictures, and he will notice that nobody with those percentages is Black. So he can tell—he'll tell police, this guy? Probably not Black.

ROBERT: Just like at the beginning we said that the perpetrator there was pretty much not white.

JAD: Yeah. Now there is one thing that he can read directly in our DNA.

ROBERT: What?

JAD: Eye color.

ROBERT: Hmm.

JAD: So at the end of the day he can say I am not Black and I have brown eyes.

ROBERT: [laughs] That's it? That's as far as he can go?

JAD: That's all he can tell you as a scientist. He does take it further.

ROBERT: What did he do?

JAD: Well, if he's got a DNA sample of a perp, he can go to his computer database and he can say ...

TONY FRUDAKIS: Okay, database.

JAD: "Show me everybody who's got these exact same percentages. Show me their pictures. Now tell me what all of these faces have in common visually. Like, what's their average ..."

TONY FRUDAKIS: Nose width.

JAD: What's their average ...

TONY FRUDAKIS: Shape of the ears.

JAD: How big are their skulls?

TONY FRUDAKIS: Skull shape.

JAD: You see where this is going?

ROBERT: And then what he tells the police to look for ...

JAD: Look for people who have, you know, this type of head, kind of ear.

ROBERT: But this isn't genetics now. This is just photo averaging.

JAD: Photo averaging, yeah.

ROBERT: So this isn't science. This is something else.

JAD: Right, but when you hear things like measuring skulls, measuring ears, it's hard not to think back to pretty nasty periods of our history. Like the eugenicists, they tried to composite pictures into one face. They measured skulls, and they ended up inspiring the Nazis.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: Have people called you a racist?

TONY FRUDAKIS: Not once. Not once have I been called a racist. Not once.

NELL GREENFIELDBOYCE: And that kind of surprises me. I'm just sort of wondering how do you think you've escaped that?

TONY FRUDAKIS: Hmm, are people critical of this? Yeah, I think a lot of scientists their first knee-jerk reaction is—is that the poor masses out there aren't intelligent enough to handle this sort of information. They'll start climbing over one another and killing themselves so that we either, you know, the smart ones need to sort of obfuscate. And I don't think that works very well. People may be a lot smarter than we might give them credit for being.

ROBERT: I think he's onto something there.

JAD: What do you mean?

ROBERT: Well, there is a tendency that people have when this subject comes up to say, "Shh-shh. We don't talk about that." I think people can talk about the real world and real differences respectfully, and even with a certain amount of delicious interest.

JAD: Sure. Yeah.

ROBERT: Well, you say sure, but there are lots of shushers everywhere.

JAD: You're not gonna get me to stand on the side of shushing. It's just—I mean, science complicates things. Even now this whole, you know, definition that science has of race being like ancestry or whatever, it just—it just doesn't jive with how people live race.

ROBERT: You mean how people talk about it really?

JAD: Yeah. Well, look here. Take a look at this photo.

ROBERT: This one here?

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: Yeah?

JAD: You see the guy there?

ROBERT: Yes.

JAD: What race do you think he is?

ROBERT: He's Black.

JAD: Definitely Black?

ROBERT: Definitely. Oh, yeah.

JAD: How Black is he?

ROBERT: How Black is he? What kind of a question is that?

JAD: Yeah, just sort of visual.

ROBERT: Black-Black.

JAD: How about Obama Black?

ROBERT: No, he's not. He's blacker than that.

JAD: So he's unequivocally Black, right?

ROBERT: Well, I don't know.

WAYNE JOSEPH: My parents taught us, because they came from a segregated South, you were either Black or you were white. There was no in between.

JAD: So the guy you're looking at, the guy we just heard?

ROBERT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: That's Wayne Joseph. He's an education director in LA, and he also on the side writes essays about race mostly, for national magazines. And one day a couple years back, he was watching TV.

WAYNE JOSEPH: And I happened to see a TV program highlighting the fact that a couple of DNA labs were actually doing racial testing on DNA.

JAD: A light bulb went on.

WAYNE JOSEPH: I said, "Well, this will be perfect for this essay."

JAD: He thought he'd test himself, see what percentage of him was Black versus other stuff, and then write about it.

JAD: But what number did you think you would be?

WAYNE JOSEPH: The number I was thinking was 70 or 75 percent or more.

JAD: 75 percent African and 25 percent who knows what?

WAYNE JOSEPH: So I sent away for the kit.

JAD: Swabbed both cheeks, put it in a vial, sent it back.

WAYNE JOSEPH: And then a few weeks later I get back the results. First thing I did was I checked the kit number to make sure that they hadn't made a mistake and sent me someone else's results. But the kit number matched. I couldn't believe it. 57 percent Indo-European, 39 percent Native American, four percent Asian and zero percent African.

JAD: Zero percent. As in zero?

WAYNE JOSEPH: Mm-hmm.

JAD: Nothing?

WAYNE JOSEPH: I mean, I've—I've lived 50 years as a Black man, and I have no African genetically.

JAD: How did you make sense of that? Did it sink in all at once?

WAYNE JOSEPH: No. What happened was after a couple of days—I hadn't told my wife anything yet—I went to see my mother. And I said, "Look, there's only one really logical explanation I can live with. It's okay. I love you. Just tell me the truth. I'm adopted." [laughs] She kind of giggled and she said, "Look, I can remember every pain I had having you. I can still remember it." I said, "Well, but then this doesn't make any sense." She said, "Yeah, it's a little surprising, but I'm too old, too tired to be anything else, so that's just the way it is. For my brother, when I told him the results, he said, "Wayne, that's your DNA, that's not my DNA. I'm a Black man." And that's the end of it for him.

JAD: Hmm. What about your wife?

WAYNE JOSEPH: Well, my second wife happens to be Jewish. Her response was, "What do you mean? You're a Black man. I defied my mother to marry you. You've got to be Black."

JAD: Whoa. So she needed you to be Black?

WAYNE JOSEPH: Absolutely. Because she had told her mother at the time, look, I'm marrying Wayne. You're going to have to decide whether you're going to accept him or lose your daughter. It really threw me for a loop. You start thinking about your life. There are certain decisions that are made in life based on who you think you are. Would I have married a Black woman the first time? Would I have decided to go to a Black high school?

JAD: Do you have answers to those questions? Would you have married a Black woman? Would you have gone to a Black high school?

WAYNE JOSEPH: Maybe not. How different would my life have been if I'd have known this 45 years ago?

JAD: Wayne Joseph is the director of alternative education for the Chino Valley School District in California.

[LISTENER: Radiolab is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the National Science Foundation.]

JAD: This is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: And I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Today's program is about race.

ROBERT: Okay, so where are we? What have we learned ? We've learned that scientists, when they talk about race ...

JAD: They don't really mean race.

ROBERT: No, they mean that you have a set of ancestors who lived in a particular place on this planet for a while. While they were there they acquired certain features: skin color, hair texture, whatever. And scientists won't go much further than just that.

JAD: But here's the thing, if you—forget the lab scientist for a second, if you're a doctor and your job is to save lives, you can't help but notice that there are real differences between groups in terms of how healthy people are. And if you want to treat that, you end up talking about race, and it never goes well. Let me tell you a story now, comes from our producer Soren Wheeler, and it's about a drug called BiDil. So you popped a few BiDil this morning?

SOREN WHEELER: [laughs] I did. I just wanted to test it out. It's supposed to—it loosens up the arteries, that's supposedly so it's easier for the heart to pump.

JAD: Hmm.

SOREN: As a white man that's about to talk about race on the radio, I figured it's time to loosen up.

JAD: Okay. Introduce me to our main dude here.

JAY COHN: I'm Doctor Jay Cohn, a professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

SOREN: This is him.

PRODUCER: And what did you have for breakfast this morning?

JAY COHN: I don't eat breakfast.

JAD: Tell me what he looks like.

SOREN: Well, he's stocky, he's got a white beard. He's kind of got that wearied grave doctor look, probably because he spent his entire career worrying about how to help people with heart failure.

JAY COHN: That's right.

SOREN: Which for a really long time was kind of a lost cause.

JAY COHN: Oh, yeah. It was a hopeless disease. And once it developed, the implication was that the patient would die.

SOREN: You're done.

JAY COHN: There was nothing much we could do but keep the patient comfortable.

SOREN: But then ...

JAY COHN: Back in the early '70s ...

SOREN: ... Jay had kind of a breakthrough.

JAY COHN: The "Ah-ha" moment was the first patient. Bedridden patient, can't breathe easily, bubbling up with fluid in the lungs.

SOREN: Jay gave this patient a combination of two drugs.

JAY COHN: And the moment we did that, this patient suddenly said, "My God, I can breathe easily for the first time in months."

SOREN: That fast?

JAY COHN: Oh, it's immediate.

SOREN: He confirms the effect in a longer-term trial over five years. He gets a patent. He finds a company, they put it in a pill and they take it to the FDA.

JAY COHN: And that's when the FDA said no.

JAD: No?

SOREN: No.

JAY COHN: That's what they said.

JAD: Why no? You just said it worked really well.

SOREN: Well, the doctors on the review board, they said they thought the drug was pretty good.

JAY COHN: Yeah.

SOREN: They even started using it with some of their patients. But they denied approval ...

JAY COHN: Because it was not a big study.

SOREN: The study was just too small.

JAY COHN: In the entire trial there were only 86 people.

SOREN: That got the drug.

JAD: Hmm.

JAY COHN: We were disappointed, frustrated. We were using it, I was using it in my patients.

JAD: Drag.

SOREN: Yeah. So he goes back to what he was doing before all this started, which was trying to figure out what the hell's going on with heart failure.

JAD: What the hell was going on with heart failure at that point?

SOREN: Well, at the time scientists were just starting to look at racial differences.

JAD: Hmm.

SOREN: When it comes to things like high blood pressure and heart problems, that Black Americans were suffering a lot more than white Americans.

JAD: I see. So he must've been hearing all this stuff.

SOREN: This debate was going on out there. And Jay was listening. So Jay started thinking, you know, he had all that old data, and they had actually broken it up ...

JAY COHN: By race. Everyone checked a box.

SOREN: Black, White, American Indian, all that. They'd never bothered to look at that stuff.

JAY COHN: Never teased it out. And I said, "We should go back into our database."

SOREN: Because just maybe, maybe Black people respond differently to BiDil.

JAY COHN: Well, we thought it would be worthwhile to go back and look. We didn't know what we were gonna find. We just went back and checked off those people who had said they were Black.

SOREN: Jay's assistant gathered up the data, and when they looked at the numbers ...

JAY COHN: Oh my God!

SOREN: He saw a bump.

JAD: What do you mean?

SOREN: Well, still just a small trial, but in that trial the Black patients did better.

JAY COHN: Significantly better.

JAD: Really?

SOREN: So he published, and a couple of weeks later he gets a call from a drug company and they say, "We'd like to do something with BiDil."

JAY COHN: They would be willing to do a trial to demonstrate the efficacy of BiDil.

SOREN: But here's the thing: they wanted to do the trial just with Black people.

JAY COHN: That seemed to be the path of least resistance.

JAD: Why would they want to limit it just to Black people?

SOREN: Well, they could do a smaller study so it would be cheaper. And when it came time to sell the drug, ready-made market.

JAD: All right, so they do this big study only in Black people.

SOREN: Only in Black people.

JAD: And what do they find?

SOREN: An amazing result.

JAY COHN: We get a 43 percent reduction in mortality.

JAD: Wait, what?

SOREN: In other words, if you were a Black person in this trial and you took BiDil, your chance of dying from heart failure was cut in half.

JAD: Whoa!

SOREN: Roughly.

JAD: That's huge.

SOREN: It's huge. Yeah.

TROY DUSTER: So they go back, and in 2005 ...

SOREN: That's Troy Duster, a sociologist at NYU.

TROY DUSTER: The FDA approves this as the first racialized drug. Think about that: the first racialized drug. The first drug ever approved for a racialized subpopulation.

SOREN: After hundreds of years of looking for differences between Black people and white people, after the mapping of the human genome, here's the FDA saying we're different.

TROY DUSTER: Well, some of us said this is a huge mistake.

JAY COHN: We knew this was a terribly sensitive issue.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: As we move into the 21st century well aware of the terrible history of racial and ethnic categories, what should we do?]

JAY COHN: We had a symposium ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: I'd like to welcome you all program ...]

JAY COHN: ... here at the University of Minnesota.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: We actually have a sold out crowd today.]

JAY COHN: And it was mainly aimed at attacking me.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: I just don't think race is a scientific category.]

JAY COHN: And there was a very well-known law professor so hostile to the idea that she said, "I would rather die from heart failure than take BiDil."

SOREN: Well, that's not quite what she said.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: I'd be terrified about a doctor making a diagnosis like that based on their view of me as belonging to a particular racial category.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Jay Cohn: Well, but it goes on all the time.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: That doesn't make it right. That's what I'm saying. You know, that doesn't—that's right. It does.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Jay Cohn: If you ...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: And these categories have—you know, it's—look ...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Jay Cohn: You would object then to a doctor seeing an African American with anemia.]

JAY COHN: I said if you went into the doctor's office and were anemic, the doctor would appropriately check you for sickle cell.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Jay Cohn: Just a natural, everyday phenomenon.]

JAY COHN: And she insisted, well that's wrong.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: Either there's ...]

JAY COHN: Because sickle cell disease is not confined to Blacks.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: ... people have been misdiagnosed.]

JAY COHN: Well, she is right, of course. But the statistical likelihood of a white person with sickle cell disease is so low.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: ... and damaging.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Jay Cohn: But they're prevalence issues. There is a higher —we can look at a patient and help identify some processes of diagnosis and treatment that might improve our precision. To disregard that, we need a better way to do it.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: Well, but that's just it. I think ...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Jay Cohn: In the year 2005 that's what we have.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, law professor: But you know what? I think that if we—if—seems to me that these racial categories are impeding good medical care and good biomedical research, they're not assisting it.]

ROBERT: Well, I don't get that at all. Why would declaring a difference impede? It seems exactly the opposite. If you know that a group of people are likely to get sick in a certain way, then you should target them and help them and give them the ...

JAD: Right. But the question is do you know what you think you know, I think is what she's saying. And by looking at one target group are you somehow shutting yourself off from the real target group that you should be looking at?

ROBERT: I don't know what you're talking about.

JAD: Okay. Let me give you an ...

ROBERT: We all know that Black people ...

JAD: Let me give you an example, okay? When you go to the doctor ...

ROBERT: Yes.

JAD: ... and they put that thing around your bicep and they go "pfft-pfft-pfft-pfft."

ROBERT: Yes, the squeezing.

JAD: Yeah, blood pressure. It's well known that Black Americans have much higher rates of high blood pressure, hypertension ...

ROBERT: Yes it is.

JAD: ... than White Americans.

ROBERT: Which is my point, that so that if people know that ...

JAD: Hold up.

ROBERT: If you know that ...

JAD: Hold up. It can seem like it's caused by race or it's purely a racial phenomenon. But then I mentioned this to Troy Duster. I said, "How do you explain this? Black Americans suffer, like, twice the amount of hypertension than white Americans. Make the argument for me that this is somehow not an innate difference."

TROY DUSTER: Okay. The best argument here is Richard Cooper's work.

RICHARD COOPER: I'm Richard Cooper. I'm the chair of the Department of Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology here at Loyola.

JAD: Richard Cooper is a doctor and a researcher, and here's what he did. He went to poor neighborhoods in Chicago and methodically ...

RICHARD COOPER: House to house, taking blood samples.

JAD: ... measured people's blood pressure. And then he took that data and compared it to other countries.

RICHARD COOPER: Canada, Spain, Italy, United Kingdom ...

TROY DUSTER: That's huge. Eight nation sampling, 85,000 people.

JAD: 85,000 people?

TROY DUSTER: 85,000. He then arranged nations in terms of hypertension.

JAD: Because he wanted to know, like, who's got the highest rates, who's got the lowest, and does this really have anything to do with race?

TROY DUSTER: Right.

ROBERT: And?

RICHARD COOPER: At the very end, the nation with the highest rate of hypertension known ...

JAD: Drumroll please.

RICHARD COOPER: ... was Germany.

JAD: Germany?

RICHARD COOPER: Germany.

JAD: Actually, Richard Cooper says that Finland, Poland and Russia are even worse.

RICHARD COOPER: Right.

JAD: Okay. How many Black people are in Russia?

ROBERT: Seven.

JAD: [laughs] Probably seven.

RICHARD COOPER: And the nation with the lowest rate of hypertension known is Nigeria.

JAD: No kidding?

RICHARD COOPER: Yeah. And it's like this. It's not like this, it's like this.

JAD: You're putting your hands way apart from each other.

RICHARD COOPER: Yeah.

ROBERT: Your point being here what, exactly?

JAD: Is it not obvious? I mean, if you're a doctor ...

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: ... and you're just focused on the United States' data, you would assume that it has something to do with race, these high blood pressure disparities. So you'd therefore A) miss all the Russians and Finns that came into your office; B) you would overtreat the American Blacks; and C) God forbid a Nigerian should walk in because you're gonna give him all these drugs he doesn't even need.

ROBERT: Well, then what does cause the differences?

JAD: Like, if it's not race what is it?

ROBERT: Yeah. If not race, what?

JAD: Diet.

ROBERT: Diet?

JAD: Yeah, diet.

ROBERT: Really?

JAD: According to Richard Cooper. I know it's not that exciting but that's what he says.

ROBERT: Well then what about BiDil then? You think that's wrong too?

JAD: No. I mean, but if you are the first drug ever to be approved for Black people ...

ROBERT: Uh-huh.

JAD: ... wouldn't you want to know that your drug works better for Black people as compared to other groups?

ROBERT: Yes.

JAD: And you'd want to be sure, right?

ROBERT: Yes.

JAD: Well, they only ever tested it in Black people. They never actually compared Blacks to whites.

JAY COHN: Yeah, well that's true. We don't know, and we haven't gone back and studied a large white population. And I personally believe that BiDil will work in white people as well, maybe not to the same frequency. But I use it in my white patients.

SOREN: Are you at all then upset that it's ...

JAD: That's Soren Wheeler again.

SOREN: ... it's FDA approved only for Blacks?

JAY COHN: Well it's not getting to Blacks. I mean, that's the real tragedy.

JAD: What's he talking about?

SOREN: Well, in the end, BiDil kind of tanked.

JAD: Why?

SOREN: You know, the way they priced and marketed the drug, all that kind of stuff. But according to Jay, it was also because of opposition to the idea ...

JAY COHN: To the concept ...

SOREN: ... of BiDil.

JAY COHN: ... that this is the drug for Blacks. It's a crime that this life-saving drug is not being as widely used as it should be. I'm very discouraged about that.

ROBERT: So the takeaway here, I guess, is if a doctor or a scientist or a pharmaceutical company announces that there is a racial difference in the human family, check the footnotes.

JAD: [laughs] Exactly.

ROBERT: On the other hand, I think an awful lot of us in our regular life get all excited about racial differences when we watch sports. I mean, everyone notices, for example, in track and field.

JAD: Like, why do all the Jamaicans win?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: Always Jamaicans.

ROBERT: So we found a Jamaican—our own Jamaican—Malcolm Gladwell, a writer.

JAD: He's sort of Jamaican.

ROBERT: He's Canadian Jamaican English. Also the author of The Tipping Point and, I don't know, all those bestselling books. We talked to him about his early days as a runner.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: My running weight when I was 13 and 14 was about 105, 100.

ROBERT: So you, like, just kind of danced on the ground.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: I'm 30 pounds heavier than I was in my running prime.

ROBERT: Are you good? You can be ...

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Yes. At that age.

ROBERT: Yeah.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Am I good in the global sense? No. Was I good at 13? I was really good. I was—I was All-Canadian, yeah.

ROBERT: Oh, you were number one in your country in what event?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: 1,300 meters. Age-class track and field in Ontario in the 1970s was so overwhelmingly West Indian, it was—in retrospect it's hilarious to think back on it. I mean, you would go to these track meets, and there's like reggae music playing the entire time, and the stands are full of Jamaicans. So you were dealing with this fact, you know, you're 13, you're not very sophisticated. You're dealing with this fact that there just aren't any white people, it's all Jamaicans. In lanes one through eight are all Jamaicans. Right off the boat Jamaicans. And so you begin—and when you see—it was really funny. I remember there was a guy named Arnold Stots, and Arnold Stots dominated the quarter mile for years in age-class running.

ROBERT: Arnold Stots was a white guy?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: He was a white guy. And we all looked at Arnold and we said, "It's not gonna last. Can't last." Sure enough, it didn't.

ROBERT: You thought Arnold won't make it because he does have the right stuff. The right stuff being whatever it is that Jamaicans got.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: He's not Jamaican. The question was how long can Arnold keep beating the Jamaicans? And the answer is it can't be for that much longer. And he was a tremendous sprinter. But we had this kind of unspoken prejudice that said if you weren't Jamaican it was hopeless.

ROBERT: And did you ever have an opportunity at the age of 14 to ascribe this to anything?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: I mean, I began to kind of process it in a very, very crude, unsophisticated way. And then I would look at the world, and I would see in the world Black people won all the sprints. So I figured well, maybe just Black people are faster than white people.

ROBERT: So in a very primitive, young guy kind of way, Malcolm was—I don't know exactly what the polite word for this is—but he was a racist. Or more of a chauvinist maybe, or just somebody who sees West Indians winning everything, so he figures there's gotta be a genetic advantage here because he could feel it in himself.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Listen, I had that gift. I was really, really good when I was 15 and 14 and 13. I was the best in Canada. I used to beat Dave Reid. Dave Reid went on to be ...

ROBERT: You beat Dave Reid?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Dave Reid went on to be on the Canadian Olympic team.

ROBERT: Oh, really?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Yeah.

ROBERT: Okay. So that was the thing.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: That was the caliber of runner I was then.

ROBERT: How old were you and Dave Reid at the time when you were beating him?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: 14.

ROBERT: [laughs] Okay. Let's make that clear.

ROBERT: But now that he's older ...

MALCOLM GLADWELL: ... and slower.

ROBERT: ... and slower, he's revised his thinking in this area.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: I no longer am all that enamored of a kind of genetic case for Black athletic superiority. I think it maybe explained some tiny amount but it's not the real issue. Nature takes care of the fundamental things in the beginning, and then as we—as activities grow more involved and more complex, individual choice starts to matter more and more and more and more.

ROBERT: And when he says individual choice, he's thinking of the moment when you're an athlete and it's the last turn or maybe the last lap of a race.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: When you've run 1,200 meters in the 1,500-meter race, or you've run six miles of a seven mile cross-country race you're beginning to suffer. Pain is about to start. You're in a position where you possibly can win if you exert yourself.

ROBERT: And that's the moment, says Malcolm, when every athlete has to ask ...

MALCOLM GLADWELL: How much do I care? There's always a struggle. Do I really care? Does it matter to me?

ROBERT: Do you think that Mickey Mantle or—or ...

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Oh, I think everyone has it.

ROBERT: You think?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: All athletes have that question. Some people say, "I do care," and some people say, "I don't."

ROBERT: And how you answer that question yes or no has very little to do with genes, says Malcolm.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: That's not the critical difference between me and Tiger Woods, you know? It's that Tiger gets up at five in the morning and hits 10,000 golf balls before breakfast. That's the difference. Why does he want to do that, and why is it inconceivable for me to do? There's your interesting story.

ROBERT: In Malcolm's case, he says he did love running.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: You know, when you're that age, you really can't run forever. I'll never forget the feeling.

ROBERT: But he also loved reading books, and he loved going to school, and he loved thinking, and he loved ...

JAD: Ping pong!

ROBERT: He might've liked ping pong. I don't know.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: My father comes from that glorious tradition of English amateurism which says you should do many things and none of them well. [laughs]

ROBERT: All of which, in that critical moment, made answering, "Yes, I will put up with the pain and win this race," a little bit more difficult.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: I struggled with it and I—there was a moment when I had that conversation and I said I didn't care.

ROBERT: And the moment happened when he was preparing for the Canadian National Championship ...

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Canadian championship.

ROBERT: ... with two of his friends who were also Black.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: I go for a run with this guy Dave Reid, who's this great runner of our generation.

ROBERT: The Dave Reid.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Yeah, and another guy named Chris Brewster, another great runner of my generation. At the time we would've thought of ourselves as equals.

ROBERT: But those guys didn't have as many options as Malcolm.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: And there's a famous hill called Telegraph Hill, or no, Signal Hill. Steep as the steepest—it's like running up the steepest flight of steps you've ever—I mean, it goes up for miles.

ROBERT: So it goes up kind of like San Francisco steep?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Yeah, goes up forever. And the first day, I think we ran up it and I just thought, "This is ridiculous."

ROBERT: Because you're huffing and puffing or because ...

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Just like, why would we do this? Like, it just seemed crazy. And then the next day we went there we ran, like, seven miles to Signal Hill, and then Dave Reid and Chris Brewster decide they wanted to run up the hill backwards.

ROBERT: Really?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Which is, you know, you've just run seven miles at probably 5:45 pace. It's six in the morning, and they want to run up this huge hill backwards. And I—I said no and I went home. I didn't want to run anymore. I wanted to be on the debating team, and I wanted to read books and I wanted to hang out with my friend Terry. I quit.

ROBERT: So what is left to say about these genetically-based racial differences in your mind?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Very little.

ROBERT: So all the things that we've been talking about in this show: maybe there is a tendency to get sick in a certain way, maybe some medicines work a little better for one group than another, let's say it's all true.

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Yeah.

ROBERT: You say it's true, but it's not true enough to mean anything but a very short story?

MALCOLM GLADWELL: Yeah. I mean, I'll grant you all those things, and then I'll roll my eyes and say I don't really care.

JAD: Malcolm Gladwell's latest book is called Outliers, and Radiolab will return in a moment.

[LISTENER: This is Chad Kenickie calling you from my living room in Cincinnati, Ohio. Radiolab is supported in part by the National Science Foundation and by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org. Thanks.]

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: And I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. Our topic today is race, what science can or cannot tell us about race.

ROBERT: Now that we're towards the back end of the program ...

JAD: The front end or back end?

ROBERT: We're at the front end of the back end. We can confess that what we asked before: what could a scientist tell us that's hard and true about the biology of race ...

JAD: Nothing!

ROBERT: No, it's better than nothing.

JAD: All right, something.

ROBERT: But once you drop the science part of race and think of it as just a way of sorting people into us's and thems, then it gets interesting.

JAD: Or at the very least, more complicated.

CHILD: I didn't know!

JAD: Here's an example. We're uptown Manhattan, it's 1:00 p.m. Third period's about to start. We're at a charter school called Facing History which has about 150 kids, mostly Hispanic. And we'd come because we'd heard that every year in the ninth grade they do this particular guessing exercise.

DAVID SHERRIN: Okay. All these microphones and other people that you guys see today, they are not in the room. You can ignore them like sometimes you want to ignore me. All right?

JAD: This is first-year teacher David Sherrin. He tells his class of about 12 freshmen to pull up their seats into a semi-circle.

DAVID SHERRIN: Same class style as always. Let's go.

JAD: And to get on their race goggles.

DAVID SHERRIN: All right. So we have an activity here called "Sorting people."

JAD: After handing out some worksheets, David kills the lights, flips on his overhead projector and immediately eight faces appear projected onto the wall.

DAVID SHERRIN: What I want us to do is go kind of one by one and try to decide, try to come to a consensus okay, what race are these people based on looking at them, and then we'll test it out.

JAD: He explains they've got four choices: Black, white, Asian and Native American.

DAVID SHERRIN: So why don't we start out with the first one, the woman on the top left.

JAD: Pink cheeks, light-skinned, bushy hair, big Filipino nose. At least that's how it looked to me.

DAVID SHERRIN: Demaro, what do you think?

DEMARO: White.

DAVID SHERRIN: Richard?

RICHARD: Black.

DAVID SHERRIN: Tasha, what do you think?

TASHA: She just seems white, but then when you look at her hair it seems like that she's Black.

DAVID SHERRIN: David?

DAVID: I'm gonna go with white.

DAVID SHERRIN: So what do we think for the man on the bottom left?

JAD: Mustache, borderline afro.

BOY: Asian.

GIRL: Native American.

JAD: A vaguely ethnic version of Tom Selleck.

BOY: I'm picking between white and Asian.

BOY: White or Asian or Native American.

BOY: I think he's Black.

BOY: Black.

BOY: Hispanic?

DAVID SHERRIN: We're actually not gonna use "Hispanic." So let's take a vote here. How many people say Black? Three, okay. White? Or how many people say Native American?

JAD: All right, to cut to the chase, after eight of these faces, David revealed the results. Turned out, pink face girl was Black, Tom Selleck was Asian, and all in all the class got three right.

DAVID SHERRIN: Three out of eight.

JAD: Which thrilled David.

DAVID SHERRIN: What does this tell us?

JAD: One of the kids in the back of the class, a girl named Bianca, finally says, "Well, what it tells us is this activity ...

BIANCA: It's retarded. Sorry. It's stupid.

DAVID SHERRIN: Why?

BIANCA: Because it's stupid.

DAVID SHERRIN: Could you be a bit more specific?

BIANCA: [laughs] Okay. So let's say that you had a white mother and a Black father, the child will come out brown.

BOY: No, it'd come out gray.

BOY: Right.

BIANCA: How would it come out gray? No, it will come out brown, okay? I'm not white or Black, I'm Dominican. My mother is light skinned like David's color, and my father is dark-skinned and I came out a mixed color. I'm brown. So is brown a race? So I guess I'm brown then.

JAD: Interestingly, in the cafeteria after class when we asked people how they identify ...

JAD: This is gonna sound like a dumb question, but what race are you?

JAD: ... most people said something like this.

GIRL: Trinidadian

BOY: Ecuadorian.

GIRL: Dominican.

JAD: They named the country.

BOY: Mexican.

BOY: Jamaican.

BOY: I'm Colombian.

GIRL: Puerto Rican.

JAD: Almost no one said I'm one of those four official categories. If they mentioned it at all it was just to say that they're somewhere in between, or that they switch back and forth.

BOY: Half Puerto Rican, half Salvadoran.

BOY: I'm a mix of Black people and Hispanics.

BOY: I'm Mexican but I'm not 100 percent Mexican.

BOY: My spirit is Black. You get what I'm saying?

BOY: If I'm, like, in my neighborhood, people see me as Spanish. But if I go, like, to my grandmother's block people see me as, like, white.

BOY: When I go back home to Cuba everybody, "Oh, that's the Black kid." But when I come here all of a sudden I change my race, so I become Hispanic.

ROBERT: Do you do that too?

JAD: Do I race shift like these kids? No. I mean, I get confused a lot.

ROBERT: I mean, you could pass as a Jew, I think, even though you're an Arab.

JAD: Oh yeah, in New York? Forget it. But what's interesting is these kids, it wasn't like they were unaware of race. I mean, they're aware of it. It's just fluid for them, because I guess so many of them can pass for different things, it becomes then all about, like, what you wear, what you listen to, like, small things in the end.

ROBERT: But in some circumstances—we all know this—the tiniest differences can suddenly mean everything. We talked to—we're gonna switch locations here from New York to Baghdad in Iraq. We talked to an Iraqi guy named Ali Abbas ...

ROBERT: ... who works as a translator, as a journalist in Baghdad.

ALI ABBAS: Yeah, with NPR Baghdad office.

ROBERT: And when you were growing up in Baghdad, when you were kid, did you know whether you were Shia or Sunni?

ALI ABBAS: No. No, no. The first time I knew that I was a Sunni or a Shia, in fact it was sixth grade. We were sitting after a class break, and someone asked me if I'm a Sunni or a Shia. Like, another kid. I remember it was a Tikriti-kid because ...

ROBERT: That's the village where Saddam Hussein grew up.

ALI ABBAS: Where Saddam—yeah. That's the town where Saddam grew up.

ROBERT: What did you answer?

ALI ABBAS: I answered, "I don't know." [laughs]

JAD: Because you really didn't know?

ALI ABBAS: I really didn't know. So they made fun of me, and I returned home and I said to my mom, "Am I a Sunni or a Shia?" And the first answer from my mom was a slap on my face.

JAD: Really?

ALI ABBAS: Yeah.

JAD: Why?

ALI ABBAS: She said, "Never ask about these things. You're a Muslim, and that's all what you care about."

ROBERT: But that was then, this is now. Today, says Ali, in Baghdad you can't go around saying, "I don't know who I am." Now you have to choose.

ALI ABBAS: Yeah.

ROBERT: Even if you don't want to.

ALI ABBAS: May, 2007. A friend of mine, close friend of mine, he calls me and says, "Ali, did you hear about what happened to me?" And I'm like, "No, what happened?" He said, "My father, they kidnapped him." His father is an old guy, 62. Was just in his neighborhood buying candies for his grandson.

ROBERT: And then he disappeared.

ALI ABBAS: Just disappeared. No one knows.

ROBERT: And in Baghdad, when someone's kidnapped they usually don't come back. Usually, the body just shows up in the morgue. So what Ali's friend wanted is he wanted to go ...

ALI ABBAS: To Baghdad morgue to go and find his father.

ROBERT: But the problem was his friend couldn't go alone.

ALI ABBAS: Because he's Sunni. His name is Ahmar. And the morgue is completely controlled by Shia.

ROBERT: If a Sunni man was trying to get his relative's body out of the morgue, somewhere along the line, the Shia militia ...

ALI ABBAS: They will check the names, and they would ask him about something, you know, deep Shi'ite religion questions. And if he fails, then so they would just lynch him.

ROBERT: They would what?

ALI ABBAS: They would take him out of the hospital to somewhere, and they'd probably kill and dump his body somewhere.

JAD: Can I ask a really dumb question?

ALI ABBAS: Sure.

JAD: You're walking through Baghdad. You're walking to this hospital, you see a Sunni, you see a Shia, can you tell the difference with your eyes at all?

ALI ABBAS: Sometimes you can't really know.

ROBERT: But sometimes you could take advantage of this confusion to help a friend. Ali, after all, was always helping journalists get around Baghdad, and you never knew who was gonna be asking you questions. Sometimes it would be a Sunni militia, sometimes a Shia militia.

ALI ABBAS: It's very hard to know.

ROBERT: So journalists would go around the town with two IDs simultaneously. One would be a Shia ID, the other a Sunni ID.

ALI ABBAS: And they're putting it, like, somewhere in their pockets. You know, the right is the Sunni, the left is the Shia.

JAD: Wait a second. The right is the Sunni, the left is a Shia?

ALI ABBAS: Yes.

JAD: So if in that split second you think this guy's Sunni you go right?

ALI ABBAS: And if you're Shia you would go left. That's ...

ROBERT: You know, if it were me, I just—I know how I'd die. [laughs]

JAD: You would.

ALI ABBAS: But it's not—it's not really fun, though.

ROBERT: Especially when your job on this particular day is to take your Sunni friend into a hospital controlled by a Shia militia. So Ali decided that to protect his Sunni friend Ahmar, maybe the best protection would be a slight name change. When they went to the hospital they would call him Amaar, not Ahmar.

ALI ABBAS: Ahmar is a pure Sunni name. Amaar is something in the middle. Could be Sunni or could be Shia.

JAD: And is the same—is there different spellings?

ALI ABBAS: Different spelling, yeah. Different spellings.

JAD: They sound almost identical.

ALI ABBAS: Yeah. But just the Alif or the A in the middle.

ROBERT: And by adding that one letter, that one extra A, Ali hoped that would keep his friend alive.

ALI ABBAS: So we went there. I took him. And my brother who was Shia, who's also a physician at that time came with us. He came with us, and I told him not to call Ahmar Ahmar. I told him to call Ahmar, Amaar.

ROBERT: So Ali and his friend and his brother using this new name got into the morgue where they were taken to a room where everybody sits to look at pictures of people who are dead.

ALI ABBAS: We sat in that computer room they call it, where there are, like, seven computer monitors. And there's someone on the side of the room where he's holding the mouse and he's moving with his finger the pictures, changing the pictures, and people sitting on the ground, probably 35 or 40 other people on the ground looking at the pictures.

ROBERT: Hoping not to see a picture of their brother or their mother or their father.

ALI ABBAS: So whenever there's a picture of one of the relatives you will hear someone crying, shouting, wailing. We were looking at the pictures, looking at the pictures.

ROBERT: Picture after picture after picture.

ALI ABBAS: And, you know, we finally found—reached a decision that his father wasn't among the pictures. And suddenly his father's picture comes out. Then Ahmar started crying and, you know, my brother would say, "Ahmar, don't worry. Ahmar, don't—Ahmar, this is God's decision, this is God's dah dah dah dah dah." And then ...

JAD: He'd say, "No, Ahmar?"

ALI ABBAS: "Ahmar, Ahmar." And I would hit him on his chest. "Don't say this word. Don't say it." Because not only Ahmar will be killed, it will be us as well.

ROBERT: But nobody in the room apparently heard him say Ahmar, the wrong pronunciation. So they got a number from the picture, and then they had to go to a different part of the morgue to actually locate the body and then of course bring it home for proper burial.

ALI ABBAS: So we walked out from the computer room, we went to the refrigerator, which is actually not a refrigerator. It's just hallways. All these bodies dumped on both sides of the hallway. And as soon as you enter these hallways you can barely hold your breath. The smell, the odor is so, so stringent. It's like it's impossible to bear. And the whole ground is full of a thick layer of greasy blood. You know, it sticks to your foot when you walk. It's like squish, squish, squish.

ROBERT: And it was a very long hallway.

ALI ABBAS: Ahmar was—he actually fell twice. We would stop him from falling down, and we would slap him on his face, "Wake up, we gotta keep going." So we would walk all the way down to find all these piles of bodies. Then in one pile, the guy who's wearing boots, the worker there, he would tell us, "I think your father's within this pile." And he's, like, talking normally. He's unbothered by all of this. He threw the bodies from this side and from this side, and then he took Ahmar's father from his arms and he just pulled him from underneath the pile. Ahmar didn't want to believe that this was his father. He didn't want to believe. He said, "I don't know. I don't think this is my father. I don't see him." But the tag number was there.

ROBERT: And because the tag number was there, they knew it was Ahmar's father.

ALI ABBAS: We came out and we thought, you know, that's—that's it. We're gonna take the body and go home. And at that moment ...

ROBERT: They were suddenly approached by two Shia militiamen.

ALI ABBAS: Who were very obvious they are Shiites and they're from the Mahdi.

ROBERT: From one of the most radical groups in Baghdad.

ALI ABBAS: And ...

ROBERT: One of them said, "Let me see your ID."

ALI ABBAS: So Ahmar had to give him his physician's ID.

ROBERT: But that ID had his real name, his Sunni name on it.

ALI ABBAS: He looked at it. "So Ahmar," he said. "Huh."

JAD: He said Ahmar.

ALI ABBAS: "Ahmar. Huh."

JAD: So he knew is what you're saying.

ALI ABBAS: He knew, yes. Yeah, he talked to his friend next to him. They kept whispering to each other about the ID, and realized probably that's the moment when we are all going to die. Yeah, we're done. So immediately, immediately we started talking to them in a very loud voice. "Listen guys, we're your colleagues here. Whatever you need, come to the emergency room, ask for me. I'm Dr. Ali Abbas and this is my brother Hazad Abbas," you know, to show them that we're Shiites. We started talking in a very heavy Shiite accent, you know? "You can come at any moment if you want to the ER. If you have anything just tell us. Let us know. We're your brothers. Help us here."

JAD: And then they waited.

ALI ABBAS: You know, we just kept looking at their eyes, what they're doing. And thank God, they gave us the papers back. We got Ahmar's father out, and he took him and buried him.

ROBERT: Ali Abbas has now left Baghdad. He's moved to Brooklyn, New York, a neighborhood very proud of its mix of races and people from all over the world. But remember, Baghdad was a multicultural city as well for hundreds of years longer than Brooklyn. So I asked him now that you're here, I mean, given what you've seen, what do you think about us?

ALI ABBAS: I would tell you something. The subway is my—I would sit in a subway car, you know, and looking at the people: African Americans, Hispanic, white. I questioned myself. "He's a Jew. He's not a Jew. He's Christian." And I'm looking at the people, and it's exactly this question that comes in my mind: how they're living together? How ...

ROBERT: Does it seem like something that could explode?

ALI ABBAS: Oh, yeah. It's something that I always think. I mean, I look at them, and look at all kind of races, and wonder how can this country hold that together?

ROBERT: That was Ali Abbas, also the translator for National Public Radio.

JAD: Okay. Time to go. Radiolab.org is our website. Radiolab(@)WNYC.org is our email. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Thanks for listening.

[LISTENER: Radiolab is produced by Soren Wheeler and Jad Abumrad. Our staff includes Lulu Miller, Jonathan Mitchell, Ellen Horne, Amanda Aronczyk and Jessica Benkel, with help from Sally Herships. Special thanks to David Shearing, Carey Donahue, Phyllis Glory and Alley Stanton, Stacey Abramson and the Facing History School.]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of mailbox.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.