Aug 19, 2010

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: And I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. Today, our topic is limits.

ROBERT: Limits.

JAD: Limits.

ROBERT: Yep. How far can you take your—your body? We've done that.

JAD: We yeah—we've exhausted that.

ROBERT: I think so. So let's go uptown.

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: To the limits of the brain, to tackle just a piece of that question. Let's just take a look at memory.

JONAH LEHRER: Okay. All right, great.

ROBERT: And we're gonna do that by telling a story.

JAD: A story that we heard from Jonah Lehrer, you know, a frequent guest on the show, author of the books Proust Was a Neuroscientist, How We Decide.

ROBERT: And the story begins in a small town in the old Soviet Union back in the 1920s.

JAD: And it's about a newspaper reporter named Mr. S—at least that's what we're gonna call him.

JONAH LEHRER: Yeah, so Mr. S is a newspaper reporter. And one day his boss starts yelling at him because his boss gives out these assignments, talks to the whole newsroom, and he notices that Mr. S never takes notes. And this drives his boss crazy because his boss is, you know, saying all these things they have to report on, and Mr. S just never writes them down. And so his boss calls him to his office and says, "Are you lazy? Do you not take this job seriously?" And Mr. S responds, "Well, I just remember it all."

ROBERT: And the editor says, "Come on!" And he sort of quizzes him. He says, "What did I assign you yesterday?"

JONAH LEHRER: And his boss gives him this quiz, and sure enough, he remembers everything.

ROBERT: He remembers everything the editor said word for word. And the editor's thinking, "I don't know what's wrong with this guy. I mean, he's not a great reporter, but he has something queer going on in his head. So he decides to send him to a famous medical doctor in Moscow. A.R. Luria.

ROBERT: Who is Luria?

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Luria—well Luria is a classical figure in neuropsychology and in psychology in general.

JAD: And who is this?

ROBERT: Tell us your name.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Elkhonon Goldberg. I'm a clinical professor at NYU Medical School.

ROBERT: Goldberg knew Luria.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Luria was my mentor. I worked very closely with him.

ROBERT: Not only was he a student of Luria's, Luria gave him a present once.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: This is this book. The book about—the original book about this.

ROBERT: This book is one of the great works of early neuroscience.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Given me by Luria. That's him there.

ROBERT: Oh! So we're going to the right guy! You have an autographed copy by the guy.

ROBERT: It is a beautiful and almost novelistic description of what happened to Mr. S.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: And the original title was A Little Book About Big Baby.

ROBERT: Yeah, what is it in Russian?

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Маленькая книжка о большой памяти.

JAD: Okay. So Jonah, this guy, Mr. S, goes to this psychologist Luria. Now what does Luria do with him?

JONAH LEHRER: Luria, during the book, talks about how he wrote random numbers on a blackboard.

ROBERT: Numbers like 1-8-6-4-3. About 50 numbers.

JONAH LEHRER: And asks Mr. S to remember them.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Okay, here we are on page 16. S would study the material on the board ...

ROBERT: For about three minutes.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Close his eyes. Open them again for a moment.

JONAH LEHRER: "Okay, done."

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: And with that would re-log the series precisely. 6-6-8-0-4-3-2-1.

JAD: Wow. That's like a superpower!

JONAH LEHRER: Yeah. And this impresses Luria. He says ...

ROBERT: So he takes it up to the next level.

JONAH LEHRER: Then Luria gives him, you know, this—this—this incredible assortment of memory tasks, you know, everything from memorize Dante's Inferno to ...

JAD: Memorize Dante's Inferno? The whole thing?

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: No, no.

ROBERT: Well, not the whole thing, just the opening stanzas, mostly.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita, Mi ritrovai per una selva oscura ...

ROBERT: But here's the really weird thing. Mr. S does not read Italian, speak Italian. He had no idea what he was talking about. And yet the thing he memorizes, he gets word perfect.

JONAH LEHRER: Yeah.

ROBERT: And not only that, he was tested 15 years after he'd memorized those stanzas, and he still got it right.

JONAH LEHRER: Yeah.

ROBERT: Oh, wow!

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: He remembered everything. He had ...

ROBERT: When you say everything, what do you mean by it?

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: I mean everything, okay? So if he—suppose he interviewed you 10 years ago, he would have remembered the color of your sweater, whether you held the mic in the left hand or in the right hand. He would have remembered everything. I mean everything.

JONAH LEHRER: Luria never talks about a computational limit on Mr. S's memory.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: "As an experimenter, I soon found myself in the state verging on utter confusion, and I simply had to admit that the capacity of his memory had no distinct limits."

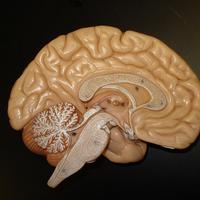

JAD: How can there should be no limits? Because I'm thinking about the size of a normal head. It's like 50 centimeters or something in diameter. The brain is three pounds. It's a very confined little situation. How could there be no limits?

JONAH LEHRER: I wish there was a good answer. Nobody has any idea why it is he had this infinite capability for recall. What it does suggest, though, is that the brain has the capability to store an incredible amount of stuff.

ROBERT: How much stuff, though? How much can you jam into a human brain?

JAD: I don't—I don't think anyone knows. I mean, so let's just stop. Just call it quits. Go to the next—no, no, no. Forget that. In fact, let me take you to a competition which investigates that very question. We're gonna change locations from—where were we just now? Russia?

ROBERT: We were in Russia.

JAD: From Russia in the 1920s to—you ready for this? London, 2009. Here we are at the World Memory Championships.

ROBERT: The world what?

JAD: The World Memory Championships. Just go with me for a second.

ROBERT: Okay.

JAD: So we're in a hotel in central London, and the lobby is crowded with the world's best memorizers.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, interviewer: So what is your name?]

JAD: Got people here from, like, Oman.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Grandhi Rahdj, I'm Dr. Grandhi.]

JAD: Manchester.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Hello, I'm Emile Hawke.]

JAD: Netherlands.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Yeah. Rick D. Young.]

JAD: Even have a team of Chinese girls in the corner doing a cheer.

ROBERT: And what are we doing here?

JAD: Well, the people here are a little bit like the guy you were describing, Mr. S. They are walking experiments in brain stuffing. The difference is they're perfectly normal human beings.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, interviewer: Could start by introducing yourself?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Ben Pridmore: Okay.]

JAD: Like, take this guy.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Ben Pridmore: I'm Ben Pridmore. I'm the reigning world memory champion. I'm 33 years old and I live in Nottingham.]

JAD: Ben can take a string of numbers that is 1,400 numbers long.

ROBERT: Random numbers?

JAD: Random numbers. And he can commit it to memory instantly. He can take a deck of cards and memorize it in 24 seconds.

ROBERT: Wow!

JAD: Yeah.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: We've not actually reached, you know, any kind of upper limit of what it's possible to memorize, yet everybody's still consistently improving.]

JAD: So here's what we did. We—we found a guy.

RONNIE WHITE: Oh, I'm—my name's Ronnie White, and I'm the 2009 USA Memory Champion.

JAD: He's a Navy reservist from Dallas, Texas.

RONNIE WHITE: Matter of fact, I had to get permission from my unit to come here.

JAD: And we followed him around the competition.

INTERVIEWER: What's about to happen?

RONNIE WHITE: Well, the competition's about to start, you know? You know, it's day one. Should be a fun day.

JAD: Because we wanted to know, like, how do you do it? How do you take the limits of a normal brain and completely shatter them?

RONNIE WHITE: So I walked into the room that day wearing my Michael Phelps t-shirt. You know, it said "USA" on the front.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Okay, your one minute of mental preparation time starts now.]

RONNIE WHITE: The final minutes before you start an event, you're sitting in your chair and you're just collecting your thoughts. I put on my military glasses. I got some—they're like Drew Carey's glasses. And I put those on to remind me, hey, remain calm. You know, I wore those all throughout my tour in Afghanistan. And if you're going down a road and—and you're needing to be on the lookout for IEDs, but you're not calm, you're nervous and jittery, you could die. Then I'll put on some noise-canceling headsets. And then I just close my eyes, sit in my chair.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Ten seconds. Neurons on the ready.]

JAD: "Neurons on the ready," they say. "Go!" And at that moment, 60 people turn over papers. On these pieces of paper are numbers.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Six, seven, one.]

JAD: Nothing but numbers. Numbers, numbers, numbers, numbers, numbers forever.

ROBERT: And what are they doing?

JAD: Well, they have to memorize them.

ROBERT: So they're just—you're seeing all these people staring at pieces of paper?

JAD: Yeah. Absolute silence. Heads down, 60 heads down. Staring at numbers.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Six, seven, one.]

JAD: But here's the—here's the interesting thing: in their heads, they're not seeing numbers. Instead, those numbers are turning into ...

RONNIE WHITE: George Bush, Florence Nightingale, Randy Richardson, he's a friend. Barney Fife, a rash, Michael Jordan, Chuck Norris, Donnie Brasco, Bush—no, that was Boy George. Joe T, Martha Stewart, George Michael, Ben Franklin, Chuck Norris, Anne Frank, Indiana Jones, my friend Ronnie, King Tut. I have a person assigned to every number from 0 to 99. And then I have a verb assigned to every person from 0 to 99. And then I have a noun assigned to every digit. So you're just taking person, verbs and objects.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, World Memory Championship 2009: Stop memorizations. Please put the cards down.]

RONNIE WHITE: And you're putting them all together, and they really don't make sense.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, interviewer: What were some of the things? Give me an example of the ...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Ronnie White: The images I saw?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, interviewer: Yeah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Ronnie White: I saw Albert Einstein riding a roller coaster into a bunch of fog.]

[VOICE: Five-nine-three-seven-eight-seven.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Ronnie White: That was one of the images. I saw a Fat Albert cartoon character driving a car.]

[VOICE: Eight-one-nine-nine.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Ronnie White: I saw a Victoria's Secret model, which was one of my favorite pictures. [laughs] I saw a Victoria's Secret model shooting a gun.]

[VOICE: Hey, Ronnie!]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Ronnie White: Stuff like that.]

ROBERT: [laughs] Stuff like that.

JAD: So there seems to be something about turning data into pictures that makes that data etch.

JONAH LEHRER: It becomes easier to hold on to.

ROBERT: Do you have any idea why?

JAD: Do I have any idea why?

ROBERT: Do you? I'm asking.

JAD: No. But Jonah might.

JONAH LEHRER: I don't know. I would just be purely speculating here, but the visual cortex has been hugely enhanced in human evolution. It's, you know, the rear half of our brain because we know that memories—you know, there is no memory center of the brain. It's—it's distributed in our sensory areas. It might make a little sense that given that we've got this huge chunk of visual cortex, that it's easier to store memory there.

ROBERT: Okay. So let me ask you, how did Ron's visual cortex do in the big contest?

JAD: Well, Ron—Ron didn't actually do so well.

ROBERT: He didn't?

JAD: Mm-mm. He was trying to memorize these 12 decks of cards, and he had constructed this whole, like, a stack of pictures, but he—he did them in the wrong order, and he screwed it up.

ROBERT: He lost?

JAD: He lost really badly, unfortunately.

RONNIE WHITE: I was shocked. I mean, I was just shocked. That—that knocked me out of any possible ...

ROBERT: You know who—by the way, who didn't lose? Remember Mr. S, the guy we started this conversation with?

JAD: Yeah, sure.

ROBERT: This is interesting. It turns out that Mr. S also had little pictures and little characters running around in his mind. But unlike Ron, he never asked for the pictures.

JONAH LEHRER: No, he couldn't. You know, even when he wanted not to do it, he couldn't help but do it.

JAD: Meaning what?

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: He was born that way. He had this tremendous memory without any effort and without any mnemonic techniques. This is the point.

JAD: You mean his mind made the pictures automatically?

JONAH LEHRER: Yeah.

ROBERT: Mr. S had a condition called synesthesia, where your senses get kind of tangled up.

JONAH LEHRER: So he heard voices in terms of colors ...

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Right. Colors or voices.

JONAH LEHRER: ... textures ...

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Smells of words.

JONAH LEHRER: And his numbers weren't just numbers. Sometimes he imagines walking through a crowded Moscow street, and the numbers are scattered along the way. And so he describes how I'm walking into the street, there's the number one.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: This is a proud, well-built man.

JONAH LEHRER: Then I make a right turn onto the side street. There's the number ...

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Two is a high-spirited woman.

JONAH LEHRER: Then I make a left turn. There's the number ...

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Three, a gloomy person. Why? I don't know.

JONAH LEHRER: Nobody knows. Nobody knows exactly what accounts for the individual associations of synesthesia. They just exist. But they're this extra scaffold for Mr. S's memory to cling to.

JAD: Wow. So he's like Ron, except he's using all his senses to remember numbers.

JONAH LEHRER: Exactly.

JAD: So getting back to the plot. What did—what did he do with this talent?

JONAH LEHRER: He became a traveling circus freak, basically.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: Yeah. Yeah, professional mnemonist. Yeah.

ROBERT: Mr. Memory.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: He gave up journalism to perform for crowds.

ROBERT: Just imagine it went something—I don't know, like this.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, carnival: Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome the captain of cognition, the master of memory, the spectacular Shereshevsky! [applause]]

ROBERT: Imagine this is a big crowd. He walks on to the stage. He gives them an invitation. He asks them to ...

JONAH LEHRER: Shout random numbers.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, audience: 58! 25! 24! 157! 540! 45! 52! 203!]

ROBERT: Then after a little while, the crowd quiets down and Mr. S would close his eyes and step forward.

JONAH LEHRER: And he would remember them all.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, audience: [gasps] [applause]]

JAD: This was his job?

JONAH LEHRER: Yeah.

ROBERT: And it wasn't just numbers, by the way. He was thrown weird phrases, nonsense sounds, nouns, verbs. And sometimes he'd do four shows a day. And the more he did, the more obvious it became that this business of his, it had a downside. Here's where we're gonna finally reach, maybe, the limits question that we're really examining in this program. He would hear all these nonsense phrases being thrown at him and they would build up in his mind.

JONAH LEHRER: And it's important to note this was incredibly frustrating for Mr. S.

ROBERT: He had a constant stream of memories pouring into his brain. He couldn't get any of it out. And on top of that, as they piled up, the memories began to kind of mush together. One would trigger another and then another and then another.

JONAH LEHRER: It was this suffocating eating web of association.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: The moment he encountered anything, everything even remotely related in his past to that something was immediately evoked in his memory.

ROBERT: For example, let's suppose a man in the audience stands up and he shouts out the word "dog." For a split second, Mr. S sees a dog, which suggests another dog and then another dog. And then ...

JONAH LEHRER: Every dog he ever saw.

ROBERT: And the man suggests not just that man, but the man beside him, other men, men that he knew ...

JONAH LEHRER: All the other competitions where a similar-looking man stood up and shouted something similar.

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: He was barraged. He was deluged. There was all kinds of memories totally unrelated. Everything layered, one layered on top of with the other.

ROBERT: That's horrible!

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: I agree.

ROBERT: Oh!

ELKHONON GOLDBERG: That would be a bloody nightmare.

JONAH LEHRER: The mind isn't just interested in storing information. It really wants to be able to get meaning out of that information, out of those memories. And that actually seems to be turned off, to be inhibited by remembering too much.

ROBERT: In other words, there really is a limit in our heads. It's a different kind of limit, really. Not the limitless ability to remember one number after another, but a precious balance in your head. If you remember too much, you will make no sense of the world.

JAD: It's weird. I've never actually thought of making sense of the world as being an—an act of negation.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: Do you know what I mean?

ROBERT: It's very much that.

JAD: But it kind of makes sense because if you think about, like, living here in New York City. All the people you bump into. If you remembered every freakin' one, like, you wouldn't be able to have a relationship with your wife or your husband or your child, because they'd just be lost in this thick crowd in your head. It's like, "Get out!"

ROBERT: Out! Somehow, that's the balance. The act of forgetting is crucial to create preciousness.

JAD: Although I do wish I had a better memory.

ROBERT: What's your name again?

[RON WHITE: This is Ron White, the memory guy. I'm going to pause for a few and then I will start.]

[PATRICK AUTISSIER: Hi, it's Patrick Autissier. Support for NPR comes from NPR stations.]

[RON WHITE: The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.]

[PATRICK AUTISSIER: Helping NPR advance journalistic excellence in the digital age.]

[RON WHITE: The Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, supporting the performing arts, environmental conservation, medical research and the prevention of child abuse.]

[GUROL SUEL: And the Ford Foundation, a resource for innovative people and institutions worldwide. On the web at FordFound.org.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.