Oct 27, 2016

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

AMY PEARL: Good. Okay.

DAN PASHMAN: Is your mic on?

AMY PEARL: Yeah. I'm getting—this is making me nervous. Maybe I should get my EpiPen.

DAN PASHMAN: Are you allergic to radio greatness?

AMY PEARL: Not that I know of. I haven't been really exposed to it yet.

DAN PASHMAN: [laughs]

AMY PEARL: Anyway, let's go!

DAN PASHMAN: Are we rolling? We're good? We're going?

JAD ABUMRAD: We are rolling.

DAN PASHMAN: Okay.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert Krulwich. This is Radiolab. And today we're gonna begin with a conversation between Dan Pashman …

DAN PASHMAN: Okay.

ROBERT: Host of a podcast here at WNYC called The Sporkful. It's about food. And Amy Pearl.

DAN PASHMAN: Amy?

AMY PEARL: Yes.

ROBERT: A digital producer here at the station who likes food.

AMY PEARL: Mmm.

ROBERT: And the conversation they had was about something that happened to Amy, which she never expected, certainly didn't want, and yet, it could happen to any of us at any time.

DAN PASHMAN: So years ago, before any of this happened to you, just tell me what was your relationship with meat?

AMY PEARL: My relationship with meat?

DAN PASHMAN: Yeah.

AMY PEARL: Well, you know how when you're little and your mom is like, "You can have any special dinner for your birthday?" My dinner was meatballs. And she was like, "Except meatballs. They're so hard to make." So it was pot roast.

DAN PASHMAN: [laughs]

AMY PEARL: And then Peter Luger, you know Peter Luger's?

DAN PASHMAN: Famous steakhouse in Brooklyn.

AMY PEARL: Yeah. I used to go there quite often, and I live there. And I have a Peter Luger credit card.

DAN PASHMAN: Are those hard to get?

AMY PEARL: You know, I don't—I don't know how they give them out but nobody seems to have one. I don't think they give them out anymore, but I mean, I was very into Peter Luger. I was living in Williamsburg, and it just—it opened at, like, one o'clock every day, and you could just walk in at one. They had an amazing bar. There's no tablecloths on the table. These old German waiters, they'd bring out your porterhouse for three. They'd put a little plate upside down and then put the big platter on top of it so it's tilted, and all the juice runs to the end. And then they, like, have this special double spoon thing that they somehow, like, scoop juice onto your steak. And oh, so good!

AMY PEARL: And also, like, the smell of burning fat from a hamburger.

DAN PASHMAN: What about hot dogs?

AMY PEARL: Oh my God. I love hot dogs so much. When you bite into them and they're like, klack, and have, like, a snap. And, like, having a weenie roast out in the open air, it's just—it's like the—oh, God, it's so good. Anyway, I was always very into meat.

DAN PASHMAN: What changed?

AMY PEARL: Oh my God. It was terrible. It was—what happened was I was having this beautiful—it was springtime. I was having a beautiful leg of lamb with some neighbors and we, like, put it on the grill, and it was just a delicious, beautiful dinner. And I had served with it some ramps that I foraged in my mom's yard.

ROBERT: A ramp, by the way, is just a wild onion.

AMY PEARL: And so we had this delicious meal and then, you know, I went home and I was going to sleep at, like, midnight, like, a few hours later. And I just felt weird. I was like, "Ooh, God. Something's wrong. I feel, like, really anxious, like something's wrong with me." And I went in the bathroom and I, like, look in the mirror, and my face was, like, all weird looking, and I was like, I kept laying down and be like, "I'll just sleep it off, whatever it is." But every time I laid down, I felt like I was gonna faint. So, I was like, prop myself up. And I was like, "Ugh!" God, I was having terrible, like, stomach cramps and just like a weird feeling of impending doom, you know?

AMY PEARL: But just like anybody, I'm just like, "Just get a good night's sleep. This will pass." I, like, splashed a little water on my face. I mean, I don't know what made me think this, but I thought, like, maybe a snail, a tiny snail was on one of the ramps that I ate, and it was, like, poisoning me somehow. You know, snails, I mean they probably poison us.

DAN PASHMAN: [laughs]

AMY PEARL: So I called my friends in the morning and I was like, "Hey, how you guys doing? How was dinner?" And they were like, "Oh, it was so great!" And I was like, "Really? It was so great? Nothing weird? Like..."

DAN PASHMAN: [laughs] No horrific panic attacks?

AMY PEARL: And they were like—and they were like, "Oh, that was so lovely. Thank you so much. Let's do it again. Blah, blah, blah." And I was like, "Wow, I really had a rough night." But I didn't think anything of it, and I went on with my life, you know? Just like, whatever. And then about a week or two later, I made some cheeseburgers. And I ate a cheeseburger, and I was watching Goodbye Mr. Chips, a really tear-jerking movie and a good book, too. And about a couple of hours after I ate, I, like, started to feel really weird. Again, I was, like, feeling like I was—like, had to stand up. I was like, "I think I'm gonna faint. I feel really lightheaded. I can't catch my breath. I feel, like, really woozy." But any time I laid down, I really felt like I was gonna faint. So I was, like, trying to stay sitting upright, and I was like, "Oh my God, this is very similar." And I ran into the bathroom and I was, like, looking in the mirror, and lo and behold, I had hives all over my stomach, and then they started coming out on my hands. And I was like, "Oh my God, something's happening." And at one point I did get up and unlock my door, because I did feel like I'm gonna pass out, call an ambulance and then they're not gonna be able to get in. So I mean, I was a little bit afraid of what was happening.

AMY PEARL: And when I woke up in the morning, the first thing I did was Google "Sudden meat allergy," because I was like, "This seems like an allergy," and the only thing that was the same was meat. And I'm going through and, like, the second thing that came up was this article that was like, "Florida Man Has Sudden Meat Allergy." I was like, "Oh my God, I think is it possible I could have this?" And so I made an appointment with my doctor. I brought in the article. I'm like, "I'm going to be this person, but I can do it." I had the article in my pocket.

DAN PASHMAN: What person?

AMY PEARL: You know, the person who goes to their doctor with something I found on the internet.

DAN PASHMAN: [laughs]

AMY PEARL: So I brought the article. It was in my pocket and, like, I got through the whole, like, checkup and I was too chicken. I went—when I was paying the receptionist, I pulled it out and gave it to the receptionist, and I was like, "Could you give this to the doctor?" So that was, like, the best I could do. And then I did call my doctor and had a conversation with him on the phone asking him if I could get tested. And he was like, "No, there's no such thing as a meat allergy. Blah, blah, blah."

PETER SMITH: So some people think allergies are just, like, in your head.

ROBERT: This is science writer Peter Smith. We got in touch with him after we heard Amy's story because Peter is an investigator of many things including strange allergies.

PETER SMITH: And people are like, mushrooms hurt them or they think...

LATIF NASSER: Wi-fi hurts them.

PETER SMITH: Yeah, wi-fi hurts them. And I don't know...

ROBERT: And when our producer Latif Nasser and I got into the studio and we told him about Amy's story. He said...

PETER SMITH: Yeah. All right.

ROBERT: I know exactly who you need to talk to.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Hello?

LATIF: Yeah, hi!

PETER SMITH: Thomas Platts-Mills.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: This is Thomas Platts-Mills. That's right.

LATIF: How are you?

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: I'm very well.

ROBERT: Dr. Platts-Mills is down at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. He's a professor, and he works at an allergy clinic.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: In an allergy clinic, we are constantly sifting through stories, which not only you don't believe, but are actually nonsense. It's simply ...

ROBERT: And he told us in the last 10 years or so, he started hearing lots of stories just like Amy's.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Right.

ROBERT: Somebody shows up at the office convinced that they're allergic all of a sudden for no apparent reason to red meat.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: The first time I heard it was probably as early as 2004.

ROBERT: And every single time he heard the story, he would tell the patient exactly what Amy's doctor told her.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: No.

ROBERT: No way.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: No, no, no.

ROBERT: It's not possible.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Right.

ROBERT: So what was wrong with these complaints, you know, in an orthodox medical way?

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Oh, everything.

ROBERT: Everything.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Adults don't become allergic to something they've eaten for 40 years out of the blue, and certainly not red meat.

ROBERT: So you're basically saying to these patients, "I think you must be making this up, because I can't explain it"

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: I don't use language like that. [laughs] I say, "There, there."

ROBERT: I was trying to give you your inner voice.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Oh, you don't want to know what doctors are thinking in their inner voices. You know, you often think in the middle of an interview, "Is it possible that he's got, you know, some ghastly disease?"

LATIF: Mad cow.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Yeah, you know?

ROBERT: The point is that when he'd hear a story like Amy's, he just...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Didn't believe it.

ROBERT: But then, everything changed. Thanks, oddly enough, to a cancer drug.

PETER SMITH: This new cancer drug called cetuximab.

[NEWS CLIP: In New York today, Martha Stewart was indicted on criminal charges relating to...]

ROBERT: This is the very drug that got Martha Stewart in all that trouble for insider trading.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: You remember that? And went to jail for six months?

ROBERT: Yeah.

ROBERT: Anyway, very promising, exciting new drug. But then...

PETER SMITH: Doctors were giving people this injection, and they would just like, end up on the floor of the doctor's office.

ROBERT: In shock?

PETER SMITH: Yeah, they would be in anaphylactic shock.

ROBERT: Their hearts would start beating faster, they'd get short of breath, they'd get stomach cramps. Their immune system would start to overreact to something new and alien that came in with the drug. Basically, a classic allergic reaction.

PETER SMITH: So the mystery lands on Thomas Platts-Mills's desk.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Yes. So we were asked to look at cetuximab.

ROBERT: To see if they could figure out what was causing the reaction.

PETER SMITH: And he tests two groups of blood: a control sample, and then people that have this allergy.

ROBERT: And he quickly zeroed in on a particular molecule, a sugar that was part of the drug.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: This sugar, galactose-alpha-1, 3. Galactose or alpha-gal.

ROBERT: Alpha-gal?

PETER SMITH: Yeah.

ROBERT: As in a particularly great lady? Better than the Beta or Gamma gals?

PETER SMITH: [laughs]

LATIF: Yeah, it's like alpha male, but alpha female didn't quite have a ring to it.

ROBERT: Anyway, it seemed like alpha-gal was the culprit.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Yeah, and if you'd told me four years earlier that there's a whole lot of people out there who are allergic to this sugar, I'd have thought you would smoking, you know, vaping again.

ROBERT: Because not only does this sugar alpha-gal show up in the cancer drug—and this is where we get back to Amy—it also shows up in the blood of mammals.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: All non-primate mammals.

ROBERT: So every time you eat...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: ...lamb...

ROBERT: ...or...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: ...beef, goat, camel.

ROBERT: Even...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Tripe.

ROBERT: Or...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Pig's kidneys.

ROBERT: You're also eating alpha-gal.

AMY PEARL: So I'm reading this article and it says, like, it's this thing called alpha galactose or alpha-gal or whatever.

ROBERT: So it made no sense that someone like Amy, who'd been eating meat all her life would suddenly somehow be allergic to alpha-gal.

AMY PEARL: I just was like, this was so stupid.

ROBERT: So one day ...

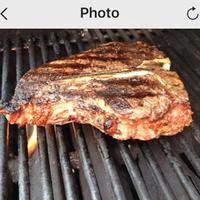

AMY PEARL: It's getting to be barbecue season. I usually have, like, a couple of barbecues where I just do a whole pork butt and a brisket, like hang out all day doing it. And I was like, very wanted to do that. And I was like, "I'm just gonna not eat meat and not even know?" So I was like, "Forget it. My doctor won't test me. I'm gonna test myself." So I was gonna be very careful. I got a thing of Benadryl. And I was like, "I'm not gonna do it alone. I'll do it with my mom." My poor mom. [laughs] And so I went up to my mom's and she's, like, really into food too. So she was like, "Oh, this is so exciting! I got two porterhouse steaks on sale at Stu's."

DAN PASHMAN: [laughs] Did you explain to her what you were testing?

AMY PEARL: Yeah, I did, because I had talked a little bit about it with her. So, like, fire up the grill, do the porterhouse. I even think I, like, Instagrammed it as a joke. Like, "Ha ha ha. This might be the last time you hear from me." But, you know, we're having a nice summer day, just me and my mom having our steak. I only ate, like, a couple bites because I was slightly nervous. And I was, like, sitting in the grass with my dog and reading a book and trying to think, like, do I feel normal? Which, try it, folks. It's hard to figure out. When you start asking yourself, "Do I feel normal? Does this—am I breathing? Does my stomach hurt? Is something wrong?" And I was like, after a while I was like, "I feel pretty good."

AMY PEARL: And the neighbor came over and was, like, chatting with us, and it was in the middle of that conversation where I was like, "I kind of feel like I have to go the bathroom. But maybe I just have to go the bathroom." So I went to the bathroom, and I was sitting there and I was like, "Oh God, something feels bad. I'm—" and then I was like, "Oh God, I definitely—this is not right. Something's wrong." And I went in to get the Benadryl, and I took the Benadryl and I went on my bed in the guest room at my mom's house. I was, like, sitting on there and I was like, "I just don't feel right. Maybe if I just take a deep breath. I'll just stand up. Maybe I'll just put my hands over my head like this. Oh, that does feel slightly better, I think." Then I was finally like, "I think we should go to the hospital."

AMY PEARL: And I went outside. I was like, "Mom, I think you have to drive me to the hospital." She was, like, talking to her neighbor like, "What? Oh my God, honey! What? Oh, let me go change my clothes." Change my clothes. Like, Mom, you know, she's not wearing the hospital-level clothes. So I'm like, "Okay, Hurry up, mom. Mom, are you ready? Mom?" And then I was like, while she was changing her clothes, I suddenly was like, "Oh my God." Got my wallet out and my cell phone and I, like, threw it towards my mom's bedroom door. And I was like, "Here's my insurance card. Call an ambulance!" And I just, like, hit the floor.

AMY PEARL: Eventually, the ambulance arrives and I got stabilized. I was strapped to the thing. I was in the emergency room. Like, they were shooting me full of, I don't know what, epinephrine and adrenaline. And the little, like, 12-year-old emergency room doctor runs in and he was like, "I looked it up on the internet. Alpha-gal. Fascinating!" "What? That's terrible. I've never heard of that. Could it be true?" "Yes, it's true." Like, they're all having this discussion there. Then when I went back to my doctor after that I was like, "Hey just got out of the emergency room because they tested me for alpha-gal and I'm allergic to meat."

ROBERT: So this is an allergy.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Yeah.

LATIF: So all of a sudden, you're looking at the quote "crazies," and they're not so quote "crazy" anymore.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Absolutely. We suddenly had a blood test. And of course, what turned out is all these patients who'd been telling us this story were allergic to alpha-gal.

PETER SMITH: But...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: But...

PETER SMITH: ...it's still like a mystery.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Right. There are patients...

ROBERT: Thomas Platts-Mills couldn't figure out why people like Amy, who had lived for 40 years eating porterhouse steaks at Peter Luger's with a credit card, why would she suddenly develop an allergy now? There has got to be some kind of trigger.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Yes. So we were looking for anything that could explain it.

PETER SMITH: It could be a mold. It could be a nematode.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: A worm or a fungus.

ROBERT: But then he looked again and noticed that all the people who had had bad reactions to the cancer drug...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: They were in a particular area of the country. It was Virginia, North Carolina, Southern Missouri, Tennessee, Arkansas. No cases in Salt Lake City. No cases in Denver. Just smatterings down the West.

ROBERT: So he turned to his technician Jake and he said...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: I said, "You've got to Google every map you can find and say what matches that area?

ROBERT: Creatures or diseases that appear wherever the allergy appears. So Jake starts Googling.

PETER SMITH: Googling and googling and googling. And...

ROBERT: And eventually, he comes across a map that...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Matches where the cases are very beautifully. The maximum area for Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

PETER SMITH: So he made this little map and it's like the shaded dark areas of the country are places with Rocky Mountain spotted fever. And then there's like some stars where, you know, this allergy had appeared.

LATIF: Yeah.

PETER SMITH: And they overlap.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Ah, very interesting.

PETER SMITH: And then all of a sudden it clicks. Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a tick-borne disease.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: This is the distribution of the lone star tick.

ROBERT: And actually, just little before this, it turns out an allergist down in Australia, Sheryl van Nunen...

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: First name Sheryl. S-H-E-R-Y-L. Van Nunen. V-A-N and then N-U-N-E-N. And I'm from the Tick-Induced Allergies, Research and Awareness Center in Sydney, Australia.

ROBERT: She says she was now being visited by all kinds of people who claim suddenly to be allergic to meat.

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: And whenever I take a history, so for example, I'd ask them was there a family history of rhinitis, eczema, asthma, stinging insect allergy, and they'd say they've all been bitten by ticks.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: When we started asking patients, we suddenly heard the stories just out the kazoo.

ROBERT: But at this point, Dr. Platts-Mills, all he has is a map, some stories and a hunch.

LATIF: Right.

PETER SMITH: So...

ROBERT: So what does he do?

PETER SMITH: He decides—well, maybe I'll just do this to myself.

ROBERT: He does what?

PETER SMITH: He decides to test it on himself.

ROBERT: Oh my God!

PETER SMITH: He sort of like denies that he did it intentionally.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: I know I had no intention.

PETER SMITH: I mean, he—I think he also likes to walk and amble and think about things.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Right.

PETER SMITH: So he goes for a long walk along the Blue Ridge Mountains.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: And I knew I wanted to be off trail because I'm actually rather allergic to humans.

LATIF: [laughs]

ROBERT: So he's walking and walking and walking, and along the way...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Ah.

ROBERT: ...he bumps into a whole bunch of ticks.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: And if you walk into a nest of those things...

LATIF: Oh my God, this sounds like a nightmare.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Yeah, absolutely. I got 200 seed ticks.

PETER SMITH: Oh boy.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: And then in November of that year, I was taken out to dinner. And the lamb chops were particularly delicious, and the French wine was delicious. And six hours later, I woke up covered in hives.

PETER SMITH: He's got an allergy to red meat.

ROBERT: All just because of a...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Tick bite.

PETER SMITH: Tick bite.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: That's right.

ROBERT: We'll bite you right back after this.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich. This is Radiolab. Now we go back to Amy just when she's discovered that the allergy to meat that she's developed comes from a tick bite.

AMY PEARL: A tick bite? Hang on a second. Because, like, a few weeks before all this started happening, as I said, I was forging for ramps in my mom's backyard, and I had a tick on my arm.

ROBERT: Now it turns out that not only was that tick bite a terrible thing for Amy, it was a kind of double tragedy.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Attenborough: Hidden from view amongst the trees and in the undergrowth...]

ROBERT: And I think it's only right at this point to back up...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Attenborough: ...is a fascinating world of wonders.]

ROBERT: ...and consider the story from the tick's point of view.

GRAHAM HICKLING: Okay, so I'm Graham Hickling. I am a wildlife disease ecologist at the University of Tennessee.

ROBERT: So I was wondering if you could help us tell the story of, in this case, of the lone star tick that bit Amy.

GRAHAM HICKLING: Oh, yeah, sure. So they start off in this little pile of eggs, perhaps a mass of 2,000 eggs under the leaves.

ROBERT: The proud mom who just gave birth...

GRAHAM HICKLING: At that point, she's just a kind of a withered husk.

ROBERT: Meaning dead. But anyway...

GRAHAM HICKLING: A few weeks later, those eggs will hatch and this mass of 2,000 baby ticks emerge from under the leaves.

ROBERT: And could I see them with my naked eye?

GRAHAM HICKLING: If you ran into a mass of them all up together, you would feel like you've got a little smudge of dirt, and then the dirt starts walking.

ROBERT: [laughs]

GRAHAM HICKLING: And so they'll just climb up and they'll, you know, potentially all be on the same leaf or the same twig looking for something to feed on.

ROBERT: Now one teeny little tiny problem for these teeny little tiny ticks...

GRAHAM HICKLING: Is that they dry out.

ROBERT: So when they come up from under the leaves, they come up...

GRAHAM HICKLING: ...briefly...

ROBERT: ...and then they go back down, get a little water, come back up, get thirsty, go back down...

GRAHAM HICKLING: ...and rehydrate.

LATIF: So they, like, commute?

GRAHAM HICKLING: Exactly. And we refer to the behavior as "questing."

LATIF: Oh, questing!

ROBERT: Questing.

ROBERT: So if you were one of these little baby ticks up questing for food...

GRAHAM HICKLING: While you're up there, you are essentially Velcro.

ROBERT: Because on each one of your little legs...

GRAHAM HICKLING: You have little kind of hook-like structures. And so you're flat against the leaf.

ROBERT: Sort of sniffing in the air with your two little front legs.

GRAHAM HICKLING: That can detect CO2, heat, movement.

ROBERT: So let's say one day you're sitting there on your leaf, and you pick up the scent of a nearby mouse.

GRAHAM HICKLING: Mice are the potato chips of the ecosystem. Everything eats them.

ROBERT: Which means you might be about to have your very first meal. So you...

GRAHAM HICKLING: ...basically stand up...

ROBERT: ...stretch out all your little legs...

GRAHAM HICKLING: ...and do a tick dance. And so it's kind of interpretive dance-like movements.

ROBERT: ...while you're waiting for that mouse to come just close enough that you can grab onto it. So you're dancing and you're waiting, and you're dancing and you're waiting, and you're dancing and you're waiting, and you're dancing and you're waiting.

GRAHAM HICKLING: To be honest, you are probably going to wait your entire life and die unfulfilled, because there are 2,000 of you starting off, and a stable tick population there's only going to be two of you that survive.

ROBERT: Oh my gosh!

ROBERT: So 1,998 little baby ticks are born...

GRAHAM HICKLING: ...and then that's it for them.

ROBERT: But let's say that you're one of the lucky ones. And one sunny day, there you are hanging out on your little leaf when you detect two incoming mammals. One is a 40-year-old hominid, the other is her dog. So you perk up, you thrust your legs out...

GRAHAM HICKLING: ...wave, do the tick dance.

ROBERT: And say that you're waving and you're dancing and you're hoping and you're waving and you're dancing and you're hoping and you're waving and you're dancing and you're hoping, and slowly, the dogs getting closer and closer and closer. And you reach out with one of your tiny little limbs so you can grab on and eat and survive. But...

AMY PEARL: But the reason that tick ended up on me was I slept in bed with my dog naked. I mean, she's always naked, but I was also naked. I mean, that's not gross. I mean, does that sound weird?

ROBERT: No, but how do you know that's when it happened?

AMY PEARL: Because I know that, like, I did a good tick check on myself and I took a shower and everything. And then in the middle of the night, I woke up with an itching sensation. And I went to the bathroom, and I couldn't really see what was on—like, something was on the back of my arm, and it was a tick.

ROBERT: So as the tick is biting into Amy, what is it giving Amy that's gonna make her allergic to meat?

PETER SMITH: Well, actually, I need to stop you there, Robert.

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: Hmm, difficult one, Robert.

PETER SMITH: I don't know the answer to that. Hmm.

ROBERT: That's Peter Smith, and...

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: Well...

ROBERT: ...rejoining us is Sheryl van Nunen, the scientist.

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: It's all up for speculation.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: We don't really know. But here's the theory. So...

ROBERT: Normally, when you eat a piece of meat, you put alpha-gal in your stomach and your stomach digests it, and it's in your body, and it's no big deal.

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: But the tick cunningly...

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: ...will drill into you, poke into you...

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: ...and injects...

PETER SMITH: ...its saliva.

LATIF: We'll call that "tick spit."

PETER SMITH: ...tick spit into its victims.

ROBERT: Straight into its victim's largest organ...

PETER SMITH: ...the skin.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: And tick spit has an anti-clotting factor, an anesthetic, anti-inflammatory compounds.

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: And...

ROBERT: ...we think...

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: ...the alpha-gal.

ROBERT: Now Peter says the thing about the skin is...

PETER SMITH: ...the skin is like this enormous, like, surveillance system.

ROBERT: It's always on the lookout for invaders. So when the alpha-gal comes through your skin covered by all that bad, bad tick spit stuff...

PETER SMITH: That's gonna really, like, set off your immune system.

ROBERT: The immune system freaks out.

PETER SMITH: Like, oh! Uh-uh!

ROBERT: And the alpha-gal, covered now in bad spit almost sort of...

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: ...by mistake...

ROBERT: ...gets labeled bad. And now it's on the bad guy watch list. So...

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: ...therefore...

ROBERT: ...the next time you eat meat...

SHERYL VAN NUNEN: ...the meat comes in...

PETER SMITH: ...and then...

ROBERT: ...the body unleashes wave upon wave upon wave of chemical attacks...

PETER SMITH: ...to do battle against this alpha-gal.

ROBERT: And this reaction gets way out of hand. You got so many antibodies multiplying, multiplying, multiplying, multiplying, making you—rather in this case, Amy, feel just horrible.

PETER SMITH: Right.

AMY PEARL: I mean, it's very weird. It sounds like a science fiction movie. It sounds like the beginning of a science fiction at least kids' book, let's not go to movie. But, like, it's just strange.

ROBERT: Which all goes to say that this really is a kind of double tragedy for Amy and her tick.

PETER SMITH: Yeah, because ticks didn't evolve to bite humans.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Right. We're a mistake.

PETER SMITH: Like, we have opposable thumbs.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: We're either gonna pull them off...

AMY PEARL: I actually woke my mom up, and she helped get it off.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: ...or if they drop off, they're gonna drop off in an airport terminal, or a Walmart car park or somewhere like that.

ROBERT: Or a shag carpet.

THOMAS PLATTS-MILLS: Or a shag carpet indoors. And—and they're doomed.

ROBERT: And for us, well, we lose something that, historically anyway, is a big part of who we are.

PETER SMITH: Yeah, because we have—we adapted in the grand evolutionary scheme of things to, like, eat flesh, to eat meat.

LATIF: Yeah.

PETER SMITH: Yeah.

AMY PEARL: I mean, I'm actually sitting here picturing a steak. But actually the thing—I mean, hot dogs. Like, wrap ramps around a weenie and roast. Yum, that sounds so good, my mouth's watering. [laughs] Weenies and ramps.

DAN PASHMAN: Yeah.

AMY PEARL: But I am going my allergist tomorrow because I did—you know, I was reading about this allergy a lot when I first got it, and I read that for some people, the allergy can fade away. So I'm gonna get a blood test to see what my blood level of alpha-gal is. So I'm a little...

DAN PASHMAN: So what are you hoping for tomorrow?

AMY PEARL: I want to be normal again.

ROBERT: That was the end of the Dan and Amy conversation. She was gonna go to the doctor, get herself tested, find out whatever. So we asked her back in...

AMY PEARL: Okay.

ROBERT: ...to find out what happened.

AMY PEARL: So I actually did get an appointment with my allergist. Dr. Corn. [laughs] Her name is Dr. Corn. She's really nice. So I got the appointment, I got the blood draw, whatever. And a few days later, my doctor called me and she said that my numbers were still really high. And I was like, "Well, how high are they?" And she was like, "Three." And I was like, "Three? That's not high." And she's like, "They're supposed to be, like, one or something." So they had gone down, but they were still, you know, many times more than they should be. So...

ROBERT: But when you left and you were waiting for the call, were you waiting with the hope that you would soon be eating a bit of hot dog?

AMY PEARL: I mean, honestly, I was hoping no.

ROBERT: No?

AMY PEARL: No.

ROBERT: Wait a second, you are the big, the great...

AMY PEARL: No, I was afraid that she would be like, "Oh my God, your numbers are so low. I think you could probably eat meat. And let's do a food challenge." And I would be like, "Ahh!" Because, like, that's such a scary memory. Yeah, I don't—you know, actually just the other night I was eating at an Indian place and I was eating vegetarian but, like, I felt something and I pulled it out, and in the dim light of an Indian restaurant—like, why are they all lit like that? I was like, "Was this bacon?" And I suddenly—you know, like you just get this drop in your stomach and I'm like, "What time is it? Four hours from now if I—" and, you know, because there's something about it being delayed that makes it so difficult. It just is like...

ROBERT: Like a suspense movie where you're the victim.

AMY PEARL: It's like it could happen in the next three hours. Or maybe not. I don't know. I mean, honestly, the only thing that—the real reason I want to be able to eat meat is so that I will be prepared to eat it in case of emergency. I mean, I went on a canoe trip in the Adirondacks and I was like, "Well, what happens if I get stranded out here? And like, what if I have to hunt, but I can't even eat meat? I would have to hunt fish. But then when the lake freezes over, what would I eat? I can't survive. Something's wrong with me!" I feel evolutionarily challenged. This is what I think about before I go to bed every night: would I be able to survive if I had just what's on me right now: a pen, underwear, my dog? And so I mean, that's a real issue. It's not a real issue, obviously. It's never gonna happen, I live in Brooklyn. But I do, for some reason, I always think, like, I want to be prepared in case. But I don't think I would go back to eating meat, necessarily.

ROBERT: Like, you are still more frightened than game, so to speak.

AMY PEARL: Well, also, like, I wish I could be a vegetarian for ethical reasons because it's not so much just the eating meat, but just like, you know, the factory farming and that kind of stuff, so I feel, like, morally superior now. I can be like, "Well, I don't eat red meat." Of course, I'm forced to not eat it, but at the same time I would if I had the—if I had the willpower, I'd probably go that way anyway. And then also, I think it's great. It's like, we're all evolving to be on this planet, which is getting harder to be on. And we know that meat takes a lot of resources. And, like, now I don't—now I'm not doing that. So, like, the tick is helping me evolve into a better human being.

ROBERT: Like, so one could, instead of thinking of the tick as your teeny weeny irritating enemy, you could think of it as a guiding light, making the world safer to share with your fellow Earthlings.

AMY PEARL: Yeah.

DAN PASHMAN: So you may have lost your relationship with meat but at least you have your moral superiority.

AMY PEARL: Yeah. I mean, I am superior.

DAN PASHMAN: [laughs]

AMY PEARL: Yeah.

ROBERT: So huge thanks to Amy Pearl for telling a story which never stopped—never stopped being scary and wonderful. And to the fellow who brought her into the room, Dan Pashman, whose podcast, The Sporkful, it's all about food in every conceivable way. Like, he talks about eating it, preparing, it worrying about it, as you've heard, getting sick from it, getting fat from it, whatever. And you can find his show on iTunes or Stitcher or on the internet at Sporkful.com.

ROBERT: And this story was produced by Annie McEwen and Matt Kielty, with reporting help from Latif Nasser. See you next time.

[ANSWERING MACHINE: Received Thursday at 9:50 pm.]

[DAN PASHMAN: This is Dan Pashman from the Sporkful podcast.]

[AMY PEARL: Hi, this is Amy Pearl. I'm allergic to meat.]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: And I'm Susie Von Eggers, Amy Pearl's mom. Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad.]

[AMY PEARL: Jad Abumrad.]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design.]

[DAN PASHMAN: Soren Wheeler is senior editor.]

[AMY PEARL: Jamie, Jamison York is our senior producer.]

[DAN PASHMAN: Our staff includes: Simon Adler...]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: ...Brenna Farrell...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...David Gebel...]

[AMY PEARL: ...Matt Kielty...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...Robert Krulwich...]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: ...Annie McEwen...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...Latif Nasser...]

[AMY PEARL: Malissa O'Donnell, or Melissa O'Donnell...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...Arianne Wack...]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: ...Arianne Wack...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...and Molly Webster.]

[AMY PEARL: With help from Tracie Hunte...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...Nigar Fatali...]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: ...Phoebe Wang...]

[AMY PEARL: ...Katie Ferguson...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...Alexandra Leigh Young...]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: ...W. Harry Fortuna...]

[DAN PASHMAN: ...and Percia Verlin. Percia Verlin.]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: Percia Verlin.]

[AMY PEARL: And Percia Verlin!]

[DAN PASHMAN: All right. That's like all the options I could come up with.]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: Our fact-checkers are Eva Dasher...]

[AMY PEARL: ...and Michelle Harris. ]

[DAN PASHMAN: Yeah, all right. I think I got that one. [laughs]]

[SUSIE VON EGGERS: Bye bye.]

[DAN PASHMAN: Okay, bye.]

[AMY PEARL: Good night.]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

AMY PEARL: If I get, like, cut off from the group when I'm out on a tour of the woods or something, and I have to sleep overnight and I could eat, like, a frog, a bug, but I couldn't eat, like, a squirrel, a mouse. I guess I could eat a bird. I mean, I don't know.

SOREN WHEELER: You know, there's another option too, thoough, Amy.

AMY PEARL: What? Kill myself.

SOREN: No. But the alpha gal's in all mammals, but not in primates.

AMY PEARL: I know. That's so—like...

SOREN: Just sayin'.

AMY PEARL: A chimp burger? No.

ROBERT: Well, maybe think even more darkly.

AMY PEARL: A human. Another human? Baby?

SOREN: Baby? [laughs]

ROBERT: I didn't say baby! Just a good old ordinary cannibal night.

AMY PEARL: Yeah, but if I'm really gonna go for it, it's gonna be a baby. Turkey meatballs are [bleep] awesome.

ROBERT: [laughs]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.