Aug 6, 2015

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

JAD ABUMRAD: So okay, you ready?

ROBERT KRULWICH: Mm-hmm.

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab.

ROBERT: And we're getting ready for—well, this whole podcast you're about to hear is an invitation for you to join us in the next podcast. We will be going ...

[staff singing Happy Birthday]

JAD: [laughs]

ROBERT: Not a second year! This is not—I hate Facebook. I hate that everybody knows this, And there's so many of them! Jesus!

[staff singing Happy Birthday]

ROBERT: You, ladies and gentlemen, are witnessing the death of privacy.

[staff applauds]

JAD: [laughs]

JAD: Yeah. So that happened. We thought we'd throw it in. Anyhow, back to the flow.

ROBERT: So it's I'm Jad, I'm Robert.

JAD: This is Radiolab.

ROBERT: And this particular episode is more or less an invitation for you to get ready for the next episode.

JAD: Yeah. Today we have a preview of an episode that we are working on furiously right now about the periodic table of elements. We're gonna tell individual stories about the different elements, and those stories are gonna take us into outer space, into deep, man-made holes in the middle of America, into our cells. All kinds of places.

ROBERT: So this week we decided to make a small telescoped preview in which we go to one apartment in one building in the city of New York, occupied by the rather singular Dr. Oliver Sacks.

JAD: [laughs] We should say this was a visit we paid to him about six, seven years ago, I think. And this is the story that, in a very real way, inspired us to do this upcoming episode about the elements.

ROBERT: And we also know, by the way, that Oliver isn't feeling so well right now, which makes it particularly wonderful to hear him enjoy.

JAD: Off we go.

OLIVER SACKS: I think there's always been a desire to somehow categorize and classify the world around us.

ROBERT: Remember when you were in, I don't know, when it would be, like in eighth grade, when they—when the teacher comes in in general science and he pulls down the periodic table of elements.

JAD: Oh yeah, sure. I mean, that was one of the first times where I was like, "Yeah, I don't want to be a scientist."

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: It's not for me.

ROBERT: But for kids who love this kind of thing—take Oliver Sacks, for example.

SOREN WHEELER: Jad, you should come in.

JAD: I should come in? Okay.

JAD: Yeah, so a couple years ago, we had went to talk to Oliver Sacks about something. Well, it was actually mostly you that was gonna talk to him and I was just tagging along for the hell of it.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: And for some reason, we ended up in his bathroom.

OLIVER SACKS: I tend to read a little bit on the toilet.

JAD: Maybe to look at a book or something?

JAD: He seems to have facts and figures in this as well.

JAD: There's a lot of us in there.

JAD: I'm sorry.

ROBERT: Sorry.

JAD: And that's when we noticed ...

ROBERT: Oh you've got the periodic chart in the bathroom.

OLIVER SACKS: In every bathroom.

ROBERT: He had a periodic table of the elements on the wall in the bathroom.

JAD: We thought, wow, how funny! Periodic table in the bathroom. But then he said, "Well, you know, if you go out into the couch, you'll see ..."

OLIVER SACKS: Periodic table cushions.

JAD: ... some cushions embroidered with the periodic table. And then he took us to his bedroom.

OLIVER SACKS: Although I don't usually take people into my bedroom.

ROBERT: Oh, we'll come. [laughs]

JAD: Where he showed us his periodic table comforter.

ROBERT: [laughs]

OLIVER SACKS: I tend to sleep here, right under tungsten.

JAD: But the cool part was when he took us to the living room where you had this ...

ROBERT: Well, describe what is before us here. It looks like an altar.

JAD: It's like a little dictionary stand, on top of which was a beautiful mahogany box.

OLIVER SACKS: A fine wooden box.

JAD: About the size of a backgammon set.

OLIVER SACKS: Called periodic table of the elements.

ROBERT: It is a very fine wooden box.

OLIVER SACKS: And if you care to open it.

ROBERT: It's made of some sort of fine wood.

OLIVER SACKS: It comes from Russia.

ROBERT: Is there a trick to opening this? Ooh!

ROBERT: Okay, we've all seen the periodic table, you know, on a chart, but in Oliver's box, there, there were the actual elements.

ROBERT: These are all these—we have here, like, 90-some odd little—little tubes.

OLIVER SACKS: Little samples.

JAD: Little teeny vials.

OLIVER SACKS: Of almost all the elements. Silver, arsenic, bismuth, cobalt, oxygen, copper, hydrogen, phosphorus, iron, manganese, mercury, nitrogen, molybdenum, gold. Since I am, for example, having my 72nd birthday tomorrow, and element 72 is hafnium, there is a little hafnium.

ROBERT: Two little rocks. Here's what—here's what they sound like if you rattle them.

OLIVER SACKS: I have coming to me—I hope it arrives today—an ingot of hafnium, which will be very much more satisfying.

ROBERT: [laughs] What would you do with an ingot that you can't do with the two little pebbles?

OLIVER SACKS: I'll be able to hold it in my hand. My first love of chemistry had to do with the sensuous. Here, one of the liquid elements, bromine. I loved the colors.

ROBERT: Brown, faintly brown fluid-y thing.

OLIVER SACKS: The luster. Pale golden mercury. Very, very beautiful. The physical properties.

ROBERT: This is a gas trapped in a little vial.

OLIVER SACKS: Yes. One wouldn't want to drop that.

ROBERT: Why not?

OLIVER SACKS: Well, it's not good to breathe.

JAD: Can I just jump in here for a second?

ROBERT: Sure.

JAD: Because I—I really need to jump in. [laughs] But the thing that's really crazy about that box—and this you don't get from looking at a periodic chart on a wall, is that all those elements ...

OLIVER SACKS: Lithium, beryllium, boron, carbon, nitrogen ...

JAD: ... that's like the world. I mean, everything that we can see and perceive, this table right here, the teeth in my mouth, the sky, the ocean, the mountains, it's all made of some combination of elements from that box. And the box itself gives it all a deep, deep order.

OLIVER SACKS: I had noticed myself—one can't help noticing that the elements are organized in a very special sort of way. For example, may I?

ROBERT: I have managed to not notice. I find it a little odd that you could organize them at all. I don't even know how to begin the process of figuring out they're related in some way.

OLIVER SACKS: Well, then you are sort of recapitulating what everyone felt in the early days.

JAD: Of course, in the really early days, people thought there were just four elements.

OLIVER SACKS: The ancient notion of elements took the form of earth, air, fire and water. Basically, the thought that the whole world could be composed of these four ingredients in different ways.

JAD: But then, in the 18th century—we're skipping ahead a bit—chemists began to break things down into smaller pieces. Like, wind became ...

OLIVER SACKS: Gasses like oxygen and hydrogen and nitrogen.

JAD: And earth got divided up into things like ...

OLIVER SACKS: Sulfur, phosphorus, iron.

JAD: And eventually, chemists got all the way down to the root, which was the atom. That's really what an element is, it's a particular kind of atom. The problem was though, when chemists began to sort of measuring these atoms, they found that they were all different sizes and types. Like, one would be heavy, another would be light. A third one would be really friendly and likes to link up with other atoms, whereas the fourth would be a loner. And they would come in combinations like: heavy-friendly, heavy-shy, light-friendly, light-shy. What was the pattern? That was the question. Could they fit all of these differences and similarities into one big schema?

OLIVER SACKS: Since we mentioned his name, let me here show you a picture of the ...

JAD: Here's where we get to Oliver's hero.

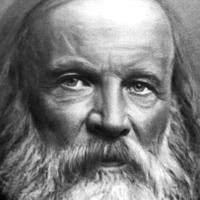

OLIVER SACKS: The siberian bigamist, as he was called.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: That would be Dmitri Mendeleev.

OLIVER SACKS: The great Mendeleev, whom we will talk about.

ROBERT: Oliver has a black and white picture of him on his kitchen cabinet.

ROBERT: This man is not gonna win any beauty contests.

OLIVER SACKS: No. He looks like a mixture between Rasputin and—who do I mean?

ROBERT: Well, you mean he has a big nose, a shaggy, slightly unkempt white beard, a mustache that goes all over the place, piercing eyes, thick eyebrows, and looks like he's in a hunchback position. Generally, if you met him on the sidewalk, you'd probably want to walk around him.

OLIVER SACKS: [laughs] Yeah. He didn't believe in wasting time going to a barber.

ROBERT: Let me just ask you as to the degree of your passion. When you look at this man, do you think he's a beautiful-looking guy, or do you see what I see?

OLIVER SACKS: I think Mendeleev had a beautiful mind.

ROBERT: And when that mind gets on a train—and it was a long, long, long ride from Irkutsk to Moscow—strange things will happen, as you're about to hear. We'll be right back.

[LISTENER: My name's Elise, and I'm calling right before going to bed in Des Moines, Iowa. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org.]

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab.

ROBERT: And we're gonna go back to Oliver Sacks talking his hero Dmitri Mendeleev, now about to take a trip.

OLIVER SACKS: Okay, in 1860, around 1860, there were trains going all over Russia. And Mendeleev could afford to take trains, he was often on enormous journeys. And to while away the time, since he couldn't do chemical experiments or whatever, he would take playing cards with the name of various elements, their chemical and physical properties, and he would play what he called chemical solitaire.

ROBERT: Sorting them for likeness or sorting ...

OLIVER SACKS: I'm afraid I don't know the details.

JAD: But you know what? We can imagine, right?

ROBERT: Sure.

JAD: So let's just say he's sitting there on the train. He's looking out the window. He sees trees made of carbon, a lake made of hydrogen and oxygen.

OLIVER SACKS: Oxygen.

JAD: Behind that, a mountain.

OLIVER SACKS: Mountains here.

JAD: Made of silica.

OLIVER SACKS: Silica.

JAD: And he's shuffling ...

OLIVER SACKS: Their properties and their atomic weights in his mind.

JAD: Wondering ...

OLIVER SACKS: How do these things go together?

JAD: What's the pattern? And he's shuffling.

OLIVER SACKS: I'm shuffling.

JAD: Shuffling.

OLIVER SACKS: Shuffling.

JAD: Shuffling. Shuffling. Shuffling.

OLIVER SACKS: Shuffling.

JAD: And he did this for years. Until one night—and this we think is true.

OLIVER SACKS: In February of 1869, he is said to have had a dream.

JAD: In his dream, all the atoms of all the elements of all the world—the fat ones, the small ones, the dense ones, the heavy ones, the friendly ones, the shy ones, they all began to dance in his mind, and then they snapped into a grid.

OLIVER SACKS: He awoke with a vision of the periodic table.

ROBERT: This is one of those [angelic singing] dreams?

OLIVER SACKS: Which he then wrote on the back of an envelope.

JAD: The thing about what he wrote on the back of that envelope is that it starts out so simply. Left to right, the atoms just get heavier and heavier and heavier.

OLIVER SACKS: Heavier, heavier, heavier.

JAD: But every so often—and this is what he intuited in his dream, is that while they're getting heavier, there are other traits, like whether they're shy or magnetic or whatever, those traits repeat.

OLIVER SACKS: Periodically change back again.

JAD: And every time they do, they start a new row.

OLIVER SACKS: The properties repeat again.

JAD: Out of this simple, repeating structure.

OLIVER SACKS: Anyways ...

JAD: Hush, Mendeleev! You get a table that you can read in a million ways. There are so many ways to read this table.

OLIVER SACKS: I think I'm going to call this the periodic table.

JAD: That if you use your imagination, you can see yourself in there.

OLIVER SACKS: I was a rather shy kid with difficulty forming relationships, and I sometimes compared myself to the inert gasses.

ROBERT: Inert gasses are very isolated. They react with nothing.

OLIVER SACKS: Because I felt they too had difficulties forming relationships. But I did ...

ROBERT: He has now left the chair and has moved to the library. He's taking out a hugely thick—actually a dangerously thick book.

OLIVER SACKS: This is The Handbook of Physics and Chemistry. As you see, it has 5,000 pages. I had a smaller version as a boy. And from brooding in this book, it seemed to me just possible that one of the inert gasses—xenon—might be seduced into combination by the most active element of all, which was fluorine.

ROBERT: This lonely, lonely gas might find a partner somehow. Did they ever get together?

OLIVER SACKS: In fact, it came to me with great joy when I found out in the 1960s that actually a Canadian chemist had in fact made a fluoride of xenon.

ROBERT: Ah! Yes, elemental love.

ROBERT: And speaking of love, he then took us ...

OLIVER SACKS: I think let's come here one sec.

ROBERT: Where are we going?

ROBERT: ... to the living room. And he showed us a small painting. In the painting, there was this dramatic figure of a bearded, scowling character on the side of a mountain holding two stone tablets over his head. And the sky was filled with lightning. And who was it? It was Dmitri Mendeleev!

OLIVER SACKS: When I heard of how Mendeleev had discovered the periodic table, I imagined Mendeleev as a sort of Moses, going up to a chemical Sinai and coming down with the tablets of the periodic law. And when I mentioned this fantasy to Peter Selgen, my friend, an artist, he did this imaginative picture of a young Mendeleev, the peaks of a chemical Sinai behind him, holding aloft the tablets of the periodic table.

ROBERT: Which raises maybe the deepest question of all: did Mendeleev think this up and impose it upon the world? Or was this pattern always there? In which case, Mendeleev just removed the veil and said, "Oh, there you are."

OLIVER SACKS: Is the periodic table discovery or an invention? Is it a human construct, or is it a revelation of the cosmic or divine order? Is it, so to speak, God's abacus?

JAD: Okay, so that was our visit with—how did I just get carried away with the sound?

ROBERT: Yes, it is a little bit closet cluttered, but still ...

JAD: It was a long time ago. It was a long time ago.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: Anyhow, that was our visit to Oliver Sacks, and also a preview to an upcoming episode that we're making right now about elements—which we're really excited about.

ROBERT: Hope you'll be back for that. In the meantime, I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: This is Radiolab.

JAD: Thanks for listening.

[LISTENER: Hi, this is Jemina calling from Saudi Arabia. Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad. Our staff includes Brenna Farrell, Ellen Horne, David Gebel, Dylan Keefe, Matt Kielty, Andy Mills, Latif Nasser, Kelsey Padgett, Arianne Wack, Molly Webster, Soren Wheeler and Jamie York. With help from Damiano Marchetti, Molly McBride-Jacobson, Alexandra Leigh Young, Cathy Tu and Simon Adler. Our fact-checkers are Eva Dasher and Michelle Harris.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.