Dec 18, 2020

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey. It's Jad. Before we start today's show, I want to take a minute to talk to you guys. Every month, millions of people listen to this show, and we are so grateful for that. But as you probably know, Radiolab is public radio. Our show, all the journalism we do, is funded by you. And all the work we did this year, our series "The Other Latif," which took three years to make, all the reporting we did on COVID, on vaccines, on policing, you made that possible. We would not have a show without you.

JAD: So we need your help right now. The situation we're in at Radiolab is that millions of people listen to RADIOLAB every month, but only a teeny-tiny percentage of those people actually give. Less than one percent of our listeners donate to support the show. Less than one percent. I know we can do better than that. So here's the challenge: we want to see if we can get 5,000 new members to donate to Radiolab by the end of 2020—5,000 new members. Help us out. Go to Radiolab.org or text the word RADIOLAB to the number 70101. If you have been moved or inspired or thought about the world in a new way because of something you've heard on Radiolab, please support the show. Support the journalism we do. Help us meet this goal, 5,000 new people by the end of 2020. I think we can do this.

JAD: And, look, this year has been a [bleep] sandwich. It really has, so we're gonna try and bring a little bit of joy. We want to invite you to hang out with us. We're gonna be hosting a virtual trivia night soon. It's a little dorky, but I think it's gonna be super fun. And we want you to play along with us. Here's the deal. If you become a sustaining member, like if you donate $10 a month, $15 a month, whatever makes sense, we'll invite you to join us. It's gonna be fun. If you're already a sustaining member, you're gonna get an email with the details. But join us. Play some trivia. Who's gonna win? Will it be Lulu, Latif? Will it be you?

JAD: So please, go to Radiolab.org, or text the word RADIOLAB to the number 70101 and make a year-end donation. Help us get to this goal of 5,000 new members. And if you become a monthly donor, you can play some trivia with us. All right. Thank you, all of you. You are the reason we do what we do. You're the only reason we can do what we do. Now for the show.

LULU MILLER: Before we start, just letting you know there is some explicit language in this story.

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

LULU: Hello, this is Radiolab. I'm Lulu Miller. And today we have a story from reporter Tracie Hunte.

TRACIE HUNTE: Mm-hmm.

LULU: Where does this story start?

TRACIE: So I'm gonna start you off in New York City. June 25, 1989. It was the Gay Pride parade, but it was also the very first time that David Robinson ever laid eyes on Warren Krause.

DAVID ROBINSON: I noticed this guy I thought was incredibly hot marching by with a group of people. He was shirtless and muscle-y. And he had blond hair, but it was buzzed, like, really short except these two—like what Wolverine had. [laughs]

TRACIE: Okay.

DAVID ROBINSON: They were almost like these little wings up there.

TRACIE: [laughs]

DAVID ROBINSON: He just looked amazing. I remember just thinking, "Oh, my gosh!" But, you know, he was marching by with a group of people. And I remember thinking, "Oh, well. I'll never see him again."

TRACIE: But the next day, David was at an AIDS activist meeting ...

DAVID ROBINSON: And who should be in the front row but this guy? [laughs]

TRACIE: Oh!

DAVID ROBINSON: So yeah. And he invited me to have lunch with him the next day at the apartment where he was staying. And I did go over there, and we didn't, in fact, have lunch.

TRACIE: [laughs]

DAVID ROBINSON: But we had a lovely, lovely time.

TRACIE: Right away, David was like, "Okay, this is it. You're the one."

DAVID ROBINSON: He had grown up on a small dairy farm in Connecticut. It had been a very joyless and sometimes abusive upbringing. He was kicked out at 17 for being gay, and he ended up having his own—gosh, I don't know, just unique way of being in the world. So it's a little hard to talk about because I feel he got cheated so, so badly.

TRACIE: Warren had told David when they first got together that he was HIV-positive.

DAVID ROBINSON: And it was less than half a year after we moved out to San Francisco that the infections started coming fast and furious. By the last, you know, several months of his life, he was just, you know, pretty much homebound. Last two months he had dementia. The last thing he got ended up causing dementia, and he was—he was in the hospital for much of that time. I took him home. His last months until he had dementia, he was really angry.

TRACIE: David and Warren would sit around their apartment talking about that anger, and talking about the fact that they both knew Warren was going to die.

DAVID ROBINSON: You know, we would talk, and he would express that it was his wish to, you know, make a difference beyond his death.

TRACIE: Warren died April of 1992. You know, this was a moment when the AIDS epidemic had been going on now for about 10 years. Research into treatments had basically stalled. There was no cure in sight. More and more people were getting sick and dying.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Larry Kramer: We are in the middle of a fucking plague.]

TRACIE: And it looked like the Bush administration was just not paying attention.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Larry Kramer: 40 million infected people is a fucking plague. And nobody acts as it is!]

TRACIE: And people like Larry Kramer, who co-founded ACT UP, an activist group that David was a part of, they were at their wits' end.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Larry Kramer: We are in the worst shape we have ever, ever, ever been in.]

TRACIE: They had spent years protesting and demonstrating, and just trying to get people to pay attention, trying to get the government to just do something.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Larry Kramer: Nobody knows what to do next.]

TRACIE: And that was David's question, too: what do I do next? What would Warren want me to do?

DAVID ROBINSON: He wanted to be able to continue to make a difference even after he died.

TRACIE: And so David was sitting in their San Francisco apartment alone with a box of Warren's ashes.

DAVID ROBINSON: And inside was just, you know, the plastic bag with the ashes and bone chips, and ...

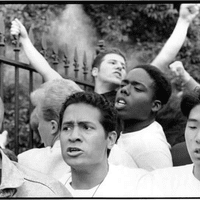

TRACIE: And eventually, he decided that he needed to use what was left of Warren's body to make people pay attention. So in October of 1992, David and about 150 other people, many of them members of ACT UP, met in DC, right in front of the Capitol.

DAVID ROBINSON: You know, I remember lining up with these other people. And some were people I knew very well from ACT UP, and some were people I had never met.

SHANE BUTLER: I mean, it was so visceral.

TRACIE: Shane Butler, a student at the time ...

SHANE BUTLER: The drama and the people.

ALEXIS DANZIG: I remember it being hot.

TRACIE: Alexis Danzig. She had lost her father to AIDS.

ALEXIS DANZIG: And the crunch of the gravel under our feet as we walked down the Mall.

TRACIE: They started marching down the path along the DC Mall, and as they marched, they started to chant.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: Bringing the dead to your door. We won't take it anymore. Bringing the dead to your door ...]

TRACIE: "We're bringing our dead to your door. We won't take it anymore."

DAVID ROBINSON: One of my strongest memories is just of how sore my throat—I lost my voice and just pushed through it.

ALEXIS DANZIG: I was in a line of people who were carrying their beloved persons' ashes in a variety of different kinds of vessels.

TRACIE: Mm-hmm.

ALEXIS DANZIG: Some had ashes in a baggie.

TRACIE: What was your ashes in?

ALEXIS DANZIG: I had created a box. It was painted black with gold line drawings on it.

DAVID ROBINSON: And then for, like, the last section of the march, as we were getting closer to the White House, I just remember almost a grim feeling.

TRACIE: And as the White House came into view, they could see ...

SHANE BUTLER: A line of mounted police.

DAVID ROBINSON: The police had prepared by showing up with—on their horses.

SHANE BUTLER: 20 feet away from the White House gate, surrounding the entire perimeter of the White House.

TRACIE: When you look at videos of this, it's terrifying. There's these cops, like, high up on their horses, and it looks like the horses are gonna stampede them or something.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!]

TRACIE: But the protesters had a strategy.

SHANE BUTLER: The Romans called it "The cuneus." The wedge.

TRACIE: They formed a triangle with a couple people up in front pointing directly at the mounted police. And behind them are all the people carrying the ashes.

SHANE BUTLER: All you gotta do is get the front of the triangle through the straight line of the enemy, and they begin to turn around to see what's happening.

TRACIE: The protesters got the tip of that triangle between two of the mounted police and pushed through.

SHANE BUTLER: And that gave everyone else an opening to get through.

DAVID ROBINSON: The line of us, the people of us who had ashes, could get right up to the fence.

ALEXIS DANZIG: You know, all of a sudden, I remember being at the fence.

SHANE BUTLER: Physically crammed into one another as we all tried to get as close as possible.

ALEXIS DANZIG: Things became very quick and very slow all at the same time.

SHANE BUTLER: The people with the urns began to hurl those ashes onto the lawn.

DAVID ROBINSON: I remember opening this box and reaching in, and the feel of the bag and turning it over and shaking it.

ALEXIS DANZIG: I shook the box out.

DAVID ROBINSON: And feeling—seeing these ashes.

ALEXIS DANZIG: This wave of ash in the air.

DAVID ROBINSON: Some of them just falling and some going on the wind.

SHANE BUTLER: Wafted back over us and began to coat us.

DAVID ROBINSON: Then some getting on my arm.

SHANE BUTLER: The feel of those ashes, even the taste of them on your face and lips. I can remember having to clean my glasses because I couldn't see.

DAVID ROBINSON: And it was somewhere in the process of this that I went from that grim feeling to just this just fierce—I don't know, feeling like an embodiment of enraged grief.

ALEXIS DANZIG: [sighs] This incredible release of energy out into the universe.

LULU: Wow! God, I had never heard about this.

TRACIE: Yeah.

LULU: I didn't know this happened.

TRACIE: Yeah. I think when I first heard this, I think the dominant thing that I was, like, feeling and thinking was, that's so metal! [laughs]. Like, it's so—like, I just—I can't think of a, like, more pure response to that sort of anger and that disgrace.

LULU: Yeah.

TRACIE: But at the same time, you know, it just didn't—there wasn't any meaningful response from the White House. It didn't get a lot of media attention at the time. And I think if you weren't in DC that day at that moment, you probably wouldn't have known that it happened.

LULU: Man. It's like, how loud do you have to ...

TRACIE: Like, what does it take?

LULU: Yeah.

TRACIE: And honestly, that's the thing about ACT UP, the group that David was part of that made the ashes action happen, because when you look at all the other things that ACT UP did, they're just constantly trying to punch through and get people to see them. Like, for example, they did this die-in at St. Patrick's Cathedral.

LULU: What did that look like?

TRACIE: Um ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: This is Jesus Christ. I'm in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral on Sunday. We're here reporting on a ...]

TRACIE: Some of the people I had talked to, they said that the plan was go into St. Patrick's Cathedral, just lie down like they were dying or dead. You know, simple, quiet.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: You're murdering us!]

TRACIE: But some of the protesters went off script.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: Stop killing us! Stop killing us! We're not gonna ...]

TRACIE: Someone smashed the communion wafers.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: You're killing us! Stop it! Stop it!]

TRACIE: Someone else started heckling the priest.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: Stop it!]

TRACIE: And unlike the ashes action, this one got a lot of attention—but not good attention.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: When people from ACT UP started standing on pews and screaming, it really alienated the people who were praying. I saw people get very angry and upset.]

TRACIE: You know, when I learned this, I couldn't not think about our current moment. You know, coronavirus is happening.

LULU: Yeah.

TRACIE: And then the protests over the summer started to happen. There's this expression of the grief and anger that people were carrying with them. There were all these conversations about what is the right way to protest. Can a protest actually hurt the movement that you're protesting for?

LULU: Like, by being too just extreme? Or ...

TRACIE: Yeah. Or, like, too in your face or, you know—I just was wondering. And I know I'm not really supposed to wonder this because I'm a journalist. And, you know, journalists are just supposed to cover these sorts of things. But, you know, I feel like any citizen or activist or anybody has this question in their heart which is like: what would work? What would make—you know, how do you make change?

LULU: Hmm.

TRACIE: And the amazing thing about the early AIDS movement is that there were so many different kinds of protests going on that it's just like this perfect little Petri dish for this question.

LULU: What do you mean?

TRACIE: Well okay, so just to get started, let's go back to that very same day that the ACT UP activists were doing the ashes demonstration.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] Shame, shame, shame, shame, shame, shame, shame!]

TRACIE: Because right next to where they were marching on the Mall, there was another AIDS demonstration: unfurling the AIDS Quilt.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Gary Barnhill.]

LULU: I've heard of that one.

TRACIE: Yes. Yes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: David Calgaro.]

TRACIE: They did these showings of the quilt, you know, every few years.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Debbie Campbell, James Martin Case.]

TRACIE: That day in 1992, there were ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Paul Castro.]

TRACIE: ... 20,000 of these three-by-six-foot sections of quilt ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Bill Cathcart, Bob Greenwood.]

TRACIE: ... that had Barbie dolls and leather jackets and soccer trophies.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Douglas Lowery.]

TRACIE: All these mementos of people that had died.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Felix Velarde-Munoz.]

TRACIE: There were no speeches or anything like that, just ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Nicasio Trevenio Borjas.]

TRACIE: ... people reading names.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Mark S. Bowles.]

TRACIE: Each person with their own patch of quilt ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Billy Allen, Dan Allen, Clayton Barry.]

TRACIE: ... made by family members or loved ones.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Raymond Case, Dave Castro.]

MIKE SMITH: You know, you think of your grandmother taking care of you when you're sick. You think of chicken soup and tucked in bed.

TRACIE: So I ended up talking to Mike Smith.

MIKE SMITH: My name is Mike Smith. I'm the co-founder of the AIDS Quilt.

TRACIE: He was there from the beginning. And he told me that when the quilt first started, it also came from an angry place.

MIKE SMITH: If you back up to its inception, many of the earliest panels were made out of anger and desperation. Probably the best known of the angry ones is literally white vinyl with red oil paint. And the red kind of ran down in drips. Along the bottom, it says, "Ronald Reagan, his blood is on your hands." But then about four weeks before the display, we'd had some coverage in the New Yorker and a few other ...

TRACIE: Mike says right before the display in 1987, they had been putting out newsletters and doing all kinds of press.

MIKE SMITH: We'd said if you get us a panel by Octo—by September 15, we would get it into the event on the Mall a month later. And on the three days around September 15, we had 800 pieces of overnight mail.

TRACIE: Oh, wow!

MIKE SMITH: From every state. And they weren't from the gay men in the urban cores. They were from mothers.

TRACIE: It was all these, like, Midwestern ladies whose sons died of AIDS, and they had no one to talk about it with.

LULU: Oh, man!

TRACIE: They couldn't really talk about it maybe with their families.

MIKE SMITH: They couldn't even tell their church group what their son had died of. First of all, how much—how isolated and desolate do you have to be to create a beautiful, loving fabric memorial for your son, and then box it up and send it to a bunch of gay men you don't know 3,000 miles away? But we tapped into this nationwide sense of grief.

TRACIE: And that's when the panels he was seeing started to get really, really beautiful.

MIKE SMITH: Bomber jackets and high school track medals and things that Mom put on, [laughs] that really tell the story of the person. And it changed everything. By the time we got the quilt out there on the Mall, this wasn't a protest banner. It was literally all of America saying, "Wake up, our sons are dying."

TRACIE: You know, when it came to—talk about media attention, there was, like, a ton of media attention on the AIDS Quilt.

[NEWS CLIP: Good morning. It's sunrise here in Washington, DC. I'm at the Capitol Mall, where the NAMES Project AIDS Quilt is to be unveiled.]

[NEWS CLIP: A quilt. A dark reminder of AIDS and its victims was unfurled, each panel representing a death.]

MIKE SMITH: And it cracked open some political movement. I bet two-thirds of the members of Congress at some point had a mother standing in their office with a quilt panel. And then within a few years, the Ryan White Act provided $2 billion to sustain public health systems and hospitals across the country that were buckling from the weight of all of these dying people. And the fact that we could do it in a way that was also colorful and loving and warm and spoke to Middle America made us a little bit of a Trojan horse.

TRACIE: But not everyone agreed with that approach.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bob Rafksy: Angry funeral, not a sad one. The quilt makes our dying look beautiful, but it's not beautiful. It's ugly, and we have to fight for our lives.]

TRACIE: And, you know, one thing that ACT UP members were reacting to at the time was that a lot of the funerals of people who died of AIDS, they were being covered in, like, the arts section of a lot of major newspapers. And as one person told me, it was sort of like the world was seeing their deaths as aesthetic events and not as political events.

LULU: Huh.

TRACIE: Like, instead of their deaths being treated as news and politics, it was just a cultural event or something. And David in particular felt like that was what was happening with the quilt.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Robinson: I think the quilt itself does good stuff, and it's moving. Still, it's like making something beautiful out of the epidemic.]

DAVID ROBINSON: Once I saw that the people who organized the quilt and the quilt showings would allow anyone to read names—including President Bush—it was just so clear to me that we needed to demonstrate what the actual result of AIDS was. There was nothing beautiful about it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Robinson: This is what I'm left with. I've got a box full of ashes and bone chips. You know, there's no beauty in that.]

DAVID ROBINSON: I know I was adamant that I didn't want this to be symbolic. The power in what we were doing was the utterly unvarnished truth.

TRACIE: And I guess, you know, when I think about these two approaches, maybe it's sort of a false choice and you need both or whatever, but it feels like a dilemma. I'm—I know that I feel pulled towards the raw truth and expression of anger in the ashes action.

LULU: Yeah.

TRACIE: But I can also see the beauty of the quilt, and the pragmatic political power it had.

LULU: Mm-hmm.

TRACIE: And in the midst of our current moments of pain and protest, I think that's a real question, especially for the people in pain. Like, where do you put your energy?

LULU: Yeah.

TRACIE: But what I found—and we'll get right into this after the break—is a couple of moments in this movement that just totally unraveled that question.

LULU: All right. More in just a moment.

[LISTENER: Hi. This is Floria. I'm calling from Linz in Austria. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org]

[JAD: Science reporting on Radiolab is supported in part by Science Sandbox, a Simons Foundation initiative dedicated to engaging everyone with the process of science.]

LULU: This is Radiolab. I'm Lulu Miller, and we are back with our story about protests from Tracie Hunte.

TRACIE: Okay, so I'm starting a whole new story now.

LULU: Okay.

TRACIE: And this is getting at, like, if you're trying to push a government or the world to pay attention and make change, how do you do that? How do you do that while also being true to yourself, your experience, your emotions, your ideals?

LULU: Right.

TRACIE: So I was looking for parallels for what we're going through now, and a familiar name popped up.

TRACIE: Hello. Good morning. Sorry. [laughs]

ANTHONY FAUCI: Good morning.

TRACIE: A Dr. Anthony Fauci.

TRACIE: I wasn't expecting you to pick up, like, immediately.

LULU: The Fauch!

TRACIE: The Fauch.

LULU: The Fauch is in this story?

ANTHONY FAUCI: Well, I'm here. If you want me to go away, I'll leave.

TRACIE: No, no, do not. Please don't go away.

TRACIE: The Fauch is actually a big part of this story.

ANTHONY FAUCI: Well, I mean, yeah.

TRACIE: Back in the '80s, early in the AIDS crisis, he had the exact same job that he has now.

LULU: Like, truly the same title?

TRACIE: The exact same title, job, everything.

LULU: Wow!

TRACIE: The head of NIAID. And back then, he was studying immunology, the molecular architecture of fevers. Then he heard about this weird disease ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: HIV/AIDS before we knew it was HIV.

TRACIE: ... that in the United States at the time, was afflicting mostly white, young, gay men.

ANTHONY FAUCI: You know, who would have thought back in the '80s, that you would have 78 million infections and 37 million deaths from a disease that no one wanted to pay attention to?

TRACIE: His mentors at the time were like, "What are you doing? You're on this path to, like, success. Why do you want to work with AIDS patients?"

ANTHONY FAUCI: But I had a great deal of empathy for these gay young men.

TRACIE: So he ignored his mentors.

ANTHONY FAUCI: Yeah.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Now let's go to the lecture and join Dr. Anthony Fauci as he talks about AIDS.]

TRACIE: And he turned his career to focus almost completely on AIDS research.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Anthony Fauci: I'm working directly on AIDS, both clinically and from a basic science standpoint.]

ANTHONY FAUCI: It was a transforming time in my life.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Anthony Fauci: That's the amount of effort and energy that's being put into it by biomedical science.]

ANTHONY FAUCI: As a scientist and as a physician taking care of these patients.

TRACIE: And under his guidance, the NIH started to make huge leaps and bounds in AIDS research.

[NEWS CLIP: Dr. Anthony Fauci is hopeful that the answer to this dreaded disease may be in sight.]

TRACIE: You know, you hear that story, and you're like, wow, Fauci, great man. A great man then, a great man now. So brave. Wow.

LULU: Okay.

TRACIE: AIDS activists at the time ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Garance Franke-Ruta: NIH research: stupidity, incompetence and ...]

TRACIE: ... didn't fuck with Fauci like that.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Garance Franke-Ruta: Dr. Anthony Fauci is deciding the research ...]

TRACIE: Can I read you a little of Larry Kramer's open letter to you? Because it's so mean, so I feel like I have to ask permission first. [laughs]

ANTHONY FAUCI: No, no, no. Of course. I mean, that was the famous San Francisco Examiner open letter to an incompetent idiot, murderer. Right.

TRACIE: Right. Yeah. It's like, "Anthony Fauci, you are a murderer. Your refusal to hear the screams of AIDS activists early in the crisis resulted in the deaths of thousands of queers. With 270,000 dead from AIDS and millions more infected with HIV, you should not be honored at a dinner, you should be put before a firing squad."

ANTHONY FAUCI: Right. That—that, I would say, he was trying to gain my attention. And he certainly accomplished his goal. He got my attention.

LULU: Wow!

TRACIE: Yeah. So that letter was published in 1988.

LULU: Wait. But okay, so before we go on with Fauci, like, and so was he doing—like, he made this move to go work on it, but then was he somehow doing something ...

TRACIE: Something wrong?

LULU: ... dangerous? Yeah.

PETER STALEY: Well, there were—there were a bunch of issues.

TRACIE: This is Peter Staley.

PETER STALEY: Long-term AIDS activist and LGBTQ rights activist.

TRACIE: He was a big-time member of the ACT UP community. And he says that sure, yes, Dr. Fauci was doing a lot of work on AIDS. But ...

PETER STALEY: He was head of NIAID, and they were the primary institute at NIH that handled the bulk of AIDS research back then. So in essence, he was the head of AIDS research for the US government. And we had problems with that effort.

TRACIE: Back in the '80s, the drug trials that they were running ...

PETER STALEY: They had a pretty disgraceful track record of not enrolling the full diversity of patients.

TRACIE: ... tended to be really white and really male, even though the numbers of infected women and African Americans was increasing. And so, like, we're getting drugs that we don't even know if they work on anyone who's not a gay white man. And the board was also making all these decisions without the input of people who actually were living with AIDS. You know, the board was just these doctors and researchers who were playing it ...

PETER STALEY: Kind of safe, frankly. You know, we had AZT. We had the first drug.

TRACIE: But AZT was toxic. It had all these terrible side effects. And Peter Staley and others thought that there were lots of other drugs out there that could be even more useful.

PETER STALEY: And we wanted a robust research effort on those drugs.

TRACIE: But Fauci and his team ...

PETER STALEY: They just started testing the wazoo out of AZT.

TRACIE: And the few times when they did have a new drug, it took years and years for it to make it to anybody with AIDS who could actually benefit from it. And activists were like, "People are dying now. He's not moving fast enough on the things we want." So they put together a list of demands, and they set their sights on Fauci. It's time to storm the NIH.

LULU: Okay. In ACT UP land, that can't be as simple as showing up.

TRACIE: No.

PETER STALEY: On a beautiful, crisp morning ...

TRACIE: ... in Bethesda, Maryland, onto the serene campus of the NIH, all these people ...

PETER STALEY: Over a thousand demonstrators from all around the country ...

TRACIE: ... showed up and started marching.

PETER STALEY: The cops were all ready. Cops on horseback. They were quite prepared.

TRACIE: There were also TV cameras and reporters. And Peter knew that if we put on a really big, fancy display, that gives the media ...

PETER STALEY: A really colorful picture. You increased your odds of appearing on the front page.

TRACIE: And he had these colored smoke bombs ...

PETER STALEY: Surplus military smoke grenades.

TRACIE: ... hidden behind protest signs.

PETER STALEY: On the top of really long bamboo poles.

TRACIE: So they marched along with others. But then at the right moment, all at the same time ...

PETER STALEY: We dropped our poles, ripped off the signs, pulled the pins on these things, and then raised the poles back up. And these plumages of huge, thick, red, orange, blue, purple ...

TRACIE: And pinks and greens ...

PETER STALEY: ... started pouring out of the top of these poles.

TRACIE: And beneath this massive rainbow war cloud, they charged ...

PETER STALEY: ...Through the crowd. And the crowd erupted!

TRACIE: And then it was just an entire day of well-orchestrated chaos.

[NEWS CLIP: This was a major day of protest by AIDS activists in this country. One thousand ...]

TRACIE: I mean, everywhere you looked, something was happening.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phyllis Sharpe: My name is Phyllis Sharpe. I was diagnosed ...]

TRACIE: People were giving speeches.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phyllis Sharpe: The only medication that's offered is AZT.]

TRACIE: Black women talking about their experiences living with AIDS.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Scientific institution!]

TRACIE: There were people dressed up in lab coats ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: You don't fit our profile!]

TRACIE: ... making fun of scientists.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [singing] When the gays scream ...]

TRACIE: There was singing ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] Women die six times faster!]

TRACIE: ... die-ins. One section of the lawn was transformed into a graveyard. Air horns punctured the noise of the crowd.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: Basically what we're doing is blasting the horns every 12 minutes to remind people that statistically right now, every 12 minutes someone in America is dying from AIDS.]

TRACIE: And at the center of all this noise and color stood four people dressed in hooded black robes. And they carried a black coffin that had the words "Fuck you, Fauci" written on its side. They also had a really giant Fauci head impaled on a spike, and there was blood coming out of his ears, nose and mouth and his eyes. And then they burned him in effigy.

LULU: They burned him in effigy?

TRACIE: Yes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] No more secret trials!]

TRACIE: ACT UP was publicly ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] Run trials for women!]

TRACIE: ... taking that list of demands ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] NIH scientists need to work with activists!]

TRACIE: ... shaking it in Fauci's face ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] You test mice while women die!]

TRACIE: ... and nailing it to his door.

LULU: Whoa, that is intense!

TRACIE: Yeah. And Fauci is sitting up in his office, several floors up ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: Right.

TRACIE: ... looking out the window.

ANTHONY FAUCI: They were really confronting me in a very, very aggressive way.

TRACIE: And as he was taking it all in ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: I saw him from my window.

TRACIE: ... amidst all this chaos, the slight figure of Peter Staley getting boosted up onto this ledge above the front door of the building.

PETER STALEY: Yeah, I got on the overhang ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: You could see that he was on this little overhang.

PETER STALEY: ... and started hanging up banners. And the crowd cheered. But the cops were having none of it that day.

ANTHONY FAUCI: And the police were gonna climb up and get him.

PETER STALEY: They launched a few of their own up onto the overhang and tackled me.

TRACIE: The police are, like, scrambling.

PETER STALEY: Lowered me down in the hands of a dozen cops.

TRACIE: And they had to take him to the police van. And the police van is, like, in the back of the building. And because the building is now surrounded by activists, the only way to get him to the back of the building is to take him through the building.

PETER STALEY: So they handcuffed me behind my back, and an officer grabbed my elbow and started hauling me through the first floor of Building 31. And as we're going down this wide corridor, I see that familiar white lab coat on that short scientist coming towards me. [laughs]

ANTHONY FAUCI: He had handcuffs behind his back, and this police officer was taking him away. And he passed me, and he said ...

PETER STALEY: "Tony?" And he goes, "Peter?" And Tony said, "Are you all right?" I said, "Yeah, yeah. Just doing my job. How about you?" And he said, "Well, we're trying to keep operating under these conditions." And I said, "Well, good luck with that. We'll talk tomorrow."

ANTHONY FAUCI: And I said, "Okay, Peter. See you later." And the cop looked at me like, what the hell is going on here?

LULU: Wait. They know each other?

TRACIE: Yeah. And this is the first little piece of the puzzle in explaining why this action was so different from the ashes action or even the Quilt. And to show you what I mean by that, we have to go back two years to 1988, to that letter that Larry Kramer wrote to Fauci where he called him a murderer.

TRACIE: Do you remember that?

ANTHONY FAUCI: Yeah.

TRACIE: The whole murderer thing?

ANTHONY FAUCI: Of course. Of course.

TRACIE: When Dr. Fauci saw that letter, he thought ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: If somebody is that angry to be able to print that in a national newspaper, I mean, I gotta find out what is it that has stimulated him to do that?

TRACIE: So he just called this guy who called him a murderer, called him on the phone and said, "Let's figure this out." And despite their differences ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: We—you know, we came to an agreement that we both had the same common goal.

TRACIE: Yeah. Well, I'm—I'm really surprised by that because, like, you know, I'm thinking of, like, the Storm the NIH protest, when people literally have, like, pictures of your head on a ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: Yep.

TRACIE: ... of your head on a stake and saying, you know, "Eff you, Fauci!"

ANTHONY FAUCI: Well, no one was really able to listen to their message because they were too put off by the tactics. And I think the thing that I was able to do was to separate the attacks on me as a symbolic representative of the federal government that they felt was ignoring their needs.

JAD: Dr. Fauci, I wonder if I can follow up on that.

TRACIE: That's our host, Jad Abumrad. He was sitting in on the interview with Fauci.

JAD: It's kind of an extraordinary emotional jiu jitsu that you're describing. I mean, to—people are saying horrible things, which ...

ANTHONY FAUCI: Right.

JAD: ... could be read as symbolically about a person in a role, or could be taken quite personally. And you're saying everybody around you is taking it quite personally, but you somehow were able to shift posture.

ANTHONY FAUCI: Right. Right.

JAD: Do you have any recollection of how you did it? Like, what specifically got you out of defense and into receptive mode?

ANTHONY FAUCI: You know, I think it's a complicated thing. My—it really dates back to my family. My mother and father were very much people who were quite tolerant of different opinions. And part of not only my background but the Jesuit training both in high school and in college, is that you care about people no matter who they are, and you keep an open mind to opinions.

JAD: Huh.

ANTHONY FAUCI: Once you become defensive and push back, you never hear what their message is. And once you listened to what their concern was, I got this feeling that, goodness, they're right.

LULU: Wow. It is so hard to picture a person in power responding like that today.

TRACIE: Mm-hmm.

LULU: You know, it seems like when someone spits on your face and says awful things about you, the main move you see is people screaming back louder or, like, blocking you on social media, not acknowledging or hating back.

TRACIE: Yeah. I mean, there's a part of me, like, when I hear this story where I'm just like, you know, that's like a really easy way to make himself look good. But at the same time, you know, even me who's like Ms. Cynical, can't deny the fact that that was, like, a pretty cool move on Fauci's part to turn that moment into a moment for, like, a conversation. And after that initial phone call, Larry Kramer actually connected Dr. Fauci with Peter Staley and a couple of other activists.

PETER STALEY: Fauci swung his office door open.

ANTHONY FAUCI: I said it's time for me to put the theatrics aside and listen to what they're saying.

PETER STALEY: And we had a very healthy back and forth.

TRACIE: And you know, a little while after that, those phone calls turned into dinner parties.

PETER STALEY: These famous dinners we would have with him in Washington.

ANTHONY FAUCI: Sitting down around the dinner table of my deputy at the time, Jim Hill.

TRACIE: They'd discuss ideas, strategy, medicine.

ANTHONY FAUCI: How we can continue the dialogue of coming to some common ground.

TRACIE: And now this is all still before Peter and others stormed the NIH. And this is actually where Peter would bring up the list of ACT UP demands. Like, "Hey, Dr. Fauci, could you please pass the salt? And also, we think that you really need to diversify your trials." "Hey, Dr. Fauci, this pie is so good. What'd you put in it? But you know what's not good? AZT. Let's start testing more drugs." And Fauci ...

PETER STALEY: Well, you know, he kind of passed the buck.

ANTHONY FAUCI: I mean, I had a lot of pushback from my own colleagues in the scientific community.

TRACIE: ... he just had a lot of excuses.

PETER STALEY: We were sick of hearing from him tell us for over a year ...

TRACIE: Dinner after dinner after dinner ...

PETER STALEY: ... I understand you. I agree with you, but I can't convince the executive committee. And we were like, screw that.

TRACIE: Peter and others were like, you know what? Empathy and listening and dinners, it's not enough. So it was actually at one of these dinners Peter told Dr. Fauci ...

PETER STALEY: I said, "Tony, I got bad news for you. In a couple of months, we're gonna descend on your campus with a massive demonstration to push these issues."

TRACIE: And what did you say?

ANTHONY FAUCI: I said, "Wait a minute. [laughs] We're sitting—we're sitting here having dinner and sharing a glass of Pinot Grigio, and you're gonna storm the NIH? What are you talking about?"

PETER STALEY: He tried to talk us out of it.

ANTHONY FAUCI: No, I did. You know, I said, "Peter, are you sure that this is gonna be a productive thing?"

PETER STALEY: Kept pleading that he needed a little more time. And we said, "Well, you got a couple of months."

ANTHONY FAUCI: I said, "Oh, okay. Fine. Thanks an awful lot."

TRACIE: Couple months later ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] The whole world is watching!]

TRACIE: ... a thousand people show up to his door with his head on a spike.

LULU: Yeah. Well, what happened? What did happen? Was it tons of—did the media pick it up?

TRACIE: There was a lot of media attention. And thanks to Peter's colored smoke bombs, it actually did make the front page of a couple of newspapers. But a lot of the media attention was not sympathetic. It was just like, look at these ...

LULU: It was not sympathetic. Oh.

TRACIE: It was not—look at these crazies who showed up at the NIH.

LULU: Okay.

TRACIE: But the thing that makes this protest different from the ashes action or even the Quilt is that they were saying fuck you to somebody who was actually sympathetic to them.

PETER STALEY: That demonstration was more about putting him between a rock and a hard place. We were the rock, and the hard place was the executive committee of the ACTG.

TRACIE: This was about giving Fauci a very public boot in the ass.

PETER STALEY: We wanted to make it politically difficult for them to ignore him and us. And so he got squeezed by ACT UP.

TRACIE: And that squeeze was apparently exactly what he needed because ...

PETER STALEY: He did kind of what we were hoping he'd do. He pushed the ACTG harder. And within a few months of that demonstration, the ACTG executive committee caved.

TRACIE: They got pretty much everything they wanted.

LULU: Like, on that list, they got it all?

TRACIE: Yeah.

PETER STALEY: The ACTG decided to open up all of their committees.

TRACIE: Activists and other people with AIDS were added to the panels.

PETER STALEY: We got voting membership on the executive committee.

TRACIE: They did diversify the people that they were testing. They did begin to start testing drugs that weren't AZT.

PETER STALEY: And we started to reformat and refocus the clinical trials, and the conducting of clinical trials towards HIV/AIDS.

TRACIE: They got—they got what they needed.

LULU: Wow!

TRACIE: Yeah.

LULU: That is so not a story I feel like you ever hear.

TRACIE: Yeah. But to be clear, the Storm the NIH action happened in 1990. It wasn't until 1996 that they actually had the drug cocktail that was giving people living with AIDS a much longer life. And so it was actually after the Storm the NIH action that Larry Kramer was giving these angry speeches about how desperate the situation was. And David and Alexis throwing their loved one's ashes on the White House lawn? That happened after Storm the NIH. And, you know, you can certainly point to the ashes action and other political funerals that ACT UP did during that time period as, like, you know, not being as effective as Storm the NIH, but when the situation is so dire and things are so dark and people are so desperate, maybe that moment called for a different kind of demonstration.

ALEXANDRA JUHASZ: That is exactly right. And this is me as a media scholar talking and a rather radical one.

TRACIE: This is Alexandra Juhasz. She is a professor of film at Brooklyn College, and she worked in ACT UP.

ALEXANDRA JUHASZ: I don't know that—you're a media maker.

TRACIE: Mm-hmm.

ALEXANDRA JUHASZ: One goal is to quote-unquote, "Change someone's mind."

TRACIE: Yeah.

ALEXANDRA JUHASZ: Okay. That's a real goal. And you make certain kind of work to, quote-unquote, "Change somebody's mind." There was an organization at this time that I knew called AIDS Films, and they made a number of short, narrative, highly polished films. And those were definitely change-mind kind of films 'cause they were feel-good, they looked familiar. Now that's a reasonable goal. But I'm not sure that Stop the Church or the ashes action or political funerals, the goal is to change someone's mind. The goal is to express your anger. The goal is to express your desperation. The goal is to say no. The goal is to say this is wrong.

TRACIE: Mm-hmm.

ALEXANDRA JUHASZ: Those actions by ACT UP were to express defiance, and to put defiance on the map.

TRACIE: You know, she was like, protest is about, like, making sure that this thing is never gonna go away. And I kind of had, like, a moment like that because I was talking on the phone with a friend, and all of a sudden, I was—I heard outside my window "Say his name! George Floyd!" And part of me was like, "Again?"

LULU: Really? Did you really think that?

TRACIE: For a second, yes. I should say that where I live, like, there were protests almost every day during the summer. And so I had actually gone a few months without hearing any. And then it was happening outside my window, and I did have that reaction. And then I was like, "Wait. What am I annoyed with? What am I really annoyed with?" And I realized, like, what I'm really annoyed with is the fact that another Black man was killed in Philadelphia, and that's why the protest was happening again. And I also realized that, you know, it was a reminder, you know? We're not done.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protesters: [chanting] Bringing the dead to your door! We won't take it anymore! Bringing the dead to your door ...]

TRACIE: And David and Alexis, and all the other people involved in ACT UP, every week, it was like another action, and it was another funeral. And then there was, like, another action. It kept going and going and going. And there hadn't been really any moment to, like, just stop and assess all the trauma they'd gone through. But after they made it through the mounted police to the fence, and …

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: I love you, Mike!]

TRACIE: ... let go of those ashes ...

ALEXIS DANZIG: This incredible release of energy out into the universe.

TRACIE: ... they say there was this moment.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: The magnitude of what had just happened hit me. I just began to sob convulsively.]

DAVID ROBINSON: One of ACT UP's slogans had been, you know, turn your grief into rage. Larry Kramer was very fond of saying that. But to really experience our grief? Oh, wow! Like, if Warren—I hundred percent knew then and know now he would have approved and, you know, been proud.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: This was my friend Kevin Michael Kick. He was 28 years old, and he died on Halloween, 1991.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: The main reason I'm here is to scatter my own ashes. I'm going to die of AIDS in probably two years, and that is why I'm here.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Alexis Danzig: I'm here on behalf of my father, Alan Danzig, who died when he was 57 years old. I really needed this.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Eric Sawyer: My name is Eric Sawyer, and I've scattered the ashes of Larry Kert. Larry Kert was 60 years old. He was the original Tony in West Side Story on Broadway in 1957. Larry was to have his last professional performance at the White House. He was invited to a party to sing with Carol Lawrence. They were gonna sing "Somewhere (There's A Place For Us)," and he planned to come out as a person with AIDS. And when the White House administration found out he was going to do that, they conveniently lost his music just before he was to go on.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, activist: I came to scatter the ashes of my lover, Michael Tad Hippler. Truth to tell, I had scattered all of his ashes that I had, but I was sitting at breakfast with his sister, and I told her about this demonstration. And her eyes lit up, and she said, "Hey, do you want some ashes?" So I love you, Mike, and I know you would have wanted to be where you now are.]

LULU: Reporter Tracie Hunte. This episode was produced by Tobin Low and Annie McEwen. Special thanks to Elsa Honesun, Joy Episalla, Debra Levine, Theodore Kerr, Ben McLaughlin, Catherine Gund at DIVA TV for the use of the NIH protest footage, Diane Kelly for fact-checking and James Wencey for archival footage, Christine Pfahl for archival research and Diane Kelly for fact-checking.

LULU: And before we go, we have to share that Tracie has just wrapped up her time with us. In the short bit of time I got to be here working with her completely changed how I see reporting and teamwork. I'm going to miss her so much, and I know Jad wants to say something.

JAD: This story, unfortunately for us, is Tracie's last story with Radiolab. She has been with the show for about four years. You've heard her in stories from Soraya to square dancing to the Nina Simone story this summer, and she's left quite a mark on all of us. And we're so proud to have worked with you, Tracie. Tracie's moving really just down the hall from us—it's a virtual hall for the time being, but soon-to-be actual hall, we all hope—to work on the new collaboration with The Atlantic, the WNYC-Atlantic collaboration that's being hosted by "More Perfect" alum Julia Longoria. So we're happy that she'll be close by, still kind of in the family. And we're gonna keep trying our best to create excuses for her to come make radio with us. We love you, Tracie, and we wish you the best.

[LISTENER: Hi. This is Anand Krishnamoorthi from Pasadena, Calif. Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is edited by Soren Wheeler. Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are co-hosts. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Suzie Lechtenberg is our executive producer. Our staff includes Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, Becca Bressler, Rachael Cusick, David Gebel, Matt Kielty, Tobin Low, Annie McEwen, Sarah Qari, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster. With help from Shima Oliaee, Sarah Sandbach and Johnny Moens. Our fact-checker is Michelle Harris.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.