Jun 7, 2018

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Jad here. So next week, we're gonna launch a new miniseries here on Radiolab from Molly Webster. Molly is somebody who, if you've listened to the show for a while, like, you know her voice, you know her vibe. She's been reporting mostly science stories here at Radiolab for about five years. She's begun to host the show on occasion. And next week she's gonna start up a month-long series about the seemingly ordinary, but in truth utterly bizarre and magical and deeply weird and ethically fraught business of humans making more of themselves.

JAD: Now this is a beat that evolved over time for her. And I thought as a prelude to Molly Town, let's play one of the big foundational stories that got her—and all of us—thinking about this whole world. I'm not sure that we've ever spent so much time and energy and money, frankly, reporting a story as the one you're about to hear. Those of you who have heard this, check back in with us in a week. For those of you who haven't, I think this is actually one of the best things we've ever made. In any case, here it is. And next week, it's on!

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Webs?

MOLLY: Oh, am I allowed to talk?

JAD: Yeah, do it.

MOLLY: Oh, I'm Molly Webster

ROBERT: Yeah, you just graduated.

JAD: Join the party, Molly. Join the party. And today we have a—I don't know, we have a birth story.

ROBERT: We're calling this "Birthstory" because that's what it is. They—we're gonna tell you about babies, who were very recently born, and who one day, will turn to their parents and say to them, "Tell me how I got here. Like—like, what's—what's ..."

JAD: "What's my story?"

ROBERT: "What's my story?" And the parents, in this case, will say, "Well ... "

JAD: "That's complicated." [laughs]

ROBERT: [laughs] That's—yeah. This is one where the kids will hear what you're about to hear and they'll go, "Really?"

JAD: It's a collaboration with a—a team of reporters in Israel called Israel Story. They are a group of folks who do sort of long form reporting and storytelling. They've been doing it in Hebrew for three years, and they are in the middle of their first English language season right now. And ...

ROBERT: Which we're gonna be in.

JAD: Exactly. And this is two producers that we worked with in particular, Maya Kosover and Yochai Maital. And this story begins with Maya.

MAYA KOSOVER: Okay, it was a party, and we were all dancing Israeli music in the middle of Jaffa.

JAD: It was her birthday. They were at her apartment. And this guy Tal ...

MAYA KOSOVER: Tal was dancing with his partner.

JAD: These are friends of yours?

MAYA KOSOVER: Yeah. Tal is kind of a megastar in the deaf community in Israel 'cause he translates the news in the TV to deaf people, to sign language.

JAD: Oh wow, so he's like the little guy in the corner of the TV.

MAYA KOSOVER: Yeah.

JAD: And his partner?

MAYA KOSOVER: Amir.

JAD: Amir, or Amile?

MAYA KOSOVER: Amir.

JAD: With an R.

MAYA KOSOVER: He's a psychologist that works specially with children that are autistic.

JAD: Anyway, they're at the party.

MAYA KOSOVER: So we were dancing all together, and then Tal was, "Oh my God, maybe it's going to be the last party that I'm in 'cause I'm going to be a parent, and not only a parent, I'm going to be a father for three." And then, we were like, "Oh my god. Three babies! How is that going to happen?"

JAD: And it turns out, how that was gonna happen is—it's a crazy story involving four countries ...

MOLLY: Three women.

ROBERT: Two guys and—and ...

JAD: Three babies, as we mentioned.

ROBERT: And planes, jet planes.

MOLLY: Two—jet planes. Two of them.

ROBERT: Hundreds of thousands of dollars.

MOLLY: At least four languages?

ROBERT: Yes. I think so, yes. All that.

JAD: But we should—we should go back a bit. To the beginning.

AMIR: The first thing that I saw in Tal is—is his ability to be a father.

JAD: This is Amir.

MOLLY: Really?

AMIR: Yeah.

MOLLY: How so?

AMIR: Because he was a good man, you know? He was very gentle and really an adult to build the family. I don't know to describe it ...

YOCHAI MAITAL: Mensch. I think in America it's also called mensch.

JAD: [laughs]

MOLLY: [laughs]

ROBERT: Okay, we know what that is.

MOLLY: And did you see that, like, on first meeting, or was this, like, four months in?

AMIR: My career is established to work with autistic people and to take notice for every sign of—of communication and—and to understand other people and to analyze them. So it was really immediate, I think.

TAL: Let's say after two or three times he say, "Okay, I want children. So are you interesting?"

AMIR: I wrote a manifesto about my future, what I want to do, what I want to do in my career, it's kind of my vision. And I gave it to him and I said, "Listen, this is what I want."

JAD: Sign at the bottom, please.

AMIR: Yeah, it kind of was a contract. It's like, this is what I want. If you want to join me ...

TAL: So let's do it.

AMIR: So let's do it.

JAD: And Tal, what's your reaction to the—to the manifesto?

TAL: I like it. It looked like someone who want a future.

ROBERT: Did you own parents have any—either of your parents have any views about that? Saying, "Don't." "Do." Or, "This is weird." [laughs]

TAL: [laughs] Yeah.

JAD: Suffice to say their families did not approve, especially when it came to the idea of them having kids. Now how to have those kids, that is a question.

YOCHAI MAITAL: Basically, there are—there are two options if you're a gay couple and you want to have—there used to be three options.

JAD: That's Yochai Maital from Israel Story, here is how he and Maya laid it out for us. Option number one, which is now not as much of an option ...

YOCHAI MAITAL: You could adopt a kid from a third world country.

JAD: But he says over the last few years what happened is that those third world countries figured out who was adopting their babies and one by one they banned it for gay couples.

MAYA KOSOVER: Yeah.

YOCHAI MAITAL: The second option, which is becoming very, very popular in Israel is sort of the new family—that's what it is called in Hebrew at least. Sort of getting together with another woman who wants to be a mother but doesn't have a—a father. And then they do a joint parenthood.

JAD: They all live in the same house?

YOCHAI MAITAL: No. The mother lives separately, and it's kind of like divorced parents that get along really well.

MAYA KOSOVER: They sign a contract before the process, and everything is like in the contract.

JAD: Tal and Amir said that early on they tried this route.

AMIR: Tal got an offer from one of his friends to do the co-parenting, but then I spoke with Tal and asked him, "Listen, it's very important for me to have a baby of my own and with my sperm."

TAL: And I said to Amir, "I want to try, but I don't care if in the end we have only one baby in your sperm, so it will be my baby the same."

AMIR: I think, I—I was more stubborn about it than Tal.

JAD: Amir couldn't really explain why it was so important to him, just that it was important to him. But reflecting on it later, Maya from Israel Story put it this way ...

MAYA KOSOVER: It's very Jewish and Israeli. I mean, if you are not in the Israeli mainstream, if you are gay or if you are different and you have your own baby, it's like a signature of being part of the game, you know?

JAD: Whatever the reasons, Amir and Tal talked it over and then they went back to this woman, Tal's friend who had offered to do the co-parenting ...

TAL: And we asked her if she can obligate to us to bring two children, one of Tal's sperms and one of my own.

JAD: In the end she said ...

TAL: No.

JAD: And at this point, a year had gone by.

TAL: So then we decided that maybe the best option will be ...

AMIR: Option three is—is ...

TAL & AMIR: Surrogacy.

JAD: Meaning, of course, if you are a gay man that you take your sperm, take some eggs from a woman, put your sperm in those eggs into the womb of a second woman who carries the baby to term.

YOCHAI MAITAL: But surrogacy is illegal in Israel.

MAYA KOSOVER: Only for gay couples, yeah.

JAD: In Israel, if you're a hetero couple, you can use an Israeli woman as a surrogate but if you're gay you can't.

YOCHAI MAITAL: So there is a big problem, but that problem also creates a big demand. As you can imagine, there are quite a lot of gay couples in Israel, and so companies sprang up basically offering international brokering of sperm, eggs and ovaries.

MAYA KOSOVER: Babies outsourcing.

JAD: You can see this play out every year at these conferences in Israel.

YOCHAI MAITAL: Conferences where they get prospective parents together.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: We are here for our first time in Tel Aviv.]

JAD: So it's this big room of people.

YOCHAI MAITAL: Several hundred people.

JAD: Pretty much all gay men.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: Pardon me for not being able to speak Hebrew very well, or at all... ]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: Shalom.]

JAD: Basically what happens at these conferences is that surrogacy agencies will get up and basically sell their products.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: We now offer surrogacy in Mexico ... ]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: Thailand.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: Panama.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: The United States.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: India.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: Anybody been to Fort Worth? Very nice place. You can go see a basketball game, you can go see a baseball game.]

JAD: These agencies will find women in all of these places who will serve as the surrogate for your child. And depending on which country you choose and whether or not you provide the donor eggs, or they do, or a million other factors, the costs will vary.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: We offer very competitive prices, for example, $36,000 complete start to finish in Mexico, $38,000 in Thailand.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: Anywhere from $65,000 to $85,000. $150,000 it could be that much. ]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, voice: That's excluding the donor of course, but we have a good selection of donors, including Jewish donors as well.]

AMIR: Yeah, you have sessions with the lawyers, you have sessions with ...

TAL: With the families, you have sessions with ...

AMIR: Families with doctors.

JAD: Tal and Amir went to two of these conferences in successive years and coming back from the second one ...

AMIR: We take a calculator and we start to think how we can make it. [laughs]

ROBERT: Raising money?

AMIR: Money, money, money. Yeah.

JAD: They figure if they go with a company that does surrogacy in the US ...

TAL: It's probably going to cost $150,000 or ...

ROBERT: Is that lawyers and ...

AMIR: Lawyers ...

TAL: Yeah.

AMIR: The hospital.

TAL: Sperm delivery, the egg donor. There is a lot of people that we need to pay.

JAD: And he says keep in mind when you pay that money, you are not guaranteed a baby.

TAL: You buy a process. We don't buy a baby.

AMIR: One of our friends did this kind of process, and they spend five times and they still didn't succeed.

ROBERT: Five times?

AMIR: Yeah.

JAD: They figured with that kind of risk, doing it in the US was just too expensive. And so they started looking at surrogacy agencies which operate in India and Nepal.

AMIR: Because over there you can do the same thing and it will cost you about $60,000.

ROBERT: So it's almost half price?

AMIR: Almost half price, yeah.

JAD: Now one of the tricky things, according to Yochai, is that in 2013 ...

YOCHAI MAITAL: India basically outlawed surrogacy.

MAYA KOSOVER: For gay couples. I mean, if you're a straight couple you can do surrogacy in India.

JAD: But not if you're gay.

YOCHAI MAITAL: Also in Nepal, by the way. Nepal also outlawed surrogacy.

JAD: Effectively, the cabinet said if you're a Nepali woman you cannot be a surrogate period.

YOCHAI MAITAL: But there's sort of a loophole: Indian women are allowed to be surrogates in Nepal, just Nepali women aren't allowed to be surrogates in Nepal.

JAD: So what ends up happening is this really strange situation.

MAYA KOSOVER: It looks like a puzzle.

JAD: These agents in northern India will find Indian women, move them across the border into Nepal, take them all the way to Kathmandu where the surrogacy agencies have set up shelter houses and work with local hospitals and clinics. Maya says for Tal and Amir the decision to do it this way was not easy.

MAYA KOSOVER: They—they had, like, different opinions.

AMIR: Tal had a bigger issue with the moral concept of this process.

MAYA KOSOVER: Amir was like, "This is the thing that we need to do. I want to be a father."

AMIR: But Tal ...

MAYA KOSOVER: Tal was—it was very hard for him.

TAL: I thought if it's—it's immoral to do things like that, to use another woman to give me a present like that and—and I know she will never—will see this baby anymore.

MOLLY: Is it immoral because you're essentially, like, just using a woman's body, or ...

TAL: Yeah. Yeah. You could say.

MAYA KOSOVER: He felt like he's using other people's bad luck for his own good.

JAD: Yeah.

MAYA KOSOVER: She has no choice, she's not doing it out of freedom, she's just doing it for the money. And maybe it's not morally okay that we'll use this weakness.

JAD: Tal and Amir went back and forth on this for months, and eventually the argument that won the day was this: that if they're gonna do it they're gonna do it with this agency called Lotus, which to their understanding paid the surrogates $12,000. I mean, the surrogates were actually paid in Indian rupees, but that would be the dollar equivalent. $12,000. Now for a rural woman in India, that is a massive sum of money. They figured this won't just help her survive, it will change her life. She'll be changing their life, and they'll be changing hers.

TAL: Maybe this was ...

AMIR: Kind of comfort.

TAL: Yeah, they get money, they can change their life. They can buy a house, they can send their—her children to school to learn in the university. When I thought and understand it will be a life changer and it's not ...

AMIR: Exploiting.

TAL: ... exploiting to her. So I agree.

JAD: At the start of the whole process ...

MAYA KOSOVER: One of the main issues was to pick the egg donor.

MOLLY: And, like, who are these women? Like, where do they come from?

TAL: Ukraine.

AMIR: They're from the Ukraine.

MOLLY: They're all Ukrainian? What—that—that is not a country I expected to be thrown into the mix of countries.

YOCHAI MAITAL: The reason the eggs are from eastern Europe are generally because ...

MAYA KOSOVER: They're white.

YOCHAI MAITAL: ... because they're white. So it's like cheap white eggs.

JAD: Cheap white eggs. [laughs] Wow, that's quite a phrase! [laughs]

AMIR: So you have like a website, and you see a lot of pictures of women.

TAL: Yeah.

AMIR: And then you need to choose the most ...

TAL: It's like Jdate.

AMIR: Yeah.

JAD: Jewish online dating service.

AMIR: Yeah. I think it was the most straighty-ish act that I did in a very long time.

JAD: Oh, straightest. I see.

MOLLY: Oh. ‘Cause you're picking out a lady.

AMIR: Yeah.

JAD: Yeah, how did you decide which criteria you wanted in a—in a donor mom?

TAL: Oh.

AMIR: The first one was height.

JAD: You wanted someone tall.

TAL: Yeah.

MOLLY: Why? Why was height your first one?

AMIR: Because ...

TAL: It's more easy to—to live when your height.

AMIR: Yeah. Yeah.

MOLLY: Okay.

AMIR: Then eyes.

MAYA KOSOVER: She has these thick eyes ...

JAD: They showed Maya a picture.

MAYA KOSOVER: Light brown hair and she has this nice nose. It was, you know, very strange.

TAL: It was very uncomfortable to choose. For me, it was very ...

YOCHAI MAITAL: Like a genetical, like improving ...

MAYA KOSOVER: Oh, you felt like you were doing like a eugenics.

TAL: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Eugenics.

ROBERT: Huh.

JAD: Now since Tal and Amir had each wanted a baby with their own sperm, they told Lotus ...

MAYA KOSOVER: We would like to rent two wombs, one of each sperm and to try to use, like, two surrogate mothers.

JAD: Lotus said, "Fine, that's gonna run you ..."

AMIR: About $50,000-$60,000 each pregnancy.

JAD: Again, no guarantees. So Tal and Amir they give Lotus their sperm in little cups, Lotus freezes the sperm, sends it to a hospital in Nepal. The Ukrainian woman, the egg donor, is flown to Nepal, her eggs are harvested. Somewhere along the way, two north Indian women are moved across the border into Nepal. Finally, that doctors at the Nepali hospital take the Israeli sperm, inject it into the Ukrainian eggs, create some embryos and they implant those embryos in the wombs of the Indian surrogates. Four countries, one baby. A few months go by, they get the news that both surrogates are pregnant. The process worked. One is pregnant with twins, three babies in all. They're sent sonograms, pictures of the surrogate's pregnant bellies.

TAL: I all the time look on the picture of her, all the ultrasound pictures, all the time looking on my cell phone in the picture.

JAD: Because Tal says there wasn't really much he could do, ‘cause for three or four or five months not much happened. Until six months in ...

AMIR: Six o'clock in the morning.

TAL: Six o'clock in the morning Diana from Lotus called us, and Amir was answered the phone. And I hear him said, "Okay. They're okay?" I wake up and say, "What?" Because, it was too ...

AMIR: ... early.

TAL: Too early.

JAD: How early?

AMIR: About eight–eight weeks ahead.

JAD: Wow.

JAD: The surrogate who was carrying twins had given birth.

TAL: I was crying a lot.

JAD: This is the surrogate carrying Tal's baby, which turned out to be two babies.

TAL: Yeah.

JAD: And were you on the plane the same day as getting that call, or ...?

TAL: Day after. We fly from Tel Aviv to Istanbul and from Istanbul to Kathmandu. It was very crazy day, and then Gil ...

JAD: This was one of Tal's friends who was also in Nepal for surrogacy.

TAL: He took me to the hospital, and well, I—I was shocked because Gilly was so tiny.

JAD: Gilly was 3.8 pounds. His brother Uval, 4.8 pounds.

TAL: And I was very scared to touch him.

JAD: He says he expected the twins to stay in the hospital for a month, but the nurses were like, "Nope, going home tomorrow."

TAL: I thought, "I don't have enough time to think because I understand tomorrow I need to take them home and to be alone," and I never take care any babies so I said—I said to the nurses, "Teach me how to feed them," and after three days I took them home.

ROBERT: So where was the surrogate during these days? Was she at the hospital?

TAL: I think she was in the hospital, yeah.

AMIR: Because she had a—a cesarean surgery.

TAL: I was ask if she's okay and if she needs something. They said, "You—you cannot see her until she signed all the papers and then you can see her."

MOLLY: So the papers hadn't been signed?

AMIR: Yeah, because we need that she's giving up all her maternal rights, and if she doesn't want to sign on this paper we can lose the baby.

JAD: The laws on this get crazily complicated, but basically they needed Israel, India and Nepal to all recognize that they were the uncontested parents. And hanging in the air ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Voice: We've been terrified... ]

JAD: ... was a recent case in Thailand, which was all over the news where the surrogate, after the baby was born, changed her mind.

[NEWS CLIP: Lake and his husband believe the surrogate decided to try and keep the baby because she found out they were gay.]

AMIR: We had a little bit of an anxiety, let's say, if they were going to know that the baby is going to grow in a house with two dads.

JAD: In any case Tal is in Nepal with the twins, Amir is back in Tel Aviv. A couple weeks go by and then ...

AMIR: Tal called me and said, "Mazel tov, you're a dad."

JAD: The second surrogate had given birth. One baby.

AMIR: And ...

TAL: Day after: Tel Aviv to Istanbul, going from Istanbul to Kathmandu.

AMIR: And then it was very, very, very, nice that we went. Only us, with the babies, with like no parents, no friends, no phone.

TAL: No phones, no world.

AMIR: To build the first blocks of our relationship with the babies.

JAD: And for the next month they lived in an apartment in Nepal, just them and their three babies, learning to be dads, and waiting for the paperwork to be done. Now the paperwork incidentally is a beast, because after the surrogates sign away their rights, the babies have no nationality and then they're suddenly illegally in the country. So then the guys have to take a DNA test, send it to Israel, get it verified. Then they've got to get a passport for the babies, then several sets of visas need to be gotten. And all of that means multiple trips to the Israeli Embassy. And it was on one of those trips that they learned something.

AMIR: It was really weird, because we went over there with our kids to get the passport, and over there there was another surrogate from a different agency.

JAD: An Indian woman. And standing next to her was an Israeli woman who happened to speak Hindi.

AMIR: And we just—you know, out of curiosity we asked her to ask the surrogate in Hindu how much is she's—she's getting.

JAD: For the whole process.

AMIR: Yeah.

TAL: But the—the surrogate was very shy.

AMIR: Yes, not very delighted to speak about the money.

JAD: Which made them even more curious so they persisted.

AMIR: And then we discovered that ...

TAL: ... she gets only $3,000 US or something like that.

YOCHAI MAITAL: $3,000 for the whole pregnancy.

JAD: Amir was like, "Wait a second."

AMIR: In the agreement $12,500 supposed to go to the surrogate.

JAD: That was at least his understanding. Now this was a different woman from a different agency, and this was just one woman's account, but still ...

ROBERT: In your narrative you've described that you thought that the reason that this was okay to do, the surrogacy, is because you are—you—the phrase you used was this will "Make a change in the life of the woman that we're paying."

AMIR: Yes, a life-changing sum of money.

JAD: So Maya says they walked away from that meeting ...

MAYA KOSOVER: Wondering if they should do something in Israel.

JAD: You know, call the agency at the very least, say, "Hey, we heard some rumors. I'm sure they're not true, but what do you think?"

AMIR: We started to ask question but then ...

JAD: Literally the next day ...

[NEWS CLIP: Horrendous scenes of death and destruction from Nepal today, after a powerful earthquake that started outside Kathmandu.]

[NEWS CLIP: The death toll is now over 5,800. Nearly 14,000 are injured.]

[NEWS CLIP: Officials say it is the most destructive earthquake to hit Nepal in more than 80 years.]

JAD: The death toll would ultimately rise to somewhere between seven and ten thousand. Maya says she was in New York in a meeting and she gets this voicemail from Tal ...

MAYA KOSOVER: And he was shouting, "An earthquake just happened here. We saved the babies and we got down to the street. We're half naked, we don't know what to do.” And he's crying over there, and then ...

MAYA KOSOVER: It suddenly stopped. He lost the connection. It was like 12 hours with no connection to them. We didn't know if they're alive or not. You know, everything was unknown.

AMIR: I don't know how, but Tal took his cell phone and we just ran barefoot ...

JAD: Amir says they ran out of the apartment down the street half naked holding the babies and the phone. On the way they ran into their friend Gil, who had four babies, another couple who had two babies.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gil: We are in this street and we are nine babies.]

JAD: They actually shot a video on Tal's phone. You see Tal only in shorts, a bunch of other couples holding babies. And they're all literally standing on a pile of rubble. As they're standing there a guy with a badge walks by.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gil: You're a policeman? Ah, hello. You're from the American Embassy? We're Israeli citizens. We have here nine babies. We need help. Please, we don't have food for the babies. Thank you.]

AMIR: So they took us in to the embassy.

ROBERT: The US Embassy, or the ...

TAL: No.

AMIR: No, the Israeli Embassy.

YOCHAI MAITAL: They went to the Israeli Embassy, and the Israeli Embassy sort of went into emergency mode.

AMIR: They gave us a—some blankets.

YOCHAI MAITAL: And they put out—put out tents.

JAD: And shortly after, the news cameras arrived. And Tal ...

YOCHAI MAITAL: Tal is—Tal is—he's like in the media and stuff because he's the–he's the sign language translator, and so he realized that he doesn't have any way of communicating back home that he's alive.

JAD: So Yochai says Tal shoved his way in front of the television cameras and started signing.

MAYA KOSOVER: 12 hours after the—the earthquake ...

JAD: Maya says she got a call from her partner back in Tel Aviv.

MAYA KOSOVER: ... and she said, "They're on the news now. I can see Tal speaking sign language to his parents, saying everything is okay, they're alive, the three babies are with them. And they are waiting to the rescue team to come and take them."

JAD: But what the cameras also captured was this scene that hadn't really been grasped yet.

ROBERT: Because this whole thing has been going on kind of quietly. Now you have an international earthquake, everybody's watching the television, and in the middle of the story there are like 10 Israeli babies and gay people and all these ...

AMIR: It was a lot more than 20 babies.

TAL: ... yeah, it was I think 24 babies.

MOLLY: 24?

ROBERT: Wow!

AMIR: Yes.

MOLLY: Whoa.

AMIR: Because there is another agency there also.

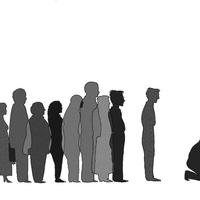

MOLLY: It's like all of a sudden you realize there's this pipeline of babies...

AMIR: Yes.

MOLLY: ... moving from Nepal to Israel.

AMIR: Yeah.

JAD: Maya says when the images of those 24 babies splashed across Israeli TV screens ...

MAYA KOSOVER: It was like the first time that surrogacy was discussed in the Israeli media in such a way.

JAD: She says a huge debate broke out.

MAYA KOSOVER: One side of the argument was okay we are using women and it's—it's unmoral. And from the other hand there was, like, okay, in Israel for gay couples they don't have a lot of choices, I mean...

JAD: And everyone was asking what do we do with all these babies and the surrogates?

MAYA KOSOVER: There was, like, a huge argument in the Israeli media about the questions of there are women that are waiting to—to give birth and we need to bring them to Israel to give birth here because the fathers are here.

JAD: So they would fly the women to Israel, have the baby and then fly them back?

AMIR: Yes, yes.

TAL: There was talk about it.

AMIR: Yeah, they talked about it, but I don't know. think that legally they could not do that.

MOLLY: Because that just—it feels like kidnapping a lady.

YOCHAI MAITAL: Yeah, and so what—what happened was that very quickly Israel sent over a search and rescue and medical aid delegation.

JAD: And all the babies and their parents ...

YOCHAI MAITAL: They were basically just all put on a plane and sort of the process was expedited and they just brought everybody over to Israel.

[NEWS CLIP: Back in Israel, a parade of newborns. They will celebrate together knowing the medical stress they've been through, and very much aware that many in Nepal are still going through it.]

JAD: So what happened to the surrogates? Any idea?

MAYA KOSOVER: They checked with the agency what is the situation with the surrogate mothers and the answer was that two of them are back in India already and they weren't there in their earthquake.

JAD: And what about all the surrogates who were in Nepal but hadn't given birth yet?

MAYA KOSOVER: Yeah, I mean about them there's a big question. I mean, no one knows. There were, like, worried fathers in Israel.

AMIR: It's terrifying. All my thoughts and all my prayers are for the surrogate mother and for their unborn child.

JAD: Tal and Amir made it back to Israel with their babies. They were fine, but there was still a lot of questions.

ROBERT: And if I were one of you guys, I would still be wondering. After all, these—both of these women gave you, as you point out, a remarkable gift. Both of you believe that—you hope rather, both of you hope that that gift was well rewarded and was life changing, but both of you don't know at this point, you're just a little suspicious that maybe it wasn't. Don't you have this funny feeling you need to find out whether they got paid what you thought you paid them? AMIR: Yes. Like, this is why we're so glad that we made the connection with you guys and we heard that you can ...

TAL: Find them, maybe.

AMIR: Yeah.

JAD: So we started kind of a whole new leg of the story.

NILANJANA BHOWMICK: Hello?

MOLLY: Hello?

NILANJANA BHOWMICK: Hi, Molly. Can you hear me?

MOLLY: Yes I can hear you. Ooh, I hear some other things too.

NILANJANA BHOWMICK: Oh, what do you hear?

MOLLY: Actually, it might just be static on the line but it kind of sounded like the ocean.

NILANJANA BHOWMICK: I'll just switch off the fan. Just give me a sec.

JAD: Our producer Molly Webster was able to track down a reporter in India, Nilanjana Bhowmick, and she asked her if she could find those surrogates.

NILANJANA BHOWMICK: Okay, so you had given me a name, right?

MOLLY: Lotus, yeah.

NILANJANA BHOWMICK: Lotus. Lotus has a representative in Nepal. I actually called that person in Nepal and they did tell me, you know, the location of the clinic. And I spoke to the doctor and she said that, "Yes, I will put you in touch with one of the surrogates." And the next morning we were supposed to touch base again but then, you know, she just totally went incommunicado. That's when the same day I opened my mail and there was a mail from Israel, you know, of them asking me, like, just like to stop the search for some time. And I was like, I was so near them.

JAD: As far as we understand what happened was that the doctor contacted Lotus, Lotus contacted Tal and Amir, saying, "Call off the reporters, you're putting these women's lives in danger. If someone in their village sees a reporter hanging around, they'll know those women were surrogates. That's not something these surrogates want people to know. Stop."

JAD: Here's a—here's my understanding, and you guys correct me if I'm wrong, is that we—we had asked someone to look for them, and that person got kind of close and then word got back to the agency and that's created some pressure for us to change. And, you know, that's really what we're sort of staring at right now is how to respond.

AMIR: We heard that there is a real threat on their life because of the culture of the society that they live in. One of them was Muslim. I don't know if—if—if the Muslim society is going to accept the fact that she carried the pregnancy to a gay couple, and ...

TAL: ... to Israelis.

AMIR: And to Israelis, yeah. So ...

ROBERT: That's a very, very weird, very delicate...

JAD: Situation.

AMIR: Yeah, we don't want anything that may hurt the surrogate.

JAD: Well I mean, we want to tell the story. We definitely don't want anyone to get hurt, but I do feel like we have an ethical obligation to hear from the women who do this. If not the specific women in this case, then people who represent their experience to whatever degree it can be represented. It would be—it would feel wrong for that to be a voice that we don't hear.

AMIR: I don't know it's like it's—it's for us it's—it's—we don't want that anybody will contact our surrogate, and if it says that it's not going to be without the story so let's do it because it's not worth it for us.

JAD: Okay. Understood, understood. We won't make any further attempts to contact those two—those two women.

AMIR: Yeah, yeah.

JAD: Just so we're all clear, I think what I'd like to do is to continue to pursue people who have been in similar situations but are not in any way connected to those two women or to you guys.

AMIR: Okay. I mean, again, we need to only make sure that nobody's going to be hurt.

JAD: Absolutely, absolutely.

JAD: That's where we left things with Tal and Amir, and then the story changed—a lot. That's coming up.

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich

MOLLY: I'm Molly Webster.

JAD: This is Radiolab, and we will return now to our collaboration with Israel Story producers Maya Kosover and Yochai Maital. The story of Tal and Amir and their three babies. Now that's how it started for us, it was a story of two guys trying to have some kids, but around the point of the earthquake. the story really shifted for us. I mean, as it did for the entire world, really.

ROBERT: Because we've been concentrating the tale so far on the fathers, but with 24-some odd babies, that's an awful lot of women.

JAD: Who had to carry those babies.

ROBERT: So what could they be thinking? What is the story about them?

JAD: How are they feeling about this transaction? How much are they getting? Will it actually change their life? These are some of the questions we had. We gave those questions to Molly and she sort of ran with it.

ROBERT: Yeah.

MOLLY: Yeah, so in the months after the earthquake, I guess you could say, like, the political situation in Nepal changed, how everyone started looking at surrogacy changed. Once everyone saw these pictures of all these babies outside the Israeli Embassy being put on airplanes and sent back to Israel it just cracked open this huge debate, not just back in Israel but in Nepal and India, even internationally. Basically, you had groups coming out and saying, like, you know, the feminists were saying this is exploitation and we're just using these women for their wombs, and there were op-ed articles about should we be shifting women across borders? Is this the way you want to do surrogacy? And then sort of the next thing that happens, like three weeks after we talked to Tal and Amir, is that Nepal actually decided to ban surrogacy.

ROBERT: Completely?

MOLLY: Completely for both straights, for both same-sex couples, foreign couples, local couples, and for—for Nepali women couldn't do it, and Indian women couldn't come into their borders and do it.

JAD: No more surrogacy, no more loopholes.

MOLLY: No more surrogacy, no more loopholes. But then the confusion was that they banned surrogacy but there were still pregnant surrogates on the ground. And so they sort of existed in this gray zone, and in the midst of that was when we went out to try and find surrogates. In Nepal all of the surrogates are kept in what are called "shelter houses," which are just like houses that agencies rent out that have a lot of pregnant women.

ROBERT: Even though this is banned? They're still—they still have these houses.

MOLLY: Yes, they're still—they still have the houses. Like, the rumors are that they moved the houses further away from the city center, like, to attract less attention, and so we found a Nepali reporter ...

BHRIKUTI RAI: I'm Bhrikuti Rai, and I'm a freelance journalist based in Kathmandu.

MOLLY: ... to go try and get into one of these shelter houses.

BHRIKUTI RAI: So the shelter house is actually quite far from the main city center, almost half an hour or 40 minutes drive from Kathmandu. It's on a—on a hilltop because these are the outskirts of Kathmandu where new settlements have just started. So it was actually a school building which they turned into a shelter because I think the school had left after the earthquake. The moment I reached the first floor I was so surprised. It was very noisy, a lot of children playing around. And it turns out a lot of women bring in their young children if they're too young to be left alone.

MOLLY: Really?

BHRIKUTI RAI: Yeah.

MOLLY: And how many women were there?

BHRIKUTI RAI: There were around, I think, 20 or 22 women there.

MOLLY: 20 or 22 women on the first floor of this building?

BHRIKUTI RAI: Yeah.

MOLLY: This shelter house was run by another Israeli agency, so not Lotus but a different one, and we're guessing that most of the women were carrying babies for Israeli couples.

BHRIKUTI RAI: And at least the women I saw who were outside their room or who had their doors open, they seemed to be around 30 to early 40s.

MOLLY: Really?

BHRIKUTI RAI: Yeah. And I mean, the first time I saw—the first woman I talked to, she was wearing, like, a mustard color sari, she had some bangles. All the women had some bangles in their hands.

MOLLY: She said she was 36 years old, from Kolkata. She has two girls. Bhrikuti asked how old are your girls, and she said 8 and 12. And then Bhrikuti asked, like, why are you doing this and the woman said, "Oh, I'm doing it for them."

BHRIKUTI RAI: It's because, you know, we have a lot of financial problem. My husband is a rickshaw driver and we don't make enough and she worked as a maid in Delhi.

MOLLY: And ultimately, she said, she had no other way to raise money for her daughters to get married because in Hindu weddings the bride's family pays off the groom in the form of a dowry. And the plan was to use the money from surrogacy for the dowries. She'd been in Kathmandu for three months, so she was in her first trimester, and when Bhrikuti asked her does she know who the baby is for, she said no, but she knows it's not hers. And actually, all the women that Bhrikuti talked to were very, very clear about this. This is a job.

BHRIKUTI RAI: The second woman I talked to ...

MOLLY: 30 years old, also a maid in Delhi, also two daughters.

BHRIKUTI RAI: She looked all dressed up, she was all ready to—as if she was about to leave somewhere, and then I realized, okay, her husband is here.

MOLLY: She had just given birth, and she put the job sentiment pretty plainly. So she said—and I'm translating here—"I will give gladly. I will give the baby from my womb. If I will think this is my baby, then how will it work? I have two children, I cannot take this child home. I will have to give. I have no sadness, no problem." Anytime Bhrikuti asked these women, "Are you conflicted? Will you have trouble giving the baby up?" She always got the same answer.

BHRIKUTI RAI: They all say that they would happily give away the child and one of them even said, "If the baby comes out right I'll just give it right away." And then she laughed.

MOLLY: Did you get a sense that these women didn't want it known that they were doing this?

BHRIKUTI RAI: I mean, some of them did and some of them didn't, because some women were like ...

MOLLY: They said, like, now that I'm here, my neighbors, my family, everyone knows. And then when Bhrikuti asked her, you know, do they have an opinion, is it right or wrong? She answered, "No. I'm here for the money, so I would not listen to any opinions. If it was wrong I would not come here."

BHRIKUTI RAI: But some of them were like, "Why would I tell anyone," you know? There was one particular woman ...

MOLLY: 32 years old.

BHRIKUTI RAI: Very cheerful, nail polish on, and she had, like, this pink lipstick on.

MOLLY: She said, "People in my village simply do not believe these things, that one can have children by getting injected or taking medicine. They won't believe this."

BHRIKUTI RAI: She kind of drew parallels with how some of the people in her village had done something similar when they bred cows or fishes. She said, like, maybe they'll understand, but my family will not understand.

MOLLY: She says, "I have told lies to them."

JAD: So how much in the end do they make?

BHRIKUTI RAI: I asked them ...

MOLLY: How much money do you get here?

BHRIKUTI RAI: I talked to four women, and the figure was the same.

MOLLY: 3.5 lakhs.

JAD: What does that mean in—in dollars?

MOLLY: So if you do the conversion today it's $5,300 US. And the way it works is that they get paid a small amount of money every month that they're pregnant, and then at the end they get a lump sum. Bhrikuti said that for these women at the end of the pregnancy that lump sum ...

BHRIKUTI RAI: Is like, let's say, around two or three thousand dollars.

MOLLY: Which is the amount that Tal and Amir heard outside the embassy.

BHRIKUTI RAI: The total sum that they have when they go back home is quite—you know, it's not a lot.

JAD: So five-ish thousand dollars is what you're hearing.

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: Wow, that's a difference.

MOLLY: To sort of see if this was a number that was just coming out of that shelter house or if it was something that was like the going rate, I guess, we talked to six surrogates who were in India. That same rate, around $5,000, kept coming up. And we did hear a range from one surrogate, and this was about a friend of hers, we heard as low as $1,000.

JAD: A surrogate getting only $1,000 for a pregnancy?

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: Hello?

TAL: Hello, this is Jerusalem calling.

MOLLY: Hi, this is New York answering.

JAD: Ultimately we took this information back to Tal and Amir, because this was originally their question.

AMIR: Yeah.

ROBERT: So let's talk about the money part now.

MOLLY: All right, so the last time we talked to you, you thought you were paying your surrogates $12,000, around-ish. We've been off reporting, and it seems like the number that's coming up most consistently for what surrogates are reporting as their rate is $5,300 US.

AMIR: What?

TAL: It's too low.

AMIR: It's too low. Really?

MOLLY: Yeah.

TAL: I want to cry.

MOLLY: We explained to them that if you actually look at the contract, the line that looks like it's payment straight to the surrogate doesn't actually say this is payment for the surrogate, it says, "This is payment to surrogacy services." And it's sort of like once you add in that second word it opens the door to all kinds of things.

AMIR: She's getting less than half. It's very—it's like, we feel like suckers.

TAL: So who will get the money?

AMIR: So who got the money?

MOLLY: That question, it hung in the air for a few weeks, until ...

DANA MAGDASSI: I have around seven minutes before I go into something. I'm just in my car now.

MOLLY: I was finally able to talk to Dana Magdassi, who is the head of Lotus, which is the agency that Tal and Amir used in Nepal. She had just—the morning I talked to her, she had just flown in from Nepal to Israel, and I caught her in a car on her way back to the airport and she was gonna fly off to Australia. And I asked her, "How much do the surrogates actually get paid?"

DANA MAGDASSI: I can tell you truly that I worked in India and Nepal since 2010, and I cannot tell you exactly how much the surrogate is holding in her hand at the end of the procedure because we don't transfer the funds to the surrogate herself.

MOLLY: She's saying she has no idea. And the reason she has no idea is because—she said this, and other agencies I spoke to said this, is when you're working on the ground in foreign countries under the umbrella of surrogacy you are dealing with a lot of middle men, and the middle men have middle men, and there are sub middle men. The—the people who find the women in India, who get all the paperwork done, who get them to the border, who get them over the border, who then bring them to Nepal. Someone meets them in Kathmandu, gets them to the shelter house. And all those people, they need to get paid.

DANA MAGDASSI: I—I truly can tell you that I truly don't know, after the agent, you know, how much the surrogates they have in their hand. We don't come and ask the agent exactly how much goes for her compensation, exactly how much goes for her allowance. We don't go into that. I can tell you that ...

MOLLY: Well, I guess I was thinking about—I would feel conflicted as the head of an agency to be like, "I think the money is going to some people, but I just don't know." Like, I think that would niggle at me.

DANA MAGDASSI: Yeah? Well, that's a good thing that you're doing what you're doing and I'm doing what I'm doing, you know? Because you can't look at the whole world and say, "Okay, I'm going to make it brighter.” I cannot deal with all the problems in the world. We are trying to give them as much as possible.

TAL: We paid the money for this woman gets a life and—and now we understand it's not exactly like that.

AMIR: It's not right.

ROBERT: I mean that's the real—I think the deep question here, underneath after everything is over is when—when we do a generous thing, like we give people families who couldn't have families before, but that becomes a business, is there something about the business of making a family that is always gonna be a little troubling, and there are no perfect ways to do this? Or is there a way to pull this off in some—I just don't know.

AMIR: I mean, like, I still have three more embryos that are in the freezer in the Nepal. I don't know if the next time I would not do the process maybe in the States.

MOLLY: The US is, like, an entirely different surrogacy scene which we're just not gonna get into here, but the interesting thing that—that Dana said, and a head of another agency, was that they think that in the next, like, five to ten years the US will be one of the only countries where surrogacy is still happening.

DANA MAGDASSI: Things are closing down. Most of the things are closing down.

MOLLY: So obviously, Nepal has a ban. Thailand. It looks like in a few days after this piece comes out India may ban it for foreigners. Cambodia, there's rumors that they're about to ban it, and even in Canada there are talks of new restrictions on surrogacy. And this is—these are bans, like, not just for same-sex couples but hetero couples, single people, everybody.

JAD: Oh wow. And the main reason for all these bans and restrictions is worries about exploiting women?

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: I feel weird about that a little bit, though.

ROBERT: Because?

JAD: Because, if you're—if you're trying to—as we heard, these women are making a business decision. Whether or not we agree with it, that's an entirely separate thing. They're—they seem—they seem like they're making a decision, then we're gonna take it away in order to protect them feels, I don't know.

MOLLY: It's funny, because at times it also feels—it—you just think like, okay, these women can decide how they're gonna use their own bodies.

JAD: Right, it's a little like—it's a little bit like the abortion debate, in a way.

MOLLY: Mm-hmm. It totally is.

ROBERT: Well, but by the same token it's—it's—it's not wrong for a society to say, "Hey, there's certain things we just won't allow. We won't give you that choice, because we—we find that the choice itself is wrong."

MOLLY: Mm-hmm. I mean, it's fair. But, like, one of the arguments against banning it is that—is that there's still a demand for surrogacy, and that that's not gonna go away, and so it just pushes this system underground. And so ...

ROBERT: In that way it's a lot like abortion.

MOLLY: And—and then that way it's a lot, you know, shadier.

JAD: Yeah.

MOLLY: But the other thing was is that then Bhrikuti actually went and talked to the women about, like, what this job does for them. Like, okay, so it's not the crazy amount of money we thought it might have been. It's $5,000. Like, what does that do for you? One woman said ...

BHRIKUTI RAI: That, you know, when I get this money I'm going to go back home and start something on my own. Start a small shop, do my own little enterprise.

MOLLY: The other women?

BHRIKUTI RAI: All of them wanted to use this money to build a house, buy some land.

JAD: Can you buy a plot of land in New Delhi for five grand?

MOLLY: You definitely cannot get a plot of land in New Delhi for five grand. But what these women do is they take the money and they go back to their original village and they use it there to buy a small plot of land. And that's totally doable and it's actually no small feat.

BHRIKUTI RAI: Having that ownership of land is so important in our societies in South Asia. MOLLY: Once you own land in South Asia it raises your, like, socioeconomic status. It's something that's passed down through generations, so you're, like, creating something for your family. And if you're one of the women that maybe already have land, the thing you can do with that $5,000 is build a house on it.

BHRIKUTI RAI: It's a very small, like, mud house or you know ...

MOLLY: Keep in mind, like, these women, their day jobs are all maids, right? And so they make less than $100 a month.

BHRIKUTI RAI: They said that had it not been for this, I mean they would have never—I mean, probably never owned this much money at a single chance.

MOLLY: But more than that, like, when you go into this, or at least when I went into this, the thing that I expected to see was like, okay, these are poor, desperate women that are being forced into this. Like, right? They've been dragged across the border. And I think the thing that I was surprised to see when I looked at the transcripts was that even though these women don't have a lot of options, and yes they are poor, they had chosen to do this. Out of the limited options that they had, they looked at them all and they thought, like, "This is the thing that I'm gonna do to get what I want." It felt like these women were making a choice.

BHRIKUTI RAI: I asked them, "What if you were given a chance to go abroad, let's say, Dubai or Qatar?" Because a lot of women from India and Nepal, they go there. One of them said that, you know ...

MOLLY: Like, why would I do that?

BHRIKUTI RAI: That would be a very far away.

MOLLY: She says that here the kids can come, their husbands can visit.

BHRIKUTI RAI: They're fed well.

MOLLY: The surrogates get good medical care.

BHRIKUTI RAI: They're taken care of during the whole nine months.

MOLLY: And—and for those whole nine months they're sending money back home, and back home there's one less mouth to feed.

BHRIKUTI RAI: I think, you know, we—I mean, the way we pass judgment, you know, you just pity on these women, but I think they've—they are very aware of what they're doing. They might be exploited to some level like you said, but it seems like the women are—are—in some ways they are in charge of deciding how they want their life to be, and we don't have to look at them with—with pity.

MOLLY: The last woman that Bhrikuti spoke to, she was a 32-year-old woman from Darjeeling. She spoke in Nepali and she told Bhrikuti, "I came here in March. My embryo transfer was done once, but I don't know if it was due to the earthquake or something else, but it didn't get a heartbeat, and it got washed."

BHRIKUTI RAI: She said that she lost the fetus in two months. And they tried it twice on her.

MOLLY: Bhrikuti: How did you feel when the child got washed? Surrogate: I felt bad. What to say. It felt like it was my own. And they won't give money if it's unsuccessful.

MOLLY: Wow, wait. She—I'm like—I didn't know, if you miscarry you don't get paid?

BHRIKUTI RAI: Yes, yes, yes.

MOLLY: She says it's treated like a business. You get paid for every month you successfully carry, and if you do lose the baby, depending on where it is in the pregnancy, part of the money is refunded to the intended parents. Surrogate: Most of my friends had successful stories to share back in Delhi. Some of my friends made a house with the money, some bought land. I felt good. She basically said she wishes she had done this earlier, because now with the ban she was being sent back to her village.

BHRIKUTI RAI: She was still weeping a little of what could have been if she was—you know, if the eggs were healthy enough, if her health was all right.

MOLLY: Bhrikuti: Will you come again if this opens back up and try again? Surrogate: Yes, I will come.

JAD: Producer Molly Webster.

ROBERT: There's something on your face that says we're not quite done here.

JAD: No, we're done, we're done, we're done.

ROBERT: No, no, no. Say—say what's on your mind.

JAD: Well, I was thinking. I'm thinking about all the different ways we've thought about this story along the way of making it. I mean, you can read it as, like, this is a story about the business of family making, the outsourcing of babies, you can hear it as a story about exploitation, all these different things are happening in the story.

ROBERT: They are.

JAD: But it occurs to me that this is also a story about the inventiveness of people in some weird way.

ROBERT: Invent. You mean—what do you mean by that?

JAD: I guess, what I mean is, like, the way that cultures will cross fertilize in these really unexpected—like, okay, these are—these are two ...

ROBERT: That's true.

JAD: These are two sets of needs that are sort of reaching out and finding each other half a world away. And there's a kind of symbiotic benefit, even while it's troubling and maybe unfair. But it's still kind of there. And like, so I—I feel like we could talk about this story in any number of ways, but I also feel like one of the things that's happened here is this is a story about dreams, and about aspiring to have a better life, and how in this case those aspirations meet in this really uncomfortable transaction.

ROBERT: Yeah. Yeah. Well, let's thank people. That's what we should do next. Let's thank them.

JAD: Yeah.

MOLLY: So many people.

JAD: Oh God.

ROBERT: Okay.

JAD: Well, first we should—we should begin by thanking the posse at Israel Story and Maya Kosover. We have just—we went in deep with those guys for this story. Check them out, it's really cool stuff at PRX.org and IsraelStory.org. What was the one you were just telling us about?

MOLLY: Oh, I love this one.

ROBERT: There—there's a story that they did last season in which they went to every town in Israel that has Herzl Street—Herzl is like the George Washington of Israel. They all have Herzl Streets. They knocked on 48, because Israel was founded in '48. They go knock knock, who's there? And they open the door and they interview whoever is on the other side of the door. It's just a wonderful, cool idea, and they get to meet a crazy quilt of Israelis.

JAD: Yeah, well huge thanks to the Israel Story team and to Barry Finkel.

ROBERT: Yes.

MOLLY: And to our reporters in India, Nilanjana Bhowmick, and in Nepal, Bhrikuti Rai. And the International Reporting Project for connecting us with porters and translators in different countries.

JAD: We talked to a lot of agencies for the story, surrogacy agencies. Special thanks to Doron Mamet and Dr. Nayna Patel.

MOLLY: To our translators Tom Wasserman, Aya Keefe, Karthik Ravindra, Turna Ray France, and Adhikaar, which is a Nepali community organization out of Ridgewood, Queens. And thanks to Ivan Zimmerman.

ROBERT: And for music, special thanks to Nazgiwa and to The Balkan Beat Box.

JAD: We had production help for this story from Andy Mills, and this piece was produced and reported by Molly Webster. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

MOLLY: I'm Molly Webster.

JAD: Thanks for listening. Oh, one last note: we should tell you that Tal and Amir did meet their surrogates very briefly one time, and it's kind of a cool moment. We couldn't figure out where to put it in this story, but we have that scene on our website at Radiolab.org, and it's worth listening to.

[ANSWERING MACHINE: Message five, from phone number ...]

[MAYA KOSOVER: Hi. This is Maya Kosover, calling you again because I had a mistake last time.]

[BHRIKUTI RAI: Hello, I'm Bhrikuti Rai, and I'm a journalist from Kathmandu, Nepal.]

[YOCHAI MAITAL: Hi, this is Yochai Maital from Tel Aviv calling to read the credits.]

[MAYA KOSOVER: Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad.]

[YOCHAI MAITAL: Our staff includes Brenda Farrell, David Gebel, Dylan Keefe, Matt Kielty, Robert Krulwich ...]

[BHRIKUTI RAI: ... Andy Mills, Latif Nasser, Kelsey Padgett ...]

[MAYA KOSOVER: ... Arianne Wack, Molly Webster ...]

[YOCHAI MAITAL: ... Soren Wheeler and Jamie York.]

[MAYA KOSOVER: With help from Simon Adler and Alexandra Leigh Young.]

[BHRIKUTI RAI: Abigail Keel and Alexander Gamme.]

[YOCHAI MAITAL: Our fact-checkers are Eva Dasher and Michelle Harris. All right. I hope that was good.]

[MAYA KOSOVER: Bye bye.]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.