Jun 11, 2021

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey y'all. I just want to play you a promo for a project that's coming that we are very excited about, starting next week actually.

SHIMA OLIAEE: This is a story of a man who changed your world.

PROMO CLIP: Oh wow! See? I woulda claimed this brother right here.

PROMO CLIP: This dude – good God. Why, why don't we have like three movies about this dude. Record owner. Lawyer. I mean he is like the vocational MacGyver.

PROMO CLIP: This is how America invades the world.

PROMO CLIP: This is the greatest music of all time.

SHIMA: But then…

PROMO CLIP: It's like, poof!

SHIMA: Vanished.

PROMO CLIP: Somebody pretending to be somebody that they're not.

PROMO CLIP: I need to think about why but when this Shima was telling me this story all I could think was, oh that's the white boy right there.

PROMO CLIP: That's hilarious to me.

PROMO CLIP: I don't know what JC is talking about. This looks like a Black man.

PROMO CLIP: I want you to see what I see.

PROMO CLIP: Once I was at a festival and some guy came up to me and he said, ‘What are you? What are you?'

PROMO CLIP: My parents put me in front of a mirror. They said that I asked, ‘What, what am I?'

JAD: It's the story of an American riddle.

PROMO CLIP: It's a mystery.

JAD: Wrapped in a family secret.

PROMO CLIP: It's a mystery.

SHIMA: The vanishing of Harry Pace.

PROMO CLIP: A new miniseries from the people that brought you Dolly Parton's America.

SHIMA: Jad Abumrad.

JAD: And Shima Oliaee.

SHIMA: Coming soon to Radiolab.

JAD: That lands next week right here. Okay. Now onto the podcast. This podcast contains some content and language that might be upsetting for sensitive listeners or young children. And – but we do hope you listen cus it's pretty awesome. And it comes to you from the duo of Annie McEwen and Matt Kielty.

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

ANNIE MCEWEN: Uhh. Okay. So how should I start this thingy?

MATT KIELTY: I don't know.

ANNIE: I could ask – oh –

MATT: Probably—uh huh.

ANNIE: I think this all came out of a question that I had.

MATT: Oh sure.

ANNIE: How does a baby take its first breath?

MATT: How does a baby ...

ANNIE: Like a fetus is spending all this time inside the womb. Right?

MATT: Right.

ANNIE: And that – that is like a water world. But then it comes out of the mom and all of a sudden it can breathe in this air world. That's a crazy transition.

MATT: Yeah, it's weird. I guess I would assume the transition is essentially like water world-breathing, water world-breathing, born. It's now just breathing differently.

[Laughter]

ANNIE: Okay, well, do you find that at all—are you at all curious or interested in finding out how it actually works?

MATT: No, I think I got it.

ANNIE: Okay, well I'm gonna tell you anyway because the true answer is totally bananas and I just could—I can't—anyway. I'll just tell you it.

MATT: Tell me.

ANNIE: Okay. First, just to set it up, let's just review how you and I are breathing right now.

MATT: Okay.

ANNIE: So as you might remember from elementary school, this whole thing is like a little dosey-doe between the lungs and the heart.

MATT: Mm-hmm.

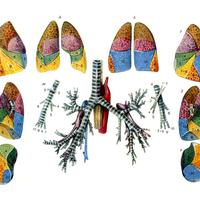

ANNIE: Okay so, blue blood—blood low in oxygen—enters the right side of our heart. From there it gets [whooo] pushed to the lungs, which are [inhale] filling with air [inhale]. Oxygen hops on the blood, CO2 hops off [boop, boop].

MATT: Okay, okay, okay.

ANNIE: Returning to the heart, the blood is bright red in color because it is filled with oxygen.

MATT: Cool.

ANNIE: It is gonna enter the left side of the heart this time—not the right, it's gonna go to the other side of the heart. And then from there the red blood gets [phlew] fired out around the body. It's gonna go to the brain, our legs, our arms, our organs. It's just like gotta deliver it's little oxygen parcels to all our cells.

MATT: All our cells.

ANNIE: Mmhmm. [clears throat] And one more thing [coughs], one thing the—[coughs] so we have in our hearts, so we have these two different sides to it, the right and the left.

MATT: Yeah.

ANNIE: Between these two sides, is a wall. And the red and the blue blood just doesn't mix. Like one side of the heart has the stuff that needs oxygen, the other side of the heart has the stuff that has oxygen.

MATT: Right.

ANNIE: Okay, now we're going to learn how a fetus in a womb breathes. Cus it's very different.

RISHI DESAI: Right. I mean the baby is surrounded by water.

ANNIE: Pediatric infectious disease doctor, Rishi Desai.

RISHI DESAI: And its lungs are full of water.

MATT: Oh.

ANNIE: So, you're not going to get any oxygen from them. But that's okay because instead, of course, for a fetus the oxygen comes from…

RISHI DESAI: Mom.

ANNIE: The mother.

MATT: Right, she does the process you just laid out.

ANNIE: Yep and then…

RISHI DESAI: This wonderful oxygenated blood, that's bright red…

ANNIE: Gets sent down to the placenta. The placenta grabs the oxygen and oxygen and puts it into the fetus blood. Okay so things get a little weird here.

RISHI DESAI: Absolutely.

ANNIE: Red blood leaves the placenta through the umbilical cord…

RISHI DESAI: Goes in the belly button.

ANNIE: And then through a small special tube, a baby tube, that you and I no longer have.

MATT: Weird.

ANNIE: It gets shunted into a giant vein that zooms it up to the heart.

RISHI DESAI: It goes into the right atrium, which is where blood normally goes.

ANNIE: Now, if it was you and me, this would then go to the lungs, but it doesn't go to the lungs because the lungs are just pretty much useless.

RISHI DESAI: The lungs are full of water, right?

ANNIE: They're just hanging there like these soggy raisins.

MATT: This sounds disgusting.

ANNIE: So instead of going to the lungs, that blood goes through…

RISHI DESAI: Trap door.

MATT: Oh.

ANNIE: There's a door.

RISHI DESAI: In the heart.

MATT: In the heart?

ANNIE: There's a door in the wall of the heart.

RISHI DESAI: Between the two atriums, left and right.

ANNIE: In you and me, the two atria are completely separate, walled off. But in the baby, there is this special little door.

MATT: Okay…

ANNIE: It has a special little flap that opens one way.

RISHI DESAI: That little trap door is flopped open.

ANNIE: So the blood all mixes together and you've got this combination of fresh, you know, oxygenated blood from the placenta and old blood from the rest of the baby's body.

RISHI DESAI: Purplish, maroonish blood, right?

ANNIE: Which then gets pumped out to the rest of the baby body. Goes to the brain, goes to the legs. Goes and nurtures its cells, blah, blah, blah, blah, blah. Eventually, it gets back into the placenta, where the carbon dioxide hops off…

RISHI DESAI: And then mom will carry that in her blood …

ANNIE: Oh man.

RISHI DESAI: To her own right atrium and then to her own lungs and then breathe that out.

MATT: Wow.

ANNIE: Got it?

MATT: Got it.

ANNIE: Got it, okay. So this system with the special baby tube and the trap door heart and the mixing blood and all that, at the moment the baby is born has to somehow transform into the system that you and I have…

RISHI DESAI: Within seconds.

MATT: Whoa.

ANNIE: Okay, so let's go to—or do you have any questions or can we go to labor?

MATT: No, no, no, yeah. It all makes sense.

ANNIE: Labor, labor, labor. Okay. Um bah, bah, bah, bah, bah. Labor begins.

RISHI DESAI: As mom's squeezing and as the baby is coming through the birth canal, it's a little bit like wringing a towel dry.

ANNIE: All that squeezing and squishing is pushing this water out of the baby's lungs and…

RISHI DESAI: Into the baby's body.

MATT: Wait, what?

ANNIE: Like we just kind of absorb the water. Like our bodies are like [woop].

MATT: Wait—Internally?

ANNIE: Yes!

MATT: Weird.

ANNIE: Okay so labor, labor, labor, labor. Squish, squish, squish, squish, squish. And then pooh!

MATT: Bah!

ANNIE: The baby comes out of the mother.

RISHI DESAI: The moment a baby is born, it's extremely wet.

ANNIE: And for the first time in its life, it's cold. It's never been cold before.

MATT: Oh.

ANNIE: Actually, if babies aren't dried and swaddled...

RISHI DESAI: The baby can lose a lot of heat right away and it can die from hypothermia very quickly.

MATT: Oh my god. I never thought of the shock that is.

ANNIE: Yeah. But it's also useful.

RISHI DESAI: When that cold hits…

ANNIE: The skin sends little signals to the baby's breathing center in the nervous system. And this breathing center is just waking up. It's like someone is rapping loudly on its bedroom door, wake up. Wake up! It's time! And it's all groggy, like wait, what do I—?

MATT: [Laughs]

ANNIE: Okay, as that's happening, the umbilical cord that has been supplying this baby its oxygen, its nutrients, its everything, is…

RISHI DESAI: Getting super tight.

ANNIE: This thing is already beginning to close.

MATT: That's insane.

RISHI DESAI: So, there's no blood coming in through that umbilical vein.

ANNIE: That means there's no oxygen getting to the baby but it also means that that CO2 in the body is beginning to build.

MATT: The baby is suffocating?

ANNIE: Well, a baby comes out and looks blue, right?

MATT: Oh.

ANNIE: It's blue because it's not breathing yet.

MATT: Huh.

ANNIE: It's like, it's never breathed in its life.

RISHI DESAI: But this baby, taking a breath, it has to happen. And it has to happen fast.

ANNIE: Meanwhile, the carbon dioxide levels are rising. Until finally that little breathing center woken up by the cold skin snaps into action. And…

RISHI DESAI: All of sudden…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mom: Should I be pushing?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Nurse: Mhmm. Little bit of push.]

RISHI DESAI: The brain triggers…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mom: Oh my god.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]]

RISHI DESAI: The baby takes in a big breath. And with that breath…

ANNIE: The nervous system is like [inhales]…go! As the oxygen hits the lungs…

RISHI DESAI: All the dominos start falling.

ANNIE: All the muscles keeping blood out of the heart.

RISHI DESAI: In unison, relax.

ANNIE: Blood is just rushing into the lungs, picking up all this fresh oxygen. The lungs are opening up like two sails filling with wind. The blood then rushes from the lungs back to the heart as it enters the left side, that door that's been pushed open the whole time…

RISHI DESAI: Boom.

ANNIE: Slams shut.

RISHI DESAI: The wall is sealed.

ANNIE: The heart is divided.

RISHI DESAI: Now you've got no mixing anymore. That door will never open again.

ANNIE: And that special baby tube I mentioned starts to close.

RISHI DESAI: Protein is kind of like sewing it shut.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mom: [Laughing] Oh my...]

MATT: Wow.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Nurse: How're you doing?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Nurse: Hey buddy.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mom: Oh my gosh.]

ANNIE: The baby is now breathing on its own.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mom: Hey buddy]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Nurse: So, it looks like he's got a little of this…]

MATT: It's funny because it is a little story of the necessity of trauma.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]]

MATT: That the deeply traumatic act of coming into existence in the air breathing land world.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]]

MATT: The severity of it and the harshness of it forces you to adapt.

ANNIE: Right.

MATT: In order to survive.

ANNIE: Right.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Baby: [Baby crying]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Nurse: Let me cover her though…]

ANNIE: Of course, that's just the first breath. Then there's another. And another. And another. And another. And another. And another…

MATT: Alright.

ANNIE: I'm Annie McEwen.

MATT: And I'm Matt Kielty.

ANNIE: This is Radiolab. And today we are going to do a show all about breath. About how after that first breath, and the next, and the next breath…

MATT: From the moment you are born to the moment you find yourself in right now, these breaths can be long, they can be shallow, they can be short, they can be quick, they can be harsh, they can be quiet, they can be soft. But like whatever they are, they set some sort of like rhythm in our lives.

ANNIE: Which makes you kind of wonder like, where do those rhythms come from?

MATT: And we just figured this sounds totally like a question for…

ANNIE: Molly Webster.

MATT: Our senior correspondent.

MOLLY WEBSTER: Yeah?

MATT: Oh yeah.

MARK KRASNOW: Oh no.

MOLLY: [Laughs]

MARK KRASNOW: Is that good?

MOLLY: Yeah.

MOLLY: Alright so I ended up talking to this guy.

MARK KRASNOW: Mark Krasnow, Professor of Biochemistry at Stanford University.

MOLLY: Okay, perfect.

MOLLY: So, Mark is a lung researcher.

MARK KRASNOW: It's my favorite topic. It's my favorite topic, obviously.

MOLLY: [Laugh]

MOLLY: And we're going to pick up with him in like the 00's.

MARK KRASNOW: Kind of a natural extension.

MOLLY: So he actually has this question of just like, well what is actually controlling the rhythm of the lungs?

MARK KRASNOW: Exactly.

MOLLY: Like what makes you breathe?

MARK KRASNOW: Exactly. Yeah.

MOLLY: So he starts doing some research and he finds this paper that says if you go to the base of your brain…

MARK KRASNOW: In what's called the brain stem.

MOLLY: It's kind of the space that goes up between that groove --

MATT: Oh, that divot?

MOLLY: That you have at the back of your skull.

ANNIE: Oh yeah.

MATT: Yeah.

MARK KRASNOW: Yeah. Yeah, it's right buried deep below that.

ANNIE: I feel it right now.

MOLLY: And it's right there that Mark learned that there is this little clump of neurons.

MARK KRASNOW: That are actually initiating…

[inhales]

MARK KRASNOW: Each breath.

[Exhale. Inhale. Exhale.]

MOLLY: With every single pulse, they send a signal down the spinal cord.

MARK KRASNOW: To your diaphragm and the tiny muscles between your ribs.

MOLLY: Telling them to expand. And they send another signal, telling them to contract. And this is just what these neurons do.

MARK KRASNOW: They are the pacemaker neurons.

[Exhale]

MATT: Huh.

ANNIE: Huh.

MOLLY: So, there are 86 billion neurons in your brain and it's just this clump of 8,000 that do this vital thing.

ANNIE: That seems very small.

MOLLY: It does seem very small, does it not?

ANNIE: Yes! [laughs]

MARK KRASNOW: And so…

MOLLY: So, Mark came across this paper, actually by this guy named Jack.

MARK KRASNOW: I consider Jack the father of the, of the field.

MOLLY: Just a really quick Jack Feldman shout out.

MATT: Wonderful.

MOLLY: But when Mark came across Jack's research…

MARK KRASNOW: We found out about…

MOLLY: He just had this really simple question.

MARK KRASNOW: Which was, hey, are all of these neurons, are they all the same as one another? Or are they different from one another? And so, we started interrogating these neurons.

MOLLY: And so, he and some colleagues, what they did was they started looking at this group of neurons…

MARK KRASNOW: In a mouse brain.

MOLLY: Under a microscope.

MARK KRASNOW: And…

MOLLY: What had seemed to be a uniformed mass of beating.

MARK KRASNOW: It turns out these neurons weren't all alike. There are over 50 different types—

MOLLY: Really?

MARK KRASNOW: Of a pacemaker neuron.

ANNIE: Huh.

MOLLY: Mark was just like, okay, weird.

MARK KRASNOW: You know, what—why are they different and what do they do that's special?

MOLLY: So to start, in mice, Mark decides to focus on this specific group.

MARK KRASNOW: These 200 neurons from the breathing pacemakers.

MOLLY: And basically, with some molecules and a syringe.

MARK KRASNOW: We can very precisely remove just those neurons.

MOLLY: And so, Mark's team goes in, they shut down the 200 neurons. Mouse is happy, mouse is alive. And basically, what happens is mouse stops sighing.

MATT: What?

MARK KRASNOW: Which was like, woah.

MOLLY: So, I didn't know this but mice sigh.

ANNIE: Aww.

MATT: Huh.

ANNIE: That's so cute.

MOLLY: And so that's just saying like, oh these 200 neurons control sigh.

MARK KRASNOW: And they are the only neurons, apparently, in the brain that have this specific function.

MATT: Weird.

MOLLY: Yes. And that's not all. In another experiment they knocked out, again, like 150 neurons and the rate of exhalation changes. So, like you know you can go [inhale] and you go [exhale]. And you can say I want to exhale for four seconds?

MATT: Mmhmm.

MOLLY: Or your body just does it naturally at some rhythm? They found that when they took out this one group of neurons, the rate of exhalation got much longer.

MATT: Huh.

ANNIE: Huh. Interesting.

MOLLY: And so, they're like, oh, interesting. So, they're starting to put together this little visual map of what all of these different neurons do. They almost have a function, right?

MARK KRASNOW: Yeah, so this was…

MOLLY: And so they, you know, they go to another group of neurons.

MARK KRASNOW: You know, roughly 150 neurons.

MOLLY: Knock them out, but this time…

MARK KRASNOW: Very, very disappointing.

MOLLY: Nothing happens. So like, that's weird. Did really nothing change, you know? And they realize a few days later that something did change.

MARK KRASNOW: That, hey, these mice look chillaxed.

MOLLY: [Laughs]

MARK KRASNOW: They are very calm.

MOLLY: They're just kind of licking their fur and hanging out in place.

MARK KRASNOW: Chill. Mellow.

MOLLY: It's like what are, what are these neurons?

ANNIE: Give me those.

MOLLY: And they start looking at what the neurons are connected to. You know how neurons can have those long tentacle projections? And those let them communicate with other neurons?

MATT: Uh huh.

MOLLY: And realizes that where they actually go is directly to the fight or flight center of the brain.

MATT: Wow.

ANNIE: Oh. Wow. Cool.

MOLLY: And so, the story they put together is that this group of neurons, what it's probably doing is sending updates about the status of the pacemaker to the fight or flight regions, saying like, ‘We're working, everything is okay over here.' And they're sending these little signals, giving it updates and if something's wrong, they can send a thing straight into fight or flight and be like “May day, may day, breath is—breath is a mess.'

MATT: Mmm.

ANNIE: Hmm. Okay.

MOLLY: Like breath is a mess, we need to fix it.

MATT: Huh. I guess I think of it—would it be the other way of like, you see something really scary, fight or flight then sends a signal to the breathe – the breath pacemaker, being like, ‘Pick up the pace?'

MOLLY: Well so—so, this starts where—this is where you can really start tripping off on some cool, gnarly things about breath.

ANNIE: That's what I want to do. [Laughs]

MOLLY: Let's do it!

ANNIE: That's what I'm here for.

MOLLY: Okay, let's do it.

ANNIE: Great.

MOLLY: So, Mark walked me through this very cool thing.

MARK KRASNOW: So, there are two great pacemakers in our body. One that many people know about is the pacemaker of the heart, which, you know, beats every second. And it's—it's located right in the organ that it controls. It's right there in the heart.

MOLLY: So, there's actually pacemaker cells in your heart that do the rhythm of the beating.

MATT: Oh really?

MOLLY: They're directly on the organ that they make beat.

MATT: That's crazy.

MARK KRASNOW: But with breath, the other great pacemaker, it's located far from the organ that it controls. It's located in the brain.

MOLLY: And once you put, once you put breath into the brain, you allow evolution to put more on the breath than just the mechanical function.

ANNIE: Mmm.

MOLLY: Like, it starts getting integrated into the emotional centers of the brain and the anxiety centers of the brain.

MATT: Whoa.

MARK KRASNOW: And those parts of the brain can impact and regulate breath. A sigh. And there's you know, laugh, you know or a cry, or even speech. You know, all of those, those are actually breathing.

MOLLY: So, yes, Matt, to answer your question. You see something scary, a signal gets sent from the fight or flight to the breath pacemaker saying, ‘Pick up the pace,' you know. But, what Mark's research shows is it's going both ways. There's cross talk, there's deep integration happening.

MARK KRASNOW: And the other key aspect of the breathing pacemaker compared to the cardiac pacemaker is you can consciously control the breathing pacemaker.

MOLLY: That's the intr—yeah.

MARK KRASNOW: You can hold your breath, at least for a certain period of time, and you can change the output of the breathing pace—so you can override and alter the breathing pacemaker.

MOLLY: Is that why if I take like a [inhale] [exhale]—like a big deep breath, I can actually calm myself down?

MARK KRASNOW: Yeah, but that is the way that you're getting control of this communication between the breathing pacemaker and the fight or flight neurons.

MATT: Huh.

MOLLY: And so, in talking to Mark, I feel like in a way he almost gave me a scalpel to get inside my own brain and control it.

ANNIE: Ah.

MOLLY: Like if I actually change my breathing, it will change this breath pacemaker region and it will send an ‘I'm chill' signal to the fight or flight directly and it will calm down.

ANNIE: Hmm. Wow. It's like you cross a blood-brain barrier and you're on the ground floor communicating—communicating with the parts.

MATT: Hmm.

MOLLY: Yeah, it just—I was—I just felt like—and so like last night when I couldn't—when I kept waking up, like, when I was sleeping, I was like okay, I'm just going to breathe slowly and then—almost being like, ‘Hi neurons!'

ANNIE: Yeah. [laughs]

MOLLY: ‘Like, I'm breathing slowly now so you can send a signal to fight or flight that I'm okay.' And like I can conduct this whole system. Like, I can work the system.

MATT: This next story is about when the system tries to conduct you.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I saw it on Facebook. It was a Facebook post with Mike Brown's body laying on the ground, with his arms sticking out and his legs sticking out. You see Darren Wilson, who's the police officer, sort of standing over him, looking down on him. So, once I heard about what happened to Mike Brown…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Protester: I said you can't stop the revolution!]

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I was out there.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Crowd: You can't stop the revolution.]

ANNIE: This is Justin Hansford. He's a law professor at Howard University. And back in 2014, he was living just outside Ferguson.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I was mostly curious at first. During the day, it was just a march. People chanting and singing and clapping their hands. But also, there are people who are very upset. They're yelling. They're screaming. They're crying. By the time it starts to get dark, police start telling people which way to walk. Giving people orders. Tell you to go home. They actually have tanks on the streets. Helicopters in the sky.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Police: You're unlawfully assembling.]

JUSTIN HANSFORD: Pretty soon after that, pop, pop, pop, pop, pop. Then you start seeing the gas. People screaming in pain, trying to rub their eyes. I just broke. And bolted.

ANNIE: But after that first night, Justin returned to the protests, again and again.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: Yeah, I would go out everyday, especially during that first, what 10, 14 period. And…

ANNIE: Whenever those canisters began to fly…

JUSTIN HANSFORD: Whenever the tear gas came…

ANNIE: He always did the same thing.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I ran.

ANNIE: I ended up talking to Justin because this past summer, seven years after his experience in Ferguson, at the height of the George Floyd demonstrations, even if you weren't on the streets at night, every morning you were seeing pictures and videos of these massive clouds of smoke hanging over people. It really began to feel like every time there was a demonstration or protest or a march, it would end with tear gas. And I couldn't stop wondering like, how did we get here? How did we get to this place where the go-to weapon for police responding to these protests, is this gas?

ANNIE: Hello?

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: Hello.

ANNIE: And the first thing that popped up was it basically began in WWI.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: Right. First World War, you had trenches...

ANNIE: I learned about all this from Anna Feigenbaum.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: I am an associate professor of digital media and communication at Bournemouth University.

ANNIE: And she said those trenches...

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: They were like protection and a trap, right?

ANNIE: People would just hide in their trenches and then shoot at each other, and then hide in their trenches.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: It was really difficult to advance on either side.

ANNIE: You couldn't move up on the enemy soldiers without getting shot. So, both sides would just end up sitting there. So, the question became how do we get the enemy soldiers out of their trenches? And the answer…

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: Tear gas.

ANNIE: Tear gas.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: France was the first to fire it according to the most agreed historical story of World War I.

ANNIE: August 1914, the French fired tear gas grenades at the German line. Strange smoke crept across no man's land and down into the trenches. And given what tear gas does, we can imagine that the German soldiers started to rub their eyes in pain, tears started streaming down their faces. And then as they breathed the smoke in, they began to cough. They coughed and coughed. Their throats started to burn. Their chest tightened up. And at that point, panic set in. They left the safety of their trenches and began to run. And, of course, then ...

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: You can shoot them.

ANNIE: The French opened fire. And this moment sort of broke the seal for chemical warfare. Soon after Germany brought chlorine gas and mustard gas, these far more harmful gasses to the battlefield. Other countries made and deployed their own gasses. And eventually, gas just became this terror of World War I.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: Right.

ANNIE: So, the First World War ended, what happened?

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: So, you've got people who were like, all gas warfare is inhumane. It creates that kind of psychological torture of the psyche that is just not acceptable.

ANNIE: And the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, you may have heard of it.

MATT: I know all about it.

ANNIE: This is, like, at the end of World War I, the Allies came together to figure out what to do about Germany. But at the same time, part of it was like what do we do about gas?

MATT: Uh huh.

ANNIE: And it basically kicked off this whole debate, which would eventually get all these gasses, including tear gas, banned from use in war.

MATT: Hmm.

ANNIE: But one of the key things they did at the Treaty of Versailles was to make a distinction between the different gasses. So, there was...

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: The really bad kind.

ANNIE: Like chlorine gas.

MATT: Yeah.

ANNIE: Which could straight up kill people.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: And the not so bad kind.

ANNIE: Like tear gas., which eventually got labeled non-lethal.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: Right.

ANNIE: And Anna says…

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: That distinction is really, really important.

ANNIE: Because it left the door open for people to argue that even if we can't use tear gas in the trenches abroad, maybe we can use it on the streets back home. Okay so fast forward to the end of the First World War. There's a recession, there's been a recent influx of Black folks in Northern cities looking for opportunities that they don't have down South. And a lot of white soldiers, just getting back from overseas see these Black folks as threats to their jobs. And in dozens of different cities across the states, gangs of white men roam the streets, burning Black homes and businesses and killing hundreds of Black people. And Black soldiers who'd also recently returned home from war, were fighting back. This became known as the Red Summer of 1919. And in the midst of all this, there was also a wave of labor strikes. And some police forces began writing to the War Department requesting tear gas. This is from the New York Police Department in August 1919...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: It has occurred to me that these gasses might be an efficient agency in suppressing disorder.]

ANNIE: From the Department of Public Safety in Norfolk, Virginia in September...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: In this city where it is possible that we may have a great deal of trouble with the Negro element, such a device, I believe, would work to perfection.]

ANNIE: And the War Department is like, ‘No way.' But these requests, that said, ‘Send us tear gas,' they kept coming. And in the meantime, there were people within the War Department who were thinking, maybe this isn't a bad idea. In particular, there was a general named Amos Fries, who was a huge proponent of tear gas. And he and his network started to arrange these big demos with these police departments.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: So he had, like, 200 police officers go out into a big field. You know, a bunch of police pretended to be protesters and the other police were the police.

ANNIE: The pretend protester police got shot with tear gas. And Amos Fries made sure there were some reporters there to see it.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: In the article, there's these lines of, like, ‘The grown men were crying like babies.'

ANNIE: Showing that just by restricting their breath, he can dominate these guys. Make them run or coward or give up. But the key part of his argument, the thing that made tear gas so special was that …

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: A couple hours later, everyone's gonna be back to normal and fine and you won't have any, you know, blood on your record.

ANNIE: As the riots and labor strikes and civil unrest continued, tear gas, this thing that could control a crowd without killing, started to win the day. And if you search the archives of the New York Times around 1921, 1922…

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Tear Gas Holds Back Mob, Idle Reds Threaten a Tear Gas Revolt, Tear Gas Stops Riot]

ANNIE: You start to see tear gas slowly seep into its pages.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Police Use Tear Gas to Dislodge Maniac]

ANNIE: At first, it's only a few a year.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Tear Bombs Used on Princeton Students, Police Say]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Tear Bombs Scatter Detroit Mob of 5,000, Which Masses Before Anti-Klan Meeting]

ANNIE: By the time you get into the ‘30s…

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Bombs Route Crowd at Negro's Trial, Tear Gas Ends Riot]

ANNIE: There are hundreds of instances of tear gas being used all over the country.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Tear Gas Ends Riot Against Tax Sales. Tear Gas Quells Wilmington Riots]

ANNIE: And so, it got to the point where wherever there was a crowd of unhappy people...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Tear Gas Routs Communists]

ANNIE: There was tear gas.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, John F. Kennedy: The frustration and discord are burning in every city.]

ANNIE: The Civil Rights Movement.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Protests against the war persisted.]

ANNIE: The Anti-Vietnam War protests.

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: The anti-globalization summit had lots of tear gas.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [shooting]]

ANNA FEIGENBAUM: Occupy got super tear gassed.

ANNIE: And I talked to this guy at the Omega Research Foundation, his name is Neil Corney. And part of his job is looking into the use of tear gas worldwide.

MATT: Hmm.

ANNIE: And he told me that in the last 10 years or so, the use of tear gas has just exploded. And that is also of course when the Black Lives Matter Movement really, you know, began and picked up steam. And over that time, Justin Hansford kept showing up at protests. He became a legal observer and even went out to accompany Mike Brown's family to Geneva to testify at the UN. And he says that he probably ran from tear gas about 30 times.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I—there were times when I could not escape it. Multiple times. Really the worst time for me, I was actually in my car.

ANNIE: Oh, wow.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I have asthma. And—you know, a lot of, especially Black kids have asthma, in part because where we've had to grow up. But anyway, I know that if I got tear gas in a major way, it could be lights out. So, I ran to my car. And I couldn't drive through the protesters because the protesters were on the street. So, I had to drive sort of perpendicular to get around where the protest was. Unfortunately, everybody else was trying to do the same thing. So, I was about one block over from where they had deployed the tear gas and I was stuck. I double checked to make sure my windows were—I tried to, like, roll up more. Tried to turn off my vents. I knew when the tear gas had entered the car cus I could recognize the smell, almost like laundry detergent, but it's more pungent. I was panicking a bit because I didn't have my inhaler on me at the time.

ANNIE: Dang.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: And I covered my mouth, but I knew there wasn't much I could do. I was coughing a lot. I was coughing uncontrollably. Tears were coming down. I never knew if it would just hit. Like, I'd have an asthma attack and just hit. Just panic.

ANNIE: As his chest clenched and tightened, as he struggled to breath…

JUSTIN HANSFORD: You're in flight mode. Like, you're frantically searching for what's going to keep you alive and you're not finding it.

ANNIE: It's sort of impossible hearing this story, to not think about that phrase, ‘I can't breathe' that's become a rallying cry for the whole movement. It's sort of sitting over all of this as both a metaphor and literal experience.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: Yeah, I mean it's seared into our minds because the phrase was repeated and gets repeated in people's final moments of their life. It was Eric Garner and George Floyd, it was their last words. And that the chokehold and that position of putting someone prone on the ground with your knee on their back, even if it interferes with their breath.

ANNIE: So, the panic in that moment is in his body, but it's also in the world he lives in and his history.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: You know we have history of lynching in this country. People hanging from trees couldn't breathe. It was often a type of suffocation that happened in our history – it's a legacy of that. It's always a choking.

ANNIE: And all of that settles on Justin in that moment in the car.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I just sort of put my head down and I sort of just steeled myself to take whatever is going to take place.

ANNIE: He says it was in some way a feeling of resignation.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: I was—I was resigned. I have to be honest with you.

ANNIE: But also resolve.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: Imagine me driving my hands on the steering wheel. I smell it and I just start hanging—I just hang my head and just like, shake my head and just say, ‘Alright now, here we go.' So, yeah.

ANNIE: Um, I wish there was, like, a lighter question I can now ask you.

JUSTIN HANSFORD: [laughs] Yeah, ask something light.

ANNIE: What do you do to—what do you do to feel better? What do you do to unplug and relax? Or do you not? Like, or do you just—you just write papers. Or do you have—like, do you have a cat? Like, what do you do? [laughs]

JUSTIN HANSFORD: [laughs] Oh, you know what I like—I like to go jogging. And especially if it's warm outside and there's sun and I will listen to some music. I like to jog when it's very sunny out. I just like to get out there early in the morning, listen to the birds sing for a little while and then just turn up the Janet Jackson and just make it happen.

MATT: In keeping with something lighter.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Matt, do you know what you're talking about? Do you have any idea what you're talking about? [laughter]

ANNIE: Did it turn out that, no, he didn't?

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Yeah.

ANNIE: Wait, who are you? I have no idea who you are. [laughter]

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Me?

MATT: Yeah. Maybe we should, maybe we should back up. If you could, if you could just like say who you are.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Okay, so like when do you want me to start doing this? Like now? [laughter]

MATT: Yeah.

ANNIE: 5, 4 --

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: You guys are nuts. Okay. So I'm Marcia Mogelonsky. I'm the Director of Insight at Mintel Food and Drink.

MATT: Director of Insight?

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Insight. Yes.

ANNIE: What is a Director of Insight?

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: A person who sits on the phone with people like you and talks about where mints came from.

MATT: Which is sort of true because Marcia works for this market research analytics company and she's in the food department.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: I am the category expert for confectionery. So I'm in charge of --

ANNIE: Wow.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Chocolate, gum and mints. Yes. This is like the perfect job.

MATT: When you started, what jumped out to you about mints?

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: What was interesting to me is the—the line between a mint, a candy and a breath freshener is very fuzzy unless you're going for breath freshening strips or what we used to, you know, squirt into our mouths. I don't know if they even exist anymore --

ANNIE: Oh my God.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: But like, Binaca.

MATT: Oh Binaca --

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Binaca --

MATT: Binaca was great.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: And then, then there were those Listerine breath freshening --.

ANNIE: Strips!

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Strips that dissolve on your tongue --

MATT: Oh, those are gross --

ANNIE: Those are awful!

MATT: Those are really weird. Yeah.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: They were really weird and they were gross tasting. But now --

MATT: That feels like some market innovation though.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Oh, it was when it was first launched, but it doesn't really exist anymore. It's been replaced by other innovations like --

MATT: What's—what are the new ones?

ANNIE: Yeah, what's the hot thing right now?

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Mint—Just minty flavored, strong minty flavored everything. Like, like those Altoids that come in strong minty flavors.

ANNIE: M-hmm.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: But this is a really sall—small slice, really small slice of the confectionery industry. This is not, you know, stop traffic, we've got new mint! Because it is intended for two purposes, basically. Well, maybe three. Number one is breath freshening. Number two is to wake yourself up because you're having a slump and you're really bored, so you reach for something little at your desk. You're not going to eat a bag of Doritos when you're having a slump.

MATT: Speak for yourself.

ANNIE: Yeah.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Exactly. But most people are looking for a pick me up and that pick me up could be a chocolate. It could be a cookie. It could be just a mint because you don't want to have anything too big. You just want something different. You want something to chew on.

MATT: And a mint is kind of stimul—it's stimulating --

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: A stimulate. Or you want something to chew on, which is to get rid of nervous tension. Or stop yourself from doing something worse, like eating or smoking.

ANNIE: Right. And Number four is kissing. [laughter]

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Well, yes of course.

MATT: Okay, well so—so last time we spoke, you had said something that totally surprised me. Cus I just called you up being like, I don't know, breath, breath mints, what? Like what's going on? And you said that the market is down.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Yeah. The market for mints and gum, sales have declined. Why have sales declined? It's not because we all want to have stinky breath. Well, that might be part of it. But the major reason is those are really impulse purchases. On the way to work. Getting on the train, before you get on the train, there's a kiosk right by the subway stop. You go, oh, I could use some mints, my breath's a little stinky. So you pick up a package of mints and you throw them in your purse or your pocket or whatever.

ANNIE: Right.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: That doesn't happen anymore because no one's going anywhere! Because you see them and you realize there is a need.

ANNIE: Yeah, right.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: And the need is you have to freshen your breath. You have to freshen your breath because you're going to go have some very garlicky food for supper and then you're going on a date afterwards. Or you're going to work and you have a big meeting and you're going to have to meet the boss. But you happen to have had garlic chicken for lunch, which was a big mistake, believe me.

ANNIE: Garlic everywhere. [laughter]

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Or you're at the bar and you have a drink and then you meet someone and you want to talk to them and you don't want to appear like you've been drinking. You want to have fresher breath.

ANNIE: Oh yeah. At the bar, I wasn't drinking, I swear. Just eating my garlic chicken.

MATT: You can tell by my spearmint breath, I haven't been drinking at all.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Exactly. You don't normally have them, but suddenly you have a reason to buy them.

ANNIE: Yes.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: It's not a planned purchase. It's usually an impromptu purchase.

ANNIE: There's also something like the idea of like, breath mints or something hopeful about that. Like you reach for it because you have a date later or because you have a meeting later. Or there's like you're going to be a person in the world and this is going to help you. And it's going to be like your assist or your life saver or you know, whatever.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Yeah. Yeah.

ANNIE: And so this like lack of reaching for these, like, little hopeful things that will like, you know, push us to be that much better in our day or that much more confident. It's like, just interesting that we're in that time --

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Yeah.

ANNIE: Time right now.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: And I think that things will improve.

ANNIE: Yeah.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: I think that this has just been a blip in the general universe of things. This has been a wholesale change in people's behaviors that people just did not anticipate. No one ever thought we would grind to a halt --

ANNIE: Right?

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Where we spent the past year staring at our own four walls and not meeting people. And going to the movies, going to concerts, going shopping, going socializing, all that stuff just ground to a halt.

ANNIE: Right.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: But I think that things will improve. I think that people are going to be desperate to resume.

ANNIE: Be poppin mints like crazy.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Oh, yeah. And sneezing their way from here to there. So. [laughter] You guys seriously don't sneeze when you eat a strong mint?

MATT: No.

ANNIE: No but what? --

MATT: I do like the idea, though, of like the sign that we've—we're getting out of the darkness is the breath mint rebounding.

MARCIA MOGELONSKY: Yeah. Yeah.

MATT: I ended up calling another retail sales firm. They told me that in the pandemic breath mint sales dropped off by 40%. But that since March with each passing day, they started to see mint sales tick back up.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: Okay, I will count down from 10. I will stop the countdown at 3. Everybody ready? Here we go. 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3. ]

MATT: We're gonna keep breathing.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Didgeridoo]]

ANNIE: Just after this man holds this note for as long as he can.

MATT: Be right back.

[LISTENER: This is Angela Babierres from San Jose, California. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org.]

[JAD: Science reporting on Radiolab is supported in part by Science Sandbox. A Science Foundation initiative dedicated to engaging everyone with the process of science.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [Didgeridoo] [Exhale]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [Applause]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: We have a world record. Congratulations.]

ANNIE: Annie.

MATT: Matt.

ANNIE: Radiolab.

ALICE WONG: Okay. Are you ready?

UNIDENTIFIED PERSON: Yeah. I'm ready.

ALICE WONG: Okay. I sense a disturbance in the air. My chest feels tighter, something is not quite right. And then I see it. Flames are licking the bottoms of trees... hundreds of miles away. From my home in San Francisco, I can sense a wildfire coming before most people because of how my respiratory system is built. My diaphragm, which is slowly weakening over time, gives me a heightened sensitivity to secrets in the air. Because my diaphragm is weak, I use a ventilator to help push the air out of my lungs. Without this machine, my own CO2 would gather in my body and I would die slowly from a buildup of acidic blood. This nearly happened when I was 18 and first experienced respiratory failure. My brain went fuzzy and in the ER, I remember seeing my arterial blood drawn from my body, starved of oxygen. Thick and black as ink. But I clawed my way back and lived to tell the tale, that is, if you are willing to listen.

ALICE WONG: When the coronavirus broke out, many states ranked people like me, who need a machine to breathe, lower down on the list of those deserving medical treatment. New York went even further. According to the ventilator allocation guidelines on the New York State Department of Health's website, it says that hospitals are allowed to take people's personal ventilators and give them to other patients in times of triage if they seek acute care. In essence, they can steal breaths from people like me and give them to others.

ALICE WONG: But my body, that the state calls broken, I call an oracle. It's not just the distant flames that I can see before you. But it's the cold math that calculates the value of my life, an algorithm of expendability, that—whether you realize it or not—can come for you as well.

ALICE WONG: My name is Alice Wong. And I'm a disabled activist, writer and all-around troublemaker.

MATT: Okay so this next thing comes from…

ANNIE: Yeah, you sound great.

MOSI SECRET: Alright.

MATT: Writer Mosi Secret, who typically does some pretty serious journalism.

MOSI SECRET: Yeah, I mean I have mostly done investigative reporting or, or in-depth narrative writing on issues of race or issues of criminal justice. And man, this just sounds like, you know, like—you know, fun.

ANNIE: [Laugh] Imagine that, yeah.

MOSI SECRET: You know, but I will say that this did not end up being a totally silly thing.

MATT: So, thing begins…

MOSI SECRET: Maybe two or three years ago, there was this video that went around…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Funkmaster Flex: Funk Flex, I'm here.]

MOSI SECRET: From Funkmaster Flex's show.

MATT: On Hot 97.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Funkmaster Flex: Hashtag freestyle.]

MATT: And to set up the significance of what you're about to hear. So Flex, he's got a radio show, a lot of rappers come on.

MOSI SECRET: And it's a regular feature that Funkmaster Flex has where people kind of come on and freestyle.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Young M.A: Young M.A here, ‘bout to shut it down on the Funk Flex show.]

MOSI SECRET: And there are a lot of people who are…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, A Boogie wit da Hoodie: “Hey man, A Boogie wit da Hoodie with my man Don Q.”]

MOSI SECRET: A lot of younger, newer rappers who come on and you know, who are doing some—they think they're doing something.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Don Q: Don season. We can curse?]

ARCHIVE CLIP, A Boogie wit da Hoodie: Shit about to go crazy.]

MATT: They think they're doing something. Because in these freestyles…

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [rap music]]

MATT: Which are very, very good. There are moments of…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: Na, na, na, na, na]

MATT: Rappers who are kind of stalling out.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: Hold on. Hold on.]

MATT: Rappers who want to do multiple takes. Rappers who can only go for a minute or two.

MOSI SECRET: And so they're like, okay let's bring in the OG and show them how it's done.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Funkmaster Flex: I mean listen, I like to answer people's demands. I like to come through with what they ask me for.]

MATT: So, this video is a video…

MOSI SECRET: Of…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Funkmaster Flex: Black Thought is here.]

MOSI SECRET: The rapper Black Thought.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Funkmaster Flex: And we're going to—you know what we do in this position.]

MATT: He's sitting at a desk next to Flex. He's got on a beige fedora, sunglasses.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: Let's go Erns.]

MATT: And…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: Let's do it.]

MOSI SECRET: He kind of, like, destroys it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: Uh, I'm sorry for your loss. It's a body dead in the car and it's prob'ly one of yours. The writing all across the window and the walls. Whether it was true or false, we shouldn't have got involved. Remember, we walked past the teacher, take the chalk and laugh. We wrote punishments: I will not talk in class. Now it's pistols punishin' people for talkin' fast. And all these innocent bystanders is haulin' ass…]

MATT: And what unfolds in this freestyle…

MOSI SECRET: Is 10 minutes of him not missing a beat.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: Fools swear they wise, wise men know they foolish. Well, we was headed for the web, even before computers.]

MOSI SECRET: And the beat was very fast and the rhymes were like, intricate.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: I was makin' major moves, my dollar déjà vu. My mission when my ambition was brandishin' a tool. To be a icon, wearin' slippers made of python…”]

MATT: And what you start to see in this video is Black Thought keeps going, it's like about three minutes in…

MOSI SECRET: You can kind of see this motion in his body, like he starts to almost like bounce in his seat.

MATT: At about five minutes…

MOSI SECRET: He breaks a sweat.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: We went from Similac and Enfamil to the Internet and Fentanyl. When all consent was still against the will. I got that detox for y'all, the microphone doctor, Black Deepak Chopra.]

MATT: By six minutes, the sweat is dripping down his face. By seven minutes, you know, this guy is entering a trance.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: Y'all just regular, I'm an apex predator. Brim stay fresh, feathered up, etcetera, never the…]

MATT: By eight minutes, you can see Flex's face, just like, oh shit. By nine minutes, you can tell, he's just pushing it out.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: I'm a bull inside a China shop. Mollywhoppin', watch another cotton pickin' body drop. Every time we rock…]

MATT: And finally, just under 10 minutes, 10 minutes straight, Black Thought lands this freestyle.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: Too much data. I tell a story like fingerprints and blood splatter.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Funkmaster Flex: You see what it is? Black Thought funked with motherfucking take. You just showed what it's supposed to be. CIROC Studios. You mad? Fuck yourselves. Stop the bombs.]

MOSI SECRET: And after that, there were all these discussions like, ooh, you know, is he one of the greatest rappers of all time? Did we not know this? And I was talking to some friends about it—like a lot of people were talking about it—and one of my friends was like, ‘Well, you know he can do that because he can circular breathe.' And I was like, ‘Huh.' That sounds crazy that he can circular breathe while rapping.

[Laughter]

MOSI SECRET: And I was just like, oh, okay, that explains it. That explains it.

MATT: Because for Mosi, he knew the power of circular breathing. As a kid, Mosi got really into jazz when he picked up a saxophone.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [Saxophone jazz music]]

MOSI SECRET: And I was—you know, in the beginning I was really into horn players. You know John Coltrane and Sonny Rollins, these tenor saxophone players. These guys became heroes because that's what I was trying to learn.

MATT: And so as a kid, he had heard about circular breathing.

MOSI SECRET: Almost had this mythic quality, like this kind of superhuman uncanny ability that some people have to sustain sound for minutes and minutes or hours and hours. Like Sonny Rollins, I knew that he could do it. Kind of do these solo improvisations and they were incredible.

MATT: And Mosi always thought if you could just learn how to get there, learn this technique, you could enter this other realm.

MOSI SECRET: But I was not the best practicer.

[Laughter]

MOSI SECRET: And also I just had this feeling that people were listening to me --

MATT: Yeah.

MOSI SECRET: And I felt, you know, a little embarrassed that I wasn't good yet.

ANNIE: Aww. [Laugh]

MOSI SECRET: So…

MATT: Eventually, he put down the sax.

MOSI SECRET: So, I hadn't thought about saxophone or circular breathing for a long time.

MATT: But then…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Funkmaster Flex: Funk Flex, I'm here.]

MOSI SECRET: Huh. That sounds crazy.

MATT: And so…

MOSI SECRET: Talking about this episode that you guys are doing…

MATT: Mosi pitched us this story about the freestyle, about circular breathing, we were just like, yeah?

MOSI SECRET: So…

MATT: He went off reporting.

MOSI SECRET: Basically, internet research.

MATT: Ended up on Reddit.

MOSI SECRET: On this—I read this subreddit where it's like, ‘Oh my god, did you guys see that flow? You know why he can do that, it's because he can circular breathe. And then people were like, ‘Oh man, that's so amazing. That's why he's so great.'

[Laughter]

MOSI SECRET: And then, you know, like a few posts down, there's somebody who comes in. He's like, ‘Well, actually, I play clarinet and it is technically impossible.' It is actually impossible for one to use circular breathing while speaking.

MATT: Huh.

ANNIE: Hmm.

MOSI SECRET: Yeah.

MATT: And I should say really quick, in hindsight, went back and watched the Black Thought video.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: Prob'ly one of yours. The writing all across the window…]

MATT: And was like, Ooooh.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: We walked past the teacher…]

MATT: He's breathing all the time.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: [[breathing]]

MATT: This is a super cut—this is a super cut of him breathing. I didn't count the breaths but it's like a lot—clearly a lot of breaths. Like sort of, he's just breathing like a normal person but doing this extraordinary thing.

MOSI SECRET: Yes. The artistry there is amazing.

MATT: So, like, he is a genius but he's not doing the crazy, godly, mythic thing of circular breathing.

MOSI SECRET: But…

MATT: But then Mosi dropped another bomb.

MOSI SECRET: From what I understand, like, most horn players can do it.

ANNIE: Oh.

MATT: Oh.

MOSI SECRET: I know, sorry.

ANNIE: Wah, wah. No, it's okay. [laughs]

MOSI SECRET: I mean there are videos on YouTube showing you how to do it.

ANNIE: Oh, that's interesting.

MOSI SECRET: So, in Kenny G's how-to video on YouTube, he says--

MATT: Ah, I'm sorry, excuse me?

MOSI SECRET: You have to watch the Kenny G tutorial.

[Laughter]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kenny G: Hello, it's Kenny G here. Welcome to the Rico website.]

MOSI SECRET: Because just everything about it says, you know, 1990s smooth jazz Kenny G.

ANNIE: Yes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kenny G: And it's called circular breathing. It's where you hold a note, and you actually breathe while you're still sustaining the sound. But anyways, this is what happens when you do it right, okay? [Saxophone]]

MOSI SECRET: And then there's stuff like…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: So, what is circular breathing?]

MOSI SECRET: You can circular breathe in ten minutes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: That seems inhuman.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: If you practice it, it comes really, really quickly.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kenny G: So, you can see how I'm breathing through that, I'm not out of air. Now…]

MOSI SECRET: So, it is—there is a little bit of oh, I could have been doing this when I was 12. You know, like damn, this is a lot easier than I thought it was.

MATT: But, is it really?

SHAYA: Hello.

MATT: More people! Hello. How's it going?

MATT: So, Annie and I went out into the world.

SHAYA: We're at the Brooklyn Music School in downtown Brooklyn.

MATT: To a room at the Brooklyn Music School, which had a little vibraphone, piano. And also some flutists.

SHAYA: It's called a head piece.

MATT: There were three of them.

MATT: Your name is?

ADDIE: My name is Adelaide.

MATT: I'm Matt. Nice to meet you.

MATT: There was Addie.

SADIE-LOU: My name is Sadie-Lou.

MATT: Sadie-Lou?

SADIE-LOU: And I like watermelon.

MATT: So Addie, Sadie-Lou, both 10 years old.

MATT: Oh, and Hannah, Hannah. How old are you?

HANNAH: 12.

MATT: And Hannah, the 12 year old.

MATT: And which grade is that?

HANNAH: Seventh.

MATT: Also, there was Shaya, the flute instructor, and a couple parents.

MATT: Did your parents explain to you what--what we're trying to do? Do you know about circular breathing?

SADIE-LOU: No.

HANNAH: I think it's, like, breathing—like, a breathing technique where you're breathing with your nose and your mouth at the same time.

MATT: Exactly.

MOSI SECRET: Yeah. Well, I can actually kind of tell you how to do it.

ANNIE: Okay.

MATT: So Mosi tried to teach us how to do it, and we tried to teach the kids.

MATT: Okay, maybe we should take a second, practice step one.

MOSI SECRET: So, if you just blow up your cheeks.

MATT: Put some air in your mouth cheeks.

MOSI SECRET: And then breathe through your nose while you have that air in your cheeks.

ANNIE: Mhmm.

MATT: Okay. Well, we got some fast learners. Okay. Does everybody feel good about step one?

ADDIE: Yes.

MOSI SECRET: The second thing that you will do is, while you have your cheeks blown up, use your fingers to press in your cheeks…

MATT: Squeezing the air out of your cheeks…

MOSI SECRET: Out of your taut lips.

MATT: Very elegant, little ...

MOSI SECRET: Slowly, I should say. And so the skill is learning to force that air out of your mouth with your cheek muscles --

ANNIE: Wow!

MOSI SECRET: Rather than with your fingers.

MATT: Oh!

MOSI SECRET: And you are doing that at the same time as you are inhaling.

MATT: Okay. Okay. [laughter]

MATT: Okay, how do we feel about step two? Okay, great.

MOSI SECRET: And then the last part is, which is where it gets really difficult --

MATT: How do you refill the cheeks?

MOSI SECRET: Is that—exactly. How do you refill the cheeks?

MATT: So one of the things that we need for this is a straw. So, there's three straws.

MATT: And this is the really tricky part is you have to, while you're pushing the air out with your cheek muscles, you have to inhale to get some more air back in there. And you just keep it going, continuous flow.

MATT: Also, I will hand out—I will hand out jars of water ...

MOSI SECRET: So no, you get a glass, you fill it half with water, you fill your cheeks with air...

MATT: Blow through the straw into the water.

MOSI SECRET: And the way that you know that you're doing it correctly is that the water obviously will bubble, and you want those bubbles to continue --

MATT: Right. Forever.

MOSI SECRET: Yeah, forever.

MATT: Okay. I'll start at three. Three, two, one, breathe.

[bubbling sounds]

MATT: And what we saw was our two 10-year-olds—God love them—after about 20 seconds, when their faces were just, like, pure pushing out air…

ADDIE: Oh my god.

MATT: They took a breath. But then we noticed ...

MATT: Are you—are you already doing it?

MATT: Our 12-year-old, Hannah...

MATT: Go!

ANNIE: Yeah, look at her.

MATT: Was totally doing it.

ADDIE: Hannah, how?

SADIE-LOU: What?

MATT: I think you got it!

SADIE-LOU: Oh Shaya's still going too.

ADDIE: Look at that!

SADIE-LOU: Oh my God!

MATT: Oh Shaya's got – Shaya's got big bubbles over here.

MATT: Shaya the flute instructor picked it up.

ANNIE: I think your mom's a champion.

MATT: Addie's mom got it.

ADDIE: She wants to stop! [laughs]

ANNIE: Woohoo. Good job!

MATT: Mom, that was great! [applause].

ANNIE: That was awesome.

MATT: Whooo!

ADDIE: Nice job, mom.

MATT: So, yeah. Circular breathing. Easy-peasy, fun for the whole family. Although I will say that actually doing it on the flute proved really hard. And to be fair ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kenny G: It only took about 20 years to kind of get it okay.]

MATT: Kenny G said it took him a long time to master it. But yeah, it turns out it's pretty simple.

MOSI SECRET: Yeah.

MATT: I'm just—I'm just wondering, given that and the sort of let down of Black Thought and horn players and whatnot, like, was there anything in your reporting that sort of jumped out to you?

MOSI SECRET: Well, I think that—I mean a lot of it has to do with the idea of the breath. So, like in Western music, especially, or Western theory kind of revolves around the phrase, the musical phrase. And the phrase is something that really is modeled on the human voice and on breath.

MATT: Oh, interesting.

MOSI SECRET: So, there is something that begins and there is something that ends. And one's breath and one's phrasing is highly personal and it is like – it is the signature. It is—the way you breathe, the way you speak is what makes your music musically yours.

ANNIE: Huh.

MATT: You know it's interesting, I haven't really ever considered the way in which my breath is intrinsically tied to my speech in the way that's distinct in some way.

MOSI SECRET: Yeah, yeah. It made me think about the way in which it defines me or in a way that was kind of a signature of mine. The way that I have a rhythm—there's a rhythm to the way that I speak, which is entirely my own. And there's a rhythm to the way that you speak that is entirely your own. And that—and that it might even be possible to recognize that rhythm absent the words that I'm uttering.

MATT: Mmmm.

ANNIE: Huh.

MOSI SECRET: That there's something—that there's a sound that we produce with our breath that is so kind of innately ours. That—yeah, it's almost like a fingerprint.

MATT: Right.

ANNIE: Huh.

MATT: Right. And then it becomes this really interesting tension of then how do you escape that, or how can you?

MOSI SECRET: And so circular breathing then becomes this way of, okay, if this is my limitation, who am I or what am I if I don't have that limitation, if I can kind of sustain my breath indefinitely?

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Wynton Marsalis: [playing trumpet]]

MATT: So this is the piece, Moto Perpetuo.

MOSI SECRET: Which was this violin solo known to be kind of one of the hardest passages of classical music.

MATT: And in the 1960s, Rafael Mendez came across it…

MOSI SECRET: And played it for trumpet.

MATT: This version is a version by Wynton Marsalis.

MOSI SECRET: And it's like four minutes of just like unbroken, very high tempo sound.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Wynton Marsalis: [playing trumpet]]

MATT: That's two minutes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Wynton Marsalis: [playing trumpet]]

MATT: Three minutes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Wynton Marsalis: [playing trumpet]]

MATT: And it just keeps going on and on and on and on…

ANNIE: And another…

MATT: And on.

ANNIE: And another.

MATT: And on.

ANNIE: And another.

MATT: And on.

ANNIE: And another.

MATT: And on.

ANNIE: And another.

MATT: And on.

MOSI SECRET: Indefinitely.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Wynton Marsalis: [playing trumpet]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: Say Ah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Unidentified Person: Ahh…]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: He's swung blows that will split your melon, blows that will split your melon, blows that will split your melon, melon. He's swung blows that will split your melon, blows that will split your melon, blows that will split your melon, melon. Mute it, do it, dispute it, shoot it and salute it. Don't understand the point, mute it, do it, dispute it, shoot it and salute it. Don't understand the point, mute it, do it.]

[laughter]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Black Thought: He's swung blows that will split your melon, blows that will split your melon, blows that will split your melon, melon. He swung blows...]

MATT: And on, and on, and on, and on, and on --

ANNIE: And another –

MATT: And on, and on, and on, and on, and on --

ANNIE: And another --

MATT: And on, and on, and on, and on, and on --

ANNIE: And another!

ROBERT KRULWICH: Annie?

ANNIE: Yes.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Matt?

MATT: Yes.

ROBERT KRULWICH: It's Robert again.

ANNIE: Robert Krulwich.

MATT: Former co-host.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I didn't die, I'm just lying here. Nothing to do this afternoon.

[Laughter]

ROBERT KRULWICH: I have a thought. Let's talk about breath.

[laughs]

ANNIE: So, we told Robert what we were up to with this breath show. And he came back to us with a tale of a time when the air was so different that the creatures who breathed it were literally transformed. Okay, so we're talking 300 million years ago or so.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Yeah. The world at that time was wet and warm and very swampy.

ANNIE: And covered in forests filled with very weird looking trees.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Skinny but very tall. Like pencils. With a little, like a chicken on top or something, like a little feather head sort of top.

[laughter]

ROBERT KRULWICH: And of course what a tree does, is it takes in CO2 and pumps out oxygen. So, there's oxygen flowing into the sky in great amounts because there's so many trees.

ANNIE: Today our atmosphere is 21 percent oxygen. But back then…

ROBERT KRULWICH: The amount of oxygen in the air is something like 31 or 32 percent. Something like that. That's an oxygen rich—that would be like going into one of those, you know, into a greenhouse. Where you feel that very pleasant sensation of just very clear, I dunno, heady air that you can feel in a greenhouse. That's—the whole world was like that at the time.

ANNIE: Oh, is that why a greenhouse feels like that?

ROBERT KRULWICH: Yeah!

ANNIE: I'd never thought of that!

ROBERT KRULWICH: Yeah. You're getting a little oxygen high --

ANNIE: Oh! Dang.

ROBERT KRULWICH: When you go into a greenhouse. It's a little bit like maybe wearing a terry cloth robe in a really nice Four Seasons hotel.

ANNIE: Oh yeah.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Air-wise. You get gorgeous air.

ANNIE: [laughs]

ROBERT KRULWICH: Luxury air.

ANNIE: Right.

ROBERT KRULWICH: You finally, you finally feel pampered. I guess, is what I imagine.

ANNIE: Oh. It's sort of nice to like, imagine squishing through that moist, warm forest, feeling like you're wearing a terry cloth robe at a hotel.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Yes. [laughs]

ANNIE: But now you may not want to be doing that because of what all this oxygen has done to the bugs.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Oh yeah. You see something very startling going on.

ANNIE: And really quick, to understand this startling thing, you have to know that, both back then and today, bugs don't have lungs.

ROBERT KRULWICH: No, they don't.

ANNIE: Instead...

ROBERT KRULWICH: They have these little holes all over them. Like a polka dot, kind of outside.

ANNIE: And they get the air, and thus the oxygen, into their bodies through these holes. So, breathing for a bug is...

ROBERT KRULWICH: The equivalent of opening a window. You just open your valve and you wait.

ANNIE: Air drifts into the holes and the oxygen in the air feeds the insects cells. Now, because the oxygen is sort of just drifting rather than traveling through veins, the cells closer to the surface, closer to the window, get more oxygen. And so, if there's not that much oxygen in the air, you have to make sure all your cells are really close to the surface. Meaning, you have to be little. But when oxygen levels were 30-something percent…

ROBERT KRULWICH: The chances of a hungry cell in your body getting a meal has just gone up. And if more cells can feed, then you can grow bigger.

ANNIE: And bigger, and bigger and bigger.

ROBERT KRULWICH: There's a spider from that period—which, you know, spiders are very leggy animals. But how about, a leg that's a foot and a half.

ANNIE: You just like pat them on the head as you pass them by.

ROBERT KRULWICH: There's a dragonfly that had a wingspan that's about two feet across --

MATT: Oh dear god.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Two—just think about that for a moment. That's like a seagull in the form of a dragonfly.

[Laughter]

ROBERT KRULWICH: So, that would be so weird.

ANNIE: Wow.

ROBERT KRULWICH: They have a millipede. There was one that was eight and a half feet long.

MATT: Oh my god.

ANNIE: Actually, it might have been more like seven feet long. But still.

ROBERT KRULWICH: It would be like a gigantic crocodile in the form of a millipede.

ANNIE: You could just lie on one and read a book as it like slithered along.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Yes, it could be a bus you take to the next side of the forest. Lie on its back.

ANNIE: [laughs] Yeah, exactly.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Yeah.

ANNIE: Hmm. I guess like, if you're a bug what's in the air totally defines you.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Hmm.

ANNIE: Or set your physical boundaries, right? Because there's so much more oxygen in the air. Um. Oh.

[Phone rings]

ROBERT KRULWICH: That's Rick Burns. Oh. Hey. I'm doing an interview but can I call you back later? Okay.

MATT: Some things never change.

[Laughter]

ROBERT KRULWICH: That's true. I've never figured out how—I've never remembered to turn off the phone when we go do these things.

[Laughter]

MATT: So, four years ago is actually when we thought about doing this episode. And the reason, the impetus for that was actually because of this small piece of tape that we heard: the sound of a breath.

ANNIE BROWN: Do you do anything else? Do you have like a hobby?

MATT: And that breath and that tape came to us from New York Times audio producer Annie Brown.

ANNIE BROWN: Yeah. This came about because I was applying for a job at the New York Times.

MATT: This is 2017.

ANNIE BROWN: And I got an assignment that I had to find a story that was about controlling an urge or an impulse that was surprising and gave you some kind of instructions on how to do it. And I really wanted to get this job and I found these two people who figured out that controlling the urge to breathe was largely psychological. That actually it's like, really not a physical thing.

MATT: So…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, ANNIE BROWN: Okay.]

MATT: The two people Annie found are these free divers who live in Canada.

ANNIE BROWN: They're just like the most famous trainers of breath holding.

MATT: And Annie flew out to Canada, spent a day training with them in their house and then went to her hotel pool.

ANNIE BROWN: The Comfort Inn on Vancouver Island.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: So…]

MATT: With her instructor, Kirk.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: We're just going to go through a briefing. So, really just to kind of get us comfortable...]

MATT: And so Annie is standing next to the pool.

ANNIE BROWN: I got on a hoodie sweatsuit.

MATT: This place reeks of chlorine.

ANNIE BROWN: And like, the air is so thick, you know? It's just that kind of—it's so familiar to me.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: Are you a swimmer?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, ANNIE BROWN: Yeah.]

ANNIE BROWN: Like that's how it feels on the pool deck, that's how it felt at that meet I went – you know, it's just that is a very familiar feeling.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: Okay, so let's find that depth. So…]

MATT: She gets into the pool.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: I would say standing, we want an out collar bone. Be about like that, right? Like a good depth. Yeah? Okay.]

ANNIE BROWN: So, I'm on the side of the pool, I am just trying to relax. And so, I'm like, [Exhale] doing my slow breaths to calm my heart rate down.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: Nice and relaxed.]

MATT: Now most people can hold their breath for a minute or two, but beyond that—what happens is carbon dioxide starts to build up in your body and your brain starts to panic. It will try and get you to inhale or exhale before it starts to shut down. And Annie was trying to hold her breath for over three minutes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: In 10 seconds.]

ANNIE BROWN: And then it's like, okay, time to take a big breath in.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: And five, four, three, two, one.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [Inhale]]

ANNIE BROWN: Drop my hands on the side of the pool and just let myself—fall into the water. So, I'm face down in the pool, like arms floating by my side. Just floating there. Like a piece of Jello, you're just jiggling in the water. I was like, this is amazing. And I felt good through a minute and half where I was like, tap for one minute. Give me a signal. I was still feeling pretty good. And I move my finger and I show him that I'm okay. And then…

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [Distorted noise]]

ANNIE BROWN: I get my first contraction. Your body starts to demand to breathe by contracting the diaphragm. So you start getting these convulsions in your belly, that feel like hiccups. It's like ugh-ugh-ugh. And it's like okay, okay. Keep relaxing. Stage by stage, like your shins, relax them. Your knees, relax them. Your thighs, relax them. And then [ugh-ugh-ugh-ugh.] They're coming more and more frequently. But also there's this voice, like, ‘You didn't get a good breath in, you're not going to make it, you're the worst at this.' And so, just go back to the toes and the ankles and the shins and the knees and the stomach and the arms and the shoulders and the mouth.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: Two minutes]

ANNIE BROWN: And then Kirk…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: I want you to go on a vacation.]

ANNIE BROWN: Talks me through packing for this vacation.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: You're gonna go to Europe. You're going to grab your luggage and you're going to pack everything you need to go to Paris. Paris for two weeks.]

ANNIE BROWN: And I was really doing it, where I was like okay my luggage is under the bed. I'm going to pull it out, I'm going to unzip it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: Slow and relaxed.]

ANNIE BROWN: I was like, okay, what do I—I don't know what to bring. Definitely going to bring that coat though. So, okay, I start getting my coat. I was really trying to pack this coat.

ANNIE BROWN: Okay, my luggage. Pull it out, unzipping it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, KIRK: Go…]

ANNIE BROWN: I don't know what shirt to pack. Okay.

ANNIE BROWN: I can't do this packing thing anymore. And then it was just like—you're just fighting.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, ANNIE BROWN: Eh, eh, eh!]

ANNIE BROWN: You're just holding on.

ANNIE BROWN: You're not going to make it. You're the worst at this. You are a fucking idiot.

ANNIE BROWN: You're so dumb. Why did you do this? You're so bad at everything you ever tried.

ANNIE BROWN: And then. I was like, oh Madeline. Like I saw her from above. Her head in the water. And then I was like, Oh my god. This – this – it's this.

MATT: So, Annie grew up with two sisters. The oldest was Madeline.

ANNIE BROWN: And she had epilepsy. And so, starting at like age 10 or 12, she started having seizures, sort of just randomly. You know, it would happen like, um, at a, like when something really exciting was happening. Like she'd be at like, um, a school dance or like she'd be at like the football game of the year.

MATT: And eventually she started taking medication to control the seizures.

ANNIE BROWN: But after you have seizures and like are like the kid who's like convulsing on the floor, like you just kind of can't get any less cool than that. So, she was just like the most unabashedly herself person in the world. Like we, we all shared a Toyota Camry in high school …

MATT: Oh, like that was the one car for the three girls to drive?

ANNIE BROWN: Yeah, for the three girls to drive. But she got a vanity license plate that said, ‘Mad Dog.'

[Laughter]

ANNIE: Wow.

ANNIE BROWN: And then she got a SpongeBob steering wheel cover.

MATT: But, the big thing Madeline did, actually all three of the girls did, is swim.