Jun 4, 2019

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

JAD ABUMRAD: I'm Jad Abumrad. This is Radiolab. A couple years ago we did a show about a crazy Cold War CIA operation, and a little trick that the CIA invented to say something without saying anything at all. And it just felt like this one sort of vibed with the moment, you know, with the Mueller Report coming out and all the redactions and intelligence and counterintelligence about Russia. I don't know, this story just kind of resonated with us again. Also sort of feels like a throw-back to an earlier, simpler time. So we're just gonna replay it this week.

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: And I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: And today on the podcast ...

JULIA BARTON: Hey Robert, can you scoot back a little bit from the mic?

JAD: We have a cloak and dagger maritime adventure and secrecy in truth from reporter Julia Barton.

JULIA: So Jeff, maybe first you could start off just by introducing yourself.

JULIA: Yeah, so the story for me begins with this guy.

JEFF LARSON: Yeah, my name is Jeff Larson. I'm the Data Editor at ProPublica.

JULIA: ProPublica's this investigative journalism outfit, and Jeff does a lot of their ...

JEFF LARSON: Data-based reporting.

JULIA: So in any case, it was summer of 2013. You know that big story about how the NSA had just been monitoring millions of Verizon customers?

JAD: Mm-hmm.

JULIA: That just came out. Jeff's watching the story like all of us are. And then the thought occurred to him, "Jeez, they're monitoring all of these people."

JEFF LARSON: Hey, does that include me?

JULIA: So he goes over to the NSA's website. He was surprised to find that right there on the site ...

JEFF LARSON: You could file a Privacy Act request for your metadata.

JULIA: They have a little online form right there.

JEFF LARSON: It's a service that they offer to everybody. And so I went ahead and did that.

ROBERT: And this is yourself you're requesting? You're saying what do you know—what do you know about who I called and who I heard from?

JEFF LARSON: Yes, exactly.

ROBERT: What were you expecting?

JEFF LARSON: The best case scenario would be just a—you know, a page of all of the communications actually to my wife. My wife's a Verizon customer and I'm an AT&T customer, so all my phone calls to my wife, I guess. I didn't think that I would ever get any response back.

JULIA: So then he hits submit, expecting nothing to happen.

JEFF LARSON: But it was actually really, really quick. I think it was on the order of 10 or 12 days. You know, it came to my home address, sort of a manila envelope. You know, my wife called me immediately when she picked up the mail and said, "Hey, you know, you got a letter from the National Security Agency." And there was complete panic in her voice.

ROBERT: So now she's just looking in the cabinets for small little beeping objects.

JEFF LARSON: Yeah, right. Exactly.

JULIA: And when he opened up the letter ...

JULIA: Could you read it?

JEFF LARSON: Yeah, I have actually have it up right now.

JULIA: The letter said, "We cannot acknowledge the existence or non-existence of such metadata or call detail records pertaining to the telephone numbers you provided."

JEFF LARSON: Exactly.

ROBERT: What does one know when one hears that response?

JEFF LARSON: I don't know. I mean, when you're a reporter and you hear that, it's sort of the—it puts you in this weird place.

JULIA: So Jeff takes the letter into work the next day, and he shows it to a colleague ...

JEFF LARSON: Who had been doing a lot of reporting on drone strikes and Guantanamo.

JULIA: And he's like, "What the hell is this? Does it mean something?"

JEFF LARSON: And she said that was a Glomar Response.

ROBERT: How do you spell—how do you say—how do you spell glomer or glomar?

JEFF LARSON: Glomar is G-L-O-M-A-R.

ROBERT: Glomar.

JULIA: What did you think just of the word?

JEFF LARSON: I thought it was—I thought it was some lawyer named Glomar who had argued—successfully argued the case, because it sounded like a bit of legalese. I didn't know the fascinating story behind it.

JULIA: So I started looking into it, and right away found this nutty story involving a nuke, a claw, a billionaire, some manganese, and this is classic tension between secrets being really necessary and really harmful.

JAD: Some manganese!

JULIA: But to get there, you have to start with this guy.

JULIA: Okay, let's just start out by getting your name and how we should identify you.

DAVID SHARP: Well, my name is David Sharp. That's my real name. If that's what you were wondering.

ROBERT: [laughs] This—this makes it all much more mysterious. What have been some of your other names?

DAVID SHARP: During the mission my name was David Shoals.

JULIA: So in the late '60s, David was working at the CIA. He'd been there for a while. And he got called onto this new thing called Project Azorian.

DAVID SHARP: Yes. I started the program in 1969.

JULIA: Here's what you need to know: In the late '60s, the US and the USSR were playing this high-stakes chess game with their nuclear submarines, cruising around international waters.

DAVID SHARP: There was a lot of harassment that went on.

JULIA: Inching on each other's territories. In fact, in January of 1968, a U.S. Naval ship was captured after leaving Japan, and everyone was worried that the Soviets had our code books.

DAVID SHARP: And there was an interest in getting even.

JULIA: Well, two months later in March of 1968, a Soviet sub called the K-129 just vanished. We don't know exactly why it sunk. There's all kinds of conspiracy theories about what might have happened. It just sank to the bottom of the ocean. And once the Soviets sent their search crews out trying to locate it and failed, we came in and somehow, through our sensor technology or whatever reason your conspiracy theory of choice might tell you, we found the boat. So then the thought was if we could get inside that thing, such a bonanza.

DAVID SHARP: There was a lot to be learned. Whether it would be the code books, the cryptographic equipment ...

JULIA: Or—and this is the big one ...

DAVID SHARP: The nuclear missiles.

JAD: It had—it had nuclear missiles on board?

JULIA: Yep.

DAVID SHARP: The Chief of Naval Operations, he really wanted to see if we couldn't recover that submarine. The whole thing.

JULIA: The problem was that the sub was three miles below the surface of the ocean, and the pressures at that depth according to David are roughly ...

DAVID SHARP: 7,500 pounds per square inch.

JULIA: Which meant to get the whole thing up, they were looking at scenarios where they'd have to lift something like ...

DAVID SHARP: 14 million pounds.

ROBERT: [laughs] Oh my God!

JULIA: Oh, that all. No big one.

JULIA: So their solution is to get a room full of top secret engineers together and just start spitballing ideas. Like, what if we just went down there and attached rockets to it?

DAVID SHARP: And pow! Blast the target up to the surface.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JULIA: Wait, how do we catch it when it comes back down? It's heavy. What if we—okay, we could—we could put these ...

DAVID SHARP: Pontoons or gas-filled bags and float the target up.

JULIA: Except that we can't get the gas in there because of the pressure.

ROBERT: Boy, these must have been amazing meetings where you could say anything.

DAVID SHARP: You could say that.

JULIA: So in the end they settled on a claw.

JAD: A claw?

JULIA: The idea was to build this gargantuan, eight-fingered claw and—and a boat, and then you would put the claw in the boat, bring it out on the high seas, and then you would lower the claw on a three-mile long piece of pipe string. And then like one of those carnival games, you know, where you have to grab the toy by remote control?

JAD: Yeah.

JULIA: You would position the claw over the submarine and exactly so, and then you would yank it off the bottom of the ocean, pull it back into the boat. Gates would open on the bottom of the boat and the claw and the submarine would come into a chamber and you would have it.

JAD: And you're not making any of this up?

JULIA: I am totally not making it up. The CIA made it up.

JAD: Because it just sounds weird.

JULIA: But they did it. They got the money, they got the approval from the president. But they still needed a cover story. So they called up ...

DAVID SHARP: Howard Hughes.

JAD: The billionaire?

JULIA: Yep, and they asked him—or probably his people, "Do you guys think you could just pretend to have this sudden interest in manganese mining from the bottom of the ocean?"

JAD: That was the cover story?

JULIA: Yes!

DAVID SHARP: Partly because Howard Hughes was a known inventor.

ROBERT: Wasn't Howard Hughes at this point living in isolation in Las Vegas, his fingernails growing inches long and being pretty bizarre?

DAVID SHARP: You know, I don't know if he was living in Las Vegas, but the rest of that I think is probably pretty accurate.

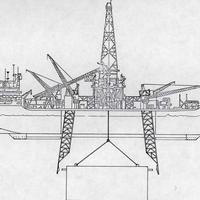

JULIA: Anyway, so they end up building this massive ship.

DAVID SHARP: The Hughes Glomar Explorer.

JAD: The ship was called Glomar? That's—that's where the word comes from?

JULIA: Yeah. It was built by this company called Global Marine. Global Marine. Glo Mar.

JAD: Oh!

JULIA: And in July of 1974, they get the boat out there, and they lower the claw. The claw descends three miles to the bottom of the ocean where the sub is, and the claw had lights and cameras on it so they could see what was happening.

JULIA: Do you remember when you first saw it?

DAVID SHARP: Yeah, I do. It was a very badly mangled hull, and we could see it very well.

JULIA: They actually could watch as the claw wrapped its massive claw hand around this sub and began to pull it back up. 14,000 feet, 12,000 feet ...

DAVID SHARP: About 9,000 feet from the surface, we were beginning to feel some cautious optimism that we might just pull this thing off after all.

JULIA: And then ...

DAVID SHARP: I felt just a little—a little bump in the ship, and we went to the control center, and everything looked normal on the television screens. But then it suddenly occurred to the operators that these television images had not been refreshed. In other words, they were television images taken maybe 15 minutes ago. And when they refreshed those images and got the real time picture of what was going on, it showed that we had lost. We'd lost most of the submarine.

JULIA: Basically, the part of the sub with the nukes, with the missiles, maybe with the codebooks, and all the stuff they wanted, that part broke off, and years of work, millions of dollars just slowly sank to the bottom of the ocean.

ROBERT: Did your heart go "Ugh?"

DAVID SHARP: Yeah. Yeah, it did. It was—it was intensely emotional.

JAD: And in the end, did they find anything?

JULIA: We still don't really know, because they've never actually disclosed what they found in that piece.

ROBERT: Huh.

JULIA: From David's description, it sounds like they didn't get a lot. But here's the whole reason I'm telling you this. It's because not long after that, like, intense moment of disappointment, the story starts to break in the press. Journalists are starting to call up the CIA, they're asking all these intense questions. They're onto it. And the CIA has to figure out what to say and what not to say.

DAVID SHARP: It's a dilemma. There's no question about that.

JULIA: Which brings us to Walt.

WALT LOGAN: Walt Logan.

JULIA: Which is, just to be clear, not your actual name.

WALT LOGAN: It's a pseudonym.

JULIA: Okay.

JULIA: So in 1975, Walt was a lawyer at the CIA.

WALT LOGAN: At that time, I was the Associate General Counsel.

JULIA: And as the story was breaking and all these journalists were asking questions, it became his job ...

WALT LOGAN: To develop the response. Simple.

JULIA: Except not so simple.

WALT LOGAN: [laughs] Yes. There's a diplomatic element of what's going on in here that isn't so obvious, and that is that you have the Soviet Union and the United States at odds.

DAVID SHARP: And the problem was that we didn't want the Soviets to know either what we had found out or what we hadn't found out.

JULIA: Either way would have been bad, says David Sharp.

DAVID SHARP: If we said that we didn't recover any information on Soviet missiles ...

JULIA: Which was the truth.

DAVID SHARP: Then that would tell the Soviets that they don't have to worry about the security regarding their warheads.

JULIA: David says we wanted them to worry. This is the Cold War. We might as well make them think we found something. On the other hand ...

DAVID SHARP: If we said that we did recover information on the missiles, but we're not gonna tell you, that would be lying.

JULIA: And they couldn't do that.

JAD: Wait. Don't governments lie all the time? Why couldn't they lie?

JULIA: Well, because this is 1974. This is the year of Watergate. This is the year that Congress rakes the entire federal security apparatus over the coals. This is also the year they revisit something called the Freedom of Information Act. FOIA. Actually, FOIA had been around for a while, but that's when FOIA finally got some teeth. The law says anybody, any American should be able to ask the government for documents and the government has to respond. It has to fork over that information.

WALT LOGAN: Well, let me put it this way.

JULIA: Walt's not a huge fan of this law.

WALT LOGAN: The Glomar was a tremendous investment of time and resources, and to willy-nilly give it over to somebody who writes a letter to the agency is—is preposterous.

JULIA: The way Walt sees it, the CIA's job is to keep secrets, and keeping secrets keeps America safe.

WALT LOGAN: Yes.

JULIA: In fact, every CIA employee is legally bound to protect something called ...

WALT LOGAN: Intelligence sources and methods.

JULIA: It's not an option, it's a law. Hence, his ...

WALT LOGAN: Dilemma.

JULIA: So there he was.

WALT LOGAN: Between a rock and a hard spot.

JULIA: Under the FOIA law, the public has a right to know. On the other hand, under Walt's oath, he has a legal obligation to not tell.

JAD: It's like the classic tension of our times.

JULIA: Exactly. Walt has to say something. He has to be truthful when he says it, but he also cannot reveal anything.

WALT LOGAN: That's correct.

JULIA: And people at the agency had been trying to figure this out for months. Which is why they brought in Walt.

JULIA: And how long did it take you to come up with this kind of response?

WALT LOGAN: I would say probably a half an hour.

JULIA: Wow!

JULIA: That half an hour of work has tortured journalists and lawyers for almost four decades. Here's what he came up with.

WALT LOGAN: The Glomar Response was basically the following: we can neither confirm nor deny the existence of the information requested but hypothetically, if such data were to exist, the subject matter would be classified and could not be disclosed. Very straightforward. Now think about that. That's—that addresses what we were—you were just trying to put your finger on. You can't confirm it.

JULIA: Which will be giving up secrets.

WALT LOGAN: Nor deny it.

JULIA: Which would be a lie.

WALT LOGAN: But if it was classified, it couldn't be revealed anyway.

JULIA: Suckers!

WALT LOGAN: [laughs]

JULIA: As you can imagine, people who filed these FOIA requests, when they got a response like that, they were like, "That's not gonna stand. You are the sucker." They fought it in court, and the fight went on for years, knock-down drag-out, but eventually the government wins.

JAD: The judge ruled in their favor?

JULIA: Well, the judge agreed to their logic, that sometimes revealing even the existence of documents endangers national security. And to make a long story short, use of this kind of response exploded to the point where now you hear actors like Will Smith using it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Will Smith: I can neither confirm nor deny.]

JULIA: You hear Pixar characters using it. Hollywood publicists.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: I can neither confirm nor deny the rumors.]

JULIA: Ex-Congressman Anthony Weiner.

[NEWS CLIP: Congressman Anthony Weiner told John Colin that he could neither confirm nor deny that the photo was him.]

JULIA: It's become this total boilerplate phrase of our time.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Conan O'Brien: I'm gonna ask you guys directly if you had personal experience with Viagra, have you ...?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Zac Efron: Can't confirm or deny that.]

JULIA: That was Zac Efron on Conan. But—but on a much more serious note, since that initial Glomar Response in 1975, more and more government agencies have begun to use it.

DAVID SHARP: Surprisingly.

JULIA: And not the obvious ones. We found some from the Department of Commerce, Department of the Treasury, Department of Energy.

DAVID SHARP: It makes you wonder how they got along before then.

JULIA: Centers for Disease Control.

WALT LOGAN: I was amazed that this thing has legs.

JULIA: And it makes you wonder, why does this thing have legs? Why now?

JAD: Yeah, it is weird. Like, that guy, that ProPublica guy you—you started with.

JULIA: Jeff Larson.

JAD: Yeah, that guy. If all he's asking is what do you know about who I call, and the only answer he's expecting to get is like, "We know you call your wife." Why would they Glomar that?

JULIA: Well, they told him in that letter that if they confirm or deny the existence or non-existence of those records ...

JEFF LARSON: It would help our—the adversaries of the United States.

JULIA: [laughs]

ROBERT: And just—just so that I can empathize with the United States of America for a moment, why would that be right? Like, if they said you called your wife on Monday at three o'clock, Thursday at 4:30. She called you back at 6:15. What would an enemy then learn, do you suppose?

JEFF LARSON: I guess that they—they would learn that they have records of me calling my wife.

JULIA: So the statutory reason why I've read that your sort of FOIAs are denied with a Glomar Request is that, if you say someone is under surveillance by acknowledging records, or you say they're not under surveillance by acknowledging no records, either way it outlines the contour of the program. It's a tiny crack through which people can sort of puncture the wall and get information about the larger program.

ROBERT: There you go! You've just given us the government's position. That makes perfect sense to me. I mean look, if a thief were to come up and say to me—I'm a cop. "Are you investigating me?" If I say yes, then he can hide. If I say no, then he will go rob another bank.

JULIA: Right.

ROBERT: Or the other robbers will know that I missed a really good bank robber and I'm terrible at it. In any way, I seem like—I feel suddenly dangerously exposed.

JEFF LARSON: I don't know. It's all very, very confusing. And you could wrap your brain around it and never get to sleep for the rest of your life if you thought about it really hard.

JAD: And by the way, there is a—we should say—a very good argument against that argument from the government.

DINA TEMPLE-RASTON: That transparency is a good thing. If you have an agency that doesn't have any sort of constraints on it, or doesn't have the proper oversight, it oversteps.

JAD: That argument from NPR special correspondent Dina Temple-Raston when we come back from the break.

[JOSH: Hi, my name is Josh and I'm calling from Harlem, New York. Radiolab supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org. Thanks.]

JAD: I'm Jad Abumrad. This is Radiolab. Okay, we're back with our story from Julia Barton about the Glomar Response, where government agencies refuse to either confirm or deny something in response to a freedom of information request. And as Julia was reporting this piece, Robert and I called up NPR special correspondent Dina Temple-Raston just to sound her out, because she covered counter-terrorism for NPR for years, and so she'd been Glomared on drones. She's been Glomared on terrorism investigations.

DINA TEMPLE-RASTON: I've never actually heard it as being Glomared, I have to say.

JAD: And she told us something interesting: that this whole non-denial/denial state of weirdness has created some very unique situations for her as a reporter. Like, say on any given Monday, she sits down, writes a FOIA request about the drone program, which will get Glomared. Then on Tuesday, the government will turn around, organize a meeting for reporters about the drone program.

DINA TEMPLE-RASTON: Let's say a story about a drone target is out, and it seems incorrect to the White House. And in a big enough way that they feel they need to correct the record. So they will often conduct a conference call on background with a number of reporters from a number of different organizations, and basically say to those reporters, "Okay, here are the following people who are talking to you, but you are not allowed to say who they are. And they're gonna put this in context for you. And you can quote them as --" and they usually set the ground rules, you know, senior administration official or administration official familiar with the program, or something like that. And what then happens is they get to correct the record without officially confirming that something is going on. I mean, there's an interesting thing about the White House and government, that—that they believe that they still have deniability if a high-ranking official who is unnamed says something is going on. And as soon as a name is attached to that, then the information in their view fundamentally changes. It suddenly becomes concrete.

JULIA: And actually that's kind of what happened with the Project Azorian, that Glomar mission from the '70s. Even now, the only reason that we know half of what we know about this whole thing is because some historians were really dogged with their FOIA requests, and they found out about this whole series of internal CIA newsletters. And in one of those newsletters, there was a—an article with a title that clued them in that this was about the Glomar mission. They FOIAed that specific article.

JAD: Oh, and that's what ultimately sprung it loose?

JULIA: Yeah. When they have a name of an article, then they can FOIA that. And then it's really hard for them to say no documents exist because they have the actual title of it.

JAD: I see, so when it gets specific.

JULIA: Yes. So the CIA released this article but I mean, by now decades have passed. And that's what people now say about the Glomar Response, is that it's just a delaying tactic.

JAMEEL JAFFER: Because Congress in 2000 ...

JULIA: I talked to this one guy, Jameel Jaffer. He's the deputy legal director of the ACLU, and they get Glomared all the time.

JAMEEL JAFFER: We've come to expect them now, unfortunately.

JULIA: He says, you know, I mean when they get a Glomar they don't get upset. They just think, "Okay. Well, we've got another two years in court."

JAMEEL JAFFER: That's what it means. It means—it means you have two years of litigation before you even get to the point of arguing over whether the government has a right to withhold the information.

JAD: What's happening over those two years?

JULIA: Well, they're trying to strategize. So if they really want to know about a program and they really want to get those documents, they will look for any sort of mention of those documents by public officials in the same agency.

JAD: Hmm.

JULIA: So say you have a pen.

JAD: Mm-hmm.

JULIA: And you love this pen.

JAD: Mm-hmm.

JULIA: But you don't want anyone to know about it. Someone asks you if it exists and you say, "Hell, no."

JAD: Can't confirm or deny.

JULIA: Right. And then you're at a party and you just mention it in passing. You can't help yourself.

JAD: Love this pen. You should check out this pen.

JULIA: Right. Well, I was nearby. Now I take it to a judge and I say look, "He's talking about this pen at a party. He's bragging about it. He can't refuse to confirm or deny its existence anymore.

JAD: So they're looking for cracks in the Glomar.

JULIA: Yeah.

JAD: Over those two years.

JULIA: Yeah. And it's this really expensive legal strategy that most people can't even get to. Only big outfits like the ACLU can even challenge them.

JAMEEL JAFFER: And the government may ultimately lose in all of these cases, but it will lose at a time when the public debate will have moved on to something else.

JULIA: And that's one of the real dangers here, he says. It's that, by the time the truth finally comes out, we don't actually care anymore. It's ancient history. But not for everyone.

DAVID SHARP: Well, the divers who were specially trained ...

JULIA: Going back to that Glomar mission, the original Glomar mission for second. David Sharp says after they were able to pull that last fragment of the sub out of the water, they were able ultimately to look inside.

JULIA: And were there people in there?

DAVID SHARP: There were. There were—there were three crew members that were basically whole and recognizable. And there were major parts of another three crew members. But they were—they were given the full—full respect that I think the Soviet navy would have conferred upon their own people under those conditions.

JULIA: The problem was we were keeping the whole thing secret, and that allowed the Soviet government to do the same thing. They probably didn't want the embarrassment of acknowledging that they'd lost this really important submarine. They also didn't want to derail arms talks that we were having with them. And for a bunch of other reasons, they just pretended it never happened. But they had to say something to the families of the sailors who died on that submarine.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: [speaking Russian]]

JULIA: Here's the widow of the second-in-command on the K-129. Her name is Irina Zhuravina. And a while ago, she was interviewed on Russian television. She's showing the death certificate for her husband, and then she reads it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: [speaking Russian]]

JULIA: I'll translate it as best as I can. "Death certificate. Cause of death: presumed dead."

JAD: What?

JULIA: "This horrible, inhumane death certificate. I don't know who is the author. I've wanted to know for 30 years. Who is the author of this horrible, inhumane document? This is what we've been living with for 30 years."

JAD: They wrote cause of death: presumed dead on the death certificate?

JULIA: Yeah.

JAD: Doesn't even make any sense.

JULIA: And that—that's cruel.

JAD: Yeah.

JULIA: In this context, it's cruelty. That's what she's saying. Giving an answer that says nothing can be worse than just silence.

JAD: Big thanks to reporter Julia Barton. There is much more Glomar information on our website, Radiolab.org.

[SAMMY: This is Sammy from Miami. Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is produced by Soren Wheeler. Dylan Keefe is our Director of Sound Design. Suzie Lechtenberg is our Executive Producer. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Becca Bressler, Rachael Cusick, David Gebel, Bethel Habte, Tracie Hunte, Matt Kielty, Robert Krulwich, Annie McEwen, Latif Nasser, Malissa O'Donnell, Sarah Qari, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster. With help from Shima Oliaee, Audrey Quinn and Neil Danesha. Our fact-checker is Michelle Harris.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.