Jul 12, 2016

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert Krulwich.

MOLLY WEBSTER: I'm Molly Webster.

ROBERT: This is Radiolab. And today ...

MOLLY: Today we've got a guy asking a pretty common question.

ROBERT: Yeah, but the way he tries to solve this question is at first a thrill to him.

MOLLY: Mm-hmm.

ROBERT: Then a crutch, then a curse and then it ends up in an extraordinarily deep puzzle.

MOLLY: It comes to us from producer Andy Mills.

ANDY MILLS: Our story is about David Weinberg, a buddy of mine. And it starts off right around the time he gets out of high school.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah, I graduated from high school in 2000 and then went directly to university and then I got kicked out somewhere at the beginning of the second semester. And then left the town that I was living in and moved to the town where all my friends were going to college and ...

ANDY MILLS: He moves into, like, a group house.

DAVID WEINBERG: It was a party house.

ANDY: Him and a bunch of his friends.

DAVID WEINBERG: There was a giant cross in the front yard that my friends had found while tripping on acid and put in a shopping cart and they put it in the front yard.

ANDY: Our fact-checker actually found that they were tripping on mushrooms, not acid, but anyway ...

DAVID WEINBERG: A lot of drinking, a lot of partying.

ANDY: And for David, for a while, it was good.

DAVID WEINBERG: I'm hanging out with, like, the people that I care about most in the world. I feel incredibly free. And then I—it just started to get old.

ANDY: For one, every day when his friends would go off to class, David would have to go to work.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah. During the day, I was working as a janitor at the university where my friends went, and during the evenings I would deliver pizzas.

ANDY: And it went on like this for years. You know, day after day, they would party but then in the morning when his friends would go to class, he would go and clean toilets. And then deliver pizzas. All through sophomore year, they would go to class, he would clean toilets and then deliver pizzas. Junior year, class, toilets, pizzas.

DAVID WEINBERG: And, like, I think there was this rage that started to build up inside. I mean, I was really sick of cleaning the toilets of kids in the dorms who I resent but who I also recognize are able to do something that I wasn't able to do. And, you know, all my friends were at that university and they were about to graduate. And so I think I was also worried that, like, well, they're all gonna go off and live these lives and I'm gonna be stuck here cleaning toilets.

DAVID WEINBERG: And, like, I think there was this rage that started to build up inside. I mean, I was really sick of cleaning the toilets of kids in the dorms who I resent but who I also recognized are able to do something that I wasn't able to do.

ANDY: And on top of that, by the time that most of David's friends were seniors, he was spending his weekends in jail for driving on a suspended license.

DAVID WEINBERG: So my life at that point was like cleaning toilets in the morning, delivering pizzas in the evening and then every weekend I was in jail. And there was kind of this breaking point. The one thing—one thing that we did a lot of—like, we listened to a lot of punk music. My friends were in punk bands. And we would just, like, get really drunk and, like, yell into the speakers. Probably like three or four nights a week. [laughs] You know? And one night, we were doing that. It was me, my friend Danny and my friend Mark, and something just snapped inside me. I just kinda lost it. Just started, like, grabbing chairs and hurling them through windows and just, like, smashed out all the windows in our house. You couldn't see the floor because there was, like, wreckage everywhere. And I was all bloody. It was intense. It was—I don't think it hit me until the next morning when I saw what it looked like. Like a hurricane had ripped through the house.

ANDY: Yeah.

ANDY: And all of his friends ...

DAVID WEINBERG: Everyone was just sort of stunned.

ANDY: They were sort of like, "What's going on?"

DAVID WEINBERG: And then—you know, when you confront a reality like that, everything just sort of gets stripped away and you're just left with this question that's like, "Who am I and what am I doing with my life?"

ANDY: And around that time, David was driving around delivering pizzas, listening to the radio, and ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, This American Life: WBEZ Chicago, it's This American Life. I'm Ira Glass.]

ANDY: ... heard this story.

DAVID WEINBERG: This Scott Carrier story called "The Test."

ANDY: Oh yeah.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, This American Life: I was hired to interview men and women in the state of Utah who received Medicaid support for a treatment of mental illnesses, generally diagnosed as…]

DAVID WEINBERG: And it just, like, stopped me in my tracks.

ANDY: Alright so the story is by a guy named Scott Carrier, he's a frequent contributor at This American Life. And it's basically about how he gets this new job.

DAVID WEINBERG: He gets this job driving around the state of Utah interviewing schizophrenic people, giving them this test.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, This American Life: I took the job because I had no other. I took the job because I had just quit my steady job, my professional job.]

ANDY: And this is happening at a point where Scott's life is falling apart.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, This American Life: What I wanted more than anything was to put my boss on the floor and stand on his throat and watch him gag.]

DAVID WEINBERG: He talks about how he hates his boss.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, This American Life: Then my wife moved out, took the kids and everything.]

DAVID WEINBERG: His wife had just left him.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, This American Life: So I took the job and did the job, and my life will never be the same.]

ANDY: And David says as soon as he heard that story ...

DAVID WEINBERG: I remember thinking, like, "I need to figure out how to become a radio producer." That's what I need to do.

MOLLY: [laughs] Why?

ROBERT: Why does he want to become a radio producer?

ANDY: Well, I think first off, Scott Carrier is really good at what he does.

ROBERT: Yes.

ANDY: There's something about him that is magnetic, right? He gets people thinking, "I want to do that." But maybe more importantly, in this story, Scott is stuck. Not too dissimilar from where David finds himself. And what Scott does is he turns his stuckness into a story. And in doing so, kind of gives it meaning.

ROBERT: It's rising above your situation, sort of.

ANDY: Yeah.

ROBERT: Yeah.

ANDY: And when David hears it he thinks, like, "Well maybe I can do that too."

ROBERT: I see.

MOLLY: Makes sense.

ROBERT: Yeah.

DAVID WEINBERG: It was like, okay, this is my ticket.

ANDY: So that summer he lined up a job at this camp.

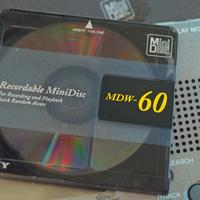

DAVID WEINBERG: This summer camp in upstate New York. And I bought this minidisc recorder.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Recording.]

ANDY: Got himself a mic.

DAVID WEINBERG: The little mic that you could clip onto your shirt.

ANDY: And ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Recording inside the tent.]

ANDY: He and his buddy Mark, who had just graduated, they left Colorado and headed to upstate New York.

DAVID WEINBERG: My idea was like, okay, I'll just go around and get all these recordings and then I'll write these story about what it all means and ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Day one.]

DAVID WEINBERG: Sort of like On the Road but with recordings.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: On the line, on the line.]

DAVID WEINBERG: We recorded the kids at the camp.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: You want to step out?]

ANDY: This bar fight when he was out with the other counselors.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: What's going on over there, is there a keyboard or something?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Yeah, we brought the keyboard. It's awesome.]

ANDY: He and Mark flirting with girls.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: What have you got these out for, buddy?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Listen, this is the coolest thing in the world. Put these on.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: All right.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Isn't that cool?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: Yeah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: It's a live recording of what's happening right now.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: Right now?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Yeah.]

DAVID WEINBERG: I distinctly remember just being in complete awe of hearing recordings that I had made where nothing's happening.

MOLLY: [laughs]

DAVID WEINBERG: The idea that I could make a recording and listen to it, it was like ...

ANDY: Like early man sees a mirror, you know, and just can't stop staring at it.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah.

ANDY: He actually wasn't interviewing people or anything like that. He sort of decided that he wanted to record moments as they happened to him. And he figured the best way to do that was to record secretly.

DAVID WEINBERG: I had cut a small hole in all of the pants and shorts that I had in the pocket. So I could get up in the morning, put the minidisc recorder in my pocket, and then I'd run the cord down my shirt. And any time something interesting was happening, I would slip my finger in my pocket and just press the record button.

ANDY: At first just some moments here and there.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: You look really scary.]

ANDY: These possible scenes for a story maybe.

[ARCHIVE CLIP Abraham.]

ANDY: Then ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: We gotta get on the 7 train.]

ANDY: He and his buddy Mark moved to New York City.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: I still remember ...]

ANDY: Now everything sounds interesting.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, protester: The system must be overthrown!]

ANDY: So he's recording more and more.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Monday, upper middle east side.]

ANDY: Then every day.

ANDY: After New York, he and Mark hitchhiked across Europe together.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mark: My name's Mark.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: And I'm David.]

ANDY: And at this point, David is recording people who pick him up.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, driver: What are you doing in Europe?]

ANDY: He and Mark and their other buddy, Tom, on the side of the road.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: When the rhythm of the cars on the highway is even, it's solid, it's almost like waves on the ocean.]

DAVID WEINBERG: You know, every street performer, I would run up to, stand next to and record.

ANDY: Just everything.

ANDY: And you're still thinking to yourself, "Man, I'm just getting gold."

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah! I'm just like, you know, this the raw material for my first great story, you know? I think I tried—I separated myself from—it's kinda cliché, like,"Oh yeah, you graduated from college and you backpack around Europe." And it's like, "No, no, no. I'm not one of those people. Like, I'm actually making a grand documentary. I'm a somebody. I'm not just like everybody else."

ANDY: Yeah.

ANDY: Meanwhile, David is accumulating hundreds and hundreds of hours of tape. And one thing that you'll hear if you manage to listen through all of it is just him hanging out with his buddy Mark.

DAVID WEINBERG: He was just one of those people, we became instant friends the moment we met.

ANDY: Mark was a year older than David. He was really into music, sound engineering.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [singing]]

DAVID WEINBERG: We had this perfect dynamic where Mark had, like, enough talent. Like, he could actually play music and, like, riff these funny songs on the spot.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [singing]]

DAVID WEINBERG: And I sort of brought the raw enthusiasm to it.

ANDY: [laughs]

ANDY: And the two of them, together ...

DAVID WEINBERG: We would just end up in these crazy places.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [singing] "Walkin' on Sunshine"]

DAVID WEINBERG: Oh yeah.

ANDY: Do you remember this recording?

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah, I remember it. We were in Croatia, and we ended up at this huge, amazing party. It was like in this old, abandoned, cavernous building with just hundreds of beautiful Croatian people.

DAVID WEINBERG: That was such a great day.

ANDY: But then ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Do you want French fries, veggies or apple sauce?]

ANDY: ... Dave and Mark went back to the States. Mark went over to Seattle to record an album with his band and David ...

DAVID WEINBERG: I got a job waiting tables at an Applebee's.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: You guys want any dinner salads or soup before the meal?]

ANDY: Back in his hometown. Living in his parents' basement.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, manager: And if you guys aren't taking two seconds to try to upsell, you're taking money out of your pocket. And if you're taking money out of your pocket you're taking money out of mine.]

DAVID WEINBERG: This kid that I hung out with the most that I worked with was this meth addict. I would go over to his place after work and, like, drink beer and play video games and he would get high. And it was like really depressing. It was a hard time. It was shitty.

ANDY: And David has all of this tape. Like tons and tons and tons of tape from times with Mark in New York, in Europe. But he has no idea what to do with it. So he just keeps hitting record.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, manager: Weinberg.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Yes.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, manager: Set up for the night shift.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: All right.]

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah, I mean, I just—I just needed that more. I think I needed the recording and the wire more than anytime in my life. Like, that was the period when I needed the wire the most because it was ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Raspberry lemonade? Sure. Sure.]

DAVID WEINBERG: ... this sucks but, like, I'm gonna get through this and this will be a chapter in the story. I spent a lot of my time with my finger gently resting on the minidisc player. I could feel the discs spinning when it was recording. It was just very satisfying, comforting, you know?

ANDY: Like a pulse, in a way.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah, yeah.

ANDY: Like it's still going.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Excuse me. Excuse me? You know what we should get? One of those bells? Bing!]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: Ding ding ding ding ding ding!]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Or really, just if they just make a speaker. Like, ding! And then it just keeps getting louder and louder 'til you make the drink.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, woman: I put drinks before everything else.]

ROBERT: Does he have a story? I'm not so sure he's got one to tell.

ANDY: Right. Well, hang on.

ROBERT: Okay.

ANDY: And after the break, I think you'll—I think you'll hear an answer.

ROBERT: Okay.

[LISTENER: This is Neva Bartram from Encinitas, California. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org.]

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

MOLLY: I'm Molly Webster.

ROBERT: And we're back.

MOLLY: And today we're in the middle of the story about David Weinberg, who is recording almost every day of his life. And last we left him, he was in Applebee's working as a waiter and living in his parents' basement.

ANDY: Right. But he did eventually save up enough money to travel again. Went to Alaska, things like that. And he says that well, when times were bad, like at Applebee's, he needed these recordings to make his life feel like it had, like, meaning. When times were good, he couldn't stop recording because he was worried that he was gonna miss something.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah, occasionally like something would go wrong. Like I lost three or four recorders. They broke down over the course of the years that I was recording. And whenever a recorder broke, there would be a period where I'd have to wait for the new recorder to come.

ANDY: Uh-huh.

DAVID WEINBERG: And I just felt like on edge all the time. In this weird twisted way, like, I felt like I was missing out on life because I wasn't recording it.

ANDY: So when you would get the recorder it would be like a relief?

DAVID WEINBERG: Oh yeah, I'd be like, "Oh thank God! I can–" like, you know, this pressure would be released and I could go back to recording. And I would just feel like myself again, you know?

ANDY: But then ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Hey, is Brian ahead of you or behind you?]

ANDY: David ended up down in Seattle where he met back up with Mark.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah. And Mark and I got in some big arguments in Seattle before I left.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mark: Something that you said that was private.]

DAVID WEINBERG: He just told me one night at the bar, "I just hate the fact that you record me all the time." And, you know, I was recording that conversation too.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: I want to get to the heart of this.]

DAVID WEINBERG: And he just laid it all out for me. You know, like, he was someone who spent his day, all day, in a recording studio, meticulously laying down perfect tracks. You know, that was his life. And so to him, the idea that you would sort of like, record everything, it was wrong for a lot of reasons. One of which was just that he didn't think the experiences warranted that. And then he had, like, philosophical objections to it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mark: When I live my life, I live it like it's fleeting, everything is ephemeral.]

DAVID WEINBERG: That, like, what makes life great and worth living is that it is this fleeting thing and it's temporary.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mark: I like my life being temporary. I don't want—posterity is only good in certain doses.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: All right.]

DAVID WEINBERG: And when you are trying to constantly record it and capture it, you're just taking away from that aspect of life.

MOLLY: It's like don't keep trying to capture the essence of this thing, just be in the essence of the thing.

ANDY: Right, so here you've got David saying that, you know, he's recording all the time so as not to miss anything. And Mark is saying, "No, by recording all the time you are missing everything."

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah.

ANDY: You're missing the important things.

DAVID WEINBERG: And it got to the point that he said that he didn't want to be recorded anymore. And it was, like, really getting in the way of our friendship because it puts a ceiling on where your relationship can go when someone feels like they can't open up to you in that way. It just puts this wedge in between you in a way that's just awful.

ANDY: Did you stop recording at this point, or ...?

DAVID WEINBERG: Well, I couldn't stop. Like, at that point I just like, I don't know whether it's OCD or whatever it was, like, I couldn't stop recording, and so I was always recording. And the recording was like, almost like a uniform for this person that I wanted to be. It's like you're in a play and you think you're living this life and then when the disc stops, suddenly, like, the lights go up and you realize it's all fake. Just like, face it, dude. Like, you're just drifting.

ANDY: At this point, David has around 2,000 hours of tape. Because he keeps on recording, he's not really hanging out with Mark anymore. And he ends up drifting down to New Orleans. And this is not very long after Hurricane Katrina.

DAVID WEINBERG: And it's like, you know—like, you know, everyone has a story about the flood and it was like—you know, so I would, like, listen to these peoples' harrowing journeys. And then, like, all these injustices that they'd faced.

ANDY: So he decided to do something that he'd never really done before and started interviewing people.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, man: Yeah I've been here since the start, but I've been living in New Orleans East.]

ANDY: Telling their stories.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: How has it changed since then?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, man: Changed that much since Katrina?]

ANDY: With their permission, not recording them secretly.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, man: This store here opened up, you know?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: So where were you doing your grocery shopping before?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, man: I was doing it down in ...]

ANDY: And then he started getting those stories onto New Orleans Public Radio stations.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: You're listening to WWOZ Street Talk. Stories of New Orleans' cultural rebuilding.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: I'm telling you man, I appreciate that discipline. Man, I was growing up—I was growing up just terrible, man.]

ANDY: And then at night, he'd go home and he would listen to audio from the wire.

DAVID WEINBERG: Tape of like me in some bar, and ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: I think I offended everyone in that bar.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, man: Yeah, you—yeah, you didn't make that many friends there.]

DAVID WEINBERG: Like super drunk, and it's like ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: I called them all assholes.

DAVID WEINBERG: Like, what? Why did I think this mattered? Like, why, you know? And then also this, like, dynamic started to change in my mind, where, like, it's one thing to record your own life—and then yes, to be fair I was also recording other people but it was always framed around me and everyone else was just supporting characters. But then when I started doing stories in New Orleans, it was like, this is not about me, this is about other people and, like, suddenly it did start to feel dirty to record people. And it was like all of that sort of came to a head and I just felt worse and worse about recording, and then I just stopped. I was just like, "I don't wanna do this anymore."

ANDY: Well, what about that feeling you were talking about just moments ago, where without the recorder recording what's happening, you felt as if you were missing out? That an experience was kind of wasted because you hadn't gotten a chance to record it?

DAVID WEINBERG: I mean, that didn't go away. That definitely didn't go away. I mean, I feel like that still to this day. I sometimes feel like, "Man, I wish I was recording this!" You know? But it just forced me to really think hard about what moments in life were worth capturing and what weren't.

ANDY: You know, so, like, if you do try to capture a moment, then you're kind of out of that moment. But if you don't, then poof, it's gone.

MOLLY: Well it has the potential to be lost.

ANDY: Right, I think that we all can relate to this idea. But for David, the crux of that ...

MOLLY: Tension.

ANDY: To do it or not, like, that became really difficult for him, in part because of what happened next. A few months after he had quit recording, he was talking to Mark who, you know, is still back in Seattle, is very happy to hear that David wasn't recording anymore. And so Mark decided to go down to New Orleans and visit David and their buddy Danny, who lived down there too.

DAVID WEINBERG: And this is—man, this is hard because I haven't really told the real story about what happened with Mark. I'm trying to think. I'll tell you the real story and ...

ANDY: Yeah, just shoot.

DAVID WEINBERG: The—so Dan—Danny and Mark and I were really close, the three of us. And one thing we would do a couple times a year, we would all go up to the mountains together and just have this great trip together as friends. And so we were gonna do that in New Orleans, and so we got on our bikes and we rode down to the river and sat along the river for a while. And then we took the ferry over to the west bank, the other side of the river. You know, like, New Orleans is, like, glittering across the water.

ANDY: Got stoned.

DAVID WEINBERG: And it was just magical. And like—we were sitting there for a long time, just talking, like, having one of those deep philosophical conversations.

ANDY: David, for the first time in a long time, was not recording, wasn't worried about capturing the moment, so ...

DAVID WEINBERG: My mind was free to not think about the recording, you know? And then I was actually more present in some way, you know? And it just felt like it always did when we were close back in the mountains in Colorado. You know, it was like a great moment. And it just felt like it always did when we were close. And I wanted to keep hanging out there and Mark was getting kinda antsy. He wanted to go explore the city. You know, he wanted to go exploring. And I was just like, didn't really feel like it. I just sort of didn't want to be around other people. I was happy to be there with them. And then Mark just jumped up and took off, like just sprinted away. And we were like, "Whoa, that was weird." It feels very strange.

ANDY: David says that Mark said something in that moment but he can't, like, remember exactly what.

DAVID WEINBERG: And so we got on our bikes and we were only, like, only maybe a hundred yards, two hundred yards from the ferry that was parked there. And by the time we got to the bridge that connects the land to the ferry, I saw that Mark's bike was laying on its side on the ramp. I was just like, "Well, that's weird." You know, in my mind—when I think back about it, I feel like things happened very slowly. Why is Mark's bike laying down? Why are all those people shouting? They're looking into the river. Why are they looking into the river? And I look into the river and there's Mark. And he's swimming in the Mississippi and he's shouting something and I can't figure out what he's saying. And I was just like, "Holy shit." Like, this is really bad. And then I got really, really scared and I looked at Danny and Danny looked totally terrified. And he started to—you know, he was going down river obviously, it's a river, so there was a point I could see off in the distance. There was a boat, like a rescue boat had gotten into the water and Mark started to drift around the bend and he disappeared out of view.

ANDY: David and Danny, they kinda walk up and down the river looking for Mark. They couldn't find him. Then it gets dark, and Danny and Mark, they just head home and wait for news there. The next morning, still no news. A few days later, the authorities, they gave up their official search for Mark and assumed that he was dead. And a week or so later, they found his body.

DAVID WEINBERG: He had drowned.

ANDY: And I should just add that there is no reason to suspect that this was a suicide.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah.

ANDY: I'm sorry that Mark passed, man. That's—that's a tough story to hear.

DAVID WEINBERG: Yeah. Yeah.

ANDY: Let me ask you this. Thinking about this through the lens of, like, you being someone who has a compulsion, an obsession that is now under control but still lives in you, is there a part of you that wishes that you had been recording that day?

DAVID WEINBERG: Um, I don't know.

ANDY: The thing is, David says, not long after Mark had died, he started going through a lot of his old recordings. And sometimes he would hear on them these great moments between the two of them. But a lot of times, he says that almost like, he could hear that ceiling that those recordings had put on his friendship with Mark.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Man I wanna fucking take a boat down the coast so bad.]

[RECORDING, MARK: Yeah, nothing I wanna do more.]

DAVID WEINBERG: I was acting different than I would have if I hadn't been recording.

ANDY: Hmm.

DAVID WEINBERG: You know? Like, I was conscious that I was on tape all the time.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Mark: Even if the boat, even if you know ...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Weinberg: Danny was saying he was willing to, like ...]

DAVID WEINBERG: And I also hear myself in these recordings often stepping over him. Like, he'll say something and then I'll jump in and just like, clearly I'm just like—I'm on my own train of thought and I'm not really listening to him. And that bothers me a lot. I'm glad I don't have—I think I'm glad that I—I don't know. It's just so hard, because on the one hand I'm very glad that I don't have to live with that tape and that it doesn't exist.

ANDY: But at the same time, David says ...

DAVID WEINBERG: I feel like maybe I missed something. And maybe there's some part of what happened that night that I can't—that I missed! All I know is that he just said, "Let's get out of here," and, like, jumped up. I don't even remember exactly how he put it. I just remember that all of a sudden he was gone. If I had that recording maybe I could make sense of it and maybe something would be more clear about it. I think about that a lot. But then I also think what would Mark have wanted? And, you know, what—that probably trumps whatever clarity—I don't know. Yeah. But I still think about it a lot. I still think about what I would get from those recordings if I had them. And yeah. And I don't.

MOLLY: A big thank you to David Weinberg for opening up his audio archive and sharing it all with us and sharing this story.

ROBERT: And thank you, Andy Mills, who produced the whole thing.

ANDY: And listened to all of those hours of tape.

ROBERT: [laughs]

MOLLY: [laughs]

ANDY: I should add here, a little update on David, he's actually a producer at KCRW. He's got this series that you should all check out called Below the Ten.

MOLLY: Ooh!

ANDY: And if you want to know more about that, maybe listen to ...

ROBERT: Below the ten what?

ANDY: It's a series about people, like very one of a kind, interesting people who live in LA. It's called Below the Ten. If you want to hear it, find links to it, or hear little snippets from the archive, you can find all that on our website. That's a thing you could do. I don't know if that's a thing we should say.

ROBERT: Which is Radiolab.org.

ANDY: That's it. Still it.

[ANSWERING MACHINE: Start of message.]

[LISTENER: Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad, Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Soren Wheeler is senior editor. Jamie York is our senior producer. Our staff includes Simon Adler, Brenna Farrell, David Gebel, Matt Kielty, Robert Krulwich,Annie McEwen, Andy Mills, Latif Nasser, Malissa O'Donnell, Kelsey Padgett, Arianne Wack and Molly Webster. With help from Alexandra Leigh Young, Stephanie Tan and Micah Loewinger. Our fact checkers are Eva Dasher and Michelle Harris.]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.