Dec 15, 2023

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

LATIF NASSER: Hey, this is Radiolab. I'm Latif Nasser. Today I want to tell you a story that—well, it started with a cold email that I got a few weeks ago from the person it happened to.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Hey, Latif.

LATIF: Hey, good to see you!

BLAIR BIGHAM: Likewise. Sorry I'm a bit late here.

LATIF: This is Blair Bigham. He is a doctor in Toronto. And the email, it almost felt like a confession.

LATIF: This is like a very—it's a very vulnerable pitch.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Yeah, thank you for saying that. It's been—it's been very weird, and I knew that I would want it shared, I just didn't know when.

LATIF: And so I called him up to talk to him about it.

LATIF: Okay, well let's—okay, let's rewind back to the beginning.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Sure.

LATIF: How did you get into medicine, or even just this area in general?

BLAIR BIGHAM: Yeah. So I mean, swimming for me was my childhood. The memories that I have are going to the pool. And what do you do as soon as you can when you're a swimmer? You go and you become a lifeguard.

LATIF: Right.

BLAIR BIGHAM: And so that was my entry into, you know, chest compressions, defibrillators, the idea of saving a life. And I remember that feeling of jumping into a pool for the first time to pull somebody out who was struggling. And I remember just being like, "That was the coolest feeling ever!" And, you know, growing up watching ER and Baywatch, it's like you get the sense that you can go and really save people's lives.

LATIF: And that possibility just hooked him.

BLAIR BIGHAM: I was like, "That's it. My next move now is to become a paramedic."

LATIF: And so he goes to school for it, and for the next decade or so he's riding around in ambulances ...

BLAIR BIGHAM: Talking on the radio to the dispatcher.

LATIF: Using the defibrillator paddles.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Doing CPR. Pulling people out of cars.

LATIF: He was saving lives.

BLAIR BIGHAM: I was, like, living my dream and loving every minute of it.

LATIF: Until one day and one very particular call he got.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Yeah. So I mean, I was working part time as a flight paramedic.

LATIF: A flight paramedic?

BLAIR BIGHAM: Yeah, I was working on a helicopter in Toronto.

LATIF: Wow!

BLAIR BIGHAM: And we picked up this woman who had been struck by a dump truck, and for about 45 minutes me and John, my colleague that day, we worked our butts off. We were drenched in sweat. We were working as fast as we could to pour more blood into her as fast as she was losing it, try to keep her oxygenated. Like, we did everything. And we got to this hospital, and we got into the resuscitation bay, and the surgeon, who I respect and admire, puts an ultrasound probe on her heart and he says, "We're done here." And it was the most jarring moment I can think of in my career. The moment of him saying "We're done," it's like you just got hit by a baseball bat. Like, you're sweating, you know, there's blood all over you, your heart rate's probably 130, right?

LATIF: Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Like, you have just been basically running a marathon to save this person's life, and all of a sudden it ends. I just remember feeling very confused and sad that day. I was like, I'm never gonna let anybody feel the way I felt that day. I was really impacted by it.

LATIF: And so Blair became a doctor himself. Fast forward a couple years, he's on a fellowship at Stanford University in the ICU in 2020.

BLAIR BIGHAM: And I end up locked in Stanford Hospital during the pandemic, as every ICU doctor and ICU fellow was, doing our very best to—to save COVID patients.

LATIF: And Blair says they were saving a lot of people.

BLAIR BIGHAM: The technology is amazing. What we can do now that we couldn't do even 10 years ago, 20 years ago is absolutely incredible, and it's why I'm a physician.

LATIF: But also, he started to notice this other thing happening, this thing that as a paramedic he'd never really been around long enough to see.

BLAIR BIGHAM: There comes this point where, after taking care of somebody for a little while, you and everybody around you starts to realize that they're not getting better. And so then I began getting a little bit uncomfortable of how we were keeping technology—or even adding more technology to people's bodies when it was very clear that they were never going to survive.

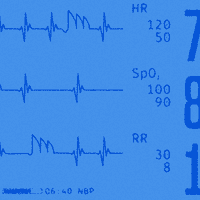

BLAIR BIGHAM: Once you're on life support, once you're on those machines, it's really, really hard for you to die. I can adjust everything about the way your body functions. I can adjust your pH, I can adjust your hemoglobin, I can adjust the amount of air that moves in and out of your lungs and how much oxygen is in that air. I can adjust your blood pressure and your heart rate. I take over total control. And normally, there's a curve. You get a bit sicker and then you kind of plateau, and then you get a bit better, and then we take off the life support, and then you go home. And sometimes the life support intensity just keeps going up and up and up and up, and there comes a point where you start to feel like you're hurting instead of helping.

LATIF: Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Where nobody around you, none of your colleagues believe that this person's gonna survive, none of the data suggests that they're gonna survive. And yet we're obstructing them from crossing that finish line.

LATIF: And as Blair spent more time in the hospital, he started to see more and more extreme examples of this.

BLAIR BIGHAM: I had a mentor who had a patient who was brain dead. And so this patient is clinically dead, but their family sued the hospital to keep the patient on a ventilator. And so for 400 days that ICU bed was occupied by a dead person. And while I feel for the family, obviously you would never want a family to think that you've declared death inappropriately, I think that's wrong on so many levels.

LATIF: He felt like it's just a waste.

BLAIR BIGHAM: It doesn't make any sense.

LATIF: You know, of time, of money.

BLAIR BIGHAM: It costs over a million dollars a year to keep someone in an ICU bed.

LATIF: But more importantly ...

BLAIR BIGHAM: Nobody wants to die that way. No one has ever told me, "I want to die attached to a bunch of machines, sedated and unaware of my surroundings."

LATIF: And as Blair thought about this case and other ones like it, he started to notice this kind of contradiction. You know, he'd gotten into medicine to save people's lives, to keep them from dying too early, but that very desire was causing some of his patients to die too late.

BLAIR BIGHAM: And that can be as great a tragedy as people dying too early.

LATIF: Sometimes ...

BLAIR BIGHAM: The most humane thing we can do, the most loving thing that we can do for this patient is to stop applying ourselves to them, and let nature take its course.

LATIF: So Blair has this realization, and in September, 2022 ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, host: In his new book called Death Interrupted: How Modern Medicine is Complicating the Way We Die ...]

LATIF: ... he writes a book about it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, host: Dr. Blair Bigham joins us now in studio. Welcome.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair Bigham: Thank you.]

LATIF: And it gets a bunch of attention.

BLAIR BIGHAM: I did a decent amount of media. It made the two bestseller lists here in Canada.

LATIF: Started a lot of people across the country talking about it—including his own family.

BLAIR BIGHAM: I mean, my mom was, like, "Oh my God, we need to have a power of attorney, and we need to talk about all of this."

LATIF: Did that ever happen? Or it was just a conversation, like, "Oh, we should do this."

BLAIR BIGHAM: Yeah, yeah. It was all talk.

LATIF: I'm in the same place with my parents, I feel like right now. Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Yeah, it's such a—I mean, I fucking wrote a book saying, "Oh, you have to have this conversation," and I'm like, "Oh my God, I haven't had the conversation with my own parents." Anyway, two months after my book comes out, you know, I've gone on this speaking tour, I've been like, "Yeah, we use too much technology. Sometimes it's okay to let people die." And my mom called me and said, "Your dad—like, there's something wrong with your dad's stomach. He's been complaining about it for a couple of days." And my life got turned upside down.

LATIF: That's when we come back.

LATIF: I'm Latif Nasser. This is Radiolab. Just before the break, ICU doctor Blair Bigham, on the heels of a book tour advocating for less intervention at the end of life, got a phone call from his mom.

LATIF: Are you the one in your family that when anyone is sick or whatever they call you?

BLAIR BIGHAM: Oh my goodness. Every doctor will lament about, if you're the only health care—or nurse, or paramedic—any health care professional, if you're the only one in the family, you're getting these text messages and photos of rashes and questions about baby's fevers and ...

LATIF: Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: ... it's all coming to you.

LATIF: Right.

And so I didn't think too much of it when my mom calls and says, "Oh, like, something's really wrong with your dad's stomach." And I said, "All right, well, Dad's 75 and he's having abdominal pain. He needs to go to the emergency department and get a CAT scan."

LATIF: Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Period.

LATIF: Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: And of course he doesn't. And then a few days later, my mom calls me back and I say, "Well, what did the CAT—like, what did the doctor say?" "Oh, he hasn't gone."

LATIF: Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: "Well Mom, you just have to put him in the car and take him to the hospital, and you tell the emerg doc that your son is Blair Bigham, he's an emergency doctor, and he says you need a CAT scan."

LATIF: Right.

BLAIR BIGHAM: And so they go to the emergency department, and the doctor doesn't order a CAT scan. And my dad is not the type of person who's gonna go in and say, "My son's a doctor. Give me a CAT scan." So he probably said something, you know, passive.

LATIF: I also have very polite Canadian parents, so I know how that goes. Yes.

BLAIR BIGHAM: [laughs] And my dad—I know my dad. My dad just would have wanted to get the hell out of there, right? He doesn't want to be in a big, crowded emergency department.

LATIF: Right. Sure.

BLAIR BIGHAM: Anyway, so my mom calls me back, right? "It's still really bothering—" Okay, mom." I pull out my schedule, and I say, "Tomorrow, at 10 am, my friend Scott starts his shift at my emergency department. You're gonna go tomorrow at 10 and you're gonna ask for Scott McGilvray, and you tell them you're Blair Bigham's parents, and Scott's gonna take very good care of you." And I shoot Scott a text and I say, "My dad's coming in with belly pain. He's already been on a PPI. Like, figure it out." And I have no—I don't think anything is gonna show up, right? And then the next day I'm at work in the ICU, and my phone rings and I look at it, and it's Scott's number. And I say okay, so I kind of start walking out of the ICU because, like, I'm gonna have a conversation. And I answer the phone and Scott says, "I'm really sorry Blair, but I have some really bad news for you." And then he starts reading the radiologist's report.

LATIF: Yeah.

BLAIR BIGHAM: "There's a four-centimeter pancreatic mass invading the stomach." The minute Scott started reading I said, "Fuck, that's a fatal pancreatic cancer." The reason pancreatic cancer is so famous and so deadly is because it grows silently until it's too big to cut out. And so the people who survive pancreatic cancer, it gets picked up before it becomes symptomatic through some sort of a good luck situation because they got a scan for something else.

LATIF: But in the case of Blair's dad, it seemed like ...

BLAIR BIGHAM: It was probably too late, and his cancer was of the type where you're talking about months, not years. And so I was just—I don't even know. The next—the next 12 hours of my life are a total blur. I couldn't leave the service that I was on. I had to keep caring for people, but I was just—I have no idea if I did a good job at work that day or not. I just could not think of anything. An hour or two later, I called my dad and I said, "Did Scott talk to you?" And he said, "Yep." And I said, "Do you have any questions?" And he said, "No, not right now." And I said, "Okay Dad, I'm getting you into a surgical consult because we need surgery. If it's not operable, like, then you've only got a year to live. Like, we have to get you surgery." And so then I did the most irrational stuff. I called the best pancreatic surgeon in the country and harassed his administration staff to get me in touch with him, and said, "I need you to see my dad tomorrow." Because I had hope that no—that even though the odds were slim, that that surgeon was gonna say, "I can cut this out of you and that yeah, you might need a bit of chemo after but, you know, like, this is survivable." Like, that's what I was waiting for.

LATIF: And so within a couple of days, there they were, Blair and his parents sitting in this doctor's office.

BLAIR BIGHAM: And the surgeon came into that room and was clear as day. "There is no surgical option." And we were just silent. We were just sitting there, because I had set the expect—I said, like, "If it's not surgical, then it's going to kill you." And I had told them that before the meeting. And so I remember sitting in that clinic office when the surgeon said, "I cannot cut this out of you." And my dad just looked at me. I remember his facial expression of just being like, "There it is." It was—that was the moment that he knew that he was gonna die of pancreatic cancer. And then I remember sitting in the Tim Hortons coffee shop with my mom and dad immediately after meeting with this top surgeon, and even though I knew that there was nothing they could do because I'd seen so many people die of pancreatic cancer, I was just so spun. I just went down that rabbit hole of what else can we do here? Can we do genetic testing on the tumor to see if it's susceptible to some special study drug? You know, like, I kept having ideas of, like, well what about this, what about that, what about this?

LATIF: It's almost—from the outside, to hear you tell this story, like, you have all of this training, you've gone through this a million times. And then it happens with your family, and it's like, none of that counts for anything. Like, you're just ...

BLAIR BIGHAM: None of it, no. Like, I'm just spinning about all the ways my dad could die.

LATIF: Right.

LATIF: And so, despite everything ...

BLAIR BIGHAM: He started chemotherapy, and whenever I would propose this, that or the other thing, my dad would say something like, "Yeah, yeah, yeah. Okay, yeah. Okay, we can do another CT scan. Okay yeah, we can do that. Okay yeah, we can do that."

BLAIR BIGHAM: And then for the month of February, he actually felt pretty good. And then in March I got another phone call from my mom that he's vomiting. And when you have pancreatic cancer and you're vomiting, there's only one thing that's going on and that's the mass in your stomach has blocked off where the food exits your stomach and so your stomach can't drain. And that's what happened to my dad.

BLAIR BIGHAM: And later that night, the hepatobiliary surgeon called me and said, "There's nothing I can do for your dad. There's nothing else that I can do." And so then I started saying things like, "Well, what if we did a post-pyloric feeding tube, or can we—" And he said, "Blair, stop. I'm telling you that there's nothing that we can do right now." And then I remember we were talking with the surgeon around the bedside, and I kept saying, "Well, what about, like, can we switch to FOLFOX? Like, can we switch chemotherapy regimens?" And my dad yelled my name in, like, a very gruff way, and said, "I just want to be comfortable. We're done here." And I looked around the room, and I was just like, "Okay, this is that moment. I'm the crazy, whack-a-doodle son that I'm so used to seeing in the ICU where I work." And then that was it. And then it was palliative care, and he died three weeks later.

BLAIR BIGHAM: I was in that zone. I was in that physician-scientist zone of, like, "Fix this." I couldn't just sit there beside him. It was—I just found it infuriating to just sit there, knowing that this cancer was just growing in his abdomen. I couldn't handle the idea that there was nothing left to do here. I just couldn't get comfortable with that, even though I promote it so often. I wrote a book about how people should value palliative care and the ICU, and here I was saying, "But not with my dad."

LATIF: The—the question that I have is like, oh my God, if Blair can't let go in this moment, if you can't do it ...

BLAIR BIGHAM: Yeah. How can anyone else?

LATIF: How can anyone else?

BLAIR BIGHAM: I don't know. I mean, I have been—I have seeped myself in this topic for four years now, and I—I don't have the answer yet.

LATIF: I want to end this story about endings with a beginning—a beginning that Blair's dad gave to him in his final days of life.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: Okay. So we've got a bunch of candles here.]

BLAIR BIGHAM: On December 23, just before Christmas, my fiance, Fernando and I got married.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: So Fernando, place this ring on the third finger of Blair's left hand. "Blair, I give you this ring."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Fernando: Blair, I give you this ring.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: "As a symbol and pledge ..."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Fernando: As a symbol and pledge ...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: "... of the covenant we've made between us."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Fernando: ... of the covenant we've made between us.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: Blair? "Fernando, I give you this ring."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair Bigham: Fernando, I give you this ring.]

BLAIR BIGHAM: And my dad, with a nasogastric tube shoved down his nose, draining his stomach into a bag, with a rubber band around his arm officiated.

LATIF: Whoa!

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: "As a symbol and pledge ..."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair Bigham: As a symbol and pledge ...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: "... of the covenant we have made between us."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair Bigham: ... of the covenant we have made between us.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Blair's father: Ladies and gentlemen, I present you the married couple, Fernando and Blair. [applause]]

BLAIR BIGHAM: The wedding is how I'll remember my dad. So I mean, yeah. Yeah.

LATIF: That's it for this week. This episode was reported by me with help from Simon Adler, and it was produced by Simon Adler with help from Alyssa Jeong Perry. It was edited by Pat Walters, and we had mixing help from Arianne Wack. Special thanks to Lucie Howell and Heather Haley.

LATIF: One very last thing: for The Lab members out there, we just dropped a bonus earlier I think you should check out. It's an interview I did with one of our fact-checkers, Diane Kelly. She's so fun and funny and good at her job. It was such a pleasure to do, and I think it'll be fun to hear.

LATIF: If you're not yet a Lab member, you can become one at Radiolab.org/join. You get those kinds of bonus drops every once in a while as well as exclusive swag, access to the entire Radiolab archive ad-free. It's pretty fun! Radiolab.org/join. For yourself, for a holiday gift for a loved one. I guess for an enemy too, if you—why stop at loved ones? That's all. Thank you so much. Catch you later.

[LISTENER: Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is edited by Soren Wheeler. Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are our co-hosts. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, Becca Bressler, Ekedi Fausther-Keeys, W. Harry Fortuna, David Gebel, Maria Paz Gutiérrez, Sindhu Gnanasambandan, Matt Kielty, Annie McEwen, Alex Neason, Alyssa Jeong Perry, Sarah Qari, Sarah Sandbach, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster, with help from O. Rose Broderick. Our fact-checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger and Natalie Middleton.]

[LISTENER: Hi, this is Ellie from Cleveland, Ohio. Leadership support for Radiolab's science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox, a Simons Foundation initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.