Apr 3, 2020

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

JAD ABUMRAD: Do do do do do do. Molly Webster.

MOLLY WEBSTER: I wonder how long it'll ring for.

JAD: [laughs] Hey.

MOLLY: Hi.

JAD: It rings for an awful long time before it makes ...

MOLLY: [sighs] How do I sound?

JAD: You sound amazing.

MOLLY: Okay, great. Because I'm in quite a contrived setup right now, but ...

JAD: Are you in your closet under a blanket?

MOLLY: Yeah. Got a desk mic from the station after my mic that I ordered got stolen off my front porch. I'm gonna do one thing. I'm gonna take off my hat. Give me a second. Mic down. Take off the ...

JAD: I'm Jad Abumrad. This is Radiolab. That voice, of course, is Molly Webster. This is Dispatch number three, which has to do with a bit of science that I feel really captures the spirit of this moment on so many levels. We're gonna tell you about that, and then second, we're gonna play you an interview that really kind of knocked us all on our butts.

MOLLY: Great. Okay, so I'm recording on this end, so we've got a back up.

JAD: All right, Webster. Are you—did you get your two-hour PhD? [laughs]

MOLLY: [laughs] Do you mean my 35-minute PhD?

JAD: Okay. So where in the cluster—where in the just helter-skelter mayhem of the last two weeks did you bump into this idea?

MOLLY: It was thinking about treatments, basically. Because, like, the holy grail that everyone keeps talking about is a vaccine. And thinking about how that vaccine, you know, the estimates are 12 to 18 months. And even in vaccine-land that's pretty generous, like, as far as a fast timescale goes. So, like, what happens in the interim time? There are options on the table where they're like, "Hey, there's this drug that we've seen in the lab do well against coronaviruses in mice. Maybe we grab that drug and we try it here." They're repurposing, like, rheumatoid arthritis drug treatments, and they're repurposing drugs that they tried in the Ebola crisis but didn't work but maybe they'll work here.

JAD: Right.

MOLLY: So there's actual stuff like that happening. But the thing that jumped out at me the most, probably because of its, like, immediacy and the potential for, like, now—of using it now, is blood transfusions.

JAD: Blood transfusions.

MOLLY: [coughs] I don't even know what that means, right?

JAD: Right. What does that mean?

MOLLY: Because it has one more word in it. It's blood plasma transfusions. So suddenly you're like what is a blood transfusion? And then, like, what's plasma?

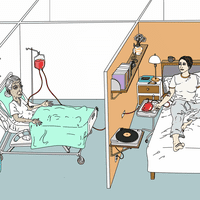

JAD: Maybe this is something you've seen mentioned in the press in the past couple of days. To my mind, when I hear the words "blood transfusion" I think of those medical drawings from the 1700s where you see a tube running from one person's arm directly into another person's arm. The idea in this case, in brief, is that we're, you know, standing in this tragic gap, right? This is what I talked about in the last dispatch. We know a little bit about this virus, but not nearly enough to be able to fight it effectively. And we need to do something now. All the while, we do notice this difference that some people on their own seem to fight off the virus just fine. They have very mild symptoms. Others get very very sick. We don't yet understand why there's that difference, but maybe we could use it.

MOLLY: The thought is, okay, if there's a coronavirus person—if there's someone who had coronavirus and they survived, they survived because of some reason. Like, their body did something well and scared off this virus and crushed it, and they lived. And so maybe if we tap into that body as a resource and take from it the thing, the part of it that fights off viruses, literally get it out of the survivor into a sick person, maybe we can save the sick person.

JAD: Oh, wow!

MOLLY: And so it's very crude. It's super crude.

JAD: It's sounding super medieval all of a sudden, the way that you're saying it.

MOLLY: I know. I know. Like, what century are we living in? [laughs]

JAD: We don't really know why it works but it kind of works, so just get that in there!

MOLLY: It's like, and we know that it's, you know. safe in the sense that that blood was in another person. Like, it's almost like you've already done a human trial. Like, if you take my blood from me, it didn't hurt me, right, so I'm giving it to someone else. And we've also ...

JAD: Couldn't there be bad things in that blood? Couldn't there be like a—couldn't there be bad stuff?

MOLLY: Okay. Right, right, right. Let me explain how it works. So you would take somebody who has survived coronavirus. You would stick them in a chair, you would stick a needle in their arm. And then you would take their blood, you would filter out the blood plasma, leaving behind the red blood cells and the white blood cells. You would take the plasma and you would put it into a patient who currently has coronavirus.

JAD: Now wait. What is plasma?

MOLLY: So, you know, plasma is the part of the blood that doesn't contain any living cells. So it doesn't have white blood cells, it doesn't have red blood cells, but it has the other stuff that makes up your blood. And the thought is is that the blood plasma is the part of the blood that holds anything that might have fought against an illness. Like, the antibodies, right? And so antibodies are the things that your body makes to fight an intruder. So a virus comes in, and we make an antibody to attack that virus. And then you have—it's almost like your body makes its own drug.

JAD: I see. So if I survived the coronavirus, that means that for reasons that we don't really understand, I have some special drug in my blood plasma that can maybe help someone else fight it off too.

MOLLY: Yeah.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: If you look at the different options that are out there, this has a good likelihood of working.

MOLLY: This is Arturo Casadevall. He's an immunologist at Johns Hopkins University, and was really the first person in the States to say we should start doing this.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: I have been working on antibodies for my entire academic life. And I like history, and I read a lot about the history of how antibodies were used.

MOLLY: This is not the first time we've thought about doing something like this. We've actually been doing it since the 1890s.

JAD: What was it used for initially, like, in the 1890s? What—was it like tuberculosis or ...?

MOLLY: They first used it for diphtheria.

JAD: Ah. I'm not sure I know what diphtheria is.

MOLLY: Well here, wait. Let's look. I don't—I couldn't actually—diphtheria. I couldn't actually explain what the—"Diphtheria is an infection caused by a bacterium. Diphtheria causes a thick covering in the back of the throat. It can lead to difficulty breathing, heart failure, paralysis."

JAD: Hmm. And so they used it on that?

MOLLY: Yeah.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: And in that case, the serum didn't come from people, it came from horses.

JAD: Ooh!

ARTURO CASADEVALL: Yes.

JAD: Did that work?

MOLLY: It did work. But then they realized you could do it with human blood, too.

JAD: Ah.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: By the way, it was used in 1918 in the influenza epidemic.

JAD: Hmm.

MOLLY: I wonder why they got that idea then.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: Oh, because it was known at the time that people who recovered from infectious diseases made antibodies. That was known. The first Nobel prize, by the way, in 1901, was given to Emil von Behring for the—for this discovery, that you could transfer immunity ...

MOLLY: Oh!

ARTURO CASADEVALL: ... by transferring serum.

JAD: Wow.

MOLLY: You know, they used it in the '20s for scarlet fever. They did it in a measles outbreak in Pennsylvania in the '30s. It seemed to—seemed to stop an outbreak.

JAD: Oh, so people got better?

MOLLY: Oh, yeah.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: However, that practice was largely abandoned after 1950 for two reasons. One, vaccines came on board. And the other thing was that they discovered that blood, in some circumstances, could carry infectious diseases.

MOLLY: Then you have an interesting thing where, like, the AIDS epidemic, you know, if you think about HIV, that's definitely pathogen in blood. So you see a bit of a pause. And in any blood story you see a pause around ...

JAD: Oh, that's really interesting.

MOLLY: ... the AIDS crisis. But then technology improves, we have so many ways of screening blood and screening blood really quickly. You start seeing them using it in the SARS epidemic. It's been used in MERS, that—that respiratory infection, which is a coronavirus. It's been used on other coronaviruses, basically.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: So when I saw that this was happening and beginning to spread through the world, I knew that this could potentially be used. This could provide an option. Obviously, you know, like any therapy, it needs to be tested. And I reinforce that over and over again. That one needs to look at this as an experimental therapy, especially ...

MOLLY: As of this week, which is, you know, the second-to-last week in March, the FDA has given, like, emergency approval to both start investigating, like, the plasma transfers, you know, with clinical trials and sort of, you know, scientific protocol. But then they've also okayed it for compassionate use. Which is that, like, if you have a case and they seem like they're failing, can you—can you use it?

JAD: I see.

MOLLY: You can now use it. That's what the FDA is saying. You now can use it.

JAD: And this is happening in New York, right? I mean these are—it's just starting.

MOLLY: Yes. So Mount Sinai in New York and Albert Einstein Medical College have said that they hope to start using it in patients on the ground the very beginning of April, essentially. And Arturo and the other scientists involved in this were saying one of the amazing things about doing the plasma transfers is you're gonna find out really quick if it works.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: This isn't gonna be one of those trials that requires years to be completed. I think that there is a good likelihood that we—that once you deploy this, that you will know whether it's working in a few weeks. That this is something that can—can be tried today.

JAD: Okay. Wow! Okay, so let's get—getting back to so many things.

MOLLY: Okay.

JAD: But wait a second. But wait a second. Wait—but wait a second. Wait—but wait a second. Wait a second. ipDTL, chill out. Chill out, ipDTL. Okay.

MOLLY: Hold on, let me look at mine, too.

JAD: We're good. We're good.

MOLLY: Okay. We're doing good. Okay, so we were at ...

JAD: Why—why isn't it been like—like, ramped up at scale? I mean, there's no way for you to know this answer.

MOLLY: Because there's not really a scale. Like, it's like, you have to find people who had the illness, and you have to take their blood from them and you have to make sure that blood is healthy. Then if it is, you take their plasma from them and then you give it to someone else. That's really kind of like a one-to-one ...

JAD: But that is interesting Molly, because it's like, maybe this is the—okay, I'm just gonna go wild with conjecture for a moment.

MOLLY: Do it.

JAD: Maybe this is the scale moment because you have so many people who are infected ...

MOLLY: We have so many.

JAD: And they're all in the same place. And some of them are getting better magically and some of them aren't. And so you have, like, the ability to do like a massive ...

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: ... a natural experiment, you know?

MOLLY: But the other thing is is that, so China's actually been doing this I think since January for their outbreak with—with this COVID-19.

JAD: How—they've been doing transfusions?

MOLLY: They've been doing this serum transfusion, yeah.

JAD: Wow!

MOLLY: And so—and the reports are that it's going well, though nothing's published yet.

MOLLY: I mean, I guess I don't quite understand why it wouldn't work. It's like, you take someone's blood that defeated the virus and you give it to someone else and it seems like, wouldn't it do the same thing?

ARTURO CASADEVALL: So one of the problems with this type of therapy is that it works best early. Antibodies work best early in the course of disease.

MOLLY: And the question is, when is 'earlier?' And with COVID-19, that's a tricky question because often you have a viral count that's growing before you have symptoms.

MOLLY: And so—so a lot of times people aren't even seeing people until it's, like, really bad. So, it makes it tricky.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: Right, but I think there is a big difference between really bad and the intensive care unit.

MOLLY: Oh, okay. Okay.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: And maybe this intervention, we—and again, I stress that this will be a clinical trial. This is a hypothesis that needs to be tested. The administration of—of plasma at that point of view, may—may prevent progression of the disease. So it's that people don't get into such trouble that they have to be on a respirator.

MOLLY: And so it looks like in the States, they're gonna break it down. Like, in New York, they're gonna target, like, these three different groups. So they're gonna target severe patients who really need help and are at risk of dying. They're gonna target early patients who are just showing symptoms. And they're also—they also want to use it prophylactically, so actually giving it to doctors and nurses who have no viral count, who are coronavirus negative, and see if it can actually be a preventative.

JAD: Whoa! That feels new.

MOLLY: Yeah. And that's actually pretty cool.

JAD: That's really cool. That feels to me like—wow, that feels to me like if they could do that, they should just do that, you know?

MOLLY: I mean, I would take it now.

JAD: Totally.

MOLLY: And, I'm in my closet. [laughs]

JAD: No, I know. I mean, I'm thinking about my sister-in-law who's a nurse who is treating COVID patients and man, if there was something that could help her it's like whoof!

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: I mean there's something kind of like—just to pan out for a second, it's like as a paradigm it's such an interesting, intimate way to treat because I mean, these days, you know, like, the whole field of medicine seem to be moving toward little pills that you—that you pop and you just drink. You take these pills and they do something mysterious in your body and you feel better. This is so intimate in that it's one person having suffered and survived, then turning to the next person who's a few days behind them suffering and saying, "Let me help you." There's something very spiritual in a way, about that.

MOLLY: Yeah. I find it—when Arturo and I were talking about it on the phone, it felt very profound and, like, really beautiful in the sense, like, he talked about it as, like, sharing immunity. Like, we can pass immunity to each other. And I thought, "Wow, short of social distancing where we're all staying in our houses to protect as many people as we can, that feels like such a golden gift." Like, to be able to transfer something so profound to a person as, like, protection, it's like you can shepherd someone in, it's like you can offer them safe passage. And it's—it's safe passage. And it's ...

JAD: Safe passage. Yeah.

MOLLY: Safe passage at such a metaphorical level.

JAD: It's the same thing that I get when I hear about people donating kidneys, you know? But this is—this is somehow different.

MOLLY: Because they've had it. Like, it's one thing to just, like, give a donation.

JAD: Yes.

MOLLY: It's another thing to say, like, "I had this experience, and I'm gonna hold your hand through it. And I'm not physically holding your hand, because none of us are allowed, but I'm, like, spiritually holding your hand because I'm giving you my blood, and I'm—and I'm helping you walk this path. I'm helping you take this journey."

JAD: Coming up we talk to somebody who, in a way, is taking that journey. That's after the break.

[LISTENER: Hi, my name is Gonda Vialone, and I'm currently quarantined in Champaign, Illinois. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org.]

[phone rings]

TATIANA PROWELL: Hello?

MOLLY: Hi, is this Tatiana?

TATIANA PROWELL: Yes, it is.

MOLLY: Okay. Hey, it's Molly from Radiolab.

TATIANA PROWELL: How are you?

MOLLY: I'm good! Can you hear me okay?

TATIANA PROWELL: Yeah, I can hear you fine. Can you hear me?

MOLLY: I can, yeah. There might be—there's, like, I think ...

JAD: Hey, this is Jad. This is Radiolab. We are back. Just wanna play you now an excerpt of an interview that Molly did with someone who is really right in the thick of this stuff.

TATIANA PROWELL: So my name is Dr. Tatiana Prowell. I'm an internist and medical oncologist on faculty at Johns Hopkins in the Breast Cancer Program.

JAD: And Molly ended up talking to Tatiana because of a tweet that she posted.

MOLLY: Can you tell me in your own words what the tweet was about, and what it said?

TATIANA PROWELL: Sure. So the tweet was about my brother-in-law's dad—we call him Papa Doc, he's actually an internist in California. I called him—you know, I talked to my brother-in-law about something else, actually. And I just said, "How's everybody?" and he said, "Oh, my dad's a little under the weather." And I said, "Wait. Wait. How? How is he under the weather?" You know, he's 83, he's practicing medicine, he's high risk, right? And he said, "Oh well, he's just been coughing a little bit. I don't think he's had fever or anything." And I literally said, "I'm gonna call him. I'll call you back."

TATIANA PROWELL: And I hung up and I called him. And he said, "Oh I'm fine, I've just had a little bit of a cough, but I actually feel fine. I'm not short of breath at all." And his wife volunteered, "Yeah, he seems fine, he looks fine. He's just been napping more than usual. Normally he doesn't just nap during the day, and he's been napping. He's been falling asleep in the couch and so forth." And I said "All right, that's it. You guys are going to urgent care right now. I think you're hypoxic, I think your oxygen level is low." They thought I was being crazy. And I said, "We're just gonna talk about one thing before you go, and that is whether or not you are willing to be intubated." And he actually laughed! He was like, "I just have this dry cough! Like why are we talking about a ventilator?" And I just said, "I'm worried about you because you're falling asleep inappropriately and you're 83. And you're a doctor, which means I'm sure you've been exposed to these patients." And he said, "Yeah, if you think I should do that."

MOLLY: Wow!

TATIANA PROWELL: And I just said, "Listen, you know, we can support you, but you have to go right now, because I think you have COVID-19." And he went to the urgent care straight from that call. He hung up, he went. His oxygen saturation was 92 percent, it should be 100 percent. They sent him directly from there to the ER. And he has COVID-19 illness, and has been hospitalized now for a little over a week.

MOLLY: Wow!

TATIANA PROWELL: And is in their Intensive Care Unit in a community hospital. In fact, the same community hospital where he was on staff for many decades. And so my tweet was asking if there was anyone who had had COVID-19 and recovered, and who was interested in serving as a potential donor of plasma in Southern California, where he's currently hospitalized.

MOLLY: And how did you—I mean, I guess you're a doctor, so maybe you're in the zone, but you're about to tell me. Like, how did you know even to think about asking for plasma or, like, think, like, "Maybe he could get a plasma transfusion?"

TATIANA PROWELL: Yeah. I think it's a mix of things. So one is that I'm on faculty at Johns Hopkins, and as I believe you know, a lot of the work that is going on with convalescent plasma has been centered there. And the other thing is that my husband is an infectious diseases physician in the Navy. And so—and he's actually ...

MOLLY: Oh man, all-star family.

TATIANA PROWELL: [laughs] We're—we've been bouncing a lot of ideas back and forth about how best to take care of people with this. And of course, this is not a new concept. You know, no one just got the idea to give convalescent plasma right at this moment for the first time. This has been done going back more than a hundred years. And it's a way, honestly, for people who've experienced this illness and recovered to contribute at a time that I feel like the public really wants to contribute, you know? I think that that's a thing I sense so much from my friends and family and neighbors and everyone who's not in medicine is they're all—they're all rooting for us who are in science and medicine. But they're all at the same time feeling kind of like they want—they want to do something.

TATIANA PROWELL: They have this restlessness. Everybody's quarantined. Everybody's kids are home. They're watching the news or they're watching social media, and they're feeling like this catastrophe's unfolding and they're just sitting there. I think that—I think that there is this sense that we're at war, and the war is being fought by a very small number of people. There will be millions of cases in the US before this is over. Millions and millions. And not all of those people will be qualified to donate plasma, but many of them will. And so it's a great opportunity.

MOLLY: I have to—like, I'm like, what happened with your tweet? Like, did you get blood? [laughs]

TATIANA PROWELL: [laughs] So—oh gosh. Well, I tweeted that late at night. I can't recall what time it was. But it was—it was late. And honestly, I didn't expect it would get a lot of attention. And within minutes I had hundreds of people commenting, retweeting, private messaging me, telling me, "This is my blood type." You know, "This is how many days ago I was sick. Where exactly do you need me to go? Which day? I can see if I can get off of work." I mean people just ...

MOLLY: Really?

TATIANA PROWELL: Came out of the woodwork. I had people messaging me with a—with a PDF of their—their test results, to show me what day it was positive. I mean, I just got all kinds of stuff. And they were suddenly not just contacting me as a donor, suddenly people just realized, "Oh, my gosh! There are hundreds of people that want to donate. My family member needs plasma!" So then suddenly, I had people messaging me saying, "We're looking for plasma. Help! Like, have you gotten anyone who's in New York? Have you gotten anyone who's in Louisiana?"

MOLLY: Wow!

TATIANA PROWELL: "Do you have anyone who's this blood type?" So suddenly I was sitting on my bed trying to match these people up, and I spent pretty much three days in my pajamas on my bed trying to match people up. It became, you know, complex because it's really impractical, right? That's not the way to do it.

MOLLY: You're only one person.

TATIANA PROWELL: Exactly.

MOLLY: I mean, how did you feel, like, having the weight of all of this on you? Like, were you like, "Am I gonna find a donor? Am I not gonna find a donor? People think I'm gonna find a donor and what if I don't? I want to save this but I can't."

TATIANA PROWELL: You know, I think I was always—I was always confident we'd find somebody.

MOLLY: How come?

TATIANA PROWELL: Well, a few things. One is I'm an oncologist. And you talk to a handful of oncologists, I think a thing that you discover instantly is that oncologists are really optimists. Like, deeply optimistic people. Certainly oncologists of a certain age, and I put myself in that category, I'm 47. I think anyone who's been doing oncology for 10 or 15 or 20 years has to be an optimist because we were taking care of people with cancer when the treatments were really not very effective in a lot of cases, you know? We lost a lot of people. And you really have to, I think, come into it every day with the attitude of, "I might be able to save this person."

TATIANA PROWELL: I think the other thing, though, was just a kind of an understanding of statistics. I mean, it's a pandemic, right? It grows exponentially, the number of cases are doubling every three days or something. So I realized, you know, the same way that it didn't take very long for this—this outbreak to get completely out of hand and essentially close down the world, it also wasn't going to take very long for me to have a really large number of qualified donors who were—had been infected and recovered.

MOLLY: Did he—did you find a match online?

TATIANA PROWELL: We did actually find a match. And his—we just found a match. And the person lives a few hours away from where my Papa Doc is hospitalized. He actually has the first—same first name as one of the patient's sons, which they felt was very symbolic. And so the pheresis and transfusion is supposed to happen tomorrow, Tuesday.

MOLLY: Wow. So last question: what do the next couple of days look like for you, in the case of Papa Doc?

TATIANA PROWELL: Yeah. So he—you know he's—his donor is coming tomorrow and—and the blood draw will happen. And then the plasma will be tested and processed and transfused into him tomorrow with the expectation. And then we wait and we see. You know, I think that we're hoping that—that it will help him clear the virus pretty quickly. That's the hope.

MOLLY: Yeah.

TATIANA PROWELL: I think that having an infection, maybe even being critically ill from it, recovering. And then saying, "I know how awful that was, how scary that was, how—how absolutely uncertain everything felt when I was sick. And I have the capacity—me, myself. I can go give plasma, and if I give a plasma donation, like a plasmapheresis donation, where they take off three units of plasma, I can treat three people with this." That's it. Because, you know, it's interesting, every virus has a number that we call "R naught." It's like R sub-zero. "Are not" is how it's pronounced. And that number is how many people an average infected person will themselves infect. So if you look at, you know, some of our less contagious things like seasonal flu, those are closer to one. If you look at Spanish Flu, it was about two or a little more than two. So each person who got infected, on average, gave two other people the infection. And this—this virus, SARS COV-2, is closer to three. So that means everybody, on average, who's got it is gonna give it to three other people. So it feels kinda cool, like there's some kind of order in the universe, that each person who gets it, who donates plasma, can actually treat three people.

MOLLY: Wow, I didn't realize it was three. I thought it was at most two.

TATIANA PROWELL: Yeah, it's three. And I just, you know, the—what do I call it? I don't know what. The symmetry of that in the universe, that the R naught for this virus is three, and the number of people that a plasma donor can treat after they've been infected is three. It just feels like—I don't know, there's something beautiful about that.

MOLLY: Wow, you've given me a lot to think about. And also, just feels so good to just, like, share thoughts and ideas. So thank you for that, sharing your own and listening and responding back and stuff. Like, sort of in the middle of all this crazy.

TATIANA PROWELL: Oh, yeah. No, the "listen," that's the humanity in it, right? Like, that's the—if something good comes from all this, it's that we kind of just distilled down, like—like, all the unnecessary stuff is gone, right? Like, what's left is what really matters. Like, you're down to, "Do we have sufficient nutrition to keep our bodies going? Are we with the people that we love most, and are they safe? Are we able to do our most essential work, even if it's hard and it's made more complex?" You know, like, we really—I mean, that is—that is the little, tiny, tiny pearl at the center of all this is that it forces us to say, "What is essential?" And part of that essentialness is connecting with other people meaningfully, deeply. You know? That is a big part of it. The thing—the greatest tragedy, in my mind, of this entire illness—which we didn't touch on at all—is the fact that people die alone.

MOLLY: Yeah.

TATIANA PROWELL: So, you know, in the case of Papa Doc, a thing that has been really hard for our family was they sent him directly to the ER. And his wife called me and said, "We went there and they heard what his oxygen level was,and that he had been coughing and that he was a physician. And they took him right back into the isolation area as a PUI: a person under investigation for COVID-19. And they won't let me into the ER because I'm not symptomatic, and they don't want me to be exposed and I can't be with him because he's now in this isolation unit." And that's the last time she saw him. Like, she literally pulled up to the ER and he went in and she's never seen him again. And if he died, she'd never see him alive again.

TATIANA PROWELL: And that is the greatest tragedy. There's gonna be so much tragedy from this, right? We're gonna lose so much life. We're gonna lose lives of people that are on the front lines as first responders and as physicians and nurses. And we're gonna lose people who are young. But I think that amidst all that other tragedy, the biggest tragedy is going to be that hundreds of thousands, or millions of people before this is over will die alone. In many cases, these patients aren't even attended by a physician when they're dying. You have a phone call with them from outside the room. You only go in the room if you need to lay hands on the patient to do a procedure or something. These people are going into the hospital, they walk into the ER, they're coughing or something. And they don't know. They don't realize—I didn't even realize. I mean, I realized but I didn't think of it. I knew if he went in there that he would immediately be put into a room as a person under investigation, but I didn't—it happened so fast that I didn't say, like, "Tell him you love him. Like, spend 10 minutes in the car before you went—send him in. You've been—you've been living with him for weeks. Like, you've been exposed. Like, take 10 minutes. He's not critically ill. Take 10 minutes and talk to each other. Say what you need to say. Tell him the logistics stuff. Like, whatever you need to do, like, do it!"

TATIANA PROWELL: And I didn't think to do that. And I'm a physician. I knew that these people were being isolated, and it didn't occur to me. But for somebody who doesn't realize that, they drive their family member up to the ER and that's it. The people who die, they'll never lay eyes on them again. You know, I think a lot about death. I've attended a lot of death as an oncologist. A lot. Like, I can't—I've been a doctor for 21 years, and I've been an oncologist for, gosh, 17 of those—18—16 of those, or something? A lot—a lot of years. I can't even begin to guess how many deaths I've pronounced. I've been a witness to death a lot of times. And there are a lot of things that distinguish a good death from a bad death, you know? Being free of pain and having closed all your loops. You know, not feeling like you're dying with unfinished business on either side, on the part of the person who is dying or on the part of the survivors. Like, that's the thing. You know, if you're prepared, if you aren't surprised by death, those are the people who have a good death, you know? I think there's just some sort of peace and resolution in the end of suffering.

TATIANA PROWELL: These deaths are the exact opposite of that. It is the worst death. No one's prepared for it. No one has closed the loop. No one got the logistics ready. No one did the emotional hard work of making sure that everyone's said what they need to say and people have forgiven whom they need to forgive. And none of that's done. I don't know, it's a lot to—it's a lot to think about people dying alone. Are you still there? Hello?

[phone rings]

MOLLY: [laughs]

TATIANA PROWELL: Hello.

MOLLY: That was such a dramatic ending. [laughs] I'm so sorry!

TATIANA PROWELL: I know! I—No, I think that's how you should end it, actually.

MOLLY: I ...

TATIANA PROWELL: That's just—that's like the universe telling you that's the end.

MOLLY: You—you got isolated in the end while talking about ends of isolation. And I was like, "I can hear you and I can feel you, and I have, like, tears in my eyes, and this is deeply moving, but for some reason my microphone's not working!"

TATIANA PROWELL: That's the universe telling you that's the end of that show. That's—that's it.

MOLLY: Wow.

TATIANA PROWELL: Yeah. It's a lot.

MOLLY: I so appreciate you. Thank you.

TATIANA PROWELL: Well, likewise.

MOLLY: I definitely want you to get back to saving peoples' lives, though. [laughs]

TATIANA PROWELL: Thanks.

MOLLY: Wow.

TATIANA PROWELL: I've gotten all these texts while we've been talking, actually. I was just looking. I just had another person while we've been—while you called me back. [phone ringing] Oh whoops. Oh, sorry. Actually, hang on. This is actually Papa Doc's doctor. I have to go.

MOLLY: Okay! Go, go, go! Bye, bye, bye!

TATIANA PROWELL: Bye.

MOLLY: What a crazy experience.

JAD: We checked in with Tatiana after that conversation. Papa Doc had his transfusion on Wednesday night. As of Thursday night, when we finished this podcast, he was still in the ICU, still on a ventilator, hanging on. We will let you know more when we find it out.

ARTURO CASADEVALL: So I want to stress that there are a lot of people working on this right as we speak. And what I can—what I can tell you is that the current working criteria is that we are gonna wait two weeks, two weeks after the symptoms stop. Then at that point, you test them for the virus to make sure the virus is really gone. And then you ask them to donate blood, and then you look for antibodies from the blood. And those people with high antibody become donors.

JAD: If you have had COVID-19 and recovered and you'd like to donate plasma, go to our website, Radiolab.org. We've compiled a bunch of resources there for you. We tried to make it as clear as possible. You can go to the website of the American Red Cross, that's RedCrossBlood.org. RedCrossBlood.org. To find out more information there. If you're in New York City, check out New York Blood Center to figure out how to donate. Thank you for listening. Be safe out there. Special thanks in this episode to Evan Bloch and Dr. Tim Byun. I'm Jad Abumrad. Thank you all for listening. Stay safe. Keep taking care of each other.

[LISTENER: Hi. This is Jamie Acre calling from Woodland Park, New Jersey. Radiolab is created by Jad Abumrad with Robert Krulwich and produced by Soren Wheeler. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Suzie Lechtenberg is our executive producer. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Becca Bressler, Rachael Cusick, David Gebel, Bethel Habte, Tracie Hunte, Matt Kielty, Annie McEwen, Latif Nasser, Sarah Qari, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster. With help from Shima Oliaee with W. Harry Fortuna, Susan Sandbach, Malissa O'Donnell, Tad Davis and Russell Gragg. Our fact checker is Michelle Harris.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.