Mar 27, 2020

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

SOREN WHEELER: Cool. Do we have everybody?

JAD ABUMRAD: Okay.

MOLLY WEBSTER: I don't see Dylan.

SOREN: Oh, Dylan. Are you out there?

SARAH QARI: Oh, Latif.

ANNIE MCEWEN: We don't have Tad. Oh no, there's Tad.

SOREN: It does not feel like enough people. Our Brady Bunch doesn't feel bunchy enough.

SUZIE LECHTENBERG: No, it seems too small.

SOREN: Did Jad just disappear? Oh, Jad says his Audio Hijack short-circuited everything. There's—there's decay. I'm sure Jad'll be back in a sec. All right, well while we wait for Jad to log back on, just ...

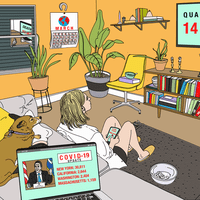

JAD: Hey, it's Jad. I am here. It's funny, like, at the beginning of all of this, I—I think we all felt a little robbed. Not we specifically, but I think all of us felt like we had all of these plans for our lives and now they had to be put on hold. But then as the sort of gravity of things has kind of set in, that feeling has thankfully given way to, I think just a lot of other feelings. Worry, anxiety, but also gratitude for the people that we get to worry about. Now there's been a lot of change here at Radiolab, even before this. Robert retired, we launched a whole series about Guantanamo Bay where Latif Nasser took the helm, and meanwhile we were preparing all of these stories that were gonna feature the rest of the team. And we were getting ready to say a thing, which I think you probably know, that over the years this show has shifted from being just about the two guys hosting it and talking to being really a collective of these incredibly talented producers and reporters. And we wanted to say that and show it, really, in the stories we were gonna put out. And then—and then this happened.

SOREN: And now did we lose Dylan, too?

JAD: And so, you know, every day, I guess like everybody it's all about Zoom, we get together at twelve o'clock, a giant Zoom meeting, and we ...

DYLAN KEEFE: Can we all do a common motion and make the grid, like, do fun things?

JAD: Kind of hang out a little bit in a Brady Bunch grid of video windows.

SOREN: You want to do a wave?

DAVID GEBEL: Yeah!

TRACIE HUNTE: Oh yeah, wait. But in my wave, David, I'm—I'm right next to you.

SOREN: We need lots of—a whole screen of jazz hands right now. Let's go for it. Yeah!

JAD: So partly, it's just about trying to keep some sense of community going. But also, it's about, like, trying to figure out what—what do we do for you right now? I mean, like, how do we balance the need to stare directly at this global crisis that's unfolding and report on it, while at the same time giving you moments where you can escape that? Which also feels important right now.

SOREN: I don't know. Like, obviously, like, things are changing for us in terms of, like, even how we think about stories or what stories to make.

JAD: Soren Wheeler.

SOREN: I mean, first things first, partly just so we can share with each other because we care about each other, but also maybe as fodder for, like, what's in our heads right now. Like, I remember—I remember, like—I remember talking to David a little bit about, like, you're just like, suddenly you just have this window to look out on.

DAVID: Mm-hmm.

SOREN: Like, what are the possible things that could, like—that could ...

DAVID: Yeah. And I have one—I have one tree in front of me.

JAD: David Gebel.

DAVID: I did a different angle today. And one is blooming and covered with blossoms and one is not. I don't know why. And then I did wonder whether there's a blossom for every single bud, or do they all make it? I don't know. I don't know enough botany.

SUZIE: I'm thinking a lot about people that are on the frontlines that have to go to work.

JAD: Suzie Lechtenberg.

SUZIE: That can't stay home. My sister's an ER doctor, and just thinking about the increase of patients coming in and then, like, thinking to myself that I have no idea how many patients come in on a regular day versus a day like now, and what that level of stress, like how that goes up based on the more people that are coming in.

LATIF NASSER: So much of the—so much of the coverage, like, is ...

JAD: Latif Nasser.

LATIF: For good reasons is, like, about these, like, life-and-death human stories, but I just, like, find myself wondering about all these objects. Like, you have the masks or you have the—like, the toilet paper and the supply chain. Or, like, I also wonder, like, a lot about the virus itself. Like—like, from its perspective. Like, is it alive? What does it want? Like, what is its internal monologue, like, right now?

SIMON ADLER: Totally unrelated to all the important things people are saying.

JAD: Simon Adler.

SIMON: I had to put in a press request with Corona. The—the beer company.

LATIF: Did you get any response?

SIMON: Not yet.

SOREN: They might be busy thinking of a new name, yeah.

- HARRY FORTUNA: One thing I keep thinking about is Ring Around the Rosie.

JAD: W. Harry Fortuna.

HARRY: How we got that from the Black Plague and how ...

ANNIE: I've been talking to my parents a lot.

JAD: Annie McEwen.

ANNIE: And my dad's like, "Man, I'm just, like, logging onto Wikipedia every day checking out that corona page. So interesting, see all the numbers, all the different countries, like, moving up and down, you know? Like, first Taiwan was doing well, but then, like, South Korea's really pulling ahead." And I was like, "Dad, you're only doing this because the NHL is canceled and you are, like, going through stats withdrawal." And so he's like, "Oh, man. Like, Italy is struggling, it's falling behind. But, like, I'm so—" he's like—and mom's like, "Yeah, he's checking it every single day."

SOREN: Like his way of talking sounds like hockey talk?

ANNIE: Yeah!

JAD: A bunch of stuff is coming out of these meetings, and we're putting feelers out in a lot of different directions while at the same time doubling down on some bigger projects that we already had in motion. But in the next week or so I want to put out a couple of short dispatches of stuff that's been bubbling up at these meetings, that we're all sort of learning about and reporting out as we're siloed away in our separate closets. And just to start with this particular Zoom meeting ...

MOLLY: I do keep thinking about, like, Annie's dad. I do keep thinking about numbers in, like ...

JAD: That's Molly Webster.

MOLLY: At some level, like, I'm sort of obsessed with all the numbers that are, like, coming out every day. Then they terrify me and then I don't understand how to understand them. Like ...

JAD: One of the things that just kept coming up was what do we do with all of the numbers that are swirling around this pandemic?

SARAH: The number I'm thinking about is, like, six.

JAD: Sarah Qari.

SARAH: The six feet, like, social distancing rule. Like, okay, like, can I go see my friend and, like, stand six feet away from them and that's okay? Like, even if in theory if one of us was carrying the virus? Like, would that be fine?

BECCA BRESSLER: I'm just wondering how the hell Facebook just donated 720,000 masks to the government. I'm like, "Okay."

JAD: Becca Bressler.

MATT KIELTY: What, they just had them in a closet somewhere?

BECCA: Yeah, they had a stockpile of them that they just forked over to the government.

JAD: Yeah, so in this Zoom meeting there's a lot of talk about these numbers, these public health numbers, economic impact numbers, and how do we process them, how do we understand them, how do we wrap our heads around them? And we might go deeper on some of this stuff in future weeks, but for the moment I just want to pull out two number-focused riffs from two different producers that happened organically in the meeting. But in both cases I called them up after the meeting and we talked a little bit more.

JAD: Okay, here we are.

SOREN: Yeah.

JAD: First up, Soren Wheeler.

JAD: I don't know quite how to prompt you with this, because I—I just kind of want to pull the string and ...

SOREN: Yeah, I don't know. I mean, I don't know how to prompt me with this either. I mean, like, it's that nerd part of me that I don't talk about very much that used to actually like math.

JAD: Oh, we all see it.

SOREN: And sometimes still does. Although I always kind of, like, pretend to not. But I don't know, somehow, I mean, I'll say that I ran across—one of the first things that happened is that I ran across this set of numbers that CNN had published, and it was like on March 1st there was this many cases, March 2, this many. Blah, blah, blah, down the line.

JAD: Yeah.

SOREN: The number's doubling like every two or three days.

JAD: Right.

SOREN: And I think then I was like, "Oh, right. Because of course, because everything in the news has been this is an exponential curve." Like, there's that word throwing around, "exponential," which I sort of know but I hadn't thought about much, and then I looked at this and I'm like, "Oh, it's doubling every two days." And I was like, "That's right! This is this thing that like, I think people really don't absorb what that means." I mean, they're sort of like, "Oh, exponential growth." Like, but I don't think, like, you know, the sort of visceral sense of what that—what it can do ...

JAD: Yeah. Yeah, it's funny. It's like I don't actually ...

SOREN: When it comes across.

JAD: What do I think of? I just think it's growing fast.

SOREN: I just think like it's growing more and more and more. Like, so like let me—and I remembered this old—and my dad was, like, a physicist and he was like a super, like, teach the world about—you know, he wanted, like, everybody in the world to understand, be literate in, like, math and science. So he—he would say things to me like, "Okay, I want you to mow the lawn every day for the next month.

JAD: Okay.

SOREN: "And I'll either give you a million dollars to do that, or I'll give you a penny today and then I'll give you two pennies tomorrow and then I'll give you four pennies the next day. We're going to do this for a month." I mean, like, I don't know.

JAD: Oh, so it was a choice between, like, a million dollars now ...

SOREN: Yeah, he's like, "You could either have this or that." Right.

JAD: In my soul, I'm like a million dollars. Give me a million dollars. Yeah.

SOREN: Yeah, exactly. Exactly. So the—so if you do the pennies, you end up pretty close to $20-million by the end of the month.

JAD: Whoa! Wow!

SOREN: Starting with a penny. And the—and this is the thing about this curve is like, halfway through the month you're like, "I've got 50 bucks," or whatever. But it's the last two days of the month where it's like, kabam!

JAD: Interesting. Well, when you were a young boy and your dad was telling you this, like, did it make any kind of sense to you?

SOREN: I mean, I think at that point—and maybe still now, it just like made me always, like, one, always—whenever anybody says anything about doubling pennies take that one.

JAD: [laughs]

SOREN: You know? It just gave me a trick for dealing with the world, which is to say I knew then that this thing that seems like not a big deal could be a big deal. And I just used—you know, like, I just—it's not like I intuitively understood exponential curves from then on, but I just knew that things turn out bigger than you think. Like, way bigger than you think. And so that was the feeling I got when I was looking at the CNN numbers. Like, "Oh, this is the penny thing. This is gonna go like that."

JAD: Hmm.

SOREN: Or it could go like that, really if we don't—you know, like, there's a whole big thing here about we step in, we can change this. So I started thinking about, like, how—like, my main thing is, like, I don't think people get this. And even after I talk for a while I don't think people get it. What they get if they're—the only thing you really get is like I got when I was a kid, which was like, look out, or be worried, or this is tricky, you know?

JAD: Yeah. Yeah.

SOREN: But you don't actually—you know? So I started thinking like, "Oh, are there things you could do to actually feel it?"

JAD: Yeah, like feel it in your bones.

SOREN: So I was thinking, like, I—you know, I work in this little shed that I built in my backyard in Wisconsin.

JAD: Yep.

SOREN: Where I've quarantined myself. Not—I don't mean that quite literally, but it's 10' by 10' or so.

JAD: It's like the size of a rich person's bathroom.

SOREN: Yeah, you would—this would—wow. Now I'm looking around, like yeah, this would be a luxurious bathroom. But it does not feel like a luxurious office. I mean its 10' by 10', it's not that much.

JAD: No. It's slightly bigger than a cubicle, basically.

SOREN: Yeah. But anyway, this is my little office. It's nice because it's 100 square feet. It's an easy bit of number to deal with. So I'm like, "Oh, what if I was just doubling the size of my office every day?" We'll do the same thing with the pennies. Like, every day for a month, right? Today it's 100, tomorrow it's 200, third day of the month it's 400, 800, all that. But like, the fifth day of the month it's about the size of my house. I think by day 12, it's, like, an average city block.

JAD: Whoa.

SOREN: At the end of the month, it's New Jersey.

JAD: Wow!

SOREN: Yeah.

JAD: Dang.

SOREN: Actually, wait. No, I think day 32. It's the first day of the next month, it's Jersey. But whatever. But, you know, the weird thing is that, like, for most of the month I was like, "Yeah, it's getting big." But then all of a sudden you're just at Jersey. And, like, if you go, like—go a couple more days, let's go into the next month. By the 10th day of the next month, you're bigger than the United States. And by the, let's see—is it the 13th, 14th of the next month? Maybe the 15th? It's the surface area of the Earth. So ...

JAD: Whoa. A month gets you half ...

SOREN: So a month gets you to Jersey. And another half month gets you to the Earth. And then also I just kept thinking about, like, what are all the different ways that you could—that you could do this to almost, like, literally sense the curve? Like, you know, could I do it with touch? And I tried that with air pressure but it got weird and it didn't really work. And then I was like, "Oh! I mean, we could do it—we could do it sonically, right?" I don't know. Music is frequencies, right? We can hear 20 hertz. That's as low as we can go as humans. And we can hear up to about 20k hertz.

JAD: Right.

SOREN: So 20,000 hertz. And so if you did—you just doubled that once a second, 20 hertz, 40 hertz, 80 hertz, you just go smooth up.

[frequencies going up in pitch]

SOREN: It's about 10 seconds or so before you're out of hearing range.

JAD: Okay.

SOREN: I don't know how impressive that is, but maybe more—more immediate than that is like—and the thing that everybody has experienced is, like, feedback ...

[feedback]

SOREN: ... with a microphone and a speaker. Like, when the speaker comes up to speak, like that horrible, awful—everybody goes, "Ow!" That's an exponential growth situation.

JAD: I mean, you're right. It's like, if you're feeding the speaker back through the mic and into the speaker, then the speaker has doubled and then it's being doubled again and then it's being doubled again.

SOREN: Right.

JAD: It's exactly like the penny, but in sound.

[feedback]

SOREN: Right.

JAD: But you know the interesting—the fun thing to do with feedback, which I've done many times is you can slowly move the mic back from the speakers.

[feedback]

JAD: And modulate how much ...

SOREN: Exactly my friend. You flatten the curve.

JAD: You flatten the curve, so you ...

SOREN: That's literally what you're doing with feedback when you want to mess with it and put it on the edge of musicality instead of just ear-splitting annoyance, is you flatten the curve. That's—like, you are sitting in your studio right now not shaking hands with people on the street is that.

[feedback]

JAD: You know, it's like the thing I keep wrestling with pretty much every time Cuomo opens his mouth and he says these numbers. Things like we will very much—we will very likely see 100,000 cases within X weeks or whatever it is. I mean, they make these numbers which seem, compared to the moment, astronomical.

SOREN: Right.

JAD: And ...

SOREN: And so you sort of seem like, "Oh, man. They must be talking worst-case scenario or they're just trying to scare us."

JAD: Yeah and it's like, hearing you go through these exercises it makes me think, maybe we're only on day eight or nine of the growth. And so they're already looking mathematically at day 20 and then day 40.

SOREN: I mean, it all depends exactly what number you start with. And honestly, the totally messed up thing is it doesn't even matter. Like, I could list the numbers I saw on CNN but they're irrelevant because they're just cases that have been tested. We don't really know the total number of cases.

JAD: Yeah.

SOREN: But regardless of all that, they're all following this kind of curve.

JAD: Yeah.

SOREN: And then, like, what I think about is like, if my shed just started growing, doubling every day, and I was sort of like, "Uh, hey everybody? This thing seems to be growing, and I'm kind of worried about it." And if I just went out there, it's like—what was it? What did I say? On day eight—day five, it's the size of my house and who even cares about whether it took over my house or not. And I'm going, "Yeah, but I did the math and in about 40 days it's gonna be the whole Earth." [laughs] People are gonna be like, "What are you talking about dude? The thing is the size of your house." I'm like, "Yeah, but 40 days from now it's gonna—my shed is gonna be the whole Earth and everybody's—you know, like, it's just ridiculous to try to be a—to try to communicate that. And so the question is like—I think about a lot and maybe scientists are thinking about this too, when—when should I talk? At a time when it's not too late to do something about it, but people won't think I'm saying the sky is falling.

JAD: When will you be able to say it in a way where people will get it and not think you're crazy?

SOREN: Yeah. Yeah. And you don't—really don't—and also, you want to take the math pretty far out to just be like, "This is what happens." But on the other hand, our responses are real, and China has flattened the curve and South Korea has flattened the curve and, you know, it's not gonna go the distance of, like, all these crazy things that I was saying about covering the Earth or whatever because we can flatten it. But not unless we know—we act like we know what this thing is.

JAD: We'll be back after a quick break.

[LISTENER: This is Kaitlyn Bissell calling from Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. For more information about Sloan at www.sloan.org]

JAD: This is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad.

TRACIE: The number that I keep thinking about is just the fatality rate. You know, whether it's one percent or is it gonna be, like, four percent? And you know ...

JAD: Tracie Hunte.

PAT WALTERS: Thinking about all the people losing their jobs a lot.

JAD: Pat Walters.

PAT: 22 people here and 500 people there and 600 people here. And there's, like, projections of three million by June.

RACHAEL CUSICK: With numbers in general, like, I kind of feel like ...

JAD: Rachael Cusick.

RACHAEL: ... I personally, like, short-circuit when I hear a number, like if it's a death or something, because it just, like, loses all of the depth and, like, hues of what's going on. So I feel like I'm numb to numbers.

MOLLY: All right. Great.

JAD: Second riff, extended riff, comes from Molly Webster.

MOLLY: Yes, that is going. You're going. We're all going.

JAD: Yeah, we are so going.

MOLLY: We're so going.

JAD: Do you want me to prompt you with what I remember of what you were saying?

MOLLY: I don't—I mean, I know what we both remember. We remember that I keep thinking about, like, what does it mean to wake up with numbers flashing at us, and like a ticker tape of coronavirus, like, curling on every digital screen that I'm looking at every day, like, beating a drumbeat of like, "This is a thing that's happening." There's something about just, like, seeing headlines where it's like, "400 more people got this overnight," and then the next day it's like, "523 people got this overnight," and it's like largest caseload yet. And then it's like, "21,000 people have it in the United States." And it's just this state that we're in right now, but I also think about because numbers carry such weight, I keep wondering about, like, the psychological effects of that drumbeat every day. I just wonder what it would be like if—if all of the time in our lives we had numbers just assaulting us repeatedly every day. And the first thing I thought about was the flu, and knowing that, you know, at least at this point in time that we're talking, there are more cases of the flu and more deaths from the flu than from coronavirus.

JAD: Is that this year? Or is that in general?

MOLLY: I mean, that would be this flu season. So it would be, you know, the end of 2019 to now.

JAD: Really? So there's been more flu deaths from non-COVID-19-related flus than from this one?

MOLLY: Yes.

JAD: I did not know that.

MOLLY: And like—and just like, thinking about like, what if I woke up every day and they told me, like, how many people went to the hospital with the flu? Or like, how many people died because of the flu. Like—and then so I just kind of started poking around, like, just to see. And it was like, this week for the flu, you know, they're still counting the death toll, but it's like, 347 people died, which is, like, 49 deaths per day. The week before that, 487 people died ...

JAD: Wow! Of ...

MOLLY: ... of the flu.

JAD: And this is no COVID involved at all?

MOLLY: No, these are just—this is just the flu. And there's so many things that's wrong—that are wrong with this metaphor. Overall, coronavirus has a higher death-rate than the flu, so we just aren't there yet.

JAD: Right. Right.

MOLLY: Essentially. Like, if the death-rate plays out, it will be higher. But it's not really about, like, the direct comparison, it's just like, what would my emotional reaction to, like, the flu be, if every morning I woke up and they told me how many people died of the flu?

JAD: Yeah. And it's like in 28-point font right there on the front page.

MOLLY: Yes. Yeah, and it's, like, this interesting thing where—where I'm, like, dancing this fine line where it's like, coronavirus is scary, we should all pay attention to it, it is worse than the flu. But at the same time, like, I just think about, like, what it's doing to me, like, emotionally, and to the rest of the country, and to, like, the world, to have this, like, ticker tape going off, you know?

JAD: Yeah.

MOLLY: That is—that is in a 24-hour news cycle literally updated, how many times a day? Like, every hour.

JAD: Yeah. I mean, it's like when I talked to you last time, you were like "Oh my God, can I handle more numbers? There's too many numbers coming at me right now!"

MOLLY: Well, it was—there were so many numbers, and it is like you start getting lost in it where you're like, "Oh, should I care about the hospitalization rate? Or should I care about the death rate, or should I care about how many people are getting sick? And I guess I care about all of them." And then all of a sudden, I'm like "Wait, do I know what the latest numbers are? And, like, how many people have them?" And then I'm like, "Is there really a difference between 400 and 5—like, for me?" And there is. It's bigger, it's 100 bigger, you know? I don't know. I don't know. I probably need to know that. Because you're just like, "Okay, I and/or people I know are gonna get coronavirus. Good chance someone I know will probably die from it."

JAD: Yeah.

MOLLY: And so I'm not trying to be, like, trite.

JAD: Sure, sure.

MOLLY: This is a super serious thing. I guess I just wonder though, like, would I take cancer more seriously if, like, every day there was a thing on the front page of the New York Times that said like, "1,600 people died yesterday from all cancer?" Like, that is a real thing that's happening.

JAD: Wow. Yeah, if we took the amount of intensity and anxiety that's—that these numbers are generating and actually transposed it onto cancer, how would we, how would that ...

MOLLY: Well it's like suddenly would we actually care about cancer and, like, be super-conscious of it and trying in 18 months to find a cure, you know? It's like—like, I was looking at the CDC websites and, like, different, like, health websites just to stay in, like, medicine-land for a little, though my brain has gone many places with this. You know, basically it's like, 890 cases of breast cancer will be diagnosed each day in 2020. And so like, what if every morning I woke up and it was like, "890 women were diagnosed with breast cancer." Or like, "9,500 people they think will be diagnosed with skin cancer each day."

JAD: Wow.

MOLLY: You know, and then it's like, oh, will I suddenly start wearing sunscreen?

JAD: Hmm.

MOLLY: What would it be like to live in a world where every day they told me how many polar bears died?

JAD: Roughly two a day, 666 a year.

MOLLY: Or, like, how many flowers bloomed? Because that's, like, happier than all the bad stuff. Like, it doesn't have to be ...

JAD: Yeah, I was like, "Go there, go there!"

MOLLY: It doesn't have to be bad things.

JAD: Trees blooming on the first day of spring, roughly 1.5 billion trees flowering first day of spring.

MOLLY: Like what if every day I had a ticker tape of, like, how many jars of peanut butter had been sold, you know?

JAD: How many jars of peanut—do you know that number?

MOLLY: Wait.

JAD: Knowing you, you probably know that number.

MOLLY: I do. I do know that number. It's two hundred—this is the estimate: 246,575 per day of a single brand.

JAD: Wow. That's ...

MOLLY: Or like, what if there was, like, the number of babies born? Which is something like 360,000 per day at this point.

JAD: Wow, okay. That's like 1.2 babies per jar of peanut butter.

MOLLY: I know! [laughs]

JAD: Keep going!

MOLLY: 18 million Uber rides a day.

JAD: Wow.

MOLLY: That's worldwide.

JAD: That's insane.

MOLLY: There's like 172,800,000 gallons of wine drunk a day.

JAD: Wow!

MOLLY: Six million tons of garbage made each day.

JAD: Oh my God. If that were the number we saw in the papers everyday, we'd definitely want to bring that number down.

MOLLY: How many rocks were skipped on a lake?

JAD: Ballparking it? 102,614.

MOLLY: How many bonfires were made?

JAD: Maybe 32,017.

MOLLY: The number of baby seals that died? I don't know. I just saw a baby seal for, like, the first time a year ago. I think I like them.

JAD: [laughs] Who doesn't like a baby seal?

MOLLY: I don't know!

JAD: They're like little puppies.

MOLLY: I feel, like, a great affinity for them.

JAD: They're adorable!

MOLLY: And so I was like, "I wonder how many baby seals died?"

JAD: If you just look at harbor seal numbers, a few hundred thousand each year are lost each year to predators. Let's say 240,000. Divide that by 365. You get 667 lost day, which frankly seems like a huge number.

MOLLY: How many girls got their periods?

JAD: Roughly two million.

MOLLY: How many houses were built?

JAD: 1.6 million a year. That's a real number.

MOLLY: Or number of iPhones bought? How much bitcoin was made? How many people danced that day?

JAD: I mean that's a really good one, actually, right now. That one I want to hold—hold in my consciousness. The reason I really like this idea, a lot of the stuff you're playing with is, because for me there's a—there's a kind of myopia that sets in with these numbers. I mean, and for good reason. Like, this is absolutely serious. And it's happening. And we all need to pay attention to it, really focus on it. But it does remind me that when you do the peanut butters and you do the purple flowers, it just reminds me that, like, even in this intensely anxious moment, where we have this tendency to fixate on these horrible, ever-fluctuating numbers, we can though, through an act of will, remember that there are other stuff—there's other stuff happening in the world that we should—that's still worth paying attention to.

MOLLY: It's like perspective. Like, the onslaught for me has been really intense, so I've started only reading the news once a day. Like, I'm almost forcing the old system, like, of a newspaper lands on my doorstep in the morning.

JAD: Yeah.

MOLLY: Because it's just like—it's such an onslaught.

JAD: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.

MOLLY: I don't know. It's like I can't—I can't almost focus on anything else. And then today, I turned off my phone from, like, 11:30 to right before we talked and I went to the park. And then I came back and I, like, read and made dinner, and it was just like, oh, there's still a world out there.

JAD: Yeah.

MOLLY: Regard—like, this thing is coming. It's gonna blow through here. I don't know what it's gonna do to me and everyone I love and people I don't know but still love from afar. But there's still, like, a park and a flower and that person and their dog.

JAD: Totally. Yeah.

MOLLY: Just like life.

JAD: You know, the number that I—that's just occurring to me is the number 100. I think that number, 100 days, like the first 100 days comes from—from I believe from F.D.R., who in the wake of the 1929 crash, like, in a hundred days basically reformatted America, you know? I mean, you had all of these social safety programs coming in and passed one after another after another, because things were so, so dire at that moment that everybody just sort of stood in lockstep basically said, "This is the—this is the country we want, and let's just do it." I wonder what happens in the hundred days after this?

TRACIE: I see so many people were like—when you were talking were, like, shaking their head. "No, we're not gonna change. We're not gonna ..."

SIMON: Or, you know, we are but it's gonna change in—in a direction that's just opposite of F.D.R., ideologically. Like, you know, that everything will shift just, you know, away from social support and toward something else. More capitalism. It feels like a tipping point.

BECCA: Yeah, like, speeding up the future in a way, just because it's this—yeah.

SARAH: Oh my God, I just want to jump in and say I have a little bit of hope. I'm starting to get really, really depressed and I just need to say I feel like—no, I feel like this—there's a real—I think there's gonna be a lot of shitty outcomes, but it also feels like a real moment where could, like, take a deep breath and, like, reassess and, like, take forward, even as individuals, like, what do we want to take forward, like, from this time? Like, we're gonna see a lot of places in our lives where, like, things are lost, and we might actually be like—or things are changed, and you might actually be like, "Oh, that—maybe that change is okay."

PAT: I'm on Team Hope. I'll raise my hand for hope, too.

JAD: Yeah, I'll third that.

MOLLY: Wait, can I ask a technical question with everyone here? Or I'm gonna send an email, I can do either.

DYLAN: Let's—let's find—I do need to off—I need to bolt, so let's find a way to offline it and get an email out. But I can join you in the conversation or whatever to set the parameters you think make sense, but yeah, let's feed it back some other way. Okay, kids.

TRACIE: Thanks, everybody!

MOLLY: Jad, are we staying on? Oh, I guess not. Oh yeah, there you are!

JAD: Still here. Before we close, I just want to thank—you know, in Molly's riff, a lot of those numbers, especially some of the more guess-y ones, we had help from a professional guesstimator of sorts. Hat tip to physicist Larry Weinstein. And yeah, I guess that's it. I'm Jad Abumrad. Thank you guys for listening. I hope you're healthy and I hope you're coping. Please stay safe and stay inside. We'll have another dispatch for you in a couple days.

[LISTENER: This is Eddie calling from Hobart, Australia. Radiolab is created by Jad Abumrad with Robert Krulwich and produced by Soren Wheeler. Dylan Keefe is our Director of Sound Design. Suzie Lechtenberg is our Executive Producer. Our staff includes Simon Adler, Becca Bressler, Rachael Cusick, David Gebel, Bethel Habte, Tracie Hunte, Matt Kielty, Annie McEwen, Latif Nasser, Sarah Qari, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster. With help from Shima Oliaee, W. Harry Fortuna, Sarah Sandbach, Malissa O'Donnell, Tad Davis and Russell Gragg. Our fact-checker is Michelle Harris.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.