Dec 9, 2013

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab.

ROBERT: We're continuing with our live performance of Apocalyptical from the Paramount Theater in Seattle, Washington.

JAD: We just heard a new theory about the end of the dinosaurs, a very sudden, fast, dramatic end…

ROBERT: With a sudden, musical kaboom at the very, very end.

JAD: Now, for the next question.

JAD: This is sort of the obvious next question, which is, what made it through and how?

ROBERT: Well, we did ask scientists that question, and here is what they told us: If on that day you were a creature in the ocean and you happened to be within 300 feet of the water surface, so if you imagine this room filled with ocean water, we're talking about you guys up there in the balcony, up there it will not surprise you to learn you don't do very well, there's a certain amount of heat, and mostly there's acid rain pouring in so a lot of you will die, but down with the higher paying seats, if you're below 300 feet, and this always happens to people with—with the better—anyway—you do fine, and on land it turns out…

JAY MELOSH: Plain ordinary dirt is a very good insulator, if you've got 1200 degrees on the surface then about 3 or 4 inches down you'd be comfortable there for several hours…

ROBERT: Oh.

JAD: Oh. Just a couple inches.

JAY MELOSH: You only need a few inches.

ROBERT: So that means you could be a little worm, and if you squiggle down, you're ok. You could be a beetle, squiggling down, you're ok, you could be a dinosaur tending to an underground nest, and if the nest is far enough below the ground, and a lot of them were, then the babies that hatch will will have babies that hatch that have babies that hatch, we will call their babies years later Birds, and if you're an early version of a crocodile and you bury yourself deep enough into the mud you also get through, as do the plants, roots, a lot gets through actually.

JAD: And that actually brings us to what I find to be one of the coolest parts of the story, this is the part that involves all of us in this room, so it turns out on that day as the fire was raging above on the surface somewhere in a little hole on the ground happened to be a furry little animal that has the distinction of being the great, great, great, great…

ROBERT: Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great. Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: [Chanting rhythmically] Great. Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great. Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great. Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great. Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great. Great.

JAD: Great.

ROBERT: Great.

JAD: Great. Great. Etc. grandma of everybody in this room, it's true. There was a creature down there [laughing] there was a creature down there…

[audience claps]

ROBERT: I thought we should stop there because we were getting away with something and I didn't want to push it too far.

JAD: All of a sudden it was just you and me.

ROBERT: Yeah I know.

JAD: There was a creature down there in—in a little hole, and when the dinosaurs got cleared away this creature could step out of her hole, she could step out of her niche, she had more food, more places to roam, she could populate the planet ushering in the age of mammals and now here we all are in Seattle.

ROBERT: Oh, don't flatter yourself. It's not a straight line.

JAD: It's a wiggly line.

ROBERT: It's a wiggly line.

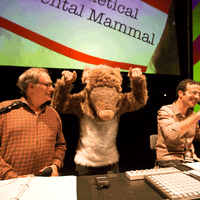

JAD: But here's the problem. We've never known anything about this animal that gave rise to all of us, we've never known what she looked like, we've never known, you know, how she spent her days, we've never known anything, because we've had no fossils of her. But recently, actually literally as we were reporting the story, right in the middle of our reporting, right in the middle of our reporting, a team of scientists led by a woman named Maureen O'leary, who is herself a mammal, she took fossils that we do have, fossils of this creature's descendents and then using fancy algorithms was able to cross reference the traits to work her way back for the first time to a composite picture of what we think our great, great grandma looked like, so now, Seattle a radiolab exclusive, we present to you our great, great, great, great etc. Grandma.

JAD: Here a giant rodent costumed thing runs out onto the stage…

ROBERT: All right, well this is what she looks like and we ought to point out certain anatomical features that caught the scientists admiration, first of all she has very, very pink and fleshy ears, so show them that, and a pale, soft underbelly, which, oh has very nice fur as Jad is now demonstrating, could you show them your profile just so they can see your head, her skull is considered either rat-like or crocodilian you can go either way but she does have enormous beady black eyes, a fleshy pink nose, and would you show them your teeth, she's kind of proud of them because they can tear flesh, and they can rip lettuce, she is an omnivore.

JAD: However, here is the issue, here is the issue we ran into. When we asked Maureen the scientist who did this work, we were like okay we've got an image of this creature that's amazing, what do we call her. What is her name? This was Maureen's response.

MAUREEN O'LEARY: Its official name is The Hypothetical, Placental Mammal.

ROBERT: [blows a raspberry sound] What kind of name is that?

JAD: I'm suddenly feeling bad for this little creature.

MAUREEN O'LEARY: Well, it's not something that we thought of as we were, sort of, busily working on the paper.

ROBERT: But then a funny thing happened. Our producer Molly was talking to Maureen and she said, "Gee, this is such an awful name.”

JAD: Maureen says to Molly, "Well, you could name it.”

ROBERT: And Molly says to Maureen, "Wait, are you serious?”

JAD: Maureen says to Molly, "I don't know. Are you serious?” So, we're like hell yeah we're serious. Let's crowdsource this. Right? This is what mammals do these days, we crowdsource. I mean, think of this opportunity, a little radioshow gets to name the ancestor of us all, so we put the call out to the internet, we got 1,000 submissions in response. Great names like Placentor…

ROBERT: Placentor!

JAD: Furst.

ROBERT: Furst!

JAD: F-U-R-S-T. Nova!

ROBERT: N-O-V-A.

JAD: And after eight rounds of voting the winning name was…wait for it. Wait for it. Wait for it.

JAD: On the screen you see the following letters appear, one after another: S-C-H-R-E-W-D-I-N-G-E-R.

JAD: Schrewdinger! Schrewdinger! I can't even tell you what a crisis this was for the staff. This was such a bad day. And the whole experience made us wonder, should we have died in that asteroid? Do we deserve to be here?

ROBERT: So, if you're asking yourself what is the moral of our story here's what we've shown you. We have a big, mighty species that died and then a smaller species which is you and I, we take its place. So you've got death and you've got resurrection and you got it maybe in a single afternoon, so that's the argument we're making here. This is Jay Melosh's argument that it was boom, over.

JAD: I mean it's the sudden-ness of the whole over, that is kind of unimaginable. I mean like, there you are one day, you have evolved over millions of years to be this long-necked beautiful creature 70 feet from your nose to your ass. And then…

ROBERT: Tail.

JAD: Or tail. And then in an afternoon, like on one Tuesday afternoon suddenly you, everyone you knew—gone.

ROBERT: Yeah, but there are other ways to think about this. The extinction, yes, was sudden. But in the grand sweep of time it wasn't really an end. It was just a moment in a stream of endless change. Because everything we see around us, the tallest mountains, the size of oceans, the animals about us that seem so different from ourselves, every category that we have in our heads that seems so permanent blurs given enough time. Mountains erode and become hills, then beaches. Animals change in any—all kinds of ways. The only thing that's constant, that's always, is change. We like to think of ourselves, we humans, as somehow inevitable, or crucial, pivotal. That the past was a time when we were missing and the future will always have us in it. But that's an illusion says this great science writer Lauren Isley. "We are rag dolls made of many ages and skins,” he says, "changelings who slept in wood nests or hissed in the uncouth guise of waddling amphibians. We've played such roles for infinitely longer ages than we have been men. Our identity is a dream. We are process, not reality.” What we call reality, says Isley, "is an illusion of the daylight, the light of our own particular day.”

JAD: Just a couple of notes before we go on. That whole dinosaur thing about the sudden, fast end, that is just a theory. Verdict is obviously still out. In fact, in 2011 a team of scientists published a paper that maybe the asteroid that hit the earth creating that devastation was not Baptistina, but another asteroid with a different name. But with the same size, dimensions and all that. So, who knows.

ROBERT: Also, when I said to the people up in the balcony if you were in the balcony you might have been killed off by heat I think that turned out to be a little bit wrong, if you had been in the shallow ocean on that day it would have been acid rain and some other factors that would've done you in, not so much the heat.

JAD: Okay, so this is the part of the show coming up where we—we—well we traveled with a bunch of different comedians, Patton Oswald, Simon Amstell, Ophira Isenberg, Kurt Braunohler actually Kurt opened this particular show, you can see his full set at Radiolab.org. Super funny. But on this night we had two comedians, and so, right at this spot in the middle of the show, out walks a guy, one of the most talented mammals…

ROBERT: He looks like actually, it's like someone with a finger in an electric socket, huge amounts of hair that are standing like out, like he's got a halo…

JAD: His name…

JAD: Reggie Watts!

JAD: We're just gonna play his whole set. It's a little Seattle specific in spots but, it's just—well.

REGGIE WATTS: Hello. Hello. Hello. Hello. Hola. [speaking spanish] Microsoft. Um.

[crowd cheers]

REGGIE WATTS: Thank you. This is a—this is a moment that you have to take if you can, and if you can't, you know, then you've lost it. But, once you have it, once you possess the moment, you can do so many things with it. A lot of people tend to just exist within it, others pawn it off to moment brokers, or if you're a big fan of moment chance, you can do that. Also, the Moment, Moment Glory blend of coffee single origin from Argentina is excellent, you can get that at most Bauhaus or participating some town coffee roasters, so definitely check that out. Really stoked that we finally closed down that awful Bauhaus coffee and books. It was just—what a terrible location, right? You know, right on like the corner where you can see it really visibly. And, I—I don't like that. And—and I called the city—the city comptroller and I just said, ”We need to get rid of it.” And we need to get as—rid of many, many buildings, ‘cause a lot of those buildings are so old, up on Capitol Hill, it's just, it gets—it gets old, and so, I'd like to replace them with new constructions. Mostly glass, some contemporary metal, and I want to be able to see the architects idea and then see them have to shave off about 40% of that idea by replacing a lot of the materials with cheaper versions of the original design, I enjoy seeing that, and I would rather see that than a coffee shop that promotes a type of communal living that can only happen in an area that it is located in, I just prefer it, that's what I prefer. That's just me, sorry guys. I love new buildings. [laughs]

REGGIE WATTS: Okay. More, more, more. Okay. So. Obviously as you know, Seattle is becoming Vancouver and—and the thing is, like, I'm gonna do a song that is about that so you guys can get a little bit more used to the Vancouver culture that is spreading down Cana-da. Canada. Little Mr. Rogers reference but Canada is the land of make believe. Okay. Here we go. Okay. Okay. Here we go. Any big fans—anybody born after 1990? Okay, that's about the tonality you'd expect. Why is it always higher? I don't understand that? Okay, anyways, so you're gonna know this reference, this is from the old Buck Rogers series. Biggie, biggie, biggie. Gee buck. You know. That kind of stuff. So that's for you guys after 1990 so you guys can relate to what I'm doing on stage. And so, I hope you like this. This is definitely, definitely a song. [beatboxing, singing]

[Crowd cheers]

REGGIE WATTS: Thank you. Thank you. Thank you very much. If you're—if you're down at—in—in Ballard, having a good time, it's—it's because there's so much Scandinavian energy there that they just—they just do it right. So, if you're at the Sunset Tavern and you're like, "Why isn't this turned into a glass tower?” It's because the power of Norway. There's Nor-way, they're gonna screw with that. You know what I mean? Like, Nor-way at all. Know what I'm saying? There's Nor-way out of this. I mean if you're basically—you know what I'm saying? It's like a hot dog, you know? You—you think you want it and you're like, "I don't…” Probably not. But—and I'm pretty stoked, I've said this before, but I am gonna say it again, just ‘cause we're in Seattle, but I am pretty stoked about a Vivachi being replaced by a Starbucks. I just think that it makes sense, it makes sense. Let the people who do it really well do it better. You know what I'm saying? That's what I'm sayin'. So, this song is gonna be one of those songs where you're going to think to yourself, "Is this better than the original?” Maybe. Okay. Allright. It's called Pastiche in Lieu of Originality. Here we go.

[Beatboxing, singing]

REGGIE WATTS: You know what, the thing is—the thing is, I think using—using—using—using logic, I think, you know, obviously it is smart to name a company after a character from Battlestar Galactica but I just don't—it makes sense. And that's why I'm starting my own coffee business called Cylons. Cylons coffee is the best coffee. I have a new movie coming out called Cylons of the Lambs and it's a theme song, it's done by Garfunkel and Oates, course you can probably guess what that song is called, the sound of Cylons, which is just [mouths robotic Cylon sounds] and sometimes [Cylon sounds] and sometimes [Cylon sounds] that's the sound of Cylons. Okay, so this song—thank you. For my next trick. No, it's been a pleasure. This is my last Radi-qiolab, and I am in all—no in all seriousness, that's a totally different show. But, Radiolab, it's been awesome man. I mean, I discovered some really great friends the first time I did something for Radiolab and continue to find great friendships and love and passion for sound and science, knowledge are art, and so I think that I'm lucky to be a part of it in the small way that I am so thanks Radiolab, wherever you are. Okay, so this is a—this is a quick song, it goes… [beatboxing] Okay. And this song is, this is a good one. Okay, here we go. [singing, beatboxing]

REGGIE WATTS: Thank you so much, guys. Thanks Radiolab.

[audience cheers]

JAD: Give it up one more time for Reggie Watts!

JAD: Let's just take stock for a second, Robert, we did our super fast radical dino ending, Reggie did his Reggie ending…

ROBERT: Which—which, you're never quite sure what he's saying, you know. Can you imagine, we have scripts and everything, imagine if I just went to you [imitates Reggie Watts singing] all evening long…

JAD: It would be outer space, man.

ROBERT: I know. Well.

JAD: Okay, so what's next. What's our next ending?

ROBERT: We're gonna—we're ready for the pink ending now.

JAD: The pink, you mean like the color?

ROBERT: Well, yeah. This is the one that asks I think the most basic question you could ask in a show in a show like this, this asks when did endings begin? It's a serious question.

JAD: That's a weird one, when did endings begin? Wouldn't—there always, I mean the moment you had beginnings wouldn't that then imply an end, because the beginnings then have to do something: end.

ROBERT: You'd think so, but if you think hard about the origin of the universe I would propose that when the universe began, which by some interpretation was a huge explosion of energy which then condensed and cooled into matter, that that whole event came in without any notion of endings at all. When you get matter, when you get that condensation you get a list of elements which we can now turn to in the periodic table of elements with which you I'm sure are very familiar and enjoy every evening before dining or sleeping.

ROBERT: Keith here now puts the periodic table up on the screen.

ROBERT: So, if we, if we look at this chart and we start on the upper left hand side with hydrogen and we move through it to Helium and Lithium and Beryllium, Boron and Carbon and on and on, as we move through the list I can tell you that every one of the first 82 elements on this chart, with two exceptions which I'll mention in a moment, every one of these has a version of itself that goes on forever and ever and ever until the end of time.

JAD: Every one of these, you're saying, is immortal? Is that what you're saying?

ROBERT: Yes. Now, here's the thing, and when we get to number 83, Bi, that's Bismuth, I would argue that this is where the universe invents endings.

JAD: Really, what is—what is bismuth?

ROBERT: It's a rock, kind of a shiny black rock.

JAD: And you're saying this shiny black rock is—is—is—is where death begins?

ROBERT: Yes. Yes, I would say that. That's a fair…

JAD: Why would that be?

ROBERT: Well, because all atoms at the bottom of this chart are a little heavier than the ones at the top, meaning they have lots and lots of neutrons and protons.

JAD: Here Keith brings up an image of a bismuth atom, with lots of jiggling protons and neutrons.

ROBERT: There's so many of them as you can see they're having a little trouble holding their—themselves together, and French scientists studying this atom recently determined that inevitably, inevitably something will happen to this atom, it goes something like this.

JAD: Protons and neutrons fly off the atom, and amazingly Robert's [pew] was perfectly timed in this case with Keith hitting the button to do it visually, and that had never happened before.

ROBERT: Woah. I—...

JAD: You timed that so well.

ROBERT: Okay, I don't know if I can do it twice. Woah, you don't add sound effects, I do the sound effects and you do the—one more time. Oh, now you're like— go on strike.

JAD: You've made him angry.

ROBERT: Stop it.

[audience laughs]

ROBERT: The point I'm trying to make Keith is that this atom when it loses protons it loses its identity, when an atom decays this atom is no longer a Bismuth if it doesn't have the right number of protons, that's the way chemistry works.

JAD: So, you're saying, like, as it—as it sheds its protons and neutrons it's dying?

ROBERT: That's right. Now, here's the cool thing, when we go back to the chart, to number 83, every element after it…

ROBERT: Elements 84 to 118…

ROBERT: Also, decay.

JAD: So, on the periodic table you see two teams basically, the ones at the top they're forever-ers…

ROBERT: They go forever.

JAD: And on the bottom you have the ones that die.

ROBERT: Right.

ROBERT: That's correct, that's correct, with the two exceptions I mentioned, I should say. 43, and 61, that's Technetium and Promethium, nobody really likes those two.

[audience laughs]

ROBERT: They're—I find them actually unnecessary.

JAD: I tell you what if they—if they mess up the logic here let's just—let's just get rid of them.

ROBERT: Let's get rid of them.

JAD: Get them out of here.

JAD: We just poked two holes into the table.

ROBERT: Let me just say, when we divide it up like this now you can see that Bismuth is apa-dividing my mibi of the universe cause this is like, this is where you see, it's like the KT boundary with the dinosaurs, but this is the—this is the…

JAD: For everything.

ROBERT: For everything. But the cool thing is bismuth is pretty good for you…

JAD: Really?

ROBERT: Like, people swallow little bits of bismuth that get tummy aches that do this all the time, you recognize this color, maybe?

JAD: The screen fills with pink.

ROBERT: The pink I mentioned. Do you recognize the product associated with this color? You know this product?

JAD: I—Pepto Bismol, yeah.

ROBERT: Yeah, but just say it right? Say it the way it should be said, Pepto, what did I say? Say it the way it should be said, Pepto-what did I say?

JAD: What? Bismol?

ROBERT: No, no, say only the first syllable. Pepto…

JAD: Bis…

ROBERT: Bis…

JAD: Are you implying that Bis, you're implying that Bismol stands for Bismuth?

ROBERT: I don't have to imply it, it's true. Pepto Bismol contains bismuth.

JAD: No. I don't know Robert, I mean I was with you right up until the point. But if I had to guess I would say that Bismol is just the name of the dude that made Pepto B, Jake F. Bismol.

ROBERT: [laughs] No. I'm telling you that in each bottle of—of pink liquid there are little black rocks, and that's just the truth.

JAD: I don't know man. I don't know.

ROBERT: Let me just prove it to you.

JAD: Prove it to me.

ROBERT: I will right now.

[Robert presses a play button]

JAD: What?

ROBERT: Hi.

JAD: Here Robert appears on the screen in chemistry goggles.

ROBERT: In a laboratory suit with a chemistry teacher by my side. Gale Carneaux from Brooklyn. And what you then see us do is we take 10 tablets of Pepto-B, we mush them up with a mortar and a pestle, we add some water, we add some hydrochloric acid, we shake, add some aluminum and you get to see little bits of black rock precipitate out of the Pepto Bismol.

JAD: Lots of them. I was surprised at how much black stuff is in there.

ROBERT: And then I showed the test tube to Jad.

ROBERT: Jad, look you can't deny scientific fact. That hiding inside every single Pepto Bismol tablet is pure, street level grade, crystal bismuth.

ROBERT: Inside Pepto B you will find an element that not only cures tummy aches…

JAD: Apparently it introduces death to the universe.

ROBERT: I think it's such a great element we should have a toast to Bismuth.

JAD: Yeah, let's have a toast.

ROBERT: Okay. Go bismuth.

JAD: Go bismuth.

JAD: And we closed the segment by both of us taking two big pint glasses, filling them up to the top with Pepto Bismol, and chugging it.

ROBERT: You always did it faster.

JAD: Just by a hair.

ROBERT: So special thanks to Gale Carneaux, my chemist, Sam Keene, who helped write this thing, Lauren Swarthout who got us the—got us the lab connection, and Zach Fannon who shot it, edited it, and re-edited it, and re-edited it.

JAD: [laughs] In typical Radiolab fashion.

ROBERT: So now we will pause.

JAD: Only to do some Bismuth.

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.