Jan 19, 2024

Transcript

LULU MILLER: Hey. Lulu here. There is this thing that radio producers love to say: radio is the most visual of all the storytelling forms. More than the movies, more than photography, more than TV, which maybe sounds counterintuitive, but the idea is that because your imagination is a bottomless resource, the visual experience that you get here is way more immersive and vivid and lush and has better special effects than any film studio could ever just financially, logistically produce.

LULU: Who knows if that's always true, but I will say the story that has stuck with me visually the most over decades of listening is the one I am about to play for you. It's called The Living Room, and it actually comes to us from another podcast that's been around for just about 20 years called Love+Radio. If you haven't heard of them, they make beautiful, sound-rich stories, sometimes a little dark, always special. And this episode, it is about bearing witness to something that maybe you weren't supposed to bear witness to. And the images from it, I literally have never been able to get them out of my head.

LULU: Before I play it, two quick notes: one, whereas we usually try to talk to everyone involved in a story, this episode is based on one person's vantage point. We did fact-check it to make sure the key elements did, in fact, take place but, you know, take it as one very powerful sliver of a complex situation.

LULU: And secondly, a warning: adult themes ahead. Probably not the best one to listen to with kids. All right, let us slip into The Living Room from Love+Radio.

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

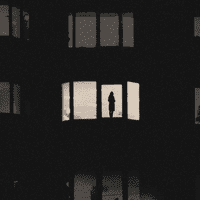

DIANE WEIPERT: So I'd been living in my apartment about 15 years, and one evening I walked in the living room, which has three bay windows which face the gardens in the back. And over half a block of gardens and across a small street, there was this bright window that I'd never noticed before, but it's at the exact eye level of my third floor apartment. And after a while I realized that I'd never seen it because there had always been curtains, and so it was always, I think, dimly lit, the curtains were often closed, and all of a sudden there's this bright light and no curtains, and it was like a movie screen. 15 years, and that window has meant nothing. [laughs] I haven't even noticed it, and now it's all I think about.

DIANE WEIPERT: There were new tenants, and it had always been a living room, and now it was suddenly a bedroom. And there were these two people in there, and they were naked, this young couple in their 20s. They were really lovey-dovey and they were always naked!

JAD ABUMRAD: That's Diane Weipert who tells the story. And she told it to radio reporter Briana Breen, who produced this piece with Nick and Brendan.

DIANE WEIPERT: The thing is they pushed their bed so that the head was up against the windows. So their heads, you could see both of their heads lying there. So you'd see things that you just—like, they were just shocking. I just had been there all of this time, and suddenly you could see people having sex really clearly, like, amazingly clearly. I had no idea that you could see so well across such a distance. And it was really uncomfortable. My husband and I were still adjusting to parenthood, and it wasn't the most romantic time in our—in our lives. And my son was probably three, and when you're new parents to a toddler, especially because he sleeps in the bed with us too, so he's, like, literally right between us, the last thing you need is a couple of hotties getting it on across the window, reminding your husband of everything he's not getting. [laughs]

DIANE WEIPERT: So to have this really beautiful, young woman, that was really thin and—and naked, all the time, really—you know, it was very frustrating. And she had this beautiful, tall, lanky, well-built boyfriend. And so at first, I just—because I felt like my husband was going to be staring at this naked woman all the time, I started closing the living room curtains, which is really kind of silly, and it made our room really dark. And we never closed those curtains, and so that didn't work.

DIANE WEIPERT: So I thought about, like, making a really big sign that said, like, "CLOSE YOUR CURTAINS" or "BUY CURTAINS." They didn't even have curtains. "BUY CURTAINS, WE CAN SEE YOU." And I thought about going by their building—I had no idea what their unit was—and leaving a note. And then I started thinking that was really silly and prudish, and started realizing that they were just young, and I had to just get over it and live with it and move on. And so that's what I did.

DIANE WEIPERT: We got really used to them, and they became sort of this symbol of what we used to be, you know, in our 20s. And they were living this really carefree time, and that's another thing that was kind of hard not to sometimes—when you're in early parenthood you get a little bitter, I think, about some of those freedoms. And we'd watch them sleeping 'til 11:00, while we've been up since five with our toddler. And we saw them eating breakfast on the roof together. So we got used to it. And we would notice, like, "Oh, look. They got a new plant in there." And they became sort of part of our lives, you know, because they were just always there, and never ever bought curtains.

BRIANA BREEN: Do you think all the neighbors in your building and the surrounding buildings also saw this?

DIANE WEIPERT: It's funny, I think that the way that we are positioned, because all of the buildings around us are different sizes, and our building is the tallest one on our block, but it's exactly at the right level to see their windows. I have a friend next door and then a friend across the way, and all of them have windows facing the gardens, but all of them are blocked. And I look at the other windows of the buildings around us, and I don't think anyone has this perfect level view.

DIANE WEIPERT: The irony is that I'm such a private person. And I don't know, am I supposed to have maybe respected their privacy and just looked away? But it's impossible, because that's the way the chairs face. They face the window. I couldn't not see them if I wanted to. But I guess I could have not gotten the binoculars.

DIANE WEIPERT: So time went by, and this is maybe a year and a half later, two years later, and I remember seeing their room and the light was on, but it was empty. And I thought that was strange, because it was five o'clock in the morning, and they never went anywhere early. And it was like that for, like, a whole week. It was just this empty room with a light on, and I thought that was strange. They didn't seem to be there as often, or maybe just she would be there, and he was gone for long periods of time. And we just kind of forgot about them. You know, we just—there wasn't as much action going on, and they weren't as present, and so we just kind of lived our lives and forgot about them for maybe seven or eight months.

DIANE WEIPERT: At the end of last year, in December, there was this night when my husband and I separately had both seen this woman, naked, sitting in the window. Kind of chubby, slump-shouldered woman who was just looking down at the street. And we both thought it was so strange, just couldn't figure out who she was and what she was doing and why she was naked. And a few nights later, there was this young man standing right at the window, by the bed. And he was skeletal, he was so thin, and he was bald, completely. And we realized it was the same couple. They had completely changed. He was sick. There was something serious wrong with him. After that, I just watched the window all the time.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Okay, we're gonna—we're gonna pause right here. Let's just—we'll be right back.

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. Let's get back to our story from Briana Breen and the folks at Love+Radio, Nick van der Kolk and Brendan Baker.

ROBERT: And so we're just gonna go back to the room, see—see what's—what we can see through the window.

JAD: Here's Diane Weipert.

DIANE WEIPERT: I just watched the window all the time, and he would sit—all day he was there. Because I work from home, and I would see him all day in the bedroom, either lying down or sitting at the computer. And then after a couple of weeks he was just lying down, and he was just there, and his bald head would be up against the pane of glass all the time. And she would be there, and she'd come in and she would bring him things, but mostly it was just him there by himself. And sometimes he would have his knees bent, and you could just see how skeletal they were; they were just bones. And sometimes he'd kick off the blankets, and he was just lying there naked and emaciated. And then after a while, he was just always burrowed under the blankets.

DIANE WEIPERT: I found myself thinking, like, "Well, maybe he's been through chemo and he's recovering, and he's going through this—this sick phase before he gets well." Because he's so young, you know, he's such a young guy.

DIANE WEIPERT: And so we had to go to Colorado to see my family for Christmas, and I worried all the time I was there. I thought about them, and I worried that he wasn't gonna be there when we got back. I worried all the time about it. When we got back, about 10 days later, he was still there, but his head looked so much smaller. And there were a lot of people there. And then I got out my binoculars, I got my birding binoculars. [laughs] I'm not proud of it, but at that point I felt so invested.

DIANE WEIPERT: It looked like people coming to say goodbye, and there was this sort of short, blonde, Midwestern-looking woman, who I guessed was his mother. And then there was this young guy who just kept pacing the halls. You know, you could just see—there were two doorways leading out of this room, and you could just see him go down one side and through the other, and then back and forth and back and forth. And I figured he was the brother. And it looked like the girlfriend's sister was also there. It was just a guest that looked like her.

DIANE WEIPERT: I remember there was just this little gathering going on in the living room right below. The neighbors were standing around and having drinks, and they had no idea at all what was going on right upstairs. I would watch people come and go, then after a while everyone left except for the girlfriend and the mother. And—and I spent—and I spent all that evening sitting vigil on the back of the couch and watching.

DIANE WEIPERT: And I remember the girlfriend lying beside him for a long time on her own, and she was just stroking his face so tenderly. It was so much affection that really transcends the kind of young love that you expect. All I could see was the top of his head all that time. And I remember later seeing her standing by the bed with the mother on the other side, and they were just all talking. And she put a hand on his forehead, she put the back of her hand on his forehead, and then she was wiping at her eyes. And you could tell that there was this—that there was this sense that something—that it was getting closer. Then I could see this reckoning, where she was wiping at her eyes and touching his forehead, and wiping at her eyes.

DIANE WEIPERT: And there were candles lit, and this young woman was on one side, and his mother was on the other side. And they just were lying there for a really long time, and they had their hands just resting on his chest. And so I watched it for a long time.

DIANE WEIPERT: The mother and the girlfriend were lying on either side of him, and you could tell it was his—this was the end. I thought, "Now all that's left is the girlfriend and the mother—and inexplicably, me. Me. Like, I'm one of the three people at the deathbed." And they lay there for a long time, and then they just got up and they went into the other room. And I realized that it must have been the moment.

DIANE WEIPERT: And all this time, you know, I always had this sense that they're—they're gonna break up, they're gonna move out. Nobody that age stays together very long. And I had no idea, it was this beautiful love story. So the next day—the next day I got up and I went to the window first thing, and they were folding up blankets and stacking them on the bed, and I figured that he had been taken away. And so I was in the kitchen, and my husband called because he had—he knew how obsessed I had gotten with this situation, and he said, "There's activity over there." And I came running, and I got my binoculars and I looked. And I realized that he was still there, he was still on the bed, his body was still there. And it was the coroner. So the coroner and his assistant came, and they had these white, plastic gloves on. And they pulled his body to the edge of the bed and onto this white sheet, and I just remember the lifelessness of it. It looked so shrunken. It almost looked like a shrunken rubber proxy of a body, so incredibly dead.

DIANE WEIPERT: They wrapped him in the sheet, and they zipped him into a vinyl bag, and they put him on this kind of gurney. They took the gurney out, and I just had this very strange impulse, and I ran and threw on my coat kind of over my pajamas and ran out to the street, and ran to the corner. And I got there just as they were hauling him out. They were carrying him out, and the girlfriend was there. She was talking to one of them in the doorway, and they loaded him into this van. And I realized that they didn't know me at all. Like, I had no place to be there. And they looked at me, I remember the coroner's assistant looking at me like I was sort of a rubbernecker in the street, you know? Looking at this grisly scene. And I realized that's what I was. I had no place to be there, and suddenly it all felt so perverse.

DIANE WEIPERT: And so I went home. And I felt very strange about the whole thing. And I tried to tell myself that well, I never wanted to be part of their lives. I was the one that wanted them to put up curtains. I wanted them to shut the intimate stuff out. I was uncomfortable with it. I was the one that wanted out. And I started remembering all of a sudden, when I moved to that apartment so many years ago, and I was in my mid-20s, that I had to share the apartment with a roommate because it was too expensive. And my bedroom was in the living room. And I remember how when I first moved in, I pushed the head of my bed up against the three bay windows, so that in the morning I could see the sky. And I remember that I had no clue. It never occurred to me that anyone could see me. I remember that I felt like whenever I looked out the window I never saw anyone, and I never closed my curtains either.

BRIANA BREEN: Did you ever find out either of their names?

DIANE WEIPERT: I never have found out their names. And I looked through the local obituaries obsessively for weeks, and there was never anyone that fit his description. There was never anyone young enough, or that looked like him. So no idea. I walked by their place several times, and there are only numbers on the mailboxes and the buzzers, and there are no names, so I can't look up anything. I don't know. Yeah, I have no idea who she is. I have no idea who he was, no idea what he was sick with.

DIANE WEIPERT: Just a couple of days after it happened, she was up on the roof with a friend doing yoga. And I've watched her lying around a lot. She went out of town, I think, for a bit. And she's still there. I have been watching her recovery, and instead of being this young woman, she looks totally different. She looks so changed. She just looks like this very experienced, world-weary person. She has a job now that gets her up very early, because I get up at 6:00 and she's already dressed and heads out at, like, 6:15.

DIANE WEIPERT: And the other night I saw her, and she was in her bedroom. And she was wearing this baggy t-shirt, and all the lights were on. And—and she was dancing. [laughs] Just dancing around her room. So yeah, I want her—I want to move on. This young woman, that I was so cranky and bitter about, you know, now she's—now I feel so protective and kind of maternal, you know?

BRIANA BREEN: If you ran into her, like, at the corner market or something, do you think you could ever say anything to her?

DIANE WEIPERT: Yeah, if I ran into her, I wouldn't say a thing. [laughs] What would I say? "I have been watching you through your window." How creepy would that be? [laughs] Yeah, no way. She doesn't know that—she doesn't know that there's this person that—I don't know, this complete stranger that's out there really rooting for her, you know?

JAD: Diane Weipert told her story to radio reporter Briana Breen, who produced this with the folks at Love+Radio, Nick van der Kolk and Brendan Baker.

ROBERT: And Nick does have a little postscript here, which I think you ought to hear.

NICK VAN DER KOLK: Just after this interview was recorded last spring, Diane's neighbor closed her curtains and hasn't opened them since.

JAD: Special thanks to Aaron Belkin, Karen Duffin, Alison Sorrell and Brian Poesner. And thanks, of course, to Nick and Brendan and Briana for letting us air that piece. Do yourself a favor: go to LoveAndRadio.org and subscribe to that podcast. There are stories I have heard on Love+Radio that I just will never forget, like, have seriously burrowed themselves so deeply in my brain that I actually have nightmares. You should listen to them all. LoveAndRadio.org. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Thanks for listening.

LULU: All right. Lulu from the present with one last thing. There is a very special Radiolab live event ping-ponging its way across the country right now. It's been to LA and Boston and New York and Chicago and beyond, and it is about to make its very last stop in Seattle. So if you live in the Seattle area and want to see a Radiolab episode unfold with all the wonder and play and immersive musical sound design before your eyes, come check it out! It's Thursday February 15 at Town Hall, Seattle. Our senior producer Simon Adler will be dressed on the stage in a snappy white suit leading you through live music and interviews and stories and images from space—and an even stranger place called the 1970s. Again, coming to Seattle on Thursday February 15 at Town Hall, Seattle. Find out more and get your tickets at KUOW.org/events. Bye!

[LISTENER: Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is edited by Soren Wheeler. Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are our co-hosts. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, Becca Bressler, Ekedi Fausther-Keeys, W. Harry Fortuna, David Gebel, Maria Paz Gutiérrez, Sindhu Gnanasambandan, Matt Kielty, Annie McEwen, Alex Neason, Sarah Qari, Alyssa Jeong Perry, Sarah Sandbach, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster. Our fact-checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger and Natalie Middleton.]

[LISTENER: Hi, I'm Erica in Yonkers. Leadership support for Radiolab's science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox, a Simons Foundation initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.