Oct 31, 2013

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab.

ROBERT: And today, I thought I'd introduce you to a particular guy on a particular day in Manchester, England. It's 1952, and Alan Turing, a math professor, discovers that a number of things have disappeared from his home. Looked kinda like a burglary. He was missing a shirt, a pair of shoes.

JANNA LEVIN: An old pair of pants, maybe a compass.

DAVID LEAVITT: It was stuff. It was just household stuff. Nothing of any value.

JANNA LEVIN: Nothing of any value.

ROBERT: That's Janna Levin and David Leavitt. Both of them have written books about Alan Turing.

DAVID LEAVITT: And so being very literal-minded, he thought, "Well, what do you do when you're robbed? You call the police."

JANNA LEVIN: So the police come to his house, the detectives. He has this conversation, and they say, "You know, he's kind of a curious chap." They let him talk, and they're like, "It's a real shame we're going to have to arrest him."

ROBERT: Who?

JANNA LEVIN: Turing.

ROBERT: Why would they have to—they're just coming to ...

JANNA LEVIN: Because he's effectively implicated himself in terms ...

ROBERT: Here's what happened. The police sat Turing down and said, "Who do you think made off with those things of yours?" And he says to them ...

DAVID LEAVITT: He suspected the thief was an acquaintance of his boyfriend.

ROBERT: His boyfriend.

DAVID LEAVITT: Yes. Yes.

ROBERT: You see, at the time, there was a law in England ...

DAVID LEAVITT: Which criminalized, quote-unquote, "Acts of gross indecency between adult men in public or private."

ROBERT: So he told the cops that he was having sex with a guy, is that why ...

JANNA LEVIN: He doesn't exactly say we're having sex. But he says enough that it's clear.

ROBERT: Oh.

JANNA LEVIN: He was never ashamed of being gay. This was just not something, again, that he understood what the fuss was about.

ROBERT: So what happened to him? Was he convicted?

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah. He's convicted and he's ...

ROBERT: What's his sentence?

JANNA LEVIN: Estrogen pills and implants. Estrogen implants.

ROBERT: Oh my God!

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah. Chemical castration.

ROBERT: And when I learned this, I wondered if those policemen had any idea that the guy they were arresting was, first of all, one of the great minds of the 20th century, a war hero who single-handedly, almost by himself, shortened World War II by at least two years. Alan Turing then became a myth, but he was also a man. And that's what we're gonna do in this hour on Radiolab. We're gonna measure men against their myths. And sometimes those men will more than measure up.

JAD: Sometimes you might feel they don't.

ROBERT: And sometimes—in one case, anyway—they completely disappear. So today on Radiolab ...

JAD: Of men and myths. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich. And to get back to the Alan Turing story, long before he was arrested, when he was just a schoolboy around 15 or 16 in England.

DAVID LEAVITT: He gets to Sherborne School, which is the public school, as they say in England.

JANNA LEVIN: I guess you would call it a boarding school, boarding school for boys, where ...

ROBERT: What did he look like?

JANNA LEVIN: He had dark hair, very dark hair. Sort of square face. He wasn't unattractive, he was just so goofy.

ROBERT: So did the other kids make fun of him at school, or did he ...?

JANNA LEVIN: Yeah. I mean, he's teased, taunted, bullied, but he's not completely unhappy. He falls in love.

DAVID LEAVITT: With another student named Christopher Morcom.

JANNA LEVIN: He was very charming, very socially smooth, handsome. And they have this bond over science. It's an unrequited love.

ROBERT: Did he express his love to this other kid, or ...?

JANNA LEVIN: He was always sort of there, standing next to Chris Morcom, every class, right behind him, right next to him. And I think at some point Chris commented that, you know, "Maybe it's a little too much attention." But I don't think he really made a formal declaration of his love. But he did maintain a relationship with Chris' mother, even after Chris died. Chris Morcom died while he was still in school of Bavarian tuberculosis.

ROBERT: Huh.

JANNA LEVIN: One day, it was just an announcement he was dead. So I think it came as a complete shock to Alan.

ROBERT: The only love he had left at that point was mathematics. So he goes off to King's College, Cambridge to study math.

DAVID LEAVITT: Yeah, exactly.

ROBERT: He was still kind of a loner.

DAVID LEAVITT: If you look at photographs of Turing, I think I'm always struck by the fact that he always looks like he's not actually there. He looks like—he's like a lot of mathematicians, he lives simultaneously in two different worlds—the world that the rest of us live in, and a world lived in a kind of extraordinary world of abstraction.

JANNA LEVIN: You know, lying in the fields in Cambridge, he would have these epiphanies, these realizations.

ROBERT: And one day, he's lying in Grantchester Meadows—that's near the campus—and he's thinking over a pretty tough problem: is there a quick, automatic way to prove or disprove a mathematical proposition, which was a big question in math at the time. The ins and outs of which aren't all that important to us, what's important is that it led to Alan Turing's idea for, of all things, a machine.

JAMES GLEICK: The machine doesn't exist. The machine is never built. It is never meant to be built.

ROBERT: This is James Gleick, a science writer who has studied Turing.

JAMES GLEICK: It's the world's most impractical machine.

ROBERT: But it's very simple.

JAMES GLEICK: These were the elements of the machine.

ROBERT: Number one ...

JAMES GLEICK: Piece of tape infinitely long, so therefore it's already never gonna exist, because we can't have infinitely long pieces of tape. And ...

ROBERT: Number two, something that reads or writes ones and zeros on the tape. And number three, a set of instructions.

JAMES GLEICK: So if you've got a zero, then you go to the left and you write a one. Or if you've got a one, go to the left and you write another one. And you've gotta remember where you've been, so you have a certain amount of memory, but that's it. And then he proved that the machine could do anything.

ROBERT: You could add, of course, and then you could subtract and multiply. You could also do a little calculus—actually a lot of calculus. You could do trig and mathematical proofs and sophisticated mathematical proofs.

JAMES GLEICK: Anything that could be done in mathematics mechanically could be done by his imaginary, idiot, simple machine.

ROBERT: Is this such a big idea? I mean, all you're saying really, is he figured out how to put logic, or actually how to program a machine.

JAMES GLEICK: [laughs] Okay. But no, Robert, you're already cheating because as soon as you say you're gonna give the machine some logic ...

ROBERT: Yeah?

JAMES GLEICK: ... and then as soon as you use the word "program," you're using very modern bits of knowledge that we've all internalized. But the idea of putting logic into a machine, no one thought of that. That's just weird!

DAVID LEAVITT: Machines at that time, bear in mind, were generally single function.

JANNA LEVIN: The idea that you do your email on your computer and Photoshop, you know, you don't buy a different machine. That is ingenious. That traces back to Turing's original idea, that I can build an electromechanical brain and I can teach it how to do different things.

ROBERT: This was the dawn of the computer age.

JANNA LEVIN: "Computer" used to mean a person.

DAVID LEAVITT: Usually a woman who would sit and do mathematics.

ROBERT: And now we got this guy who's saying that with a simple formula—tape, code and a set of instructions—we can give human-like abilities to a machine. And not just the abilities of our hands, but the nimble ability of our beautiful brains.

JAMES GLEICK: It's a beautiful, magical, simple idea. Turing's machine is Cézanne's watercolors, it's—it's Bach's Prelude. He was a lonely 22 year old just thinking, and he invented a thing that lives in the minds of every computer scientist today. He didn't realize that just a few years later he was gonna be applying these same skills to winning the war for—for England.

[NEWS CLIP: The Battle of London, which began with strong forces of Nazi bombers attacking the capital at night, led to a big fire on the waterside early in the ...]

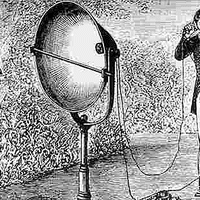

ROBERT: It's 1940, and the German high command is sending secret messages written in code to naval commanders, to U-Boat captains, saying, like, "Sink that ship, mine this harbor." The messages were encrypted in this crazy-fangled encrypting thing that they called the Enigma Machine.

JANNA LEVIN: Kind of a typewriter. So ...

ROBERT: They would type, "Bomb that boat"—in German, of course—and the machine would swap the letters and turn the type into gibberish.

JANNA LEVIN: But they changed the settings every transmission, and what this meant is that it was considered by both the Germans and the British to be uncrackable.

ROBERT: Except Winston Churchill thought, "Let me try." So in total secrecy, British Intelligence brought together the most talented amateur decoders that they could find.

DAVID LEAVITT: They chose mathematicians.

JANNA LEVIN: Chess champions.

DAVID LEAVITT: People who could solve the Sunday Times crossword puzzle extremely fast.

ROBERT: And they were all instructed to go to a set of buildings halfway between Oxford and Cambridge. It was a place called Bletchley Park.

DAVID LEAVITT: But the architect of the effort, really, was Alan Turing. He thought, "Well, this code is generated by a machine, therefore a machine can be built that will be able to break the code." So he built this machine that was called The Bomb. And it was ...

ROBERT: And it was huge. It was the size of a wall, and it could try out all kinds of different solutions to this breaking the code problem. And Turing decided to focus this machine on one little Achilles heel that he found in the code itself. At the beginning of a typical message, a German would get on the machine, and he'd have ...

JANNA LEVIN: Sort of habitual openings.

DAVID LEAVITT: You know, phrases that were very, very commonly used. And the Germans were fairly unimaginative.

ROBERT: Unimaginative at the start, like, you know, "Heil Hitler!" Or, "Good morning!"

DAVID LEAVITT: Yeah.

ROBERT: Or something like that.

DAVID LEAVITT: Exactly.

JANNA LEVIN: Heil Hitler, or the weather, or ...

ROBERT: So "Heil" would be H-E-I-L.

JANNA LEVIN: Right, yeah.

ROBERT: There's your in.

JANNA LEVIN: And then they realized that they could actually crack the code because of this, I would say, misstep.

[NEWS CLIP: Throughout the world, throngs of people hail the end of the war in Europe!]

ROBERT: When the English realized that Alan Turing and his team had broken the code, did that make Alan Turing into a superstar? I mean, did he get, like, a birthday greetings from the Queen?

DAVID LEAVITT: No, not at all. Because it was all top secret.

ROBERT: Well, does that mean that King George didn't know of Alan Turing, or Winston Churchill didn't know of ...

DAVID LEAVITT: Churchill certainly knew.

JANNA LEVIN: Churchill definitely took a particular interest in Turing and Turing's transmissions.

ROBERT: Oh, he did?

JANNA LEVIN: Sure.

ROBERT: Oh!

JANNA LEVIN: No, he's a war hero. There's no question about that. His contribution is of crucial importance in terms of turning the tide of the war in favor of the Allies.

ROBERT: And yet ...

JAMES GLEICK: As far as I'm aware, Turing was never thanked or acknowledged for what he did.

ROBERT: Well if I were King George, I would have, like, sent him a little, um ...

JAMES GLEICK: He didn't.

ROBERT: Having defeated the Enigma Machine, Turing now goes back to his first love: the Turing Machine. Mathematicians all over the world are now building computers and big, refrigerator-sized contraptions, actually. There was one at Manchester University, where Turing took a teaching job. And the one there did a lot more than just math.

JAMES GLEICK: And the machine could do all sorts of things. I believe it could sing.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAMES GLEICK: I'm pretty sure it could sing "God Save the King."

ROBERT: Really?

JAMES GLEICK: Not very well.

ROBERT: This is what it actually sounded like. It's not something you'd really want to march to.

JAMES GLEICK: It was not the machine that Turing ideally would have liked to build.

ROBERT: Turing had a bigger idea at this point.

JAMES GLEICK: The idea of the thinking machine. He really invented the field of artificial intelligence, and was the first person to hypothesize about whether a machine could actually be said to think.

ROBERT: And not just think, thought Turing, but maybe flirt with you a little bit, or joke with you. To have a sentience inside an electronic, manufactured mind.

JANNA LEVIN: And when people said, "How would you know that mind was truly sentient?" He said, "Just ask it."

ROBERT: Turing did come up with a test, a way to test whether a machine is doing something like thinking, like human thinking.

JAMES GLEICK: What we now call the Turing test.

ROBERT: We've described it on our show before.

JAD: How we'll know is ...

ROBERT: This from the show we called "Talking to Machines."

JAD: Get a person, sit them down at a computer, have them start a conversation in text.

BRIAN CHRISTIAN: You know, "Hi, how are you?" Enter. "Good" pops up on the screen.

JAD: Sort of like internet chat.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: So after that first conversation, have him do it again and then again. You know, "Hi. Hello. How are you?" Et cetera.

BRIAN CHRISTIAN: Back and forth.

JAD: But here's the catch ...

BRIAN CHRISTIAN: Half of these conversations will be with real people, half will be with these computer programs that are basically impersonating people.

JANNA LEVIN: If you can put this thing behind a curtain, and you talk to it and it convinces you that it's intelligent and alive and sentient, then it is. What's the big fuss?

ROBERT: But there was a big fuss.

JAMES GLEICK: One second.

ROBERT: A neuroscientist at the time, Sir Jeffrey Jefferson, turned to Turing and said, "How dare you! No machine will ever think like a human, because no machine can feel like we do in all the ways we do."

DAVID LEAVITT: "Pleasure at its success, grief when its valves fuse, be warmed by flattery, be made miserable by its mistakes, be charmed by sex, be angry or miserable when it cannot get what it wants."

ROBERT: Huh.

DAVID LEAVITT: And Turing's response to that was, "Well, I can say the same thing to you." You know, I can say to you, Robert, "I don't know what's going on inside your brain. You tell me what you're feeling and what you're experiencing, but how do I know that what you're—how do any of us know that any other human being is a human being?"

JANNA LEVIN: Turing is really one of the first to say—he's the first to say, "It's not just that I want to build a machine that can think, it's that we are machines that think."

DAVID LEAVITT: We are nothing more than flesh, blood, neurons. We are just machines ourselves.

JANNA LEVIN: Just soulless, biological machines. And this isn't a dark moment for him.

ROBERT: It's a moment of acceptance, says Janna. But this time, it's not about math or science, it's about something bigger. It's about the nature of the universe and our place in it. And according to David, not only did Turing feel like he himself was kind of a machine, he felt a kinship with all the thinking machines that would ever be manufactured in the future. All those mechanical minds. He felt he had something in common with them.

DAVID LEAVITT: For Turing, the machines were more likely to be victims—victims of prejudice, victims of injustice, victims of people like Jefferson. Jefferson is saying to the machines, "You don't think because I say you don't think." And, you know, England was saying to Turing, "You can't be what you are, and we're going to change you."

ROBERT: Which brings us back to where we started this show. It is now 1952. Alan Turing has been convicted of gross indecency, a crime punishable by, as we told you, a jail term or the court can order you to take hormone injections.

DAVID LEAVITT: And he was given a choice. He could go to prison or he could be, quote-unquote, "cured." And the cure consisted of massive doses of estrogen.

ROBERT: Nobody important went and said to the judge, "Here's a character reference."

DAVID LEAVITT: No.

ROBERT: "By the way, this guy won the World War that we just fought." Or ...

DAVID LEAVITT: Well, I suppose you could say that they were cutting him a break by not sending him to prison, by giving this horrific, horrific alternative.

ROBERT: What were the hormones supposed to do?

DAVID LEAVITT: It was the crudest kind of pseudoscience. There was some claptrap theory that homosexuality could be cured through injections of estrogen. What it really did was it made him ...

JANNA LEVIN: Impotent and profoundly depressed. He grows breasts. This certainly doesn't work to repress his homosexuality. He's still vocally gay.

ROBERT: But he's also worried that because he's now famously gay, his court case being in the papers and all, that everybody from now on will dismiss his ideas. Writing once to a friend, he said ...

DAVID LEAVITT: "I'm rather afraid that the following syllogism may be used by some in the future. Turing believes machines think. Turing lies with men. Therefore, machines do not think." It is signed, "Yours in distress, Alan."

ROBERT: The hormone treatments ended. He kept working, but his mood darkened.

DAVID LEAVITT: Turing's favorite film was Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. And he particularly loved the scene where the—the witch dips the apple in the brew and she chants, "Dip the apple in the brew, let the sleeping death seep through."

ROBERT: One night in 1954, it was June 8, he was at home, and at some point during that night ...

JANNA LEVIN: He kills himself.

ROBERT: How?

JANNA LEVIN: He laces an apple with cyanide and he bites from the poison apple.

ROBERT: He left no note. 55 years later, in 2009, the Prime Minister of Great Britain, Gordon Brown, issued a formal apology to Alan Turing. And in 2011, coming up on his hundredth birthday, more than 34,000 people signed a petition to the British government asking that Alan Turing be given a posthumous pardon for the so-called crime of "moral turpitude." In 2012, a government minister, Lord Tom McNally, said, "No, that we will not do." Here's the statement.

ROBERT: "A posthumous pardon was not considered appropriate, as Alan Turing was properly convicted of what was at the time a criminal offense. He would have known that his offense was against the law and that he would be prosecuted." And then, in 2013, the Queen herself issued a formal pardon, a power she rarely uses called The Royal Prerogative of Mercy. It was announced by the British Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, on Christmas Eve in 2013, who said that Mr. Turing's sentence would today be considered unjust and discriminatory.

ROBERT: It's an amazing life, and I'm in awe that anybody could have accomplished quite as much as he did—and suffered as much as he did. It's almost overwhelming. But when I think about it, there's a piece of what Alan Turing thought up that just hurts a little—at least me. This idea that machines can one day become, in fact, our equivalent.

JAMES GLEICK: This is still just such a powerful and emotional question for us to deal with. And I guess we're still divided between people who think that would be kind of a cool thing and people who think that would be a horrible thing. Partly because it makes us feel kind of bad about ourselves. There's nothing magical about us if we're just machines. But ...

ROBERT: Do you fall on—do you fall on one side of these lines?

JAMES GLEICK: No. I think—what I'm willing to say is I think we're just machines. And ...

ROBERT: Huh.

JAMES GLEICK: ... I think we're just made of matter. I'm sorry to be giving religious opinions here, because these are religious opinions, but for me, that doesn't make me feel that we're any less special. That makes—I think how—what a wonderful thing, that a collection of matter created by a process of evolution that lasted billions of years, how wonderful that this process and that these little collections of matter are able to produce Cézanne's watercolors and Bach's Preludes.

ROBERT: But ...

JAMES GLEICK: I can live with that.

ROBERT: ... could you—if I built you a computer that could create equally beautiful watercolors and equally beautiful musical compositions, would you feel happier, or diminished?

JAMES GLEICK: I think in a way, you're asking if you see how the trick is done, does it then vanish? Does it just become a trick? I feel the art I love is always art that I don't fully understand. There's some mystery there always. I don't quite fathom it. Now so when the machine produces music that is as lovely as the music that you and I love, I believe it will still be unfathomable.

ROBERT: James Gleick is the author of The Information. It's a book about information theory and artificial intelligence. David Leavitt has a book called The Man Who Knew Too Much. It's a biography of Alan Turing. And Janna Levin has a novel about Turing and Kurt Gödel, another mathematician, she calls her novel—and it's quite something, too, actually, it's kinda like a—well anyways, it's called A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines.

JAD: And we'll be right back.

[LISTENERS: Hey Radiolab, this is Billy Davenport. And Mila Davenport. We're listeners from Knoxville, Tennessee. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org. Thank you, Radiolab!]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert.

JAD: This is Radiolab. And today ...

ROBERT: Today we're doing a show called Of Men and Myths.

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: And we continue with a tale. It's actually about a person that we think we deeply admire, if by the way, you'd even paused long enough to admire him at all.

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: And the story comes from our own Pat Walters.

PAT WALTERS: This one gets kind of weird. I'm just gonna start just talking about myself.

ROBERT: Okay.

PAT: I think this is the closest I've ever come to dying.

JAD: Really?

PAT: It happened when I was 11, so I was in sixth grade. I was at lunch in the cafeteria. Lots of kids milling about, and I was sitting at the table with my best friend eating my little packed lunch that my mom had made for me. And I was eating an apple, and all of a sudden, I—I couldn't breathe.

JAD: You just—you started choking?

PAT: Yeah. And I put my hand up in the air, none of the cafeteria ladies came over. And I put both my hands in the air, and they finally came over and dragged me across the hall to the nurse's office. And ...

ROBERT: You're choking all the way to the nurse's ...

PAT: All the way to the nurse's office, yeah.

ROBERT: Gasping for air kinda choking?

PAT: No, just totally clogged up.

ROBERT: Clogged up.

PAT: And I get over there, and someone calls the paramedics.

JAD: Wait, how much time has passed since you—since you breathed?

PAT: Like two, two and half minutes, I think.

JAD: Really? That long?

PAT: Yeah.

JAD: Wow!

PAT: But then the nurse grabs me, wraps her arms around me, jerks me really hard under the rib cage and—pop!—this apple peel shoots right across the room.

JAD: Nice!

ROBERT: Like a projectile kinda—pow!—kinda thing?

PAT: Yeah, it was like in a cartoon. I mean, I don't actually remember, I have a terrible memory, but I've pieced this together from talking to my mom. And this story's just this thing that's been around. You know, I've told it a million times, it comes up at family gatherings. And I don't know, maybe a year ago, I was reading some things online about the Heimlich maneuver. I don't even know how I ended up there, and I realized I didn't know who actually is Heimlich? I didn't know anything about him. Like, who is this guy who invented this maneuver that saved my life?

[phone rings]

PAT: And that's when I discovered a story I totally did not expect.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Hello?

PAT: Hello, this is Patrick.

HENRY HEIMLICH: You downstairs?

PAT: I am.

JAD: Who's that?

PAT: That's Doctor Heimlich.

JAD: What?

HENRY HEIMLICH: I'll buzz you in. Take the elevator to four and turn left.

JAD: He's alive?

PAT: Yeah.

JAD: I just would have assumed he died, like, a hundred years ago.

PAT: Yeah, so he lives in Cincinnati. And I went to see him because ...

ROBERT: [laughs] You went to see—does that happen to you every time—like, if I told you ...

PAT: Well, this is what's cool about our job, right?

ROBERT: Yeah. "Oh, I've heard of him, I guess I'll go meet him."

PAT: I kinda wanted to say thanks!

HENRY HEIMLICH: Oh, I accept! [laughs]

PAT: Good to meet you.

PAT: And I wanted to find out, you know, the story of how he came up with this thing.

PAT: Can you just say who you are so I have it on tape?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Doctor Henry Heimlich of the Heimlich maneuver. [laughs]

PAT: Okay. And many other things that we'll talk about.

HENRY HEIMLICH: And each of them is saving many, many lives.

PAT: That's a matter of some debate. But let's just start the story at the beginning. And for our purposes, the story starts in the summer of 1941.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yes.

PAT: Heimlich was 21 years old, and he was on a train heading back to New York City from a summer camp that he worked at upstate. And as the train is going along the shore of this lake, the front end of it jumped the track.

HENRY HEIMLICH: The whole engine jumped into the middle of the lake. I jumped off and walked up to the front to see if anyone was hurt.

PAT: And as he approached the front of the train which was sort of sticking in the water, he saw this guy trapped.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Under the water with his feet under the train wheel.

PAT: Like, his feet were stuck and he was kind of hanging down into the water?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Correct.

PAT: The guy's head was bobbing up and down. He was desperately trying to keep it above the water.

HENRY HEIMLICH: So I jumped in the water and I held him up.

PAT: Kinda hooked his arms under the guy's armpits and lifted his head and shoulders.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Out of the water. And I held him for a long time.

PAT: For an hour or so.

HENRY HEIMLICH: And ...

PAT: And by the time the paramedics arrived and freed the man, a crowd had formed.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yeah.

PAT: And as Heimlich crawled out of the water ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: A couple near me said, "You saved a life. You saved a life."

PAT: That was the first time. After college, Heimlich went to medical school and became a ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Thoracic surgeon, a chest surgeon.

PAT: Started saving lives for a living. Then he joined the military.

HENRY HEIMLICH: I was in the Navy.

PAT: Navy surgeon.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Because I like ships and the sea.

PAT: Where he saved more lives.

HENRY HEIMLICH: [laughs]

PAT: And while he was overseas, he noticed that many times soldiers who got shot died not necessarily because they bled out, but because the bleeding from the wound would fill their chest and crush their lungs.

HENRY HEIMLICH: I'm thinking ...

PAT: There must be a way to solve this.

HENRY HEIMLICH: And one day ...

PAT: It hit him.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Why not a valve? So I ran to the five-and-ten-cent store.

PAT: Bought a few simple parts, and actually made this tube device that you could slip into a wound that ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Takes the air out and blood and lets nothing in.

PAT: It's called the Heimlich chest drain valve.

HENRY HEIMLICH: This is the tube and this is for the valve.

PAT: He showed me one of them. It's just a small six-inch tube with a little plastic flap that only lets air go one way. Really simple. But during Vietnam, the US Army bought 20,000 of these valves, distributed them to infantrymen.

HENRY HEIMLICH: When your buddy got shot in the chest, you slipped the tube into the chest and it saved his life.

PAT: And they're still around today. I called the company that makes them, and they told me that four million have sold since the 1970s, which translates to, like, who knows how many lives saved?

JAD: Wow, so this dude's amazing!

PAT: Wait, we haven't even gotten to the good part yet. One morning, in the winter of 1972.

PAT: Set the scene for me. So you were—at that time, you were living—you were living here?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yes, I was living here.

PAT: Heimlich is drinking his coffee, reading the paper. And he happens upon this one article about people who die in restaurants.

HENRY HEIMLICH: In those days, many people who died in restaurants, they were thought to be having heart attacks.

PAT: Mm-hmm.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Until an autopsy was done.

PAT: And the article quoted a coroner who'd done a bunch of these autopsies, and had found that actually no, these people had choked. The article went on to explain that more than 2,500 people ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Thousands of people were dying ...

PAT: Every year. From choking.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yes. I think it was the sixth-leading cause of accidental death.

PAT: Higher on the list than guns.

HENRY HEIMLICH: And the worst thing was that the great majority were children.

PAT: And nobody knew what to do about it. You could, like, thump a person on the back. But some doctors warned ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: That if you hit them on the back, the choking object would go deeper into the airway.

PAT: Do you—do you remember if there were people trying to come up with, like, devices? I feel like I read something about ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yes, there was one who had a, like ...

PAT: Like a pair of plastic pliers.

HENRY HEIMLICH: You would jam that in.

PAT: All the way through?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Apparently.

PAT: Another guy invented a sort of vacuum that you'd use to suck the food out. Not surprisingly, these things ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Just weren't effective.

PAT: People were getting desperate. I found this little clip from the New York Times, which described this guy whose wife choked on a piece of food in a restaurant. And not knowing what else to do, this guy, who happened to be a surgeon, grabbed a steak knife off the table and tried to perform an emergency tracheotomy.

ROBERT: On her neck? Like, on her ...

PAT: Yeah.

JAD: Oh!

ROBERT: And what happened?

PAT: She died in the restaurant.

JAD: Wow!

PAT: So Heimlich was reading about all of this, and being a thoracic surgeon ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: A chest surgeon.

PAT: ... he had an idea.

HENRY HEIMLICH: I realized that there was enough air in the lungs, if you could compress that air ...

PAT: Push it up against whatever was clogging the windpipe ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: ... you could carry the object out of the mouth.

PAT: So he gets a dog.

ROBERT: He got a dog?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yes.

PAT: Where'd you get it?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Oh, we had a laboratory that had some dogs there.

PAT: This wasn't like Fido, the Heimlich family pet.

HENRY HEIMLICH: No, no.

PAT: Laid the dog down on the operating table. And then he jams this piece of meat ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Probably beef.

PAT: ... down the dog's throat.

JAD: Did he at least sedate the dog before this?

PAT: Dog is anesthetized. And he ties a piece of string around the beef in case he needs to pull it out.

ROBERT: Okay, that's ...

JAD: Oh.

PAT: But anyway, the clock is ticking. He gets behind the dog.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Took my fist just above the belly button and pressed it there. Nothing.

PAT: So he tried again.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Repeated it. Nothing.

PAT: And then, on the third try—pop!—that beef ball ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Flew right across the room. I knew we had it.

PAT: So in 1974, Heimlich wrote up a little description of this maneuver and sent it to a medical journal. Pretty soon, that got picked up by a national paper.

HENRY HEIMLICH: The Chicago Daily News. And not quite a week later ...

PAT: A retiree named Isaac Peehaw, who had just read about the Heimlich maneuver in the paper ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Came out on his porch and his neighbor started screaming for help.

PAT: Guy runs over to his neighbor's house, finds his neighbor's wife ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Face down in the food. And ...

PAT: Just like he'd read in the newspaper ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: He did the method and—pop!—a big piece of meat flew out of her mouth and she fully recovered. And so he was recorded as the first one to use the procedure.

PAT: Pretty soon ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Stories from around the country ...

PAT: Began pouring into Heimlich's mailbox. Los Angeles, California, Fresno, California ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: And it got out very quickly.

PAT: One about a babysitter saving the kid she was looking after.

HENRY HEIMLICH: The whole country.

PAT: Bangor, Maine. Somewhere in Florida. Here's one about a custodian who saved an eighth grader choking on a ravioli.

HENRY HEIMLICH: You know, they just kept coming in.

PAT: There was stories about celebrities being saved by the Heimlich maneuver.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Different actors and actresses.

PAT: Cher, Goldie Hahn, Walter Matthau, Carrie Fisher. And Ronald Reagan!

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Johnny Carson: Okay, I'm in—this is the symbol that you're choking, right?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Henry Heimlich: Right.]

PAT: This is Heimlich teaching Johnny Carson how to do the maneuver.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Henry Heimlich: I'm gonna put my arms around your waist.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Johnny Carson: Oh, yes!]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Letterman: Come on over here, and I guess you're gonna demonstrate ...]

PAT: He taught Letterman, too.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, David Letterman: ... how to do it.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Geraldo Rivera: I just wanna read you, Doctor Heimlich, one letter that you got from a third grader in Kentucky.]

PAT: This is him on Geraldo.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Geraldo Rivera: "Roses are red, violets are blue, I might be dead if it wasn't for you." A third grader saved from choking on an apple. And if you think ...]

PAT: And for most of us, I think, that's where the story seemed to end, with Heimlich as sort of a national hero. But the story goes on and gets kind of murkier.

ROBERT: What do you mean?

PAT: Like, at the height of his fame, Heimlich starts going to medical conferences and claiming that the Heimlich maneuver can be used for more than just choking.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Henry Heimlich: Now we have a new use for the Heimlich maneuver, and that's its use to stop an asthma attack.]

JAD: Asthma?

ROBERT: How? Because ...

PAT: The way he explained is that when you have an asthma attack, your lungs get filled with a lot of excess mucus, and if you do the Heimlich maneuver, it will expel the mucus and stop the asthma attack.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Henry Heimlich: In addition, you can prevent an asthma attack by using the maneuver to keep the mucus out of the lungs. You use it maybe once every week or two.]

JAD: I live with someone who suffers from bad asthma. I'm supposed to give her the Heimlich maneuver once a week to help her with her asthma? That just seems weird.

PAT: Yeah.

JAD: Well, that's ...

ROBERT: Well, does that work?

PAT: No, there's no proof that that works.

ROBERT: Huh.

PAT: And at the time, asthma experts attacked him, saying the idea was dangerous. And it wasn't just asthma. On TV, Heimlich began to argue ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: That you can also save drowning victims with the Heimlich maneuver.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Henry Heimlich: Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is not effective when the lungs are flooded with water. The way to save a drowning victim is to do the Heimlich maneuver first. The lungs will clear after four Heimlich maneuvers. The Heimlich maneuver expels the water from the lungs.]

ROBERT: Does it work?

PAT: No.

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: There are a lot of misconceptions about when someone drowns, that their—their lungs will be full of water.

PAT: This is Jonathan Epstein.

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: I'm the executive director of Northeast Emergency Medical Services.

PAT: Also a member of the American Red Cross' scientific advisory board. And he says what actually happens in most drowning cases—I didn't know this at all, is that ...

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: The back of the throat will kinda spasm or close off.

PAT: And keep water from getting into the lungs.

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: And it is so important to quickly start that CPR process to replace the oxygen that was lost.

PAT: By giving the Heimlich maneuver, you're not only wasting time that you could be using to put oxygen back into the victim, but you also put them at risk of—like, of vomiting. You do the Heimlich maneuver, they might throw up and inhale their vomit, which could make things even worse.

JAD: But did people take him—take this idea seriously?

PAT: Yeah. Several major companies that train lifeguards started teaching their students to use the Heimlich maneuver before doing CPR. And for years, thousands of lifeguards were taught to do the Heimlich maneuver first. And as the years went on, Heimlich's ideas got increasingly radical. In the early 1980s, he announced that he might have found a cure for Lyme disease, cancer, and ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: I believe that I have a possible cure of AIDS.

JAD: AIDS?

ROBERT: AIDS?

PAT: How do people usually react when you say you have a cure to AIDS?

HENRY HEIMLICH: I don't say it to the wrong people.

PAT: Because the secret to his cure ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Malaria.

PAT: ... kills more than a million people every year.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Malaria therapy.

PAT: This isn't Heimlich's idea originally. He got it from a guy named ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Wagner-Jauregg of Austria.

PAT: Who in the early 20th century ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: 1918.

PAT: ... started treating victims of neuro-syphilis by giving them malaria.

HENRY HEIMLICH: And he cured it.

PAT: Because the fever was so severe that the fever from the malaria would kill the neuro-syphilis, but not the person?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Correct.

PAT: And based on this work, Juaregg, the guy who came up with this ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: In 1927, we won a Nobel Prize for it.

PAT: It wasn't long though before antibiotics came along, and malaria therapy disappeared. But in the early 1980s, Heimlich figured maybe this could work for seemingly intractable diseases like cancer and AIDS. First thing he tried it out on was ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: Lyme disease.

PAT: He raised some money.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Got some volunteers. Went the University of Mexico in Mexico City.

PAT: And he ran this small, unregulated clinical trial, in which he infected these volunteers with South American malaria. The CDC caught wind of what he was doing, denounced the treatment, called it unsafe, but that did not stop Heimlich. And through the 90s and into the early 2000s, he ran other unregulated trials on cancer and AIDS patients.

HENRY HEIMLICH: In South China.

PAT: And in Africa.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Ethiopia.

[NEWS CLIP: Doctor Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health says Doctor Heimlich's theory about malaria therapy has been thoroughly debunked by medical science.]

PAT: This is from a report on ABC News that quoted one of the world's leading AIDS researchers saying there's no scientific reason to believe malaria therapy would be effective against AIDS.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Anthony Fauci: And it does have the fundamental potential of actually killing you. That is a big risk to put a person through in an experiment in which there's no fundamental basis to even imagine that it would work.]

PAT: Uh, what happened with Peter?

PAT: And the criticism wasn't just coming from medical experts.

PHIL HEIMLICH: I have absolutely no idea. Absolutely no idea.

PAT: This is Heimlich's eldest son, Phil. And he explained to me that several years ago, his little brother, Peter, came out and began publicly condemning his dad's ideas. He launched a website and started sending emails to reporters, leading eventually to dozens of articles, most of which were critical of his father.

PHIL HEIMLICH: Why does a son do that? I have no idea.

PAT: When I called Peter, he told me that he didn't do it for any personal reasons, but because he felt his dad's ideas were dangerous, that they were putting people's lives at risk.

PAT: And you told me—repeat for me what you ...

PAT: Phil didn't want his father to have to deal with questions about Peter.

PHIL HEIMLICH: Basically because of the pain that this has caused my parents, because of their age ...

PAT: In fact, he wouldn't even give us access to his father unless we agreed to that.

PHIL HEIMLICH: I just—I just don't want my parents to go through that.

PAT: Phil also had another condition: that we not include Peter's voice. We thought he'd waived that condition in a subsequent interview, and therefore we did include Peter's voice in the original version of this story. But Phil didn't see it that way. Even though some ambiguity remains, we've decided to resolve the matter by respecting Phil's understanding of our agreement for accessing his dad and removing Peter's voice from the story. We should say though that even though we removed Peter's voice, this version of the story contains the same facts as the original. Anyway, the whole family drama aside, Heimlich was happy to address his other critics. And he said the way he sees it ...

HENRY HEIMLICH: "Creative ideas are often attacked because people oppose change or do not understand new concepts."

PAT: This is from an article Heimlich wrote about his career for the Encyclopedia Britannica.

HENRY HEIMLICH: "When a prominent discovery is revealed, particularly if it provides an obvious and simple answer to an important question, experts who have worked for years unsuccessfully on the same problem, they lash out at the creator and the idea because they're upset at themselves to not find the solution. Creativity requires courage."

PHIL HEIMLICH: People who have genius and great ideas often—often have to struggle to get their ideas out.

PAT: That's Phil again, and he disagrees with his brother Peter when it comes to their dad's work.

PHIL HEIMLICH: Yeah.

PAT: In fact, they don't even really talk anymore.

PHIL HEIMLICH: I trust my father's judgment. I trust the way his mind works, and I trust his ability to find simple solutions to very difficult problems.

PAT: And everybody seems to agree that his most famous solution, the Heimlich maneuver itself, is an incredibly effective one. But lately, some people have started to question whether it's the best one. At the end of my conversation with John Epstein ...

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: In the American Red Cross ...

PAT: ... the Red Cross guy that we talked to before, he told me that every five years, all the major lifesaving organizations worldwide get together and review their guidelines for all different kinds of rescues.

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: It is an exhaustive scientific research process.

PAT: They look over ...

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: Case reports and case studies.

PAT: ... controlled experiments on animals and cadavers. And Epstein told me that two reviews ago ...

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: In 2005.

PAT: ... the report yielded some new information about choking.

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: It was very clear that back slaps or back blows ...

PAT: Just thumping somebody on the back between their shoulder blades.

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: ... appeared to be equally effective ...

PAT: As the Heimlich maneuver.

ROBERT: Really?

PAT: And in fact, the Red Cross ...

ROBERT: Wow!

PAT: ... upon finding this out, went so far as to change their recommendation for what you should do when you find someone choking from "just do the Heimlich maneuver," to "first, hit someone on the back five times, then do the Heimlich maneuver."

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: Yes.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Nonsense. It's unbelievable.

PAT: And also, the Red Cross no longer calls it the "Heimlich maneuver."

ROBERT: Whoa!

JAD: What do they call it?

ROBERT: What do they call it?

JONATHAN EPSTEIN: Abdominal thrusts.

JAD: Abdominal thrusts?

HENRY HEIMLICH: This is wrong.

PAT: And as I sat there with Heimlich, I did start to wonder, like, how will we remember this guy? Will we remember this guy? I mean, does—do those bad things that he did later in his career in any way put his legacy as a lifesaver in jeopardy?

PAT: When I told people I was coming here, a lot of people reacted with wonderment that you're still here. People thought you'd been dead for a hundred years.

HENRY HEIMLICH: That makes me feel very good.

PAT: Makes you feel good?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yes.

PAT: Why?

HENRY HEIMLICH: My name is something that they just know. They just know it so well that it is self-established, that these handful of people who were trying to do harm really don't mean anything. I mean, to me right now, it's a great pleasure to know my name means saving lives. And when I'm gone, it's still going to be the Heimlich maneuver, and it's still going to be saving lives. I could just pull up my Google alert with the name "Heimlich" on it.

PAT: Yeah, could you?

PAT: Heimlich has a Google alert that he checks pretty much every day.

HENRY HEIMLICH: Here. "Sycamore boy saves life of friend choking on atomic fireball." "Custodian recognized for saving choking girl."

PAT: You find dozens, hundreds of these stories of people being saved by the Heimlich maneuver.

HENRY HEIMLICH: "Off-duty police officer saves neighbor's life."

PAT: You don't find a lot of stories about the controversies surrounding drowning and malaria therapy, or the Red Cross' new guidelines.

HENRY HEIMLICH: "Oregon football player performs Heimlich on man at Beef Bowl." [laughs]

PAT: This is just from one week?

HENRY HEIMLICH: Yeah.

PAT: And flipping through these stories, it does give you the sense that this guy and his maneuver have somehow become kind of immortal. Which on the one hand I kind of get.

CINDY ENNIS: Hello?

PAT: Hello, is this Mrs. Ennis?

CINDY ENNIS: Yes.

PAT: This is Pat Walters. I don't — I don't know if you remember me, but ...

PAT: Just before I finished making this story, I found Mrs. Ennis, the nurse who gave me the Heimlich maneuver when I was 11.

CINDY ENNIS: That was lunchtime wasn't it?

PAT: It was lunchtime.

CINDY ENNIS: Yeah. An apple?

PAT: It was an apple, yeah.

CINDY ENNIS: Yes.

PAT: And after she gave me the Heimlich maneuver, I sent her a thank-you note, and she sent me back this letter.

CINDY ENNIS: All right. Tell me when to start.

PAT: Whenever you're ready.

CINDY ENNIS: Okay. Right now. "Dear Patrick, when I accepted a job as the school nurse in the Wilson School District 33 years ago, I told myself that I would never allow anything to happen to children in my care. To my sorrow, I have watched Whitfield children I loved die of cystic fibrosis, AIDS, accidents and cancer. I think when you said, 'I can breathe,' was one of the happiest moments of my life. I treasure yours and your parents' letter and the privilege of being your school nurse. Sincerely, and with a big hug, Cindy Ennis, R.N."

PAT: I get a little—I get a little choked up just listening to you read that to me. I feel uh ...

CINDY ENNIS: I feel it very sincerely, Patrick. I truly do. It was from the heart.

PAT: I think what I take away from this is that, like, I'll always think of that thing I call the Heimlich maneuver as the Heimlich maneuver. And so will Mrs. Ennis. But when I think about my kids—I don't have any kids but, like, the kids I might have some day, when they learn this thing, it won't be called the Heimlich maneuver. And based on what I know now, I really don't think that I would tell them to call it that.

JAD: Even though it saved your life?

PAT: Yeah.

ROBERT: Thank you, Patrick.

JAD: Thanks Pat.

ROBERT: And we'll be right back.

[LISTENER: Hey, this is Holly calling from Melbourne, Australia. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org.]

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert.

JAD: This is Radiolab. And today ...

ROBERT: Today we're talking about some legends and the men behind those legends. And for this next story ...

JONNIE HUGHES: Hi, how you doing?

ROBERT: Ah!

ROBERT: We met a guy.

JONNIE HUGHES: I'm Jonnie Hughes. I'm a documentary maker from Britain. I'm also a science journalist.

ROBERT: He's an author. He recently wrote a book.

JONNIE HUGHES: Called On the Origin of Teepees. And it's about ...

JAD: Teepees? Why?

JONNIE HUGHES: Well, if I'm being honest, it was because it was a sort of pun on the Origin of Species. Nothing much rhymes with species, but ...

JAD: Oh!

ROBERT: [laughs]

ROBERT: You see, Jonnie wanted to write a book about the origins of ideas the same way that Darwin wrote his book about the origin of species.

JONNIE HUGHES: So I went chasing off after teepees.

ROBERT: Which brought him to the USA, and then he ended up driving across the country.

JONNIE HUGHES: Straight across, going west into—onto the Great Plains.

ROBERT: As he did, the farms gave way to prairie and then to wide open fields. And it was at that point that he noticed something a little different: there was a distinct change in headgear.

JONNIE HUGHES: Yeah, as soon as you get onto the short-grass prairie.

ROBERT: Right after Bismarck ...

JONNIE HUGHES: There's a very obvious transition from baseball caps to cowboy hats.

ROBERT: And that got him to wondering, like, how did the cowboy hat get to the West? And he decided to do some research.

JONNIE HUGHES: So the answer to the question who invented the cowboy hat, it's straightforward.

ROBERT: And it goes like this. 1865, the Gold Rush. Colorado. Everyone's coming in from all over the world to make their fortune panning for gold. They bring their hats.

JONNIE HUGHES: So there's a sort of mixture of hats from all different parts of the world. From the north, from the south, from the cities. Quite a ridiculous collection of hats, we might say.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JONNIE HUGHES: You've got silk top hats.

ROBERT: No!

JONNIE HUGHES: Seriously.

ROBERT: In Colo—in the Gold Rush?

JONNIE HUGHES: In the Gold Rush.

ROBERT: That would be your Abe Lincoln hat.

JONNIE HUGHES: Great in the East Coast cities, pretty useless on the top of Pike's Peak.

JAD: Why? Because it gets blown off by the wind.

JONNIE HUGHES: Blown off. It gets wet.

ROBERT: So you've got your Abe, but you also have ...

JONNIE HUGHES: Raccoon-skin hats, the sort of Davy Crockett things.

ROBERT: Great in the winter, but come the summer ...

JONNIE HUGHES: They got full of fleas.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JONNIE HUGHES: And they made you really hot as well.

JAD: That's not good.

JONNIE HUGHES: You also had straw hats from the plantations from the South.

ROBERT: Which are, I don't know, kinda flimsy.

JONNIE HUGHES: There would have been some sombreros.

ROBERT: Not bad, actually.

JONNIE HUGHES: Yeah. Keep the sun off your eyes, keep you cool. But they have enormous brims.

ROBERT: The problem is, when it rains ...

JONNIE HUGHES: The water just collects and stays on there.

ROBERT: There you are in Colorado with lots and lots of hats ...

JONNIE HUGHES: But none of them were perfect. All of them were slightly unfit.

ROBERT: Enter Mr. John B. Stetson.

JONNIE HUGHES: He was the son of a hatmaker in the East Coast, and he came over looking for his fortune. And the story goes ...

ROBERT: When he landed in Colorado, he looked around and he immediately saw an opportunity.

JONNIE HUGHES: Went back to the East Coast, gathered his thoughts.

ROBERT: And in a moment of unnatural and inspired inspiration, if you can be so inspired, he saw ...

JONNIE HUGHES: The fully-formed cowboy hat.

JAD: In his head.

JONNIE HUGHES: Yeah. So he had the model in his head.

JAD: And what was it?

JONNIE HUGHES: So his model was it needed to have a wide brim to keep the sun and rain off your head, but not as wide as a sombrero, because that was impractical. But also much wider than, say, a top hat, which was useless.

ROBERT: And it needed to be waterproof.

JONNIE HUGHES: Because he knew it was wet over in the West.

ROBERT: Needed to have a high dome on top to keep you cool up there.

JONNIE HUGHES: He knew what it ought to be.

ROBERT: So after little hammering and stretching and cutting, he had the perfect hat. And he called it ...

JAD: The boss of the plains!

JONNIE HUGHES: Which everyone in the West wanted to be. So picture the scene: Boss of the Plains arrives. It's gorgeous, you want one. You threw away your horrible raccoon thing and you went for one of those. It very quickly became a status symbol.

ROBERT: That is story number one.

JAD: Pretty straightforward.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: It was the guy.

ROBERT: It's a guy.

JONNIE HUGHES: It's J.B. Stetson. He came up with the idea. He was a genius, he got it sold.

JAD: Okay, what's the problem with that story? It seems fine.

ROBERT: Well, the problem with that, says Jonnie, and he realized it the moment he landed out west and started to look into this.

JAD: Uh huh.

ROBERT: Close your eyes and imagine, you know, your quintessential cowboy hat.

JAD: You're asking me to do this?

ROBERT: Yeah, please just do it.

JAD: Okay, got it in my head.

ROBERT: Is it a high-domed ...

JAD: Yep.

ROBERT: ... broad-brimmed ...

JAD: Very. It's got a dent in the top.

ROBERT: Well see ...

JONNIE HUGHES: The picture that we have in our heads is not what Stetson invented.

JAD: Really? Why? I mean, what did Stetson's look like?

JONNIE HUGHES: Probably the dullest cowboy hat you could possibly imagine.

JAD: [laughs]

JONNIE HUGHES: No rolling at the edge of the brim, no dents on the crown. Had a little ribbon around it.

JAD: A ribbon?

JONNIE HUGHES: Yeah.

JAD: That's not very bossy, that's dainty.

JONNIE HUGHES: [laughs]

ROBERT: So Jonnie did some more research, and he now comes up—this is coming up now—theory number two to explain who or what designed the hat. Again, 1865. It's Colorado Gold Rush time, people are coming in from all over. J.B. Stetson shows up, he makes the hat. But the hat was very expensive.

JONNIE HUGHES: You couldn't afford more than one. So from then on for the next 10 years ...

ROBERT: You would wear it, like, all the time.

JONNIE HUGHES: You'd be picking it up all the time with the crown, so you'd be pushing these dents into it every time you sorta yee-hawed.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JONNIE HUGHES: And you'd also be sleeping on your hat, so you'd be folding over the brim. So within a few years, the cowboy heroes, these guys are turning up at the railhead towns with these—what we might call in Britain, knackered Boss of the Plains hats

ROBERT: That looked like a completely different hat than the one they bought in the store.

JONNIE HUGHES: Yeah. They'd be battered.

ROBERT: And, you know, think about this. If you're a young cowboy, and you're looking for your first cowboy hat ...

JONNIE HUGHES: Do you want one that looks like the guy who runs the hardware shop?

ROBERT: Who's got the pretty dainty one.

JONNIE HUGHES: Or do you want the one with the dent in it like your dad the cowboy.

ROBERT: And so hatmakers picked up on this, and they began producing pre-dented, crumpled, knackered hats.

JONNIE HUGHES: Stetson responded as well. You can look through the kind of order books of Stetson, and you will see the designs change over time.

ROBERT: All of which is to say, if you want to tell the story this way, you can say, "Yeah, Stetson was there, Stetson played his part, but when it comes to a true cowboy hat, the one we think of when we think of a hat, Stetson really didn't invent it."

JONNIE HUGHES: The cowboys did.

[Yahoo!]

JONNIE HUGHES: The entire population of cowboys were instrumental in choosing the future evolution of the cowboy hat. It's almost like the market's deciding, which in this case is cowboys.

JAD: And can I just plant my flag and say that seems like a very sensible theory.

ROBERT: It does, but ...

JONNIE HUGHES: But ...

ROBERT: Something about this story number two was still nagging Jonnie.

JAD: Oh, there's more?

ROBERT: He's gonna go one more round. Do we want to come with him?

JAD: I will go.

ROBERT: Here we go.

JONNIE HUGHES: The third answer to the question who invented the cowboy hat is no one did.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: Well, someone did.

JONNIE HUGHES: What I mean is that there were no mindful decisions going on here. Not even a community of people mindfully chose where the cowboy hat was gonna go.

JAD: Mindfully?

JONNIE HUGHES: Yeah. So ...

JAD: What do you suppose he means by "mindfully?"

ROBERT: This is where we get a little bit of science. You know that if you were, say, a mouse, and you were living in an environment, happily, and then all of a sudden things turn cold, if you have short hair, you're gonna shiver and then maybe die.

JAD: Right.

ROBERT: But if another mouse happens to have longer hair ...

JONNIE HUGHES: You know, they're gonna do better. They're gonna do better in life, they're gonna have more baby mice.

ROBERT: So over time in this community, you're gonna get more and more and more mice with longer and longer hair.

JAD: Makes sense.

ROBERT: Now these mice, they don't choose the length of their hair, they just have the hair they got. It is the weather, it is the local environment, that's what really shapes these mice. And you could think of the hat in the same way.

JONNIE HUGHES: We're looking at the hat shape itself. The hat shape is changing over time without any forethought.

ROBERT: Thanks to that gold rush in the 1860s, you've got a whole bunch of very different hats showing up on the Great Plains. And all those hats show up on heads, and those heads and hats are gonna have horribly cold winters, searingly hot summers. They're gonna be in the wind, they're gonna be out of doors, because the main occupation is gonna be moving cattle across the plains.

JAD: Mm-hmm.

ROBERT: In this very competitive hat situation, the hat that's gonna survive is the hat that keeps you comfortable, keeps you cool, keeps you dry. In other words, the cowboy hat. Therefore, in this third version of our story, according to Jonnie ...

JONNIE HUGHES: The environment created the hat.

ROBERT: The wind created the hat. The rain, the sun, the snow, the weather created those hats.

JONNIE HUGHES: Absolutely right.

ROBERT: This hat was just bound to appear in that place in that time.

JONNIE HUGHES: It would have been invented by someone. The environment was right.

JAD: There's something kind of poetic about the idea that the hat that was called the Boss of the Plains, and if your third movie is correct, then it's really the plains who are the boss of the hat, or something else.

ROBERT: [laughs] Yeah, that's true.

JONNIE HUGHES: Jad, that's brilliant. I like that one.

JAD: See on the other hand, I'm not sure I like it, because, like, I'm just thinking about all the edits that we do as storytellers. Like, for the pieces in the show, like, the thing we're always trying to do is kind of get to moments. And we're trying to always atomize everything, get down to the particular person who made the particular decision that resulted in the particular change. Like, that's what we want as storytellers. So in some sense, your scenario three is like the death of story, in some sense. It's the anti-story.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JONNIE HUGHES: Feels less glamorous, doesn't it?

JAD: Well, yeah. It runs counter.

JONNIE HUGHES: But you know what? Do you know what? When Darwin came up with the theory—well, when he published his theory of evolution by natural selection, that felt like a death in a way. Because it felt like you were taking away the creator, this amazing being. You were diminishing life to a sort of mindless process. So a lot of people criticized him for the same thing. It's not as romantic, it's not as—well, it is as awesome. It's just not in the same way.

JAD: All right. Well, we should go. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Thanks for listening.

[JANNA LEVIN: Hi, this is Janna Levin.]

[DAVID LEAVITT: Hi, this is David Leavitt.]

[JAMES GLEICK: This is James Gleick. and ...]

[JANNA LEVIN: I'm calling to leave the credits.]

[JAMES GLEICK: Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad. Our staff includes ...]

[JANNA LEVIN: Ellen Horne, Soren Wheeler, Pat Walters ...]

[JAMES GLEICK: Tim Howard, Brenna Farrell, Molly Webster ...]

[JANNA LEVIN: Malissa O'Donnell, Jamie York, Dylan Keefe, Lynn Levy ...]

[DAVID LEAVITT: And Andy Mills. With help from Arianne Wack and Damiano Marchetti.]

[JANNA LEVIN: Special thanks to Sean Cole. Yay, I got through it just as someone walked through the door! Okay, let me know if I have to do it again. Bye!]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

-30-

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.