Oct 27, 2017

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey, I’m Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I’m Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. So, Robert, one of my favorite sounds, of all time, is the sound of hearing people think. You know, of a—hearing a mind, kind of, formulate a thought, it wasn’t there until…

ROBERT: It clicks in.

JAD: Yeah. That’s just a beautiful sound, especially when the mind you’re listening to is a person who has shaped you, has shaped the show.

ROBERT: Sure.

JAD: So, today, a little bit of a departure. A couple of months ago, I got connected to a guy named Bill Hayes. A mutual friend, sort of, put us in touch.

ROBERT: He wrote a really good book actually about anatomy. Really good. I gave it to my son.

JAD: Really?

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: He’s a writer and a photographer.

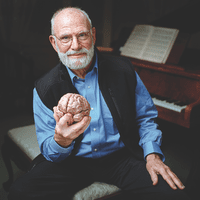

BILL HAYES: And I was the partner of the late Oliver Sacks and together we made tapes or recordings of conversations in the last year of his life.

JAD: Now, Oliver Sacks, one of the great, great writers of science.

ROBERT: Yeah. Masterful, masterful writer.

JAD: Yeah, we here at Radiolab have grown up with him—and his style of combining, sort of, clinical scientific observation with deep humanity and poetry, I feel like we’re always trying to walk in his footsteps in some way.

ROBERT: We do, we do.

JAD: And certainly we’ve had him on the show many, many, many times, so his voice will be familiar to a lot of you, but what you hear on these tapes—is an altogether different portrait.

JAD: And why—did you start these recordings?

BILL HAYES: Well, Oliver got his diagnosis of a terminal cancer in mid-January 2015.

JAD: He had—had cancer about nine years earlier, dealt with it. But it was back and spreading through his body.

BILL HAYES: The prognosis was six to eighteen months. And it was shattering.

JAD: Shortly after, Bill says they were sitting at the kitchen table talking.

BILL HAYES: Like I—I knew that he had things on his mind that he wanted to write and I said, “Well what are you—thinking about writing?” This was about four days after he got his diagnosis. And he paused and then he looked at me and said something like, “A month ago, I felt that I was in good health, even robust health. At 81, I still swim a mile a day, but my luck has run out.” And I said, “Stop right there” and I grabbed a pad and a pen and I said, “Start over.” And I began writing as fast as I could, as he dictated virtually the entire essay.

JAD: Wow. Just sort of spelled out like that?

BILL HAYES: Yeah, and—so we had the idea of getting a little audio recorder, a digital recorder so that it could be on hand at any time. Whether to record what he wanted to write or reminisce or to collect stories. After his death, I put the recorder in a drawer and didn’t pull it out again until over a year and a half after his death. I didn’t even listen to it—any of it to write my own memoir. I had been, kind of, very nervous about listening to them because I thought it would be very sad and it would just make me depressed and sad. But, I took it—I took the recorder out of the drawer where it had sat for 18 months and I pushed play and of course, it didn’t work because the batteries were dead. So, I had to scramble to find batteries and when I did and then pushed play…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Okay, this is a recorded conversation between OWS and Billy Hayes…]

BILL HAYES: I mean…

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: On February 6th.]

BILL HAYES: The hairs on my arms went up, it was as if he was alive.

JAD: This was the first recording you made with him?

BILL HAYES: Mmhmm. It was during dinner, we were eating at the time and he began telling me about his dreams.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Hmm dreams, I’ve been having a lot of, strangely arctic type of dreams, of a journey I have to make.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Yeah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Getting lost and getting found. Full of surprises. Maybe going through a door, which I would think would be a door into another room, but it is a door to a mountain landscape.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Uh huh.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: And—sometimes frightening ravines or having to edge along very narrow ledges, but then finally coming to some gracious, heavenly mountain meadow and then waiting. Dreams about journeys and approaching end and—it's a journey from where to where.]

BILL HAYES: This was February 6th, 2015. So, about three weeks after Oliver got his diagnosis of a terminal cancer and his immediate impulse was to write.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Again, this has been forced into my mind by the events in the past two weeks.]

BILL HAYES: Oliver was quite deaf, even louder than he realized he would whisper words to himself as he wrote them down on the pad. And he wrote with a fountain pen. For Oliver, writing was a form of thinking and the primary activity—for a human being.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: I knew my health—health, I knew my state of health and energy, at least some health managing, as a fit—and active 81 year old could hope to enjoy. And this, despite having known in the previous month, liver melanoma metastasis.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: You have new pages?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yeah, here. Things are out. This is from there.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Out? What I'm going to do is just leave that all there so you can look at it again.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks:Yes. No, no nothing must be destroyed. I am a creature of multiple drafts, as you know. Specific symptoms, perhaps it was of the general feeling—of disorder screws with them—and which may be tolerably severe—tolerably so severe. So severe. Patience—we long for death—for death. Now what happened to my other magnifying glass?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Eh, yeah, I haven’t…]

BILL HAYES: Oliver was the kind of guy who would take dictionaries to bed to read with a magnifying glass.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Can you bring my Chambers dictionary or look up a word for me?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Sure.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: You may need a magnifying glass and I have one here. Ah-ha. I also feel we're missing magnifying glass. There it is. Can you see if there's a word resipiscence? R-E-S-I…]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Yes. There is. Changed to a better frame of mind; to be wise.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: To be wise. Can you pull out the big dictionary and see if you can find any examples? In particular, I want to know whether, “a return to health”.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Okay.]

BILL HAYES: Here was a man with a huge vocabulary and love of writing, but still everyday he would be struck by a word that he wanted to look up. [ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Well, it immediately says repentance for misconduct.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: What did you say?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Repentance for misconduct. Recognition of errors committed, returned to a better mind or opinion.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: What's the origin of the word?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: To recover one’s senses, come to oneself again.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yeah, come to one’s senses. I think that’s not quite the word I want. Debilitating—tireless, disappeared—a little returned energy. Homeostasis is coming back—so cursed.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Here’s some ginseng.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Oh, thank you very much. To be myself—forceful thinking. The unexpected has happened, the hope for health—reawaken faith in some—tomorrow. Okay, Billy.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Yeah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Shall I read something to you?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Yeah.]

SPEAKER 1: “A general feeling of disorder. It is, especially when things are going wrong internally when homeostasis is not being maintained. When the autonomic balance starts listing heavily to one side or the other, that this core consciousness, the feeling of how one is, takes on an intrusive unpleasant quality. And now one will say, I feel ill, something is amiss. At such times when…”

SPEAKER 1: “Indeed everything comes and goes. And if one could take a scan or inner photograph of the body at such times, one would see vascular beds opening and closing. Peristalsis accelerating or stopping. Viscera squirming or tightening in spasms. Secretions suddenly increasing or decreasing. As if the nervous system itself we're in a state of indecision. Instability, fluctuation, and oscillation are of the essence and the unsettled state. This feeling of disorder, we lose the normal feeling of…”

SPEAKER 1: “The procedure, although relatively benign, would lead to the death of a huge mass of melanoma cells. These in dying would give off a variety of unpleasant and pain producing substances. Soon after waking from embolization, I was to be assailed by feelings of excruciating tiredness and paroxysms of sleep so abrupt, they could poleax me in the middle of a sentence or a mouthful. Delirium would seize me within seconds. Even in the middle of handwriting, I felt extremely weak and inert.”

SPEAKER 1: “On day 10, I turned a corner. I felt awful as usual in the morning, but a completely different person in the afternoon. This was delightful and wholly unexpected. I suddenly found myself full of physical and creative energy and euphoria, almost akin to hypomania. Exuberant thoughts rushed through my mind. How much of this was a re-establishment of balance in the body? How much an autonomic rebound after a profound autonomic depression? How much other physiological factors and how much the sheer joy of writing? I do not know, but my transformed state and feeling were I suspect very close to what Nietzsche experienced after a period of illness and expressed so lyrically in the Gay Science, “Gratitude pours forth continually as if the unexpected had just happened.” The gratitude of a convalescent for convalescence was unexpected. The rejoicing of strength that is returning of a reawakened faith in a tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. Of a sudden sense and anticipation of a future. Of impending adventures of seas that are open again.”

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Alright, where’s the microphone on this bloody thing? Where? Okay, you're recording this, right? The time is 9:20 in New York, it would be five hours difference with Greenwich Mean Time. And it is Monday 9th. And that's to say the 20th day after my embolization. And just 48 hours till the next one. End of recording. Pause.]

BILL HAYES: On March 11th, Oliver had the second embolization surgery, which would cut off blood supply to the tumors growing in his liver with the idea that it would give Oliver more time, more energy.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [pen scribing, flipping pages]]

BILL HAYES: We'd been together six years. I knew him well and yet—I'd never seen him with such focus.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Believe at times, I question…]

BILL HAYES: Just constantly writing.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yeah. I don't know what to call this piece. They can title it Ninth Avenue in the Glorious Forest. No…]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Well, I like The Future I Shall Never Know.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Sorry. Oh, that's excellent. Yeah, that's it. And I—think I need to put in, otherwise—just to indicate why it should…] [ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Have some Ensure.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: And I say to Billy, who is a good deal younger, who’s younger and who was a good deal younger than I am—originally I put Who Was Two Thirds My Age.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: [laugh]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Because I have to be precise.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: I like that.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Okay.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: It’s really precise.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Okay. Who’s Exactly Two Thirds My Age. Okay. So that's that. A little piece…]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: For the New Yorker?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Okay. Have some Ensure.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Thank you.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Sure.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: I like the idea of saying, “Billy, who is exactly two thirds of my age.” [laugh] It's not, it's not a fraction you’d expect to see. Three quarters? Yes. Half? Yes. But not two thirds. I like the idea of putting a tiny arithmetical conundrum.]

BILL HAYES: Ninth Avenue Reverie, published March 20th, 2015. “Driving down ninth avenue, choking on diesel fumes from a truck just ahead of us. I say to my friend, Billy, he's exactly two thirds my age, “I wonder whether you will see the end of internal-combustion engines, the end of oil, a cleaner world.” The thought zooms me away from ninth avenue to a forest world. In particular to the one described in That Glorious Forest, Sir Ghillean Prance’s book about his 39 visits to the Amazon in the past 50 years. He sees what we are doing to the Amazon and its many peoples. He speaks for conservation, sanity, reason before we destroy it all.”

BILL HAYES: “I went to that glorious forest in 1996—11 days of botany, study, and hiking, seeing hundreds of different species of trees in a single acre. I had planned, before I became ill, to go to Madagascar, to see its forests—and its unique fauna and other wildlife, especially the lemurs. I love lemurs. One has to see them, study them, to grasp the origin of our primate nature. But most of the forests on Madagascar have already been obliterated, and, not unnaturally, the lemurs are dying.”

BILL HAYES: “Honking horns bring me back to Ninth Avenue. I seem to have spent hours lost in reverie, thinking about the Amazonian and Madagascan forests, lemurs, “The Time Machine,” but we have scarcely moved, are still behind the stinking, lung-destroying truck. “Not in my life,” Billy answers.”

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: I—yes. Yeah, yeah, yeah, I’ve been reading a lot out loud to Billy.]

BILL HAYES: This is recording where Oliver is talking on the phone to Lawrence Weschler or Ren Weschler.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: But anyhow, he—I was due to have a—a CAT scan follow up on Thursday. I was terrified of this. In fact, what it did show was that 80% of the metastasis in the liver had been destroyed by the embolization. With luck, I should have two or three good months after this. Well, I—I just hope that I can see friends and write and maybe travel a little. Yeah, and I think next month, if I'm up to it, I’m gonna go to London to say hello and possibly farewell to—friends and family. And—I can't think ahead beyond.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: [Bells ringing.] Six, seven, it’s still one short. I’ll—so—semantics. Semantics—at ease. [pen scribbling] Use of elementary units—intimate relation.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Oh, I want to hear. I want to hear.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: “Over the years, I filled upwards of a thousand notebooks. Their contents are various, but three of them have had a special function, to record abnormalities of perception during times of sensory impairments or deprivation. The column notebook is a very modest affair. It is quite small and slips easily into a pocket. Crucial because I need to have it with me at all times. In increasing deafness, I am more and more prone to mishear what people say, but mishearings deceive one entirely. You accept what you hear. You accept what you see. If you’re mishearing, it is a novel, surprising concoction. One never gets used to them. The hundredth is as fresh, as absurd, and as thoughtful as the first.” Mishearing became—mishearing. “Take the car for a spin” became “Take the car for a swim”. I've noted that. Your hummus can you frame us. Therapist, invertebrate. Tarot cards, terra pods. Big time publisher is heard as a big time cuttlefish. I said “Did you say a poetry bag?” And you said, “No, I said a grocery bag.”]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: [laugh] I love the idea of a poetry bag.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes. I'm inclined, almost, to put them all in.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: I think they should all be in.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: I am a sheer mess. We'll—make the point. That sound trumps everything.]

SPEAKER 1: “One’s surroundings, one's wishes and expectations, conscious and unconscious, can certainly be co-determinants in mishearing. But the real mischief lies at lower levels, in those parts of the brain involved in phonological analysis and decoding, doing what they can with distorted or deficient signals from our ears. These parts of the brain manage to construct real words or phrases, even if they are absurd. And yet there's often a sort of style or wit, a dash in these instantaneous inventions. They reflect to some extent one's own interests and experiences. And I rather enjoy them only in the realm of mishearing. At least my mishearings. Can a biography of cancer become a biography of Cantor. One of my favorite mathematicians. Tarot cards can turn into terra pods. A grocery bag into a poetry bag. All or noneness into oral numbness.

And a mere mention of Christmas Eve, a command to kiss my feet.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Oops. No wonder I couldn't write anymore. I—must get more cartridges. I'm going through these too quickly.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: I want to reassure you. All of these thoughts are already in the draft.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Oh, very good.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Okay? So, I think it's time to let your weary mind rest.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes, okay. We’ll see each other in the morning.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Okay.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: If you could just kiss me whenever I had a dry mouth, I—be in heaven.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: [laugh] Do you want some more water?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes, I better raise my head a little.]

[DAVID: Hello, this is David from Berlin. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www. sloan.org.]

[JAD: Hey, this is Jad. Radiolab is brought to you by the John Templeton foundation, harnessing the power of the sciences to explore the deepest and most perplexing questions facing humankind. Learn about the latest discoveries in the study of hope and optimism, intellectual humility, and free will at templeton.org.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Um, um—would you like to pour out some wine for you and your elderly lover?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Sure. [laugh] You want some of this?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Okay. [laugh] You look very happy. Which one of these jackets appeals to you? If you're going to pick one, let's go to the start.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yeah, well, of course, I have to take my own unfortunate shape.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: No, no, no. I know. I want you to respond to them. Which one?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Oh, I see. I think I’m fond of this sort of routine jacket where its pockets sort flaps. Functional though it is, I don't know where I got that jacket.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: It’s so hot, Oliver.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Sorry?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: It's so hot.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Hot?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Hot. Do you know that word? Sexy.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes. Oh yes. Right.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: You're very handsome.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: You haven't had anything to eat.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Uh uh.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: You should have something to eat.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: I might go out. I sort of enjoy that on Sunday night.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes, I know.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: I get a little stoned and I go out into the neighborhood. Do you mind?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: No. I don't know that I'm good for much company, anyhow at the moment. Yeah, go rejoice. [clock ringing] I wasn't counting, how many did you hear?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: I didn’t count either.]

BILL HAYES: Oliver had enjoyed a couple of really good months of feeling well and fit and getting lots of writing done. He had completed not only A General Feeling of Disorder, a short piece Mishearings, his autobiography On the Move was published, he worked on a piece on the evolution of the eye and he'd completed a major case history on the performer, Spalding Gray. We made this wonderful trip to London for 10 days. After we returned from the trip, he knew that he would have to get another CAT scan to see how things were going. And I—would say that we kind of had a feeling, an optimistic feeling. He seemed to be doing well. So, he went into that hoping for the best, but it was exactly the opposite. The cancer had spread beyond the liver to other organs—that it—was looking very bad, indeed. Oliver, more than anyone I think, knew that time was running out.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: [pen scribbling] Billy? I wonder if I could ask you to look up something on the little box?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Sure.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: The 10 commandments. Yeah, in particular, the one about—the seventh day holy, I’m not sure what the exact—exact wording is...]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.]

That’s right, let me write that down. Exactly what I want. Gefilte fish—]

BILL HAYES: He was having a lot of discomfort and had to have a catheter implanted in his abdomen to drain off fluid that was accumulating from the tumors, which was around August 4th or 5th. It was really the only solution. And it was quite uncomfortable and it had to be drained, daily. And it also unfortunately ended his swimming. He was a great swimmer and he loved to swim, but he didn't complain. Swimming had come to an end. So, he put his head down basically and began working on this essay, Sabbath.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: At a time when you may…]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [piano playing] [pen scribbling]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: What are you doing?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Filling my pen.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [piano playing]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: What did you think I was doing?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: [laugh] I knew what you were doing, I just wanted to talk to you.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Good morning.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kate: Good morning. Did I miss the dramatic reading?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: It just started a little while ago. ]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kate: How are you?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Weak.]

BILL HAYES: His long time assistant editor, Kate.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kate: What are you writing about? Sabbath?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yeah, it’s going to be quite a long piece. Here, I’ve filled up my entire pad. “My mother went into”–get a chair. I don't want you looming.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: [laugh]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kate: I just–I like standing. Is this better?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Okay, fine, stand then.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kate: Back… Should I loom over here?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Okay. Yeah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kate: Okay.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: My mother and her 17 brothers and sisters had an Orthodox upbringing — all photographs of their father show him wearing a yarmulke, and I was told that he woke up if it fell off during the night.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: [laugh] Isn’t that funny?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Kate: I love that.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: “My father, too, came from an Orthodox background. But they were very conscious of the Sixth Commandment, “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy” and Shabbos, as we called it in our Litvak way, was entirely different from the rest of the week. When Shabbos came in, my mother would light candles, cupping their flames with her hands, and murmuring a prayer. And I gradually became more distant or indifferent”–I think it’s more indifferent–“to Jewish life, the synagogue–the Sabbath and the synagogue, in particular. Though there was no particular point of rupture or alienation until I was 18, which was then that my father, inquiring into my sexual feelings, compelled me to admit that I liked boys. “I haven’t done anything,” I said, “it’s just a feeling — but don’t tell Ma, she won’t be able to take it.” He did tell her, and the next morning she came down with a look of horror on her face, and shrieked: “You are an abomination. I wish you had never been born.” The matter was never mentioned again and a cordiality, even love was rebuilt. But her rueful, hateful words, her curse, made me hate Judaism, all religions in their capacity for inhuman bigotry and cruelty and it turned me, in part, to a self-hating, self-accuism, closet homosexual. I had felt a little fearful visiting my Orthodox family with my lover, Billy.”]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: [laugh]]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: “My mother’s words still echoed in my mind—but Billy, too, was warmly received and there was no hint of the terrible bigotry of 60 years old. This was made clear by Robert John when he invited Billy and me to share a Friday evening with him and his family. The peace of the Sabbath, of a stopped world, a time outside time, was palpable, infused everything, and Billy, I think was as conscience of this as I was. That I had been able, for the first time in my life, to make a full and frank declaration of my sexuality. That I was finally out of the closet, facing the world openly, with no more guilty secrets locked up inside me. And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, and my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural, that has never made sense to me, but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life—achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one’s life when one can feel that one’s work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest.”]

BILL HAYES: On August 14th, Sabbath was published in the New York Times. That same day, he began to dictate the table of contents for The River of Consciousness, the collection of essays, which he knew would be published posthumously. It was getting his house in order.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Um, I don't know that I am capable of much writing nor that I want to do any writing, but I hope I can, as I think out loud to you and to Kate and the quarter, home hospice… I think that I will require an amount of care, including intravenous, nursing, things beyond what you and Kate can provide. Or should. And this in turn should release you, you know, to be with my friends and comfort us. One last go at tempting my appetite, can you bring me a little bit of kedgeree.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: Just to mention, there is also chicken soup.] [ARCHIVE CLIP, Oliver Sacks: Yes, I probably should have some liquid.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Bill Hayes: I’ll just get you a little of each.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: [pen scribbling]]

JAD: Two weeks later on August 30th, 2015, Oliver Sacks died at home. In the last seven months of his life, he wrote and published nine pieces and there were many, many more that he started but wasn't able to finish.

ROBERT: And some of the essays he wrote are now in a new collection, published after he died called The River of Consciousness and that's just out.

JAD: The readers that you heard in the story were Radiolabers, Annie McEwen, Simon Adler, and Bethel Habte. Thanks also to Mike Paskash for engineering help. And this piece was produced by Karla Murthy.

EMILY: This is Emily calling from Houston. Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad and is produced by Soren Wheeler. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Maria Matasar-Padilla is our managing director. Our staff includes Simon Adler, Rachael Cusick, David Gebel, Bethel Habte, Tracie Hunte, Matt Kielty, Robert Krulwich, Annie McEwen, Latif Nasser, Malissa O'Donnell, Arianne Wack and Molly Webster. With help from Amanda Aronchick, Shima Ali-Ali, David Fox, Niger Fatali, Phoebe Wang and Katie Ferguson. Our fact checker is Michelle Harris.

[JAD: Hey, this is Jad. Radiolab is brought to you by the John Templeton foundation, harnessing the power of the sciences to explore the deepest and most perplexing questions facing humankind. Learn about the latest discoveries in the study of hope and optimism, intellectual humility, and free will at templeton.org.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.