Sep 23, 2016

Transcript

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

MOLLY WEBSTER: We're gonna start with a conversation that I had with Jad a few weeks ago.

JAD ABUMRAD: Okay.

MOLLY: So I like medical stories.

JAD: Mm-hmm. This I know about you.

MOLLY: This you know. And I read this website called StatNews.com, which does sort of really—it's like a new website out of Boston.

JAD: It's new, right?

MOLLY: I mean, basically it's this collection of really amazing, like, medical reporters, and I will click on stories that look interesting. And there was one about we've just grown embryos—human embryos for a long time in a lab.

JAD: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: And that was when I read the phrase "The 14-day rule" for the first time, and it was that apparently there's this thing that you can't grow an embryo in a lab past 14 days.

JAD: Huh.

MOLLY: Which I didn't even know you could grow an embryo in lab at all.

JAD: Right, right.

MOLLY: Or—or that people were. Or that—I mean, I guess I knew IVF happened.

JAD: Sure.

MOLLY: Like test tube babies.

JAD: How long if—in the average IVF situation, how long is an embryo in a dish for?

MOLLY: And then I realized I didn't actually even know that, either. So then I just spun out. So like, the whole article was just interesting to me because I was like ...

MOLLY: I don't know about any of this.

JAD: Right, right.

MOLLY: I'm Molly Webster.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Oh, and I'm Robert Krulwich. This is Radiolab.

MOLLY: And today on Radiolab. We're gonna zip down a wormhole into another universe, and Robert you're coming with me.

ROBERT: Okay. What—tell me about this universe before I buy a ticket.

MOLLY: The universe—oh, okay. You're going to want to buy a ticket, because in this universe are twins and souls and mice and something called the primitive streak. And they're all gathered together around a certain rule.

ROBERT: And remind me again what the rule was?

MOLLY: Well, so you know how you can fertilize an egg? You get an egg and a sperm and you put them together.

ROBERT: Yes.

MOLLY: Fertilizes the egg?

ROBERT: Right.

MOLLY: And then the egg—the fertilized egg, it multiplies, multiplies, cell divides.

ROBERT: Right.

MOLLY: So a scientist could take it to watch it grow to learn about human development. But then they have to stop at day 14. That's the rule.

ROBERT: Is this a medical kind of thing? Or a science limitation?

MOLLY: It is—it's medical—it's all those things. It's medical and it's science and there's, like, philosophy and ethics, and obviously religion. And ...

ROBERT: And that's the ticket I'm buying, huh?

MOLLY: Yeah, you're buying it now, right?

ROBERT: I see. The whole shebang.

LEROY WALTERS: I have water.

MOLLY: Okay.

LEROY WALTERS: I'll take a sip.

MOLLY: Okay.

MOLLY: And we're gonna begin with this guy, LeRoy Walters.

LEROY WALTERS: Okay.

MOLLY: He was an ethicist at Georgetown University, now retired. And to me, he is sort of the father of the 14-day rule.

LEROY WALTERS: I never—I never thought of myself as the father of the 14-day rule.

MOLLY: But he is. He totally is.

LEROY WALTERS: Well, we shouldn't forget the context of '73.

MOLLY: All right. So 1973, Leroy has recently graduated with a doctorate in ethics from Yale University and he's settling into his job. And at the time, medicine and ethics were on a sort of collision course.

LEROY WALTERS: Yes, yes. Mm-hmm.

[NEWS CLIP: Good evening.]

MOLLY: January, 1973.

[NEWS CLIP: In a landmark ruling, the Supreme Court today legalized abortion.]

MOLLY: Roe v. Wade happens.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, politician: It is clear, at least under present law, that an unborn fetus is not a person within the meaning of the Constitution.]

MOLLY: But just six months after that decision ...

[NEWS CLIP: The issue of fetuses and research done with them ...]

LEROY WALTERS: Fetal research became a hot topic.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, politician: Some of the testimony in here is shocking.]

MOLLY: There were news reports ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, politician: Of butchering and cutting up ...]

MOLLY: About dissecting fetuses, even an instance of decapitating fetuses.

JAD: Oh, man.

MOLLY: And then around the same time ...

[NEWS CLIP: ... used as human guinea pigs.]

LEROY WALTERS: Research involving human beings.

[NEWS CLIP: The controversial Tuskegee syphilis study ...]

MOLLY: News reports of the syphilis studies that were done on African-American men without their knowledge.

LEROY WALTERS: There was the sterilization of ...

[NEWS CLIP: Two daughters had been sterilized without their informed consent ...]

LEROY WALTERS: ... women with intellectual disabilities.

[NEWS CLIP: ... experiments in genetic research.]

MOLLY: Genetic engineering was coming into its own. You have all these questions swirling about, like, how we feel about the human body, whether or not we want to experiment on it? What do we protect, and what don't we protect? It's just sort of this whirlwind, and ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: You are about to see a historic birth ...]

MOLLY: ... then most relevant for our story ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: We are going to deliver her by Cesarean section.]

MOLLY: On July 25, 1978 ...

LEROY WALTERS: Scientists in the UK ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, doctor: We are now incising the uterus itself.]

LEROY WALTERS: Produced a child with the aid of in vitro fertilization.

MOLLY: The first baby that was born from an embryo that was grown inside a tube.

LEROY WALTERS: Baby Louise Brown.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, doctor: Baby's not opened her eyes yet.]

LEROY WALTERS: Everyone in the world was fascinated, but there were people who predicted doom.

MOLLY: What was the doom?

LEROY WALTERS: That in vitro fertilization would lead to reproduction as a form of manufacture.

MOLLY: So the government was grappling with, we need more regulations or we need as a country to think about, like, what the ethical guidelines are.

LEROY WALTERS: Right. So ...

[NEWS CLIP: The Department of Health, Education and Welfare ...]

MOLLY: And they put together something called the Ethics Advisory Board.

[NEWS CLIP: The panel of doctors, laymen, academics ...]

MOLLY: Even a Jesuit priest.

[NEWS CLIP: To consider ...]

[NEWS CLIP: ... some fundamental moral and ethical questions ...]

[NEWS CLIP: ... questions involved in test tube human fertilization.]

[NEWS CLIP: Its meetings and discussions open today.]

MOLLY: Now, as part of those meetings, the board will call on these expert witnesses. And one of those witnesses was our Boy LeRoy.

LEROY WALTERS: Right. The staff director ...

MOLLY: And they asked LeRoy, like, ethically tell us what we should be thinking about when it comes to embryos?

LEROY WALTERS: And how we are to regard them.

MOLLY: And he says, "Well, there's a spectrum. And on the one side, you could argue ...

LEROY WALTERS: ... that human embryos should be protected from the time of fertilization forward.

MOLLY: We shouldn't even be growing embryos in a lab at all.

LEROY WALTERS: But ...

MOLLY: Then there's the other side.

LEROY WALTERS: ... the most permissive position was that research could be done until about eight weeks ...

MOLLY: Because ...

LEROY WALTERS: A fetus at about eight weeks can have a reflex response to a stimulus.

JAD: Hmm.

LEROY WALTERS: And then ...

MOLLY: At some point a committee member turns to LeRoy and she says, where would you draw the line? He pauses and he says, "Well ..."

LEROY WALTERS: I would say for me, 14 days.

ROBERT: Why 14?

MOLLY: Well, LeRoy had a couple different arguments. For one, before 14 days ...

LEROY WALTERS: About 50 percent of early human embryos are simply sluffed off.

MOLLY: They're just sort of shed from the woman's uterus.

LEROY WALTERS: And don't develop further.

MOLLY: So the thinking was, if we're already losing 50 percent of them naturally ...

LEROY WALTERS: We don't have strong moral obligations toward early human embryos.

JAD: I see.

LEROY WALTERS: You can even pose it as a metaphysical question. If these are important beings, why do 50 percent of them disappear, and we never have any knowledge of them?

MOLLY: Argument number two?

LEROY WALTERS: Early embryos can split into two.

MOLLY: As in twins.

LEROY WALTERS: Or two separate embryos can recombine ...

MOLLY: Into one embryo.

JAD: Right.

MOLLY: Like, before 14 days an embryo doesn't know if it's one embryo or if it's, like, gonna be one person or if it's gonna be two people. So as LeRoy put it, it doesn't have a ...

LEROY WALTERS: A biological identity.

MOLLY: And that happens right around 14 days.

LEROY WALTERS: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: Argument number three ...

LEROY WALTERS: The primitive streak appears.

JAD: The primitive streak appears?

LEROY WALTERS: The primitive streak is the first indication of a—an axis of the future body.

MOLLY: People see it as, like, a—the body starting to organize itself.

LEROY WALTERS: You might say it's the outline of the spinal cord that will develop later on.

JAD: It's the first hint of, like ...

MOLLY: Shape.

LEROY WALTERS: All of those seem to kind of converge around 14 days.

MOLLY: Eventually the committee decides to take LeRoy's suggestion and recommend that all research on human embryos be stopped at 14 days.

LEROY WALTERS: With high expectations, we submitted the report to Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Joseph Califano on May 4, 1979. And on July 19, 1979, before he could respond, Secretary Califano was fired by President Jimmy Carter.

MOLLY: It was part of a whole cabinet shake-up.

LEROY WALTERS: And so the report has been sitting on shelves, gathering dust. And there has never been a formal response.

MOLLY: It did end up becoming a guideline in the US. It's actually an international guideline, but we never actually needed it, because 14 days ...

LEROY WALTERS: That was so far beyond the capacity of researchers to culture early embryos, that it also seemed like a safe—a safe marker, a safe boundary.

MOLLY: Because—and this is the interesting thing ...

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: ... with IVF, we're familiar with, like, days zero, one, two, three, four, five, six, which is about the time they put the embryo into the mother.

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: And so nobody had ever really seen how an embryo develops from days seven through fourteen.

JAD: Oh, interesting.

MOLLY: You can't photograph it through the body for, like, various reasons. For one, no one ever knows they're pregnant that early. Like, when did you and your wife realize you were pregnant? It's like a month after the fertilization happens.

JAD: Yeah, it's funny. It's like when she—you, even if you're trying, you don't actually know for weeks until ...

MOLLY: Yeah. And it's so small that even if you did know, the way it attaches to the uterus, it sort of burrows in, and you kind of can't see it.

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: And at the same time, scientists are pretty sure that this is a very important moment in development and they just can't get to it.

ROBERT: Wait—wait a second. Life Magazine 50 years ago, published these gorgeous pictures of—of a fertilized cell, and then beautiful little baby with eyes, you know, just ...

MOLLY: Yeah, but the—that—they have pictures of sperms and eggs, then there's a blank spot until at least three and a half weeks. So that magazine spread ...

ROBERT: Oh, so—so Life didn't show the first few—the second or third ...

MOLLY: No.

ROBERT: Really?

MOLLY: Yes.

ROBERT: You—you're saying that there is a place in the development of the human being that no scientist has seen?

MOLLY: No.

ROBERT: Ever?

MOLLY: No.

ROBERT: Really?

MOLLY: Yeah.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: So this is this kind of period which in the textbook you will find described as a black box.

MOLLY: Which brings us to Magdalena.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: So I'm Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, at the University of Cambridge in the UK.

MOLLY: She for years, had been trying to figure out how to grow embryos during this period.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: But for those experiments ...

MOLLY: And the problem was at this point, the embryo is beginning to attach to the mother's uterus, and so it just need certain things from the mother. And if you try and grow it in a dish, it just shrivels up and dies.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Yes, yes. So at the time we were trying really scratch our heads and come up with the most enriching environment we could imagine.

MOLLY: Like, maybe I can, like, recreate that really warm, cozy home, but in a dish without the mom.

JAD: Interesting. So it's like experimenting. Like, what is the right bath that the growing embryo needs?

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: To sort of get what it needs.

MOLLY: Yeah. And they decided that, while they were still trying to figure it out, they would just do it on mice embryos first.

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: And so she started essentially just coming up with, like, chemistry concoctions. They started with the gel ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Which was of particular elasticity.

MOLLY: Sort of gloppy and gooey. And then they toss in a serum made from ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Human placentas.

MOLLY: Added some hormones.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Like progesterone.

MOLLY: Along with ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Fibroblast growth factors.

MOLLY: And of course a dash of ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Laminin fibronectin.

MOLLY: This sounds like it—like someone would sell this as, like, a face cream or something.

MOLLY: They even tried serum from ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Bat's placentas.

MOLLY: That actually really didn't work.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: That was not so good as the serum from the human placenta.

MOLLY: Oh, really?

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Yes.

MOLLY: For five years they put stuff in, they pulled stuff out, they tried everything, until they ended up with something that, at least on mice, seemed to work really well. And so they thought, "Okay, maybe it's time we try this with human embryos."

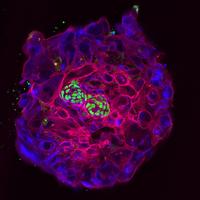

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: We took two embryos, just two human blastocysts ...

MOLLY: Put them in a dish with their chemical concoction and ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Amazingly ...

MOLLY: It worked.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: One of them did make it ...

MOLLY: To 13 days. The other one didn't.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: But one made it, right?

MOLLY: Suddenly they had an embryo that was growing happily into day eight. Day nine. Day 10. Day 11. And they were able to see all of these moments in human development that no one had ever seen before. And—and guess what Robert?

ROBERT: Yeah?

MOLLY: I got to see them, too.

ROBERT: You did?

MOLLY: I did! Do you want to come?

ROBERT: Of course, I want to come.

MOLLY: Okay, good.

ROBERT: We should go right now. I mean ...

MOLLY: We are gonna go, but we're gonna actually have to take a break first.

ROBERT: Oh, God.

MOLLY: So we'll be back in a bit.

ROBERT: Okay.

[LISTENER: Hi, this is Lizzie from Arlington, Texas. Radiolab is supported in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information about Sloan at www.sloan.org.]

ROBERT: Okay, we're back. I am Robert Krulwich.

MOLLY: I'm Molly Webster.

ROBERT: This is Radiolab. And today, the 14-day rule.

MOLLY: Last we left you, we had just met a woman who managed to grow a human embryo in a lab right up to the 14-day line.

ROBERT: And now we get to see it, right? That's what you promised.

MOLLY: Yes. Yes.

MOLLY: One earphone on, one earphone off. Good luck. Good luck.

MOLLY: Lucky enough for me, there is an embryology lab right here in New York. Rockefeller University.

MOLLY: Hi, how are you? It's nice to meet you.

MOLLY: Run by this guy.

ALI BRIVANLOU: So you're a radio scientist.

MOLLY: Ali Brivanlou.

MOLLY: Uh, I fake being a scientist, but ...

MOLLY: Ali's team, building off of Magdalena's work, they were also growing human embryos in the lab to the 14-day mark. So he invited me up to see them.

ALI BRIVANLOU: Today is—you would realize that your eyes are seeing something that no other human being has ever seen, except the group in this lab.

MOLLY: And obviously, Magda's lab.

MOLLY: Wait. How many people are in this lab that you think saw it?

ALI BRIVANLOU: I think we're a total of 25.

MOLLY: So then I'll be, like, 26?

MOLLY: So Ali has to step out of the room.

MOLLY: I'm excited. Thank you, Ali.

MOLLY: And he passes me off to the guy that runs, like, the human embryology research at the lab.

GIST CROFT: Gist Croft.

MOLLY: And a lab technician.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Cecilia Pellegrini.

MOLLY: Cecilia Pellegrini?

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Yes.

MOLLY: Okay.

MOLLY: We go into the lab.

MOLLY: [whispers] Walking through a cool lab. It's very big and everyone's looking at me.

MOLLY: Lots of benches and microscopes and people pipetting, and ...

MOLLY: So a fridge. There's a little sticky note on the fridge that says “Experiment 27 embryos here."

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: So we keep them in ...

MOLLY: And Cecilia pulls out, like, a plastic box. It has a blue bottom and, like, a white opaque top.

MOLLY: The lid just came off.

MOLLY: And inside, there was kind of like a microscope slide, and the embryos were attached to that. But there was condensation on it, so we had to wait, like, 10 minutes.

MOLLY: I feel weirdly nervous.

MOLLY: But eventually we, like, looked down into this, like, little square well.

MOLLY: Okay. It's, like, 10 millimeters by 10 millimeters, and it has a little bit of liquid in it.

MOLLY: And then inside that liquid ...

MOLLY: Wow, this is a human embryo!

JAD: How big is it? How big is an embryo?

MOLLY: Oh my God, it's so small!

JAD: [laughs] It's like we talk about 14 days, and in my mind I do imagine a tiny little human. Is it even human-like at that point?

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Tiny dot right there.

MOLLY: No. It's just a little white dot.

MOLLY: Holy crap, that's really small. That's like a grain of sand.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Yeah, it's about that size.

MOLLY: And it looks like—I kept also thinking that it looked like if you took a sheet of typing paper, and you took a pin and you poked a hole in the paper and a little pinpoint of light came through.

JAD: That's what it looks like?

MOLLY: It looks like that.

JAD: Huh.

MOLLY: I cannot believe that goes into a 5' 9" tall human being.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: So that was a day-12 embryo we were looking at with our naked eye, but Gist and Cecilia also took me over to this badass microscope.

MOLLY: What do I—I don't want to break anything.

GIST CROFT: Yeah, you're not gonna break it. I'll show you how to do it.

MOLLY: So we could look at a bunch of images and see the development of an embryo day by day, starting with ...

GIST CROFT: Day eight.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: You see right here, like, you have the embryo mass.

ROBERT: What are you—what does it look like?

MOLLY: It's ...

MOLLY: It looks very lunar to me.

MOLLY: Blown-out gray sphere that has, like, modeled surfaces. But inside of it are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of cells.

GIST CROFT: There's trophectoderm, primitive endoderm, and there's epiblast.

MOLLY: There were, like, three different types of cells, but to me it, like, looked like a simple structure. And then ...

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: This is the same embryo the next day.

MOLLY: Wait. Is this day nine? Oh, whoa! It looks totally different. So ...

MOLLY: It starts to get a little more complex.

GIST CROFT: Now we can see nuclei.

MOLLY: Is that what all those bright spots are?

GIST CROFT: Yeah. There's a nucleus. There's a nucleus.

MOLLY: Huh. Can we switch from nine to 10?

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: So what are those oil droplet looking things?

GIST CROFT: Those look like oil droplets, don't they?

MOLLY: Now there are these, like, spherical balls around the edges, and it could be any number of things but Gist thinks they might be fat, like lipid. And the embryo, it starts forming, like, the asymmetry, like you see things move to different areas of the cell.

GIST CROFT: It makes a hollow shell inside.

MOLLY: And then your inner gut cavity, that starts to form and ...

GIST CROFT: There's all of a sudden a new cell type we've never seen, the yolk sac trophectoderm cells.

MOLLY: So a totally new type of cell no one's ever seen before.

GIST CROFT: So we don't know where it comes from, and neither does anyone else.

MOLLY: And then ...

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Day 11.

MOLLY: I get excited every time you open one of them. Okay, day 11 ...

MOLLY: Day 11 didn't really, like, look that different to me.

GIST CROFT: Day 12.

MOLLY: Day 12 has a lot more going on.

GIST CROFT: That's the origin of the placenta.

MOLLY: Cool.

MOLLY: Day 13, there's all this brightness at the bottom in the upper left hand corner.

GIST CROFT: These could be epiblast cells.

MOLLY: Wait, remind me again. The epiblast is ...

GIST CROFT: That is the—the cell type from which the entire body eventually emerges.

MOLLY: Gist says those are the cells that all of the body comes from. Like, all the other stuff is mostly just support.

JAD: Oh, wow. So it's like the—it's like the primal, like, primordial cells.

MOLLY: It's the foundational cells.

JAD: Foundational cells.

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: Yeah.

GIST CROFT: So ...

MOLLY: So I actually got there on day 13 of the experiment. So all of the embryos were just sort of waiting to get to day 14. And so that was it.

GIST CROFT: So let's shut this down and get this guy back in the incubator.

MOLLY: And then I was just sort of spit back out into the real world.

JAD: Are they learning fantastically new amazing things based on this? Are they ...

MOLLY: Well, like the—the big takeaway that both of the groups had was that this embryo grew for another week without any maternal input. And it grew basically as it should have grown.

ALI BRIVANLOU: Which was mind-blowing to me and to all of my colleagues, that the human embryo will behave in a self-organizing manner in a complete absence of maternal inputs at least for 14 days.

MOLLY: Like, I think they always thought even if they got the chemistry right, there'd be some sort of system breakdown because it wasn't getting input from the mom.

JAD: Interesting.

MOLLY: I always, like, keep thinking of it as, like, the anti-Mother's Day message. The embryo doesn't need you. Happy Mother's Day! But the—the one pro—pro-mom thing is by the—by the end, in between day, like, 12 to 14, it became clear that it started needing maternal input.

JAD: I see. Like what? Do they know?

MOLLY: Well, so they—this is a part I thought was cool was, like, they saw that the embryo started forming tunnels and pathways for the mom to, like, infiltrate.

JAD: Oh!

MOLLY: So there were little tubes and pathways that formed where, like, nerve attachment could happen and, like, circulation. So it prepares itself in this week for the mom and the connection.

JAD: That's really cool. It's like—it's like hooking itself up to the network in a way.

MOLLY: I know. It's funny. It's like coming online as, like, a human being.

JAD: Coming online. Yeah, that's a good way to put it.

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: That's cool.

MOLLY: The other cool thing was Gist told me that right around day 10 along the edges of the embryo, this hormone shows up that your body doesn't have before, it's called, like, a gonadotropin. So you know when you take a pregnancy test, the thing it's reading is that hormone.

JAD: Oh, is that—he thinks, like, the embryo broadcasting?

MOLLY: Yes, it's like boom.

JAD: Boom. Boom.

MOLLY: Boom Boom. Like, out to the rest of the body. Like, "I'm here. I'm here. Look at this hormone!"

JAD: Wow, that's super cool.

MOLLY: What is it like to look through a microscope and see day eight when we've been stopped at day seven since the 1970s, or day nine or day ten?

ALI BRIVANLOU: It's hard to describe it. When people receive the digital image of the Hubble telescope, those first few eyes who are getting it in their screens, I guess it has to be something very similar to that. When I look inside of our own anatomy at the time where nobody knows that we even exist, is the same as looking at dimensions that we have never imagined we will ever see because we didn't even know they exist.

MOLLY: But then at day 14 you have to essentially embalm it. You, like, can make it stop growing and freeze in the place that it's at. They call it fixing.

ROBERT: But if they wanted to, could they go past 14 days?

MOLLY: Maybe. But Ali, he said that as they got closer to Day 14, they noticed changes in the embryo that made it clear that it started needing more than just the current bath that it was in.

JAD: Okay.

MOLLY: But like, and Brivanlou says this too, and Magdalena says this, it's like everyday feels like an accomplishment. You'll be like, "Oh my gosh, you grew another day!" And then you start, like, cheering it on. You're like, "Grow another day! Grow another day! Oh my gosh, you're at day 12!" And it becomes like you're, like, championing it, and then you're like, "Okay, stop. You're done."

JAD: Right.

MOLLY: And I felt like when I was standing there, I was like, "Oh that's abrupt, because I wanted it to grow, grow, grow, grow, grow. But obviously, I don't want it to grow, grow, grow too far. So I was like, "Go to day 15." Then I'm like, "Go to day 16." And then I'm like, "When does the joy in my voice stop?" Like this—eventually, I'm gonna—I'm gonna hit a point where I'm like, "That's uncomfortable."

JAD: Right.

ALI BRIVANLOU: This is something that touches us in the root of our own definition of our being and existence and individuality. It becomes a little bit like a Pandora box. So yes, you want to open it, but you have to be ready to see what's in it.

ROBERT: If technology has now moved it a whole 'nother week, so we can go for 14 days, maybe it's pretty soon you can go a whole 'nother week and then a whole 'nother week. Like, what—does that mean the rule's going to have to change?

MOLLY: That is the conversation that's happening right now. Basically, once this research was published, there were commentaries and articles and columns about what do we do about the 14-day rule? And there's conferences, there's a conference in Boston that's happening in the fall.

ROBERT: But what are your choices though? Like, you could choose ...

MOLLY: You could—could do any number of things. It depends on where you sort of throw down a biological or moral marker that you feel comfortable with. Like, you could keep it at 14 days and sort of keep it around, like, this idea of twinning and the primitive streak. You could move it a week out to, say, to day 21 when there's interesting sort of neural folds and divisions that are starting to happen in the brain. You could go to eight weeks. But it could also go back to zero.

ROBERT: Oh, so there's no consensus on ...

MOLLY: No. No, there's no consensus. And the scientists are the first to say, like, they don't want to make this decision. They just think, like, maybe we should have this conversation as a group, so the society decides, not us.

ALI BRIVANLOU: So yeah ...

MOLLY: But it's just like, if you say that, like, it's as amazing as, like, the Hubble telescope, how does it feel when you're like, "I've gotten this far, and now I have to end it?"

ALI BRIVANLOU: So that's the toughest question you're gonna ask me today. For me for sure, it was important to stop the experiment where there was still a message that we could convey that would not offend people. This is more than just science. One of the greatest challenge in reproductive biology, especially in human reproductive biology, is to make sure that you don't offend people's sense of identity, dignity, religion.

MOLLY: And so Ali, he finds himself trying to keep all of these different perspectives in his head all at once.

ALI BRIVANLOU: So for example, if the Catholic point of view is human origin is conception, then I have to respect also the Jewish point of view that says, "You know what? It's at heartbeat." I also have to respect the Muslim point of view about the origin of human life, which surprisingly for once seems to be similar to the Jewish point of view. It's also heartbeat. I also have to respect the Buddhist point of view. And what about the Hindus? The Buddhist says if you don't cut the umbilical cord, then you're not independent, you're not a human being. You don't call an organ a human being because it's attached to you. A Hindu says, "I don't know what you guys are talking about. There is no origin or end. We're circles within circles within circles. I'm a butterfly today. I'm going to die and come back as a tiger. I'm going to die and come back as a human, then come back as an elephant. What origin? A circle does not have an origin." So I am for the progress of science. I am for gaining knowledge. It's my job. It's the way I'm wired. As a human being, I satisfy our sense of curiosity. And there is nothing more curious to me than our own origin.

MOLLY: So then that would be like, you would love to know, like, what happens on day 21?

ALI BRIVANLOU: Absolutely. And I like to think that before I die, we will know what happens on day 21.

MOLLY: This episode was produced by Annie McEwen with help from Matt Kielty and Brenna Farrell and Simon Adler, and I actually think the entire Radiolab staff had something to do with this episode. So thanks guys. And I want to thank the research library at Georgetown University.

ROBERT: Thank you for listening.

MOLLY: See you later.

[ANSWERING MACHINE: To play the message, press 2.]

[LEROY WALTERS: This is LeRoy Walters. I'm a retired faculty member from Georgetown University, where I was part of the Kennedy Institute of Ethics and the philosophy department. Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad. Dylan Keefe is our Director of Sound Design. Soren Wheeler is Senior Editor. Jamie York is our Senior Producer. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Brenna Farrell, David Gebel, Matt Kielty, Robert Krulwich, Annie McEwen, Latif Nasser, Malissa O'Donnell, Arianne Wack and Molly Webster, with help from Nigar Fatali, Alexandra B. Young, Charu Sinha, Percia Verlin and W. Harry Fortuna. Our fact-checkers are Eva Dasher and Michelle Harris. That's it. Thanks. Bye.]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.