Aug 30, 2015

Transcript

ROBERT KRULWICH: So we want to finish the night with a salute to a guy who's been on our program and part of our family pretty much from the beginning, I have known him for more than 35 years. Early on when Radiolab started, I asked him if he'd help us out and send us a few story ideas. He didn't send us a few, he sent us bushels—tales of chemistry and medicine, hallucinations, music, people, so many extraordinary people that he knew or found or helped. Because the guy just doesn't run out. Dr. Oliver Sacks, neurologist, author.

[applause]

ROBERT: He's a guy who notices everything. He's deeply interested in everything that happens around him and to him. And tonight we're bringing him back on tape for what, alas, may be his final offering for us. As many of you know, Dr. Sacks recently was diagnosed with liver cancer. And he wrote about this in the New York Times. He said he plans to spend the time that he has left writing, being with friends, not doing interviews. But he did agree to share his thoughts exclusively with us tonight, for you gathered here, because he's one of our family.

ROBERT: So as I've done for decades now, I went over to his house in Manhattan with my mic, and I said to him ...

ROBERT: I just need to know what—what just happened. A month and a half ago you were fine, and then what?

OLIVER SACKS: At the beginning of the year, I was fine. On the 3rd of January, I felt a little queer and I passed some dark urine. I thought I had a little gallbladder attack and didn't pay that much attention, but thought I'd better get things checked. And the x-ray, which was expected only to show a couple of gallstones, showed hundreds of cysts in my liver. Although my doctor said he didn't know what these were and I would need further tests, I knew what they were. I said, "It's happened."

ROBERT: And he was right. The doctors eventually confirmed that a cancer that had been found in his eye nine years ago had spread to his liver

ROBERT: Were you frightened or relieved or consoled? Or what?

OLIVER SACKS: No, I think my first feeling was one of overwhelming sadness. There are all sorts of things I won't see and I won't do. One or two people have written to me, you know, consoling me, and said, "Well, we all die." But fuck it. It's not like, "We all die." It's like, "You have four months."

ROBERT: Has that—what is your prognosis at this moment? Because I know you had an ...

OLIVER SACKS: Well, it gets revised.

ROBERT: It depends, of course, on how the cancer responds to treatments, or how quickly it spreads.

OLIVER SACKS: So far, the metastases from my eye are only in my liver. I'm told they love liver. Actually, I love liver as well.

[laughter]

OLIVER SACKS: And one of the magical things I did was to go and have liver and onions soon after the diagnosis.

ROBERT: Oh, wow!

OLIVER SACKS: And thinking, "That liver looks better than mine, probably."

[laughter]

ROBERT: [laughs] See? This is what he's like. Instead of being frightened by the thing that's trying to kill him, he's thinking about loving liver and liver lovers, and looking for connections and wondering. He doesn't stop. He just notices it. Case in point, a few months ago his doctor said to him, "We're gonna run a line up your liver, and in effect, we're gonna try to shave off or starve some of the cancer cells, first on one side, then on the other, to see if we can give you a little more time." But they warned him ...

OLIVER SACKS: As the metastases die ,they put out various unpleasant chemicals.

ROBERT: That may exhaust you, tax your system badly.

OLIVER SACKS: And at one point ...

ROBERT: Shortly after the procedures.

OLIVER SACKS: ... I started talking a little strangely. And as I was talking, I was also writing. You will be the first person to see this.

ROBERT: So he showed me a notebook—and we're showing it to you in just a moment. You can see there is writing there on the left. He's writing a book, actually, a children's book about the elementary table, but as he was writing, if you look to the next page, if you can see that, it gets a little bit wobbly, the letters.

OLIVER SACKS: And then there was some crossing out there.

ROBERT: Yeah, I see the crossing out.

OLIVER SACKS: And then rather dramatically the writing changes.

ROBERT: Actually, there's a large slash across it and then it seems a little incoherent at the bottom.

OLIVER SACKS: Yes. Okay.

ROBERT: And then it turns to pure scribble.

OLIVER SACKS: That is delirium. It crept up on me. All this happened in the course of 10 minutes.

ROBERT: You see what he's doing here. He's figuring, "Okay, I'm writing at a constant speed. I know pretty much how fast I write, and so I can time this out. I can figure out exactly how long it took me to slip into delirium, and then out of this delirium." And he's doing this as a very, very sick man, "It's science all the time!"

OLIVER SACKS: If I had to write it out in a more medical way, I think this would form a lovely illustration. You put on a timeline of delirium, just coming like that.

ROBERT: Why aren't you more frightened? Like, unusual for any doctor and a man of science, you don't seem to worry at all when things become incoherent or strange. You're now showing it to me as it's like, "Ooh, how interesting? I was crazy here for a little bit."

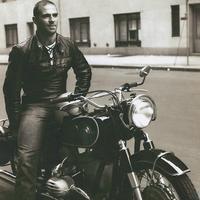

ROBERT: The truth is, Oliver is fascinated by what goes on in the human mind, no matter how strange he gets up there. And one time when he was a young resident in California driving his bike—and by the way, I should show you what he looked like back then when he was driving his bike. This, I think, it's him in New York, a kinda—you know?

ROBERT: In the '60s, he was also a champion weightlifter. They called them Dr. Squat. And in this picture that I'm showing you here, that's him raising 600 pounds in order to win a trophy. Like, this is a—he was a champ. And you can see more pictures like these because we have signed copies of Oliver's new memoir out for sale in the lobby. It's a pretty good book, too, by the way. So in any case, at this time in the 1960s, in addition to being all muscled out, Oliver was a serious recreational drug taker. And because he's Oliver, he was extremely curious about his highs, no matter how weird they were. One time, for example, he took 20 pills that he shouldn't have.

OLIVER SACKS: And then to my surprise, there was a spider on the wall which said, "Hello." It had a voice like Bertrand Russell.

ROBERT: A famous mathematician.

OLIVER SACKS: And it asked me a rather technical question as to whether Russell had exploded Frege's paradox. And we had this conversation.

ROBERT: You answered the spider?

OLIVER SACKS: Sure, I answered the spider.

ROBERT: You discussed Frege's paradox with the spider?

OLIVER SACKS: I did indeed. Because you trust your perceptions.

ROBERT: Okay.

OLIVER SACKS: Many years later, when I mentioned this to an entomologist friend at Cornell, the philosophical spider, he said, "Yes." He said, "I know the species."

[laughter]

ROBERT: So thinking Oliver's way, taking it all in, talking spiders, whatever, the generosity of his curiosity becomes profoundly moving and transformative when he's treating his patients. I want to tell one story here really quickly to demonstrate what I mean. Oliver once had a patient whom he called Mrs. OC. She was an old woman. She was 88 years old, living in a nursing home. And one night she was awakened, jarred awake by a loud sound.

[music]

ROBERT: It was a song. And she thought, "Well, somebody's left the radio on." But when she looked, the radio in the room was off, her roommate sound asleep, which was odd because the song was really loud. And after that, it was another song, and then another song.

ROBERT: And this is what she thought: "Well, maybe my roommate can't hear these songs because the songs are coming through the fillings in my teeth. I've heard that's possible." But no, her doctors told her, "This is something in your head. You need to see a neurologist." Which led her to Dr. Sacks. Now when he met Mrs. OC, she could barely hear him, the songs sung by the female voice were coming and coming. She was frightened and justifiably worried that she was going crazy. But Oliver said, "No, no, no. I'm gonna do some tests." And when he was done, he said he'd found a slight stroke or condition that had triggered 'musical epilepsy,' the sudden production of music in her brain. Now a normal doctor might say, "Okay, we've got the diagnosis," and he thought that the songs would probably fade and it would pass so they would be done. But Oliver did not stop. He doesn't stop.

ROBERT: He kept talking to her. She told him she was born in Ireland in the 1890s. Her father died before she was born, her mother when she was only five.

OLIVER SACKS: Orphaned, alone, she was sent to America to live with a rather forbidding maiden aunt. She had no conscious memory of the first five years of her life—no memory of her mother, of Ireland. She had always felt this as a keen and painful sadness, this lack of forgetting of the earliest, most precious years of her life.

ROBERT: So he asked her about the songs. "What are they like?" And Mrs. OC said, "Well, I think they're lullabies." "Can you sing them for me?" She did. And then after checking with—and I'm not sure who—Oliver figured out that these songs happened to be popular Irish ballads from the 1890s when Mrs. OC was a little baby. And that gave him an idea. Now what he does next isn't science. It isn't in any traditional way medicine. He just told her a story, and it goes like this. You know how nobody remembers anything that happens to you when you're one or two or three? Well, there was a theory once, not honored much today, but it said that those earliest memories get locked away deep in our brains in a special safe that we can never open. "So let's suppose, Mrs. OC, that your stroke by some crazy chance opened the lock that none of us can break and released those first memories in you, just for a little while. So that the voice you're listening to ...

[music]

ROBERT: ... maybe that isn't a radio voice. Let's say that it's your mother's voice. That's your missing mother. And so at the ripe old age of 88, you finally get to be back in your mother's arms. You get to be a baby again." And Mrs. OC thought about that and said, "Okay, it sort of fits."

OLIVER SACKS: "I'm an old woman with a stroke in an old people's home, but I feel I'm a child in Ireland again, I feel my mother's arms. I see her, I hear her voice singing.

[music]

ROBERT: Shortly thereafter, the songs began to fade, the pauses widened. Mrs. OC, who had been so frightened by this music in her head was now sorry to see the songs go. But it was Oliver who noticed how those songs had touched her, who noticed that the songs might become a comfort to her because that's what he does. He listens closely. He can hear another person's heart.

ROBERT: And this is really the profound puzzle for me of Oliver, because reading the new autobiography, you see that while he was so full of heart as a doctor in his own life and in the relationships that really mattered, it turns out he didn't get a whole lot of affection. He was for a long time, a lonely guy. I'd say he was very lonely. And he's talking about that now for the first time.

ROBERT: Let me talk about love for a minute. In this book, you tell the story of your very first love, a fellow by the name of Richard Selig. Can you just tell me what happened with him?

OLIVER SACKS: Yeah. He was a Rhodes scholar at Oxford, and a poet. And handsome and beautiful beyond belief. And I sort of fell for him, although I didn't say anything because I was very haunted by my mother's accusations.

ROBERT: What did your mother ...

OLIVER SACKS: Well, to go a couple of years back then, my father had opened a conversation that I was about to go to Oxford, a sort of father-son conversation. He said, "You don't seem to have many girlfriends." And I said, "No," wishing the conversation would stop. He said, "Something wrong with girls?" I said, "No, they're fine." "Perhaps you prefer boys." And I said, "Well, yes I do." I said, "I've never done anything, but I do." And ...

ROBERT: And you knew that then?

OLIVER SACKS: I knew that then. I had known it for six years, probably. Since I was 12. And I said, "Don't tell Ma. She won't be able to take it." But my father did tell my mother in the night, and the next morning she came down with, I somehow want to say a face of thunder and raged at me. And among other things said, "You're an abomination. I wish you had never been born." And then she suddenly shut up and said nothing for three days. And the matter was never mentioned again in her lifetime. And then two years later, I found myself for the first time in my life falling in love.

ROBERT: And this was the young guy, Richard. Oliver at the time was in college.

OLIVER SACKS: It was a very positive feeling, though I didn't know whether it was one which I dared express. But I did say so with my heart in my mouth to Richard.

ROBERT: What did you—do you remember what you said?

OLIVER SACKS: I said, "I'm in love with you." And Richard gripped me by the shoulders, and he said, "I know." He said, "But I'm not that way, but I love you in my own way." And I was glad I had said it. I'm glad that it had been received in such a warm, friendly way. I thought we might be friends for the rest of our lives, but then one day he came in to me. He said he'd been bothered by finding a lump in his groin.

ROBERT: And he was worried.

OLIVER SACKS: Could I have a look at it? And I looked at it and I felt it, and it was hard and tethered. It turned out to be a particularly malignant form of lymphoid tumor, what was called a lymphoma sarcoma. And he never spoke to me again after that. I don't know whether, since I'd been the first to recognize the ominous import, I don't know whether he saw me as a harbinger of death or a messenger of death, whatever.

ROBERT: But you were left with that silence?

OLIVER SACKS: Yeah.

ROBERT: Yeah.

ROBERT: A few years later, Oliver met a man named Mel. He was young, he was a sailor. Like Oliver, he was into weightlifting. They became close friends, and they began living together.

OLIVER SACKS: I adored him and was in love with him, and loved physical contact with him.

ROBERT: And they'd work out and they'd wrestle and ride motorcycles kind of tightly, and they never talked about what might or might not be happening between them. But one day they were together, and Oliver was giving Mel a back massage, which Mel often asked him to do.

OLIVER SACKS: And I loved doing that.

ROBERT: And Oliver says, sometimes he'd get a little, you know, excited.

OLIVER SACKS: And so long as I gave no explicit indication, it was okay. But one day, things went a bit too far and I got sort of—I went over the brink instead of just before the brink. Mel immediately sort of got up and had a shower and said, "I can't stay with you anymore." And I found that very cruel and upsetting and heartbreaking. And it made me feel I don't want to have anything to do with people. I mustn't fall in love. I cannot share lives with anyone again.

ROBERT: And he didn't share his life with anyone for a long, long time. In fact, he told me a story about something that happened to him maybe eight years ago.

OLIVER SACKS: I was just joining the faculty at Columbia, and I was having a sort of an interview. And at one point, the interviewer said to me, she said, "I have something rather private to ask you. Would you like Miss Edgar, your assistant, to leave?" And I said, "No, she's privy to all my affairs." And I then said, thinking she was going to ask me about sex, I said, "I haven't had any sex for 35 years."

ROBERT: [laughs]

OLIVER SACKS: In fact, she was going to ask me my social security number.

[laughter]

OLIVER SACKS: And she burst into laughter. She said, "Oh, you poor thing!" She said, "We must do something about it."

ROBERT: Well, the truth is Oliver didn't do anything about it because he didn't think he could. I mean, he'd chosen Richard, lost Richard, chosen Mel, lost Mel. There wasn't a point, he was thinking. And then finally—and who knows when or why these things happen to people, but a man came along who for the first time chose Oliver.

OLIVER SACKS: I had met Billy as I meet a number of people because I'd been sent a manuscript or a proof for a book. And an intimacy grew between us. I don't think I quite realized how deep it was, but then there was a particular episode in Christmas of '09 when he came up and in a sort of serious way he has, a serious careful way, he said, "I have conceived a deep love for you."

ROBERT: I have conceived a deep love for you?

OLIVER SACKS: Yes.

ROBERT: That's got a few extra words. "I have conceived ..."

OLIVER SACKS: Yes. Right. Okay

ROBERT: Was he scared to say, "I love you?"

OLIVER SACKS: No, he likes the English language.

[laughter]

OLIVER SACKS: I think it couldn't have been put more cautiously and yet more strongly. I think it was a beautiful way of putting it, and then I realized at that moment with his saying that I had conceived a deep love for him. And I—among other things, I thought, "Good God, it's happened again. And I'm in my 77th year."

ROBERT: That's amazing. 77.

OLIVER SACKS: "And what next?" And things basically have gone happily ever since. And surprisingly guiltlessly because then again, I'm not dealing with a 'what,' I'm dealing with a 'who.' I'm dealing with an individual. I'm not dealing with a condition defined by medicine or law.

ROBERT: So Oliver still doesn't know how much time he has left, but for the moment, as you can hear, his mind is totally intact. He's still writing. He has two books in addition to the one you'll find in the lobby that he's writing. And the children's book, a bunch of New Yorker stories in the last few months, and a New York Review of Books story. He's got energy to spare. So I want to do one last thing before we close. And this comes from yet another conversation I had with him. And it's a story I know Oliver would hate because he's not a capital-R "Religious" kind of guy. But he is somebody who definitely embraces mystery. And for a long time, he's been mystified by a color called indigo.

OLIVER SACKS: Indigo, which Newton had inserted between blue and violet. And no two people seem to agree as to what indigo was like. And so I built up a sort of chemical launchpad.

ROBERT: Meaning he took a lot of drugs.

[laughter]

OLIVER SACKS: A base of amphetamine for general arousal, then some acid and a little cannabis. And when I was sufficiently stoned, I said, "I want to see indigo now." As if in reply and as if thrown by a giant paintbrush, there appeared a huge trembling pear-shaped blob of what I instantly realized was pure indigo on the white floor in front of me. It had a wonderful luminosity. And in particular, although I am not a religious person, I thought, "This is the color of heaven." And I leaned towards it in a sort of ecstasy, and then suddenly it disappeared.

ROBERT: And he says he had one more moment like that—this time no drugs. He was in a museum, staring at an Egyptian artifact. He sees this brilliant color back again, just for a beat.

OLIVER SACKS: I was given five tantalizing seconds of radiant, ineffable beauty.

ROBERT: And then, again, it vanished.

OLIVER SACKS: And that was in 1965, and I've never seen indigo since.

ROBERT: But who knows, you know? Someday, I like to think Dr. Sacks may get to see that color again.

[applause]

[music]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.