Dec 7, 2022

Transcript

MOLLY WEBSTER: Hey, listeners. Before we start today's show, we want you to know that today's episode contains discussion of abortions and may not be suitable for young or sensitive listeners.

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

MOLLY: So I like medical stories.

JAD ABUMRAD: Mm-hmm. This I know about you.

MOLLY: This you know. And I read this website called StatNews.com, which does sort of really—it's like a new website out of Boston.

JAD: It's new, right?

MOLLY: I mean, basically it's this collection of really amazing, like, medical reporters, and I will click on stories that look interesting. And there was one about we've just grown embryos—human embryos for a long time in a lab.

JAD: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: And that was when I read the phrase "The 14-day rule" for the first time, and it was that apparently there's this thing that you can't grow an embryo in a lab past 14 days.

JAD: Huh.

MOLLY: Which I didn't even know you could grow an embryo in a lab at all.

JAD: Right, right.

MOLLY: Or—or that people were. Or that—I mean, I guess I knew IVF happened.

JAD: Sure.

MOLLY: Like test tube babies.

JAD: How long if—in the average IVF situation, how long is an embryo in a dish for?

MOLLY: And then I realized I didn't actually even know that, either. So then I just spun out. So like, the whole article was just interesting to me because I was like ...

MOLLY: I don't know about any of this.

JAD: Right, right.

MOLLY: I'm Molly Webster.

ROBERT KRULWICH: Oh, and I'm Robert Krulwich. This is Radiolab.

MOLLY: And today on Radiolab. We're gonna zip down a wormhole into another universe, and Robert you're coming with me.

ROBERT: Okay. What—tell me about this universe before I buy a ticket.

MOLLY: The universe—oh, okay. You're going to want to buy a ticket, because in this universe are twins and souls and mice and something called the primitive streak. And they're all gathered together around a certain rule.

ROBERT: And remind me again what the rule was?

MOLLY: Well, so you know how you can fertilize an egg? You get an egg and a sperm and you put them together.

ROBERT: Yes.

MOLLY: Fertilizes the egg?

ROBERT: Right.

MOLLY: And then the egg—the fertilized egg, it multiplies, multiplies, cell divides.

ROBERT: Right.

MOLLY: So a scientist could take it to watch it grow to learn about human development. But then they have to stop at day 14. That's the rule.

ROBERT: Is this a medical kind of thing? Or a science limitation?

MOLLY: It is—it's medical—it's all those things. It's medical and it's science and there's, like, philosophy and ethics, and obviously religion. And ...

ROBERT: And that's the ticket I'm buying, huh?

MOLLY: Yeah, you're buying it now, right?

ROBERT: I see. The whole shebang.

LEROY WALTERS: I have water.

MOLLY: Okay.

LEROY WALTERS: I'll take a sip.

MOLLY: Okay.

MOLLY: And we're going to begin with this guy, LeRoy Walters.

LEROY WALTERS: Okay.

MOLLY: He was an ethicist at Georgetown University, now retired. And to me, he is sort of the father of the 14-day rule.

LEROY WALTERS: I never—I never thought of myself as the father of the 14-day rule.

MOLLY: But he is. He totally is.

LEROY WALTERS: Well, we shouldn't forget the context of '73.

MOLLY: All right. So 1973, Leroy has recently graduated with a doctorate in ethics from Yale University and he's settling into his job. And at the time, medicine and ethics were on sort of a collision course.

LEROY WALTERS: Yes, yes. Mm-hmm.

[NEWS CLIP: Good evening.]

MOLLY: January, 1973.

[NEWS CLIP: In a landmark ruling, the Supreme Court today legalized abortion.]

MOLLY: Roe v. Wade happens.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, politician: It is clear, at least under present law, that an unborn fetus is not a person within the meaning of the Constitution.]

MOLLY: But just six months after that decision ...

[NEWS CLIP: The issue of fetuses and research done with them ...]

LEROY WALTERS: Fetal research became a hot topic.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, politician: Some of the testimony in here is shocking.]

MOLLY: There were news reports ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, politician: Of butchering and cutting up ...]

MOLLY: About dissecting fetuses, even an instance of decapitating fetuses.

JAD: Oh, man.

MOLLY: And then around the same time ...

[NEWS CLIP: ... used as human guinea pigs.]

LEROY WALTERS: Research involving human beings.

[NEWS CLIP: The controversial Tuskegee syphilis study ...]

MOLLY: News reports of the syphilis studies that were done on African-American men without their knowledge.

LEROY WALTERS: There was the sterilization of ...

[NEWS CLIP: Two daughters had been sterilized without their informed consent ...]

LEROY WALTERS: ... women with intellectual disabilities.

[NEWS CLIP: ... experiments in genetic research.]

MOLLY: Genetic engineering was coming into its own. You have all these questions swirling about like, how we feel about the human body, whether or not we want to experiment on it? What do we protect, and what don't we protect? It's just sort of this whirlwind, and ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: You are about to see a historic birth ...]

MOLLY: Then most relevant for our story ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: We are going to deliver her by Cesarean section.]

MOLLY: On July 25, 1978 ...

LEROY WALTERS: Scientists in the UK ...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, doctor: We are now incising the uterus itself.]

LEROY WALTERS: Produced a child with the aid of in vitro fertilization.

MOLLY: The first baby that was born from an embryo that was grown inside a tube.

LEROY WALTERS: Baby Louise Brown.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, doctor: Baby's not opened her eyes yet.]

LEROY WALTERS: Everyone in the world was fascinated, but there were people who predicted doom.

MOLLY: What was the doom?

LEROY WALTERS: That in vitro fertilization would lead to reproduction as a form of manufacture.

MOLLY: So the government was grappling with, we need more regulations or we need as a country to think about, like, what the ethical guidelines are.

LEROY WALTERS: Right. So ...

[NEWS CLIP: The Department of Health, Education and Welfare ...]

MOLLY: And they put together something called the Ethics Advisory Board.

[NEWS CLIP: The panel of doctors, laymen, academics ...]

MOLLY: Even a Jesuit priest.

[NEWS CLIP: To consider ...]

[NEWS CLIP: ... some fundamental moral and ethical questions ...]

[NEWS CLIP: ... questions involved in test tube human fertilization.]

[NEWS CLIP: Its meetings and discussions open today.]

MOLLY: Now, as part of those meetings, the board will call on these expert witnesses. And one of those witnesses was our Boy LeRoy.

LEROY WALTERS: Right. The staff director ...

MOLLY: And they asked LeRoy, like, ethically tell us what we should be thinking about when it comes to embryos?

LEROY WALTERS: And how we are to regard them.

MOLLY: And he says, "Well, there's a spectrum. And on the one side, you could argue ...

LEROY WALTERS: ... that human embryos should be protected from the time of fertilization forward.

MOLLY: We shouldn't even be growing embryos in a lab at all.

LEROY WALTERS: But ...

MOLLY: Then there's the other side.

LEROY WALTERS: ... the most permissive position was that research could be done until about eight weeks ...

MOLLY: Because ...

LEROY WALTERS: A fetus at about eight weeks can have a reflex response to a stimulus.

JAD: Hmm.

LEROY WALTERS: And then ...

MOLLY: At some point a committee member turns to LeRoy and she says, where would you draw the line? He pauses and he says, "Well ..."

LEROY WALTERS: I would say for me, 14 days.

ROBERT: Why 14?

MOLLY: Well, LeRoy had a couple different arguments. For one, before 14 days ...

LEROY WALTERS: About 50 percent of early human embryos are simply sluffed off.

MOLLY: They're just sort of shed from the woman's uterus.

LEROY WALTERS: And don't develop further.

MOLLY: So the thinking was, if we're already losing 50 percent of them naturally ...

LEROY WALTERS: We don't have strong moral obligations toward early human embryos.

JAD: I see.

LEROY WALTERS: You can even pose it as a metaphysical question. If these are important beings, why do 50 percent of them disappear, and we never have any knowledge of them?

MOLLY: Argument number two?

LEROY WALTERS: Early embryos can split into two.

MOLLY: As in twins.

LEROY WALTERS: Or two separate embryos can recombine ...

MOLLY: Into one embryo.

JAD: Right.

MOLLY: Like, before 14 days an embryo doesn't know if it's one embryo or if it's, like, gonna be one person or if it's gonna be two people. So as LeRoy put it, it doesn't have a ...

LEROY WALTERS: A biological identity.

MOLLY: And that happens right around 14 days.

LEROY WALTERS: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: Argument number three ...

LEROY WALTERS: The primitive streak appears.

JAD: The primitive streak appears?

LEROY WALTERS: The primitive streak is the first indication of a—an axis of the future body.

MOLLY: People see it as, like, a—the body starting to organize itself.

LEROY WALTERS: You might say it's the outline of the spinal cord that will develop later on.

JAD: It's the first hint of, like ...

MOLLY: Shape.

LEROY WALTERS: All of those seem to kind of converge around 14 days.

MOLLY: Eventually the committee decides to take LeRoy's suggestion and recommend that all research on human embryos be stopped at 14 days.

LEROY WALTERS: With high expectations, we submitted the report to Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare Joseph Califano on May 4, 1979. And on July 19, 1979, before he could respond, Secretary Califano was fired by President Jimmy Carter.

MOLLY: It was part of a whole cabinet shake-up.

LEROY WALTERS: And so the report has been sitting on shelves, gathering dust. And there has never been a formal response.

MOLLY: It did end up becoming a guideline in the US. It's actually an international guideline, but we never actually needed it, because 14 days ...

LEROY WALTERS: That was so far beyond the capacity of researchers to culture early embryos, that it also seemed like a safe—a safe marker, a safe boundary.

MOLLY: Because—and this is the interesting thing ...

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: ... with IVF, we're familiar with, like, days zero, one, two, three, four, five, six, which is about the time they put the embryo into the mother.

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: And so nobody had ever really seen how an embryo develops from days seven through fourteen.

JAD: Oh, interesting.

MOLLY: You can't photograph it through the body for, like, various reasons. For one, no one ever knows they're pregnant that early. Like, when did you and your wife realize you were pregnant? It's like a month after the fertilization happens.

JAD: Yeah, it's funny. It's like when she—you, even if you're trying, you don't actually know for weeks until ...

MOLLY: Yeah. And it's so small that even if you did know, the way it attaches to the uterus, it sort of burrows in, and you kind of can't see it.

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: And at the same time, scientists are pretty sure that this is a very important moment in development and they just can't get to it.

ROBERT: Wait—wait a second. Life Magazine 50 years ago, published these gorgeous pictures of—of a fertilized cell, and then beautiful little baby with eyes, you know, just ...

MOLLY: Yeah, but the—that—they have pictures of sperms and eggs, then there's a blank spot until at least three and a half weeks. So that magazine spread ...

ROBERT: Oh, so—so Life didn't show the first few—the second or third ...

MOLLY: No.

ROBERT: Really?

MOLLY: Yes.

ROBERT: You—you're saying that there is a place in the development of the human being that no scientist has seen?

MOLLY: No.

ROBERT: Ever?

MOLLY: No.

ROBERT: Really?

MOLLY: Yeah.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: So this is this kind of period which in the textbook you will find described as a black box.

MOLLY: Which brings us to Magdalena.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: So I'm Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, at the University of Cambridge in the UK.

MOLLY: She for years, had been trying to figure out how to grow embryos during this period.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: But for those experiments ...

MOLLY: And the problem was at this point, the embryo is beginning to attach to the mother's uterus, and so it just need certain things from the mother. And if you try and grow it in a dish, it just shrivels up and dies.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Yes, yes. So at the time we were trying really scratch our heads and come up with the most enriching environment we could imagine.

MOLLY: Like, maybe I can, like, recreate that really warm, cozy home, but in a dish without the mom.

JAD: Interesting. So it's like experimenting. Like, what is the right bath that the growing embryo needs?

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: To sort of get what it needs.

MOLLY: Yeah. And they decided that, while they were still trying to figure it out, they would just do it on mice embryos first.

JAD: Uh-huh.

MOLLY: And so she started essentially just coming up with, like, chemistry concoctions. They started with the gel ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Which was of particular elasticity.

MOLLY: Sort of gloppy and gooey. And then they toss in a serum made from ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Human placentas.

MOLLY: Added some hormones.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Like progesterone.

MOLLY: Along with ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Fibroblast growth factors.

MOLLY: And of course a dash of ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Laminin fibronectin.

MOLLY: This sounds like it—like someone would sell this as, like, a face cream or something.

MOLLY: They even tried serum from ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Bat's placentas.

MOLLY: That actually really didn't work.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: That was not so good as the serum from the human placenta.

MOLLY: Oh, really?

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Yes.

MOLLY: For five years they put stuff in, they pulled stuff out, they tried everything, until they ended up with something that, at least on mice, seemed to work really well. And so they thought, "Okay, maybe it's time we try this with human embryos."

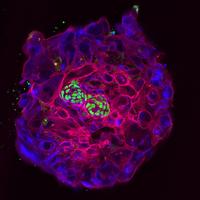

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: We took two embryos, just two human blastocysts ...

MOLLY: Put them in a dish with their chemical concoction and ...

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: Amazingly ...

MOLLY: It worked.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: One of them did make it ...

MOLLY: To 13 days. The other one didn't.

MAGDALENA ZERNICKA-GOETZ: But one made it, right?

MOLLY: Suddenly they had an embryo that was growing happily into day eight. Day nine. Day 10. Day 11. And they were able to see all of these moments in human development that no one had ever seen before. And—and guess what Robert?

ROBERT: Yeah?

MOLLY: I got to see them, too.

ROBERT: You did?

MOLLY: I did! Do you want to come?

ROBERT: Of course, I want to come.

MOLLY: Okay, good.

ROBERT: We should go right now. I mean ...

MOLLY: We are gonna go, but we're gonna actually have to take a break first.

ROBERT: Oh, God.

MOLLY: So we'll be back in a bit.

ROBERT: Okay.

ROBERT: Okay, we're back. I am Robert Krulwich.

MOLLY: I'm Molly Webster.

ROBERT: This is Radiolab. And today, the 14-day rule.

MOLLY: Last we left you, we had just met a woman who managed to grow a human embryo in a lab right up to the 14-day line.

ROBERT: And now we get to see it, right? That's what you promised.

MOLLY: Yes. Yes.

MOLLY: One earphone on, one earphone off. Good luck. Good luck.

MOLLY: Lucky enough for me, there is an embryology lab right here in New York. Rockefeller University.

MOLLY: Hi, how are you? It's nice to meet you.

MOLLY: Run by this guy.

ALI BRIVANLOU: So you're a radio scientist.

MOLLY: Ali Brivanlou.

MOLLY: Uh, I fake being a scientist, but ...

MOLLY: Ali's team, building off of Magdalena's work, they were also growing human embryos in the lab to the 14-day mark. So he invited me up to see them.

ALI BRIVANLOU: Today is—you would realize that your eyes are seeing something that no other human being has ever seen, except the group in this lab.

MOLLY: And obviously, Magda's lab.

MOLLY: Wait. How many people are in this lab that you think saw it?

ALI BRIVANLOU: I think we're a total of 25.

MOLLY: So then I'll be, like, 26?

MOLLY: So Ali has to step out of the room.

MOLLY: I'm excited. Thank you, Ali.

MOLLY: And he passes me off to the guy that runs, like, the human embryology research at the lab.

GIST CROFT: Gist Croft.

MOLLY: And a lab technician.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Cecilia Pellegrini.

MOLLY: Cecilia Pellegrini?

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Yes.

MOLLY: Okay.

MOLLY: We go into the lab.

MOLLY: [whispers] Walking through a cool lab. It's very big and everyone's looking at me.

MOLLY: Lots of benches and microscopes and people pipetting, and ...

MOLLY: So a fridge. There's a little sticky note on the fridge that says “Experiment 27 embryos here."

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: So we keep them in ...

MOLLY: And Cecilia pulls out, like, a plastic box. It has a blue bottom and, like, a white opaque top.

MOLLY: The lid just came off.

MOLLY: And inside, there was kind of like a microscope slide, and the embryos were attached to that. But there was condensation on it, so we had to wait, like, 10 minutes.

MOLLY: I feel weirdly nervous.

MOLLY: But eventually we, like, looked down into this, like, little square well.

MOLLY: Okay. It's, like, 10 millimeters by 10 millimeters, and it has a little bit of liquid in it.

MOLLY: And then inside that liquid ...

MOLLY: Wow, this is a human embryo!

JAD: How big is it? How big is an embryo?

MOLLY: Oh my God, it's so small!

JAD: [laughs] It's like we talk about 14 days, and in my mind I do imagine a tiny little human. Is it even human-like at that point?

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Tiny dot right there.

MOLLY: No. It's just a little white dot.

MOLLY: Holy crap, that's really small. That's like a grain of sand.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Yeah, it's about that size.

MOLLY: And it looks like—I kept also thinking that it looked like if you took a sheet of typing paper, and you took a pin and you poked a hole in the paper and a little pinpoint of light came through.

JAD: That's what it looks like?

MOLLY: It looks like that.

JAD: Huh.

MOLLY: I cannot believe that goes into a 5' 9" tall human being.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: So that was a day-12 embryo we were looking at with our naked eye, but Gist and Cecilia also took me over to this badass microscope.

MOLLY: What do I—I don't want to break anything.

GIST CROFT: Yeah, you're not gonna break it. I'll show you how to do it.

MOLLY: So we could look at a bunch of images and see the development of an embryo day by day, starting with ...

GIST CROFT: Day eight.

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: You see right here, like, you have the embryo mass.

ROBERT: What are you—what does it look like?

MOLLY: It's ...

MOLLY: It looks very lunar to me.

MOLLY: Blown-out gray sphere that has, like, modeled surfaces. But inside of it are hundreds and hundreds and hundreds of cells.

GIST CROFT: There's trophectoderm, primitive endoderm, and there's epiblast.

MOLLY: There were, like, three different types of cells, but to me it, like, looked like a simple structure. And then ...

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: This is the same embryo the next day.

MOLLY: Wait. Is this day nine? Oh, whoa! It looks totally different. So ...

MOLLY: It starts to get a little more complex.

GIST CROFT: Now we can see nuclei.

MOLLY: Is that what all those bright spots are?

GIST CROFT: Yeah. There's a nucleus. There's a nucleus.

MOLLY: Huh. Can we switch from nine to 10?

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: So what are those oil droplet looking things?

GIST CROFT: Those look like oil droplets, don't they?

MOLLY: Now there are these, like, spherical balls around the edges, and it could be any number of things but Gist thinks they might be fat, like lipid. And the embryo, it starts forming, like, the asymmetry, like you see things move to different areas of the cell.

GIST CROFT: It makes a hollow shell inside.

MOLLY: And then your inner gut cavity, that starts to form and ...

GIST CROFT: There's all of a sudden a new cell type we've never seen, the yolk sac trophectoderm cells.

MOLLY: So a totally new type of cell no one's ever seen before.

GIST CROFT: So we don't know where it comes from, and neither does anyone else.

MOLLY: And then ...

CECILIA PELLEGRINI: Day 11.

MOLLY: I get excited every time you open one of them. Okay, day 11 ...

MOLLY: Day 11 didn't really, like, look that different to me.

GIST CROFT: Day 12.

MOLLY: Day 12 has a lot more going on.

GIST CROFT: That's the origin of the placenta.

MOLLY: Cool.

MOLLY: Day 13, there's all this brightness at the bottom in the upper left hand corner.

GIST CROFT: These could be epiblast cells.

MOLLY: Wait, remind me again. The epiblast is ...

GIST CROFT: That is the—the cell type from which the entire body eventually emerges.

MOLLY: Gist says those are the cells that all of the body comes from. Like, all the other stuff is mostly just support.

JAD: Oh, wow. So it's like the—it's like the primal, like, primordial cells.

MOLLY: It's the foundational cells.

JAD: Foundational cells.

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: Yeah.

GIST CROFT: So ...

MOLLY: So I actually got there on day 13 of the experiment. So all of the embryos were just sort of waiting to get to day 14. And so that was it.

GIST CROFT: So let's shut this down and get this guy back in the incubator.

MOLLY: And then I was just sort of spit back out into the real world.

JAD: Are they learning fantastically new amazing things based on this? Are they ...

MOLLY: Well, like the—the big takeaway that both of the groups had was that this embryo grew for another week without any maternal input. And it grew basically as it should have grown.

ALI BRIVANLOU: Which was mind-blowing to me and to all of my colleagues, that the human embryo will behave in a self-organizing manner in a complete absence of maternal inputs at least for 14 days.

MOLLY: Like, I think they always thought even if they got the chemistry right, there'd be some sort of system breakdown because it wasn't getting input from the mom.

JAD: Interesting.

MOLLY: I always, like, keep thinking of it as, like, the anti-Mother's Day message. The embryo doesn't need you. Happy Mother's Day! But the—the one pro—pro-mom thing is by the—by the end, in between day, like, 12 to 14, it became clear that it started needing maternal input.

JAD: I see. Like what? Do they know?

MOLLY: Well, so they—this is a part I thought was cool was, like, they saw that the embryo started forming tunnels and pathways for the mom to, like, infiltrate.

JAD: Oh!

MOLLY: So there were little tubes and pathways that formed where, like, nerve attachment could happen and, like, circulation. So it prepares itself in this week for the mom and the connection.

JAD: That's really cool. It's like—it's like hooking itself up to the network in a way.

MOLLY: I know. It's funny. It's like coming online as, like, a human being.

JAD: Coming online. Yeah, that's a good way to put it.

MOLLY: Yeah.

JAD: That's cool.

MOLLY: The other cool thing was Gist told me that right around day 10 along the edges of the embryo, this hormone shows up that your body doesn't have before, it's called, like, a gonadotropin. So you know when you take a pregnancy test, the thing it's reading is that hormone.

JAD: Oh, is that—he thinks, like, the embryo broadcasting?

MOLLY: Yes, it's like boom.

JAD: Boom. Boom.

MOLLY: Boom Boom. Like, out to the rest of the body. Like, "I'm here. I'm here. Look at this hormone!"

JAD: Wow, that's super cool.

MOLLY: What is it like to look through a microscope and see day eight when we've been stopped at day seven since the 1970s, or day nine or day ten?

ALI BRIVANLOU: It's hard to describe it. When people receive the digital image of the Hubble telescope, those first few eyes who are getting it in their screens, I guess it has to be something very similar to that. When I look inside of our own anatomy at the time where nobody knows that we even exist, is the same as looking at dimensions that we have never imagined we will ever see because we didn't even know they exist.

MOLLY: But then at day 14 you have to essentially embalm it. You, like, can make it stop growing and freeze in the place that it's at. They call it fixing.

ROBERT: But if they wanted to, could they go past 14 days?

MOLLY: Maybe. But Ali, he said that as they got closer to Day 14, they noticed changes in the embryo that made it clear that it started needing more than just the current bath that it was in.

JAD: Okay.

MOLLY: But like, and Brivanlou says this too, and Magdalena says this, it's like everyday feels like an accomplishment. You'll be like, "Oh my gosh, you grew another day!" And then you start, like, cheering it on. You're like, "Grow another day! Grow another day! Oh my gosh, you're at day 12!" And it becomes like you're, like, championing it, and then you're like, "Okay, stop. You're done."

JAD: Right.

MOLLY: And I felt like when I was standing there, I was like, "Oh that's abrupt, because I wanted it to grow, grow, grow, grow, grow. But obviously, I don't want it to grow, grow, grow too far. So I was like, "Go to day 15." Then I'm like, "Go to day 16." And then I'm like, "When does the joy in my voice stop?" Like this—eventually, I'm gonna—I'm gonna hit a point where I'm like, "That's uncomfortable."

JAD: Right.

ALI BRIVANLOU: This is something that touches us in the root of our own definition of our being and existence and individuality. It becomes a little bit like a Pandora box. So yes, you want to open it, but you have to be ready to see what's in it.

ROBERT: If technology has now moved it a whole 'nother week, so we can go for 14 days, maybe it's pretty soon you can go a whole 'nother week and then a whole 'nother week. Like, what—does that mean the rule's going to have to change?

MOLLY: That is the conversation that's happening right now. Basically, once this research was published, there were commentaries and articles and columns about what do we do about the 14-day rule? And there's conferences, there's a conference in Boston that's happening in the fall.

ROBERT: But what are your choices though? Like, you could choose ...

MOLLY: You could—could do any number of things. It depends on where you sort of throw down a biological or moral marker that you feel comfortable with. Like, you could keep it at 14 days and sort of keep it around, like, this idea of twinning and the primitive streak. You could move it a week out to, say, to day 21 when there's interesting sort of neural folds and divisions that are starting to happen in the brain. You could go to eight weeks. But it could also go back to zero.

ROBERT: Oh, so there's no consensus on ...

MOLLY: No. No, there's no consensus. And the scientists are the first to say, like, they don't want to make this decision. They just think, like, maybe we should have this conversation as a group, so the society decides, not us.

ALI BRIVANLOU: So yeah ...

MOLLY: But it's just like, if you say that, like, it's as amazing as, like, the Hubble telescope, how does it feel when you're like, "I've gotten this far, and now I have to end it?"

ALI BRIVANLOU: So that's the toughest question you're going to ask me today. For me for sure, it was important to stop the experiment where there was still a message that we could convey that would not offend people. This is more than just science. One of the greatest challenge in reproductive biology, especially in human reproductive biology, is to make sure that you don't offend people's sense of identity, dignity, religion.

MOLLY: And so Ali, he finds himself trying to keep all of these different perspectives in his head all at once.

ALI BRIVANLOU: So for example, if the Catholic point of view is human origin is conception, then I have to respect also the Jewish point of view that says, "You know what? It's at heartbeat." I also have to respect the Muslim point of view about the origin of human life, which surprisingly for once seems to be similar to the Jewish point of view. It's also heartbeat. I also have to respect the Buddhist point of view. And what about the Hindus? The Buddhist says if you don't cut the umbilical cord, then you're not independent, you're not a human being. You don't call an organ a human being because it's attached to you. A Hindu says, "I don't know what you guys are talking about. There is no origin or end. We're circles within circles within circles. I'm a butterfly today. I'm going to die and come back as a tiger. I'm going to die and come back as a human, then come back as an elephant. What origin? A circle does not have an origin." So I am for the progress of science. I am for gaining knowledge. It's my job. It's the way I'm wired. As a human being, I satisfy our sense of curiosity. And there is nothing more curious to me than our own origin.

MOLLY: So then that would be like, you would love to know, like, what happens on day 21?

ALI BRIVANLOU: Absolutely. And I like to think that before I die, we will know what happens on day 21.

ROBERT: Thank you, Molly.

MOLLY: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: Since we first reported this story in 2016, the 14-day rule has actually been relaxed. An international body of scientists and thinkers have suggested that embryonic research beyond 14 days can now be considered on a case-by-case basis. Here at the show, we're following the changes and plan to update you with more very soon.

MOLLY: This episode was produced by Annie McEwen with help from Matt Kielty and Brenna Farrell and Simon Adler, and I actually think the entire Radiolab staff had something to do with this episode. So thanks guys. And I want to thank the research library at Georgetown University.

MOLLY: Coming up, we move to a very different story in the world of reproduction, that of medical abortions, aka the abortion pills. We're gonna look at how they were developed, new science around the technology, and consider how COVID might be changing everything. That is after the break.

[LISTENER: Hi, this is Jeremiah Barba, and I'm calling from San Francisco, California. Leadership support for Radiolab's science programming is provided by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, Science Sandbox, a Simons Foundation initiative, and the John Templeton Foundation. Foundational support for Radiolab was provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.]

LULU MILLER: Hi, I'm Lulu Miller.

LATIF NASSER: I'm Latif Nasser.

LULU: This is Radiolab.

LATIF: And for the last five or so months in this country, but I mean, really the last 50 years in this country, abortion has been in the news constantly in this one very specific way that you are no doubt familiar with. Two camps: one wants to restrict abortion, one wants to open it up. And they just battle back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.

LULU: But it turns out that all the while, there was another story unfolding, a scientific story. And it's one that a lot of people were not paying attention to—us included. It totally caught us off guard when we heard it, and so that is the story we're gonna tell today. It comes to us from contributing editor ...

AVIR MITRA: Hey, hey!

LULU: ... and ER doctor Avir Mitra.

AVIR: Boom. Here we go.

LULU: Alongside ...

MOLLY: Bahbahbahbahbah. Hello!

LULU: Our very own senior correspondent Molly Webster.

MOLLY: I don't know. I was just gonna say Avir, you start.

AVIR: [laughs] Okay.

MOLLY: Avir's gonna tell you a story.

AVIR: Yeah.

LULU: I love an Avir story.

AVIR: All right. Cool.

LULU: And we should say before we get rolling, this story talks about abortion and has some kind of graphic descriptions, so if you don't wanna hear that today, this is a good one to skip.

AVIR: Right. So, I guess this one started because for—okay, for me growing up, my mom, she's a OB/GYN, and I just remember her telling me about stories of her performing abortions back in her day. This would've been like the late '70s. So ...

LATIF: Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. I'm just picturing, like, muppet baby Avir.

LULU: [laughs]

LATIF: ... like, even before you were a doctor, your mom would tell you doctor stories?

AVIR: Yeah, I just grew up around so many medical stories—both my parents are doctors—that we talk about things at the dinner table that a normal family would be horrified, they would be actively vomiting and I'm just like, "Oh yeah, pass—you know, pass the salt, please." So basically, you know, when she would talk to me about these procedures, they were pretty invasive. Like, it was not a small deal, if that makes sense.

LATIF: Right.

AVIR: And even now in a hospital or clinic, it's pretty safe, but it's still something we take seriously. I mean, it's safe because we take it seriously.

LATIF: Mm-hmm.

AVIR: So for the last couple months, ever since the Supreme Court decision about abortion, I’ve been thinking about, like, what is this gonna mean for us in the emergency department ...

LULU: Hmm.

AVIR: ... now that we're living in this post-Roe world? 'Cause you know, like, regardless of what you think about abortion, if people aren't able to get them, I'm anticipating a lot more patients showing up in the ER with, like, complications, or people who've attempted to do their own abortions and ...

LATIF: Ugh.

AVIR: ... hurt themselves in the process.

LULU: Yeah.

AVIR: So basically, you know, now at my job, you know, I have to occasionally organize conferences to teach ER residents things, and so I ended up hosting this OB doctor named Laura MacIsaac where I work, who for many years has been running the division in my hospital that deals with the abortions that we do. Now what I was anticipating was sort of like this high drama, ER-type of lecture of like, "All right, when a patient comes in with a coat hanger abortion, these are the things you gotta think about. It's gonna be sepsis. Here's how you evacuate." Or, you know, "Uncontrolled bleeding. Where are you—you know, what type of blood are you gonna do? How are you gonna match the blood?" This is what I was, in my mind, picturing the lecture would be about.

LULU: Mm-hmm.

AVIR: But it actually wasn't like that at all. What she sort of talked about ended up kind of blowing my mind in a completely different way.

LULU: Oh!

AVIR: So ...

AVIR: Hey!

LAURA MACISAAC: How's it going?

AVIR: I'm good. How are you?

MOLLY: Hello!

AVIR: I emailed Molly, and I was like ...

MOLLY: I'm Molly.

LAURA MACISAAC: Hi Molly. I'm Laura.

MOLLY: Hi. Good handshake!

AVIR: ... Let's just go talk to her.

LAURA MACISAAC: I'm so glad that it was more interesting than you expected. [laughs]

AVIR: And basically, she told us while we've all been arguing about the politics, the legality and the morality of abortion, the actual practice of it has been really on its own trajectory.

LAURA MACISAAC: Since I've been doing this work, it's changed probably more than any other thing I can think of.

AVIR: For the majority of abortions happening today, we're not talking about surgeries.

LAURA MACISAAC: No. It's with the medications to induce abortions. Pills.

AVIR: And while I knew that you can take pills to induce an abortion, I hadn't really thought about, like, how much this really does change everything about what it means to get an abortion, and how much of that has really just happened in the past few years since COVID. And in a weird way, because of COVID.

MOLLY: Okay, so the story starts back in the '80s. Roe v. Wade just happened, and you have greater access to abortions. And the way that we did abortions was surgically, right? So it was like the woman, you know, was put on a table, she's given anesthesia. Someone actually had to, like, go into a woman, into the cervix, and pull out the growing embryo or the growing fetus.

AVIR: And that's just sort of the way it was.

MOLLY: Yeah.

AVIR: Until two things start happening on opposite sides of the world.

LATIF: Hmm.

LULU: Hmm.

AVIR: The first one is in Brazil. So in Brazil, abortion was illegal. And Brazilian women, you know, when they would have an unwanted pregnancy, right, they would go into a pharmacy, and they saw on these ulcer drugs that there was like a little sign that says, like, "Don't take this in pregnancy."

LULU: Oh, interesting.

AVIR: So they started taking it.

LATIF: Hmm.

AVIR: And surprisingly, it worked. It would cause an abortion.

LULU: And how does that work? How does it do that?

AVIR: Well, so that drug, it's called Misoprostol. Misoprostol is a prostaglandin. And prostaglandin is something that we make in our body, and it does a bunch of different things all over the body. One of them is healing ulcers, but another one in the uterus, it causes it to basically contract.

LATIF: Hmm.

AVIR: That's it. And so if you're pregnant, you know, that can just basically make the uterus flush the embryo out.

LULU: Huh. So it just basically physically ejects it?

MOLLY: Mm-hmm. And so it induced abortions, but no one really knew, like, how much to take and stuff, and it was like ...

LATIF: Hmm.

MOLLY: ... "Do I take it in my mouth? Should I shove it up my vagina and, like, get it near my cervix or my uterus?" No one knows.

LATIF: Sure.

MOLLY: So really what they were seeing is that sometimes it didn't work.

AVIR: Right. So that's Misoprostol, which works some of the time.

MOLLY: Okay. Right. So meanwhile while all this is happening, in France, you have a doctor Étienne-Émile Baulieu. And his whole idea was, like, well in the early stages of pregnancy and throughout pregnancy, we really need progesterone.

AVIR: Right. Because progesterone helps the uterus build up a thick layer of, like, bloody tissue that can support a possible pregnancy. And the embryo, you know, needs to implant into that tissue.

MOLLY: And so he was like, "Well, if we know that a body has to amp up progesterone in order to facilitate a pregnancy, what if I did something that, like, interrupted that?"

LULU: Oh!

MOLLY: And so he and his research team develop this drug called RU-486, otherwise known as Mifepristone.

AVIR: So Mifepristone is basically a progesterone blocker. And so when you take Mifepristone, that layer can't grow. And essentially that signals the body to shed that layer. And essentially you're just saying—like, you just say "Nope."

LATIF: No place for you to implant here. Just move along!

AVIR: Yeah. So that's mifepristone.

MOLLY: There's one problem though, which is that mifepristone will cause the uterus to be an unfriendly place for the embryo, but it won't then actually expel that embryo.

LATIF: Hmm.

MOLLY: And so you need to combine something with mifepristone to make it flush out the uterus. So then the doctors in France are like, "Wait a second, we're hearing about this ulcer drug in Brazil that's kind of doing what we need, and so what if we take that and combine the two?" So then the misoprostol would get your uterus to, like, force out the stuff that has dropped off the edges of your uterus.

LATIF: Oh, wow.

LULU: Wow!

AVIR: Yup.

LATIF: Oh, that's very vivid and clear. Okay, yeah.

LULU: Yeah.

MOLLY: And then when they combine these two, what they see is like a 95 percent success rate, and it's very safe. Et voilà, they created the abortion pill. Okay, so in 2000, the Mife-Miso pill combo comes to the market in the United States.

LATIF: Oh, wow. So that's like—that's years later.

MOLLY: Yeah. So basically, like, there was, like, scientific testing we had to do in the States, but then there was also all this politics, because it is, like, an abortion drug.

LATIF: Mm-hmm.

MOLLY: But eventually they get approved, though even then there were still all these hoops that doctors were jumping through to get it to patients.

LULU: Hmm.

AVIR: Yeah.

LULU: Like what?

AVIR: Like, for example, doctors would run all of these tests.

LAURA MACISAAC: You had to check a blood count.

AVIR: This is Laura MacIsaac again.

LAURA MACISAAC: So you have to draw blood.

AVIR: To make sure—is this person anemic?

LAURA MACISAAC: We used to do a blood type.

AVIR: Check their liver function.

LAURA MACISAAC: Do an ultrasound and make sure that it was not an ectopic pregnancy.

AVIR: Every once in a while, a pregnancy will implant somewhere outside of the uterus. If it's in a fallopian tube that as it grows, it will rupture the mom's fallopian tubes.

LATIF: And these pills do work for that or don't work for that?

AVIR: No, it wouldn't work for that.

LATIF: It would not, yeah.

AVIR: No, because, you know, you are flushing out the uterus. But if the embryo is not in the uterus, it's just gonna keep growing.

LATIF: Right.

AVIR: And so that's like a super dangerous situation that, you know, that—this situation can happen in any pregnancy, but it can also happen, you know, in this type of scenario.

LATIF: Right.

AVIR: And I should say that, you know, you didn't have to do all these tests. Doctors sort of just did them out of precaution. But there were some things that doctors had to do. Like, the FDA rule was that they had to actually give the patient the pills in the office. Like, sit there and watch the patients take the pills.

LATIF: Like, literally watch them ingest the pills in their mouth?

AVIR: Yeah, exactly.

MOLLY: Is this all in one visit? Or are we at multiple visits at this point to get all of that done?

LAURA MACISAAC: Yeah. It—initially it could take two visits.

LATIF: Wait. So why all the regulations and the testing? Was it because of politics or because of science safety stuff?

MOLLY: Well, there was a little bit—some of it was politics, but then you also have to remember, like, the day before these pills came out, the abortion was a surgery.

LAURA MACISAAC: You know, we can't forget that reproductive events: abortion, miscarriage, childbirth can be fatal, right?

MOLLY: I mean, Laura was like, "Don't get me wrong. Most of the time these things go fine."

LAURA MACISAAC: Totally. But when it doesn't, it is scary, and you have to act fast. And the light bulbs have to go on and say, "Something's not right here. Why does she have a fever? She might be septic. I'm not gonna leave her side until I figure this out." So it's not like bad shit never happens.

MOLLY: And honestly, even when everything's going right, there's, like, you—you're heavy bleeding.

LATIF: Right.

MOLLY: There's uterine contractions. There could be vomiting, diarrhea. It's a full body experience that can feel and be scary, even if it ends up being okay. And for folks where it's not okay, like, they'd have to get themselves to a hospital or a doctor or even get a surgical abortion to, like, complete the procedure. So I did find myself when I was talking to Laura, like, saying, you know, as the person who could bleed from these pills ...

LATIF: Yeah.

MOLLY: ... like, I appreciate the guardrails. Because I have just a lot—I'm a person that has a lot of questions all the time. It's why I'm in the job that I'm in.

LULU: [laughs]

MOLLY: If I could just have a little doctor living in the corner of my house ...

LULU: [laughs] You would be so happy!

MOLLY: ... I would be the happiest person ever. 'Cause I ... [laughs]

AVIR: How little do they have to be?

MOLLY: Yeah. [laughs]

LULU: Just be like ...

LATIF: Avir's applying for the job, basically.

MOLLY: I know. I was like, there's an opening. So I would be the happiest person, you know? So I understand, like, knowledge satiation.

LULU: Yeah. Totally. Totally.

MOLLY: The one thing with all these guardrails, though, is that guardrails do make it hard to get these pills to patients, right? You're missing work for all of these visits. You know, all these tests are expensive.

LATIF: Mmm, yeah.

AVIR: Yeah. So to sort of like, advance the story, right? This is the state of play in 2000. And the Mife-Miso abortion is approved for up to seven weeks.

LULU: Okay.

AVIR: Now over time, like the next couple of decades, doctors are starting to—and these are OBs specifically, right? They're starting to experiment and test the boundaries of clinical practice. So ...

LULU: Someone tries an experiment, meaning a scientist?

AVIR: Yeah, like a researcher doing a clinical trial. So the initial dose of misoprostol was 600, I think, milligrams.

LULU: Yeah.

AVIR: They try—"Maybe we—this is pretty high. Let's try 400." Same efficacy. Then they cut it down to 200. Same efficacy. So the dose is going down. The weeks are going out because remember: at first, you could only give the pills up to seven weeks. And that's not that much time considering, you know, it's typically gonna be four weeks by the time you realize you missed a period. And then you have to get all your shit together, get these labs done, come back, get the ultrasound.

LATIF: Right.

AVIR: You know, it doesn't buy us that much time. So it started at seven, then they tried eight. Still works. Tried nine, still works. 10 still works.

LATIF: Whoa.

AVIR: Meanwhile the labs that are being drawn, doctors are starting to think, "Well, do we really need this lab? The type and screen where we check the mother's blood type, do we really we need that?" And they're experimenting with taking that out. Nothing bad is happening. The CBC, you're looking for anemia. Well, turns out, you can just ask someone if they have anemia. They take the CBC out.

MOLLY: And I just want to say, a lot of this experimentation started in other countries. So it'd be like, "Oh, the UK is doing it this way now. That's interesting." And then, you know, Sweden would do something. And then France would try something.

AVIR: Right.

MOLLY: So basically what you see with these pills is just this kind of steady—steady step of progress in the science around them and the ways that we give them to people.

AVIR: And then COVID happened. And almost overnight everything about the way we use these pills changes in a huge way. So now it's the beginning of 2020, and these pills are around, they're becoming more and more common.

MOLLY: Yeah, so 54 percent of abortions in the United States are happening because of these pills.

AVIR: And then COVID happens. Everything changes. Women still need to have abortions. And the ACLU ...

LATIF: Right.

AVIR: ... leads a lawsuit against the FDA basically saying that forcing patients to come into the office to get these pills poses a huge medical risk to both the doctor and the patient.

LATIF: Now. Because of COVID?

MOLLY: Because of COVID.

AVIR: Right? And they win. So now patients don't have to come into the office to get these pills.

MOLLY: Yeah. And on top of that, doctors did away with ultrasounds and testing for all but the most high-risk patients.

AVIR: So now all of a sudden, the majority of abortions are happening over video chat. They're essentially becoming, like, quote, "no touch."

LAURA MACISAAC: No touch abortions.

AVIR: That's Laura MacIsaac again.

LULU: Was that like—for people who are doing this, was that a huge moment?

AVIR: Huge. When telehealth abortions first started ...

LAURA MACISAAC: I remember my first feeling was, "Oh, some bad things are gonna happen. We're gonna miss some ectopic pregnancies, or patients are gonna estimate their gestational age poorly." I'm just used to doing it with the patient in front of me.

AVIR: In medicine, you know, it's like we're super conservative. We don't want to rock the boat. We—one mistake makes us all feel terrible.

LULU: Yeah.

AVIR: Even if 99 of the rest of the time it went fine. But it turns out ...

LAURA MACISAAC: Telehealth abortion and in-person abortion have the same outcomes.

AVIR: There's absolutely no difference.

LULU: Oh my gosh! Really? Nothing? Nothing?

AVIR: Nothing. So the efficacy rate is the same, right? The failure rate is the same. The adverse event rate is the same.

LULU: That's wild. So it's like the worries may have been legit, but the worries were in vain.

AVIR: Yes. Yes.

LULU: Wow.

LATIF: I'm kind of shocked. Like, I feel like, especially when COVID first hit, like, there were all these stories of like—like, it's like people doing Zoom funerals and Zoom weddings, and those are all—and then but, like, nobody was talking about Zoom abortions going on at the same time.

AVIR: Yeah, exactly. And I mean, Laura's take on it is that, like, all of this happened precisely because, you know, there was so much else going on, and neither the pro-abortion movement or the anti-abortion movement even got the chance.

LAURA MACISAAC: They were too distracted by COVID to be fighting these ...

AVIR: Fighting over how doctors should be doing these abortions.

LATIF: Huh. Wow!

AVIR: Yeah. But there's actually one more thing that Laura told us.

LAURA MACISAAC: ... zoning in on the US ...

AVIR: Something that almost feels like a signal of what abortions might look like in the future.

LAURA MACISAAC: So this nonprofit called Aid Access has been providing women with Mifepristone and Misoprostol through the mail. And ...

MOLLY: Aid Access is the US branch of this abortion provider that is literally mailing abortion pills all around the world.

LULU: Huh!

MOLLY: And it's run by this European doctor who has developed a company to practice essentially in other countries where access to abortion is really limited. What you do is you go online, you fill out a questionnaire, and then a doctor on the other end would read it, and if they felt like you qualified to have a medical abortion, they would mail you the pills directly to your house.

ABIGAIL AIKEN: In the first two years of the service, there were 57,506 requests from people in the United States, and they came from all 50 states.

AVIR: This is Abigail Aiken, professor at the University of Texas-Austin.

MOLLY: Abigail and her team looked at data from almost 3,000 of those patients, and ...

ABIGAIL AIKEN: We found that 96 percent of people were able to end their pregnancy without any intervention from a medical provider.

MOLLY: How does that compare to the same statistics for if this is done in a clinic setting?

ABIGAIL AIKEN: Yeah, that's a great question. So these results in terms of effectiveness are really on par with what you would see in the clinical setting.

MOLLY: Really?

ABIGAIL AIKEN: Yeah.

MOLLY: Again, same results. No greater adverse events, even when a doctor and a patient weren't speaking to each other at all.

AVIR: Yeah.

MOLLY: On top of that, they also looked at how far into pregnancy people were actually using these pills and the results with that. So, like, here in the US, they're approved for only up to 10 weeks.

ABIGAIL AIKEN: Yeah, you know, we decided to break that down as you saw. We chose 10 weeks because that's the situation here in the US, right? That's what the FDA says. But there's an argument to be made that the FDA is kind of actually a bit out of date with that evidence. WHO, for example, says 12, 13 weeks because they have more recently reviewed studies that have actually looked at medication abortions being done in that kind of end of the first trimester period. Admittedly, it's a small number of people who were over that 10-week mark, but we thought let's see if there's a decline. And we did see a little decline in effectiveness. We expected that. What we do know is that further along you are in a pregnancy, the more likely it is that you will need more Misoprostol or a procedure from a provider to help you to end the pregnancy. That's not to say you fall off a cliff and suddenly the pills are ineffective. It's to do with how much, you know, extra risk a person is willing to accept to do the abortion the way they want to do it. You know, with Aid Access, the reason that people were over the 10 weeks was usually due to a shipping delay. So international shipping, we're talking about sometimes the pills could be at your door within five days, sometimes it could be two weeks. And people were experiencing a variety of times, and especially if that was taking a couple of weeks, you know, trying to like—it's out of Aid Access's control, it's international shipping. But they sort of worry that are these gonna come? Am I gonna run out of time? What's gonna happen to me? And so for some people that did push them beyond the 10-week mark.

MOLLY: And can I just say also that there was this other result that was very interesting ...

ABIGAIL AIKEN: There were actually several ectopics—not many, a handful. Maybe five in one study, three in the other, that were diagnosed by the service at the time of consultation. So the person would share symptoms of some kind and they would say "We think that's probably an ectopic. You should go get that checked out before you proceed with this." And they would actually get into care earlier than if they had waited until they had, you know, severe abdominal pain and vomiting.

AVIR: So you mean it's like the form that they did sort of flagged them?

ABIGAIL AIKEN: Yeah, exactly.

LATIF: Wow.

AVIR: Yeah. So it's a—it's a crazy study. This is the idea that had been percolating, and Aid Access is definitely the vanguard, but it's this idea of the self-managed abortion. And I think of it like—Molly's probably tired of me hearing—saying this same metaphor.

MOLLY: Never. Never!

AVIR: [laughs] But Jenga. I just played it the other day.

LULU: Okay.

AVIR: I see this whole thing like a game of Jenga, right?

LATIF: Mm-hmm.

LULU: How?

AVIR: When—when the medicines come out, we have a perfect block of Jenga. You know, like the whole structure's there. And as physicians, we're very scared to take things out of this structure, but we start saying, "Well, you know, really, I don't know if we need this particular lab. Hepatic function? Whatever. Let's take that out." The structure still stands, you know? Boom, boom. We keep taking out different parts of this Jenga tower. With COVID, huge chunks of the Jenga tower come out, the structure's still standing. And so what's incredible is just the amount of pieces we've been able to take out of this Jenga tower and have it still stand. And really, what's the last piece that is always there is the doctor.

LATIF: Hmm.

AVIR: You know? We put ourselves at the center of this whole process. Partially out of care, but partially probably out of some hubris, I would say, you know?

LATIF: [laughs]

AVIR: And so taken to its fullest, the self-managed abortion is really saying: what if there's no face-to-face contact with a doctor at all? What if you fill out a form, and if you check the right boxes on this form, then you're just good to go? You do this completely on your own. And so that idea, I think, is subtle, but from my perspective it's profound. There is no doctor directly involved in your care. You know, it's like getting a—like, an Ikea couch, you know? It's just like "Here's the instructions."

LATIF: Hmm.

AVIR: So—so, like, what does this mean? You know, that's what—that's what I keep asking myself is like, so what? And so right now 90 percent of abortions are happening in the first trimester where you could potentially use these pills. And so the "so what" to me is that, like, what these pills are telling us is that we now have the ability to take abortions—a good chunk of them—outside of clinics, outside of hospitals, outside of institutions, and put them into the hands of people. Which I think is just such a cool and interesting trajectory. That said, you know, one thing I think important to note is that we're talking about abortions with pills, but there are a chunk of people for whom that doesn't apply at all, you know? They need to get the old-school, you know, surgical abortion. And that's fine. But the percentage of people getting an abortion using pills, it's literally just a line graph that just keeps going up every year. And it's really just happening because of the science of these pills.

LATIF: Can I just say it's, like, so funny to hear you both tell this story. Because it's like, we're so used to every story about abortion, it's all about the politics. It's, like, so politically drenched, it's like every single little detail about it is like—is like a culture war. But what you're telling is like the story that seems like there's no politics in it, really.

AVIR: Right.

LATIF: Or very little. Which is kind of surprising to me. It's like, making me do a double take, kind of.

AVIR: That's what I think is so incredible is like science moves based on science, more or less. I mean, you know, obviously there's politics involved, but in this case, I'm seeing that these pills keep moving and moving and moving in the same direction. It's bigger than politics, it's bigger than the Supreme Court, it's bigger than all of that.

LULU: Contributing editor Avir Mitra and senior correspondent Molly Webster.

MOLLY: If you, like us, can't get enough on this topic, go to the New Yorker Radio Hour. They just put out this episode called "The New Abortion Underground" about something called "Pill fairies," which are folks who are bringing the abortion pills across the Mexico border into the US. It's a great story. It's well done. Go check it out.

[LISTENER: Radiolab was created by Jad Abumrad, and is edited by Soren Wheeler. Lulu Miller and Latif Nasser are our co-hosts. Suzie Lechtenberg is our executive producer. Dylan Keefe is our director of sound design. Our staff includes: Simon Adler, Jeremy Bloom, Becca Bressler, Rachael Cusick, Ekedi Fausther-Keeys, W. Harry Fortuna, David Gebel, Maria Paz Gutiérrez, Sindhu Gnanasambandan, Matt Kielty, Annie McEwen, Alex Neason, Sarah Qari, Anna Rascouët-Paz, Sarah Sandbach, Arianne Wack, Pat Walters and Molly Webster. With help from Andrew Viñales. Our fact-checkers are Diane Kelly, Emily Krieger and Natalie Middleton.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.