Oct 22, 2013

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey, everybody, real quick. So this coming up is a rebroadcast, but if you stick around all the way through, after the third segment we have an update on the HeLa story, one of our favorite stories, that is pretty freakin' fascinating. So definitely stick around for that.

[RADIOLAB INTRO]

ROBERT KRULWICH: Hey.

ADRIANNE NOE: Hi.

ROBERT: How are you?

ADRIANNE NOE: I'm fine. How are you, Robert?

ROBERT: Nice to speak to you after all these years.

ADRIANNE NOE: Yes. It's been quite a few years.

ROBERT: I should let you know that Jad Abumrad has just wandered in.

JAD: Hello?

ADRIANNE NOE: Hi.

ROBERT: And Jad, this is Adrianne Noe.

ADRIANNE NOE: Last name is N O E, and I'm director of the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

ROBERT: So, you know why we're calling you, right?

ADRIANNE NOE: Yes.

ROBERT: Okay. So let's just spring it on the audience.

JAD: [laughs]

ROBERT: I don't remember how I happened to bump into you. I don't even know how this came up.

ADRIANNE NOE: I think you and I had been co-presenters at a TED conference.

ROBERT: Well, maybe that's what it was.

ADRIANNE NOE: Probably a decade ago. I—we may have been talking about important events in New York or civic architecture, but I—but I do remember perking up at the phrase "Grant's Tomb."

JAD: Grant's tomb? So Robert said something to you about Grant's tomb.

ADRIANNE NOE: Yes.

ROBERT: And then you turned to me and—say it again.

ADRIANNE NOE: Well, you may know who's buried in Grant's Tomb, but I know what's buried in Grant's tumor.

JAD: Tumor? Christ.

ROBERT: [laughs]

ADRIANNE NOE: Yeah..

ROBERT: You'll see it turns out that at the museum she works at, there is...

ADRIANNE NOE: A tumor that had been excised from the throat of President Grant in the 1880s.

JAD: Actual tissue from Grant's tumor?

ADRIANNE NOE: Yes, that's right.

JAD: Oops. Yes. Here we are.

ROBERT: We're outside the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

JAD: Hey, wait for me.

ADRIANNE NOE: It is kept behind several locked doors.

BRIAN SPATOLA: So you guys don't have an inkling of what you're about to see if we go in there?

JAD: No.

BRIAN SPATOLA: But it's a, you know, privileged area.

JAD: This is Brian Spatola, he's the collections manager and he let us down a long hallway.

ROBERT: Through some doors into a back room.

ROBERT: Oh!

JAD: Holy, holy. So, oh my God. There's like a, they're twin babies in, in formaldehyde.

ROBERT: Look! Brains. Heads. Torsos.

BRIAN SPATOLA: And majority...

ROBERT: We haven't even gotten to the tumors.

BRIAN SPATOLA: Right.

JAD: So he led us out of that room and into another one.

ROBERT: And there, sitting on a table and waiting for us...

JAD: Is this—is this the thing about which we spoke?

BRIAN SPATOLA: It is.

JAD: Was President Ulysses Simpson Grant's tumor.

ROBERT: Oh, wow.

JAD: Lovely.

ROBERT: It was resting in a box that looked, as it happens, exactly like a..

ADRIANNE NOE: Cigar box.

ROBERT: Uh oh! [laughs]

JAD: Ooh!

JAD: Which is a little ironic.

ROBERT: This was the guy who never, ever stopped having a cigar in his house.

ADRIANNE NOE: He never stopped having cigars. He smoked as many as 12 cigars a day.

JAD: Wow.

ROBERT: So it was probably the cigars that made the tumor.

ADRIANNE NOE: February of 1885. Tissue was removed, examined and his physicians concluded that he had a squamous cell carcinoma. And ultimately he was treated for pain and died in July of 1885, that same year.

JAD: Oh wow. It's pretty fast.

ADRIANNE NOE: Mm-hmm. .

ROBERT: So that's what killed President Grant then?

ADRIANNE NOE: Was a tumor. Yes.

ROBERT: I didn't know that.

BRIAN SPATOLA: So, you see the staining that they used to bring out the details in the cells?

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: Is the darkness the tumor?

BRIAN SPATOLA: The darkness is the tumor.

ROBERT: Wow.

ROBERT: The very stuff that, even though President Grant got through Vicksburg, and even though he came east and they—they tried to kill him here. They tried to kill him there. They tried to—then he goes and becomes president. This is what actually killed him.

ADRIANNE NOE: This is what killed him.

JAD: Wow.

ROBERT: Can I touch it?

BRIAN SPATOLA: Um, no.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: [laughs]

ROBERT: We may not be able to touch the actual tumor of the President of the United States, but we can touch on this subject.

JAD: [laughs]

ROBERT: We can grasp this subject. We can examine this subject. Coming up on Radiolab for the next hour. It's totally tumors.

JAD: Oh, come on. Don't call that. Because really what we're gonna talk about are not just any tumors but famous tumors.

ROBERT: Immortal tumors!

JAD: Devil tumors.

ROBERT: Contagious tumors.

JAD: And tumors that speak ...

ROBERT: [whispering] In the voice of God.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich, not to be confused ... [laughs]

JAD: [laughs]

ROBERT: ... with the big one.

JAD: And I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: And this is Radiolab.

JAD: Stay with us. All right. To get things—to get things rolling. This first story is about something that we thought was not possible. That we hoped was not possible.

ROBERT: We learned it, no problem. From...

DAVID QUAMMEN: I'll make it work.

JAD: From this guy.

DAVID QUAMMEN: David Quammen. I'm a science journalist.

ROBERT: He's, I think, my favorite in my generation. I think he is the best writer that writes about science.

DAVID QUAMMEN: I specialize in evolutionary biology and travel on assignment to far away places and interesting situations.

ROBERT: All right, so first of all, where are you going to take us? To what part of the world?

DAVID QUAMMEN: I'm gonna take you to Tasmania, which is the island state off the south coast of Australia. You know, you go to Australia and you think of rock and deserts and red dirt and heat, but you keep going south, all the way off the south coast. Suddenly you have these rolling green countrysides. Lots of wallabies, one of a species of kangaroo that are abundant...

ROBERT: Like England countryside with wallabies? Is that the...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Exactly. With small kangaroos hopping around.

ROBERT: [laughs]

ROBERT: Yeah.

ROBERT: But our story does not actually begin in Tasmania.

JAD: Nope. It starts in Holland.

ROBERT: With the gentleman by the name of...

CHRISTO BAARS: Christo Baars.

JAD: Is that "Baars" as in B A A R..

CHRISTO BAARS: [pronounced] "Barsh." Yes.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Christo Baars is a wonderfully independent spirited plumber.

JAD: A plumber?

CHRISTO BAARS: Yes.

ROBERT: Huh.

CHRISTO BAARS: Plumbing I do to make a living, and photographing is for me a big hobby.

ROBERT: We don't know just how great a plumber he is, but he's a very good wildlife photographer and he looks for interesting animals to shoot—with the camera, I mean. So over the years, very often he puts down his range and he travels.

CHRISTO BAARS: Yeah. Well, we don't have that many animals here in Holland. Little bit of road deer and sometimes a fox.

ROBERT: And in the early nineties...

DAVID QUAMMEN: He goes to take his latest photography sabbatical in Tasmania.

CHRISTO BAARS: I went to Tasmania on—on boat.

JAD: And were you there to take pictures of wallabies or kangaroos?

CHRISTO BAARS: No, no, no, no.

DAVID QUAMMEN: He was there this time to photograph ...

CHRISTO BAARS: Devils.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Tasmanian devils.

CHRISTO BAARS: Yeah. I—I quite like the animals.

JAD: What does—I mean, I know the cartoon, but what does a real Tasmanian devil actually look like?

CHRISTO BAARS: Well, they're about as big as a little pitbull.

DAVID QUAMMEN: But look a little bit more like a bear cub.

JAD: Huh?

DAVID QUAMMEN: White yoke on its chest. Big set of formidable teeth. They'll eat almost anything.

CHRISTO BAARS: Anything. Anything they can find. Platypus ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Kelp, maggots and ...

CHRISTO BAARS: Fish.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Snakes.

CHRISTO BAARS: Garbage cans.

CHRISTO BAARS: The occasional rubber boot...

ROBERT: [laughs]

CHRISTO BAARS: You name it.

ROBERT: Anyway, when Christo gets to Tasmania, he drives up the coast. He finds dead animals on the road, you know, roadkill.

CHRISTO BAARS: Roadkill from the road...

ROBERT: To use as bait.

JAD: What sort of roadkill?

CHRISTO BAARS: Well, kangaroo.

JAD: A little devil can eat a kangaroo?

CHRISTO BAARS: Oh yeah. When there are three, four, or five together, they eat a big kangaroo. In an hour it's gone.

JAD: Wow.

ROBERT: So he takes the dead kangaroo, drags it to a clearing in the forest. Sets up his photography equipment, very close.

ROBERT: And then what happens?

CHRISTO BAARS: Well, you just wait.

ROBERT: So he waits. And as the night falls, little black shapes begin to creep out of the woods.

CHRISTO BAARS: You can hear them sniffing. And they—they'll find a road kill

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Tasmanian devil, sounds like ripping into something]

CHRISTO BAARS: Then they just start eating and fighting with each other. This is quite scary if you don't know what, what you're hearing

ROBERT: As they eat, Christo, standing at a safe distance in the shadows, takes their pictures. Over the years, he's done this over and over and over and he always sees lots of Devils.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Devils in front of his lenses.

CHRISTO BAARS: Sometimes 20 devils running around.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Devils in his kitchen...

CHRISTO BAARS: Are coming to your tent.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Devils everywhere.

ROBERT: But after a bunch of trips, something happened. It was Easter 1996, he was in the park watching a dead kangaroo and waiting for the devils to show.

CHRISTO BAARS: But only thing I saw was one devil.

JAD: Just one?

CHRISTO BAARS: Yeah. So I thought, "Eh, I'll try another spot." And another spot, tried it out. Two devils.

DAVID QUAMMEN: They're not gone entirely, but they're scarce. And he notices something strange about one or two of the devils. There was something on the faces.

CHRISTO BAARS: The face, and on the back, and, on their mouth.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And something that looked like a growth. A large ugly growth.

CHRISTO BAARS: So I thought, "Well, maybe they've been bitten or fighting with each other. A bit swollen up." But it was really big, you know? And blood coming out and ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: This was the first alarm bell.

JAD: So Christo, you were the first to see it?

CHRISTO BAARS: Yes. Yeah.

ROBERT: And this was just the beginning.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Like a plague out of hell. A dark death is sweeping Tasmania…]

ROBERT: Television reporters got the story.

[ARCHIVE NEWS CLIP: They never confronted anything like this.]

ROBERT: And began reporting that more and more Tasmanian devils had these lumps on their faces.

DAVID QUAMMEN: They fill the eye sockets. They puff out the lips. They infect the gums. It's really sad and hideous.

ROBERT: And whatever they were, they turned out to be lethal.

DAVID QUAMMEN: To jump ahead a little bit, the effect that it's had in the population ...

ROBERT: In some cases, devil populations collapsed by 90 percent.

DAVID QUAMMEN: ... died off.

ROBERT: Very quickly, scientists looked at the disease and determined that it was some kind of...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Tumor.

ROBERT: Cancer.

DAVID QUAMMEN: A cancerous tumor.

ROBERT: And then the question was, what's causing them?

JAD: So what—what—what did they think?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Well, a toxic chemical was, guess number one.

ROBERT: Some poison or pesticide from the environment.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Guess number two was a virus.

ROBERT: So they tested in places where the devils live, looking for something toxic or some virus, and they found nothing.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And then, along comes a woman named Annemarie Pierce. She looked at some tumors close up, very close up, from 11 different devils.

ROBERT: So she's looking at the first tumor.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And she found that the chromosomes were sort of mangled.

JAD: Which isn't really that strange 'cause that's what cancer is. It's like your genetic stuff gone screwy.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Right.

ROBERT: But then, she looked at the tumor from the next devil.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And she found not just also mangled chromosomes, but chromosomes that were mangled in exactly the same way as they had been in the first devils.

JAD: Hmm.

ROBERT: So now she looks at a third ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Identical.

ROBERT: And then a fourth ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Identical.

ROBERT: And then a fifth.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Identical.

ROBERT: All 11 ...

DAVID QUAMMEN: Exactly the same pattern in each.

ROBERT: [menacing] Tan tan tan tan!

JAD: Does that—I—I feel the sensation of awe, but I don't quite have the understanding attached . Does that mean that—that these tumors are all brothers?

DAVID QUAMMEN: What that meant was that these tumors were all genetically identical.

JAD: What?

DAVID QUAMMEN: They were all the same tumor.

JAD: How can they all be the same tumor?

ROBERT: Well, they can't because—because that would mean that these Tasmanian devils caught the cancer from some other Tasmanian devil.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Exactly.

JAD: Wait, what do you mean exactly? You can't catch cancer.

DAVID QUAMMEN: This epidemic of cancer in Tasmanian Devils was a crazy impossible tumor that was jumping. It was leaping from one devil to another.

JAD: A leaping tumor.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Yeah, a leaping tumor.

JAD: And this is the point in this tale where we really have to question everything that we thought we knew about cancer. Now most people think of cancer as, like a..

DAVID QUAMMEN: The situation in which one of your cells starts replicating and doesn't stop. It replicates uncontrollably until it destroys you.

JAD: Okay. So that's like the one cell theory, which is frankly how I thought cancer worked.

CARLO MALEY: Oh, Peter, we have to go ahead to start.

JAD: But then we spoke with this fellow.

CARLO MALEY: Yep.

JAD: His name is Carlo Maley.

CARLO MALEY: Cancer biologist at the Wistar Institute.

JAD: He told us, if you really wanna understand what's happening with the devils, you gotta toss out the one cell theory. Because cancer is not just..

CARLO MALEY: It's not just a cell going, "Hey Laura."

JAD: No. It's actually many cells competing ...

CARLO MALEY: Competing for space, competing for resources.

JAD: And in the process driving each other haywire. Like if you were to somehow go into a tumor, he says, what you would find..

CARLO MALEY: Is between a billion and a trillion cells in there.

JAD: These are different cells, this huge clump of cells. And they're—they're all fighting it out. 'cause you know, space is tight, food is scarce, and what'll happen is in the middle of this melée, you know, as the cells are competing, each individual cell is trying to copy itself. Copy, copy, copy. And somewhere along the way you get, eventually, a copying error. And every so often says Carlo, one of these mistakes will give the new cell a new talent. And in the case of cancer, it usually starts with something pretty simple like the ability to slurp up food faster.

CARLO MALEY: Nutrients like oxygen and glucose.

JAD: And now, with this advantage ...

CARLO MALEY: That mutant and all of its progeny will take over that area of the tissue.

JAD: But... not for long because now you got all these mutants and they start to fight. Until randomly again, you get another copying mistake. And maybe this second copying mistake gives the cell the ability to divide faster, right? So there it is.

CARLO MALEY: Proliferating faster than its neighbors.

JAD: And it takes over.

CARLO MALEY: Growing and displacing the other cells.

JAD: But yeah, it just keeps getting worse 'cause now you've got these double mutants. They can eat fast, they can divide quickly, and they start to fight until you get a third mutation, then a fourth.

CARLO MALEY: And you just keep ratcheting it up. And eventually, roughly five to 20 mutations ...

JAD: You end up with a cell that is so gnarled, so mutated, and so powerful that it can literally spit a kind of acid.

CARLO MALEY: Called a matrix metalloproteinase that allows it to rip through the membrane barriers.

JAD: And this is when you're really in trouble, 'cause now the cell can roam.

CARLO MALEY: And so the cells leave the—the primary tumor. They've gotta dissolve their way into a blood vessel.

JAD: That's a mutation.

CARLO MALEY: Then they've gotta survive in the blood.

JAD: Another mutation.

CARLO MALEY: Then they've gotta stick somewhere else.

JAD: Yet another.

CARLO MALEY: Then they've got to dissolve back through the archaeal lining.

JAD: And another.

CARLO MALEY: Yeah.

JAD: So it sounds like cancer is always evolving to be more cancerous.

CARLO MALEY: It totally is. This also explains why we haven't been able to cure it.

JAD: Why, when a person takes chemotherapy drugs, the cancer will go away for a while, but then it'll come back stronger 'cause the cells have evolved a resistance to those drugs.

CARLO MALEY: When I first got into work on cancer, I was impressed at how malevolent the disease seems as if it's being designed to kill us.

JAD: So here's my question. This leaping tumor in the devils...

CARLO MALEY: Mm-hmm.

JAD: Is this a case where the tumor is actually evolving into a new form, like after, say the 50th mutation or whatever? Like now it—it doesn't just have the ability to travel in a body, but it can somehow leap out of a body through the air and into another body?

CARLO MALEY: Sure. I mean...

JAD: But I mean, that's really scary.

CARLO MALEY: Yes, it is—it is pretty scary. But—but this is amazingly rare.

JAD: And according to Carlo demands some pretty special circumstances.

ROBERT: How would, in a Tasmanian devil, would some tumor get from one individual to another? What would—what—How would that happen?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Tasmanian devils, God bless them, bite one another in the face a lot. They're scrambling over carcasses. They're—they're fighting and, and biting and swallowing and crunching. And the males also bite females during the mating period. He's a little bit of a rough lover. So you have the male and the female biting each other in the face.

JAD: So a devil with a tumor on its face, let's say it's mating with another devil, and it bites that second devil in the face. What exactly happens at that point? Is it just rubbing it's tumor against ...?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Okay. When—when you think of these big ugly tumors, think of feta cheese.

JAD: [with disgust] Ooh...

DAVID QUAMMEN: And when one devil bites another, there's a tendency for the tumor to crumble ...

JAD: [with disgust] Ugh!

DAVID QUAMMEN: ... and to shed tumor cells that then fall into the wounds on the second devil.

ROBERT: But something here, I don't understand. Why wouldn't the immune system of the devils..

DAVID QUAMMEN: Kill those cells? Prevent those cells from taking root?

JAD: Yeah. 'cause that's what immune systems do.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And the latest answer is that, well, Tasmanian devils don't have as much genetic diversity as you would expect.

ROBERT: What that means, David explained to us, is that the Tasmanian devil population has gotten so inbred, they're so alike at a genetic level, that their immune systems are now confused. They don't know the difference between their own cells and invading cells coming in from other devils.

DAVID QUAMMEN: Exactly.

JAD: Which doesn't actually sound like the tumor is all that powerful. So I asked Carlo Maley ...

CARLO MALEY: Well, you get a mutation that ...

JAD: ...is this really the story of a tumor evolving?

CARLO MALEY: .... is more adaptive.

JAD: Or is it just the story of a tumor getting lucky?

CARLO MALEY: Those, I think those are the same story.

JAD: How do you mean?

CARLO MALEY: I mean, evolution is all about dumb luck.

JAD: The way he explained it, it's dumb luck that the tumor was on the outside of the face. It's dumb luck that they bite each other a lot. That a cell could come along that could shed and fall into a wound. It's all dumb luck. But that he says is what makes evolution happen.

CARLO MALEY: That's natural selection right there.

ROBERT: And when you step back, sometimes the results are just...

JAD: ...nuts!

ROBERT: Yeah!

JAD: Just nuts.

DAVID QUAMMEN: And this is the point where we need to talk about a transmissible tumor in—in dogs. Canine transmissible venereal tumor.

JAD: This is a tumor, he says, that's evolved way beyond the one in the devils and way longer.

ROBERT: How long has that been going on?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Well, it's been going on for somewhere between 200 and 2,500 years.

ROBERT: Whoa, whoa.

JAD: Whoa. Between 200 and 2,500 years?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Yeah. Yes, yes.

JAD: Over two millennia?

DAVID QUAMMEN: Exactly. And if that's the case, then it's the oldest continuous animal cell line in existence on planet Earth.

JAD: You might need to say that again.

ROBERT: [laughs]

DAVID QUAMMEN: [laughs] Okay.

JAD: Because that is just too strange.

DAVID QUAMMEN: It is. It is.

JAD: Even stranger, says David Quammen, when a tumor lives this long, propagates itself this long, you can only really call it one thing.

DAVID QUAMMEN: This tumor is essentially an animal. A parasite. Not a species of parasite, but one individual parasite.

JAD: That may never die.

ROBERT: David Quammen is the author of "Song of the Dodo" and "Natural Acts."

[DAVID QUAMMEN: This is David Quammen calling from tropical Bozeman. Radiolab is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

[LISTENER: And the National Science Foundation. Radiolab is produced.]

LISTENER: By WNYC and distributed by NPR.

ANSWERING MACHINE: End this message.]

JAD: Hey, this is Radiolab. I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich. The topic is totally tumor, of course.

JAD: That's my line, by the way.

ROBERT: Oh!

JAD: No, no. So yeah, we've been talking about tumors this hour, famous tumors, and thus far they've been really bad.

ROBERT: Terrible tumors.

JAD: Really bad.

ROBERT: Scary, horrible tumors.

JAD: But!

ROBERT: Because we are fair minded about everything.

JAD: Even tumors.

ROBERT: Let us consider the possibility that sometimes tumors can be rich, beautiful, and desirable.

JAD: For example,

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer: George Malley is an ordinary man who is about to become extraordinary.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer: Name as many mammals as you can in 60 seconds.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer: How about alphabetical? Aroc, bat moon, caribou dolphin, [unclear]. Are you getting this? What is going on, George? ]

JAD: In this 1996 movie, John Travolta plays a guy who gets a brain tumor. And the tumor...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer: Oscar-worthy performance…]

JAD: ...makes him into a genius.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer: John Travolta, in Portuguese]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer: You learn the Portuguese language in 20 minutes?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer, John Travolta: Not all of it!]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Phenomenon trailer: Phenomenon!]

ROBERT: He didn't learn the accent though. [laughs]

JAD: [laughs] The tumor doesn't give accents.

ROBERT: But it—But it does—it does raise a real question, which is like, can it—is it possible for a tumor to create...

JAD: Something good?

ROBERT: Yeah.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: Hello Jad. Nice to meet you.

JAD: Nice to meet you.

JAD: So we paid a visit to a guy, a doctor named Orrin Devinsky.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: I'm a neurologist at NYU Langone School of Medicine.

ROBERT: And Dr. Devinsky has had a lifelong interest in the beneficial effects of certain kinds of brain conditions.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: Right. I'll just tell you, I think one of the most fascinating cases in neurology very quickly ...

JAD: And this one we were not prepared for.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: A gentleman was described, who ever since he was a child, would look at safety pins and have an orgasm.

ROBERT: At safety pins.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: At safety pins. The more shiny and the more numerous the safety pin, the stronger the sexual experience.

ROBERT: And this happened from his pubescent period. He just—safety pins turned him on?

ORRIN DEVINKSY: Sometime at puberty, he made this association. When he looked at a safety pin, he had an orgasm. So ...

ROBERT: He got to have been embarrassed by this. This is worse than being ...

ORRIN DEVINKSY: So, yeah. So he would go into private—He realized this is not something most people do. He never talked about it. And he did it in private. And then he got married. After the war, he was honorably discharged and got married and then started having less sex with his wife because the safety pin was much—safety pins were much more enjoyable. Sometimes he just had to think about his safety pin, not even hold it up.

ROBERT: So we—are we seriously making the case that this guy is getting a benefit from his...

JAD: Not seriously.

ROBERT: ...pin obsession?

JAD: But I think actually you could say that the experiences that this guy was having with those safety pins gave him a kind of pleasure that maybe is unavailable to the rest of us.

ROBERT: From an odd, odd source. But you know, pleasure’s pleasure.

JAD: Until, says Devinsky, this fellow began to have seizures.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: Got admitted to a psychiatric hospital in London, the Maudsley, one of the big psychiatric units. They actually got an EEG, and to make a long story short, there was a benign tumor.

ROBERT: Right in the part that's called the temporal lobe, sort of in the middle of your head, right behind your eyes.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: But they took it out.

ROBERT: They took it out.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: They took it out. And they cured him of his wonderful experience. So he—he never was able to—He could look at safety pins all day long, but he would never again, enjoy them the way he had for his whole life.

JAD: How did he feel about that?

ORRIN DEVINKSY: I think it was a mixed blessing, as you would imagine.

MARK SALZMAN: Well, I've got blue jeans on and sneakers...

ROBERT: And this idea that from a tumor you can get something not so good, but also something good. This is an idea that has—Well, there's been a—a novel written on this theme.

MARK SALZMAN: The title of the book is Lying Awake.

ROBERT: By a friend of mine.

MARK SALZMAN: My name is Mark Salzman.

ROBERT: Mark is a writer who lives out in California and he thought, I'm gonna imagine a nun.

MARK SALZMAN: Our main character is Sister John of the Cross.

ROBERT: This is a woman who had joined a nunnery because she felt just lonely for a relationship with God.

MARK SALZMAN: Yes. It's just not enough for her to tell herself, "yes, God is there." What she longs for is a tangible sense of God's presence. A—a—a sense that she can really feel God's presence in her life. And, She—she begins having what she thinks are migraine headaches. The—the regular doctor that the sisters see tells her that she seems to be having migraine headaches. They're coming more and more frequently. And there comes a point when one of these headaches changes dramatically, and then everything is different.

ROBERT: Everything is different. What's different? Well, what happens?

MARK SALZMAN: Shall I read?

ROBERT: Yeah, go ahead.

MARK SALZMAN: You—you kind of have to imagine this scene taking place in an environment of profound silence. She's in the cloister. She and one other sister, they're working on a sewing project. They're sewing an altar cloth. "One of the pins slipped out of her hand, ringing like a miniature triangle as it bounced off the floor. She looked down to the floor and saw that it looked impossibly distant. When she reached down for the pin, her hand looked strangest of all. As if it belonged to someone else. The silence in the room came alive, like the words left out of a poem. Something buried so deep inside her that she'd forgotten. It was there rose to the surface. 'Sister, are you not feeling well?' God was present in Sister Ann's voice. He was present in her face. Nothing was changed yet everything was changed. 'God is here,' she answered. 'You are here all along.'

ROBERT: Well, this is a field goal, isn't it? For someone who is seeking a spiritual connection. She has one.

MARK SALZMAN: That's right. She—this is the moment she's been waiting for all her life.

ROBERT: But there is a problem because when these feelings come...

JAD: I'm sorry. She has a tumor. Let's just get the non surprise out of the way.

ROBERT: The show is called "Totally Tumor!"

JAD: Alright! I'm just saying!

ROBERT: She has, like, a call...

JAD: First of all, it's "Famous Tumor," okay? You keep calling it "Totally Tumor"....

MARK SALZMAN: Yes. She has a meningioma, a benign tumor, small, about the size of a raisin in the temporal lobe area of her brain.

ROBERT: Right in the same spot where the safety pin fellow had his tumor.

MARK SALZMAN: So the problem for her is, should I have the tumor removed, give up the most satisfying and fulfilling experience of my whole life? Or should I sacrifice my health in order to share with others the experiences that I'm having?

JAD: So we thought, well, Orrin Devinsky, the doctor we spoke with first...

ORRIN DEVINKSY: Yeah. So I think every case is unique in individuals.

JAD: ...he does see patients like this.

ROBERT: This is what he does for them.

JAD: So we took the case to him.

ROBERT: Now, here's the question. If a person comes and says, "I'm having what I want," and you are suspicious that what she also is having is a disease, what do you do about the patient?

ORRIN DEVINKSY: If I knew for sure that the tumor, let's say was benign and would never grow, and the only thing that person experienced was this religious feeling that they found extremely enjoyable, I would say let's do nothing but do serial scans to make sure nothing grows and that you're safe.

ROBERT: But in the book, as it happens, the nun got a little worse. She had a few more headaches, they're more severe. And they took the tumor out.

MARK SALZMAN: "The seizure activity stops. These experiences stop coming and she does feel afterwards a sense of blah. She feels as if she sort of tumbled out of a Himalaya mountain into a muddy village." This is common apparently in patients after they've been treated.

ROBERT: Right. So my last question then is really about the, it seems to me the deepest question of all in this case is that, if someone has a very important and meaningful experience, and you have a sense it may be a abnormality, a physical abnormality that is triggering that, do you regard them as delusional? Like there's just the possibility here that maybe these people are having an actual conversation.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: So Yeah, there's no question ...

ROBERT: Or there are just—you do not even consider that?

ORRIN DEVINKSY: No, I mean, so sci—I think the question you ask and I think you're getting at, is could it truly be that this is God's avenue to speak to us? And people in the late 1800s thought it was through the right hemisphere, and that's often where these cases occur and the right hemisphere. So it may be that, that's right. It's the more emotional hemisphere. And when things are in a perturbed state, you may be more receptive to experiencing spiritual things. And I think there probably is some physiologic basis that allows you to tune into a broader world. And maybe some states of neurologic dysfunction allow you to harmonize or tune in or receive those messages, so to speak.

ROBERT: In which case, then, your tumor or your epilepsy would be the ...

ORRIN DEVINKSY: The window or the conduit, right.

JAD: I—I do feel like I need to place an asterisk right here, like we are talking about a tumor in the end.

ROBERT: Well, but maybe understand that every feeling, every thought you have comes from cells in your brain.

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: If any of those cells can produce a glorious experience, then the experience stands on its own. And sometimes in very well-documented cases, these are extraordinarily profound, desirable things.

ORRIN DEVINKSY: They're often hard to put into words.

ROBERT: Have you tried, I mean, when you ...

ORRIN DEVINKSY: Yeah. I mean, people—you know, Dostoevsky's probably the most articulate person with epilepsy who's had a religious experience and who wrote down what he experienced. I don't have the quote in front of me, but it's, you know, "this Felicity. This—this feeling I get..."

ROBERT: "For several moments," he was quoted to say...

ORRIN DEVINKSY: "Precious."

ROBERT: "I would experience such joy as would be inconceivable in ordinary life. I would feel the most complete harmony in myself and in the whole world, and this feeling was so strong and sweet that for a few seconds of such bliss, I would give 10 or more years of my life, even my whole life, perhaps."

[LISTENER: Hi, this is Emily calling from Rainy Vancouver Washington. Radiolab is supported in part by the National Science Foundation and by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, enhancing public understanding of science and technology in the modern world. More information aboutSloan@www.sloan.org.]

JAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. And our topic today is ...

ROBERT: Totally tumors.

JAD: Yeah, yeah. Totally tumors. Okay.

ROBERT: Well?

JAD: Well, you call it what you want. It doesn't matter. Doesn't matter. Because the topic is tumors. Famous tumors. And our next and final tumor-related tale is one I've been...

ROBERT: We've been wanting to do this particular tumor story for...

JAD: Oh, forever.

ROBERT: Forever?

JAD: Forever.

ROBERT: Like two years ago, I think.

JAD: Oh, longer than that.

ROBERT: Yeah.

JAD: It's a story that comes from a friend of mine, Rebecca Skloot.

REBECCA SKLOOT: You want me to talk? Make noise.

JAD: That's her.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Like, we can move me closer from...

JAD: She's a journalist.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Is that better?

JAD: And she has been wanting to tell this story...

ROBERT: Even longer!

JAD: Since she was in the womb! You know, I mean, she's been researching this story for 10 years.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Hello? Hello. Hello.

JAD: And she just wrote a book called "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks." Now, the story..

REBECCA SKLOOT: Okay.

JAD: Is about a tumor that expands and never stops. Begins in 1950. A Black woman in Baltimore is in her bathroom, and she discovers pretty much all on her own that she has cancer.

REBECCA SKLOOT: It's all—it's a little bit of a mystery how she initially knew this, but she knew it was there. A knot, she called it. She had told her cousins for a while that she thought there was something wrong with her, with her womb, and she climbed into her bathtub and she slid her fingers up inside of herself and found this lump.

JAD: Chapter one.

REBECCA SKLOOT: First, she went into her local doctor.

HOWARD JONES: By chance, I happened to be an attending at that time.

JAD: The guy she eventually ended up seeing, at Johns Hopkins University, was this fellow Dr. Howard Jones.

HOWARD JONES: I'm 98. Next month I'll be 99.

JAD: Wow.

HOWARD JONES: [chuckles]

JAD: So when she came in to see you, can you tell me anything about what she was like?

HOWARD JONES: Well, she was a... uh...

JAD: You don't remember anything?

HOWARD JONES: No, I really don't.

JAD: But you remember her tumor, right?

HOWARD JONES: Oh, absolutely. I never saw anything like it before or after.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And this didn't look like a normal tumor? It was—it was deep purple and...

HOWARD JONES: About as big as a quarter.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Sort of shiny.

HOWARD JONES: Very soft. That was another thing about it. On examination...

REBECCA SKLOOT: Slightly raised.

HOWARD JONES: When you touched it, you might think it was red and jello.

REBECCA SKLOOT: There was something very strange about the way it looked.

HOWARD JONES: There was something worrying about it.

JAD: So doctors took a sample.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah. So they would cut off these little teeny tiny pieces.

JAD: Really small.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Teeny tiny.

HOWARD JONES: A bite or two.

REBECCA SKLOOT: They would take a piece...

JAD: Put it in a tube.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And one would go to the lab for diagnosis.

JAD: And in this case, since it was Hopkins..

REBECCA SKLOOT: They would take an extra piece and give it to a man named George Gey

JAD: Two. So George Gey was a researcher who worked at Hopkins. He had a deal with the clinic that any time they got a patient with cervical cancer, they'd give him a tiny piece of the tumor. What he really wanted to do, his main mission, actually, not just his, scientists everywhere, were trying to do this, they wanted to find a way to grow human cells outside of a human being.

ROBERT: In a dish.

JAD: In a dish.

REBECCA SKLOOT: George Gey had been trying to do this, working on this for decades.

JAD: And why exactly?

REBECCA SKLOOT: It's sort of like—it's sort of like having a little tiny bit of a person in a—in a lab that's detached from them so that you can do whatever you want with them.

JAD: Hmm.

REBECCA SKLOOT: You know, you can't bombard some person with a bunch of drugs and just wait to see how much they can tolerate before their cells all explode. But you can do that in cell culture, so ...

JAD: Oh, so this is like—this is like the basic thing you need to study human biology.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: You need cells in a dish.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yes.

JAD: Problem was anytime they tried to grow human cells in a dish.

MARY KUBICEK: My daughter...

JAD: They would die.

MARY KUBICEK: Yeah, they died.

JAD: This is George Gey's former lab assistant.

JAD: Can you just tell me your name? You know, my name is so-and-so.

MARY KUBICEK: My name is Mary. I'll put my maiden name in there.

JAD: Oh sure.

MARY KUBICEK: Toy Kubicek.

JAD: Mary lives just outside of Baltimore, about an hour from where she used to work with George Gey.

MARY KUBICEK: Oh. This is it. This is Dr. Gey.

JAD: She showed me some pictures.

MARY KUBICEK: And he's sitting at—at a microscope.

JAD: Look at him. He looks—he's—he seems like a really big guy, like a really tall guy.

MARY KUBICEK: He was a big guy.

JAD: At least six five judging from the picture.

MARY KUBICEK: Yeah, he was.

JAD: And in every slide that she showed me, he had kind of a crazy smile on his face.

JAD: Like he's got a—like, he's having time.

MARY KUBICEK: A big bear of a man is what I always thought of.

JAD: Oh yeah.

JAD: In any case, Mary says they were completely stumped at why the human cells always died.

MARY KUBICEK: He was...

JAD: But they just did.

MARY KUBICEK: Yeah.

JAD: So on the day that George Gey walked in, handed Mary a tube with a little chunk of a nameless woman's cervical cancer inside..

MARY KUBICEK: I knew nothing about her.

JAD: No one expected anything.

MARY KUBICEK: No. He was doing the—Well, he probably was ever hopeful. But, you know, I was eating lunch and I thought, "Oh, the heck with it, You know, it's not gonna grow. I'm gonna finish this sandwich."

JAD: Yeah.

MARY KUBICEK: And that's what I did. Then I went in and...

JAD: She gave the cells some food.

MARY KUBICEK: Did my usual.

JAD: Turned on all the machines and left. Came back the next day. They hadn't died. So she came back the next day. And they were growing. And then the next day, still growing.

MARY KUBICEK: They just kept plugging along.

JAD: And the next.

REBECCA SKLOOT: They grew a lot.

JAD: Rebecca says they doubled in size..

REBECCA SKLOOT: Every 24 hours.

MARY KUBICEK: Yeah.

REBECCA SKLOOT: They just grew.

MARY KUBICEK: All of a sudden, you know, I—I kept transferring them, and making more tubes and transferring them, making more tubes and transferring. They were very reliable.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And stronger.

MARY KUBICEK: They just kept plugging along.

JAD: Meanwhile, the woman who had spawned all these cells died.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Right. Officially, she died of uremia, which is like toxicity of the blood because she wasn't able to get rid of the toxic waste that usually goes out in your urine.

MARY KUBICEK: Plugging along, plugging along...

JAD: But not her cells.

[ARCHIVE NEWS CLIP: And to tell us this story, it's a privilege to introduce Dr. George Gey.]

JAD: Wasn't long after that George Gey appeared on TV, holding in his hand a little bottle.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, George Gey: Now let me show you a bottle…]

MARY KUBICEK: Plugging along...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, George Gey: In which we have grown massive quantities of castor cells. ]

JAD: So did you wanna look at the photos?

JAD: You can't really get a sense of how aggressive this tumor was until you go to the Hopkins archives and look at George Gey's pictures and videos.

JAD: Okay, This is the film can here. The HeLa Cell film.

JAD: Then it hits you.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: These are enlarged 10,000 times…]

JAD: Oh my God.

JAD: Swirling hurricanes of cells.

JAD: Just like thousands of little pods.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Some small and some very large.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Clumped together.]

MARY KUBICEK: Kept transferring them and making more tubes.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: See them under the microscope.]

JAD: Looks like something has just exploded.

MARY KUBICEK: Plugging along...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: Undergoing division…]

JAD: That's amazing.

MARY KUBICEK: And they just kept plugging along...

[ARCHIVE CLIP: It keeps getting bigger and bigger.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: Stronger.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: It's indestructible. It's indescribable. Nothing can stop it.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: Why hers just sort of took off and grew and the other ones that they had tried before it didn't, is just a little bit of a mystery. Nobody really knows.

JAD: Four. Nonetheless, George Gey knew what he had. This new cell line was what they'd all been waiting for. So early on, right after this woman died, George Gey sent Mary back down to get more cancer cells from the corpse.

MARY KUBICEK: Oh, he sent me down to the morgue. Yeah.

JAD: Really?

MARY KUBICEK: Oh yeah. So I went down there and the coroner, I don't know who he was. Dr. Gey was there too. And they were standing down at her feet, sort of.

JAD: Yeah. Meanwhile, she's like ...

MARY KUBICEK: She's lying out there, she's already open. I got some samples. Coroner would take 'em out and give 'em to me.

JAD: What'd she look like?

MARY KUBICEK: I couldn't look at her face. I couldn't look at her. The only thing I looked at were her toes and they had chip nail polish on 'em. And that was really like, "Oh, this is a real person."

JAD: What was it about the nail polish that hit you?

MARY KUBICEK: Oh, 'cause it was chipped. 'cause you know that she hadn't been able to take care of her nails for a long time if they got chipped like that. And it showed that she was proud of herself. Not everyone wears nail polish on their toes.

JAD: Yeah, yeah.

JAD: Over the next several months, while this woman's body lay decomposing in the ground, George Gey and Mary produced hundreds of thousands of her cells. Her tumor cells. And he named them the HeLa strain.

ROBERT: Hela?

JAD: Like HeLa, H E L A.

ROBERT: Uh-huh.

JAD: No one would actually know why he had named them that for about two decades.

ROBERT: Hm.

JAD: But what he did with these cells, You know, would—would be unusual nowadays. Like if somebody now found a cell that was special, they'd run off to the patent office and then sell it to Merck for a billion bucks.

ROBERT: Pfft.

JAD: But George Gey?

MARY KUBICEK: He just passed them out freely.

JAD: Didn't try and make any money off.

JAD: He was just..

MARY KUBICEK: Cause it was a nice, nice new thing that could help science.

JAD: Mary says that George Gey began to send HeLa all over the world.

MARY KUBICEK: Yep.

JAD: And pretty soon she was in hundreds of labs.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And you know, this was in the midst of the polio epidemic.

[ARCHIVE NEWS CLIP: This is the season when polio is at its worst.]

JAD: We're talking early fifties, right?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah. So there's 1951-52. You know, schools are being closed, kids are being kept inside.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: To this cruel disease, medical science still has no complete answer.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: There was this enormous effort to develop a polio vaccine.

JAD: Problem was, in order to develop a vaccine, you had to have enough polio virus, you know, enough quantity to be able to study it in a lab. And they had no way of making enough.

ROBERT: So what do they do?

JAD: Well, one of the guys that Gey—one of the guys that Gey had sent the cells to..

ROBERT: Yeah.

REBECCA SKLOOT: This collaborator friend of Gey's.

JAD: Discovered something kind of amazing. Which was that polio loved the HeLa cell. Put polio inside a HeLa cell, HeLa would copy, and in the process make more polio.

ROBERT: So it's the super Xerox cell no matter what you wanna do it. Like "make a copy, make a copy, make a copy."

JAD: Yeah. So now they had a way of making polio.

REBECCA SKLOOT: HeLa could just be a polio factory.

JAD: And so the government made a factory.

REBECCA SKLOOT: At the Tuskegee Institute.

JAD: A real one.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Literally a factory. So they had these big, you know, stainless steel vats of culture medium that were sort of rotated constantly. Autoclaves for sterilizing all their equipment. A row with, you know, a four or five microscopes, crazy Frankenstein-ish gizmos. They had this machine that was like an automatic cell dispenser and it had this sort long mechanical arm. It'd squirt a certain amount of this culture medium filled with HeLa cells into a tube.

JAD: Wow. This is like the beauty of industry right here.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah, it is. Absolutely.

JAD: And the cells that were produced at this factory, she says, were used to test the polio vaccine.

[ARCHIVE CLIP: A potent vaccine to prevent the dreaded disease.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: The tests that they were doing in [unclear], it was the largest field trial ever done. At its peak, the Tuskegee HeLa Production Center was producing about 6 trillion cells a week.

JAD: Wow.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Which is kind of inconceivable.

JAD: But that was actually only the beginning, says Rebecca, because this factory led to an even bigger one. It was for profit.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Right.

JAD: And that second factory ...

REBECCA SKLOOT: Was the first time any human biological material was commercialized.

JAD: So this was the first biotech company?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah, basically.

JAD: Okay. But when they first started mass producing HeLa...

REBECCA SKLOOT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: ... what sorts of things were done to these cells? What sorts of problems were investigated?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Like anything you can imagine. So they infected HeLa cells with every kind of virus. Hepatitis, equine encephalitis virus, yellow fever, herpes, measles, mumps, rabies, whatever, like you just—any—any vaccine. And this was just an—just a revolution for scientists. There was research on chemotherapy drugs. HeLa cells went up in some of the first space missions.

JAD: Really?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah. So they were...

JAD: HeLa went into space?

REBECCA SKLOOT: HeLa went into space, which every time I hear, I think like "HeLa... in... space..." [laughs]

JAD: [laughs] And why, I mean just 'cause?

REBECCA SKLOOT: The premise was to see what happens to human cells in zero gravity. You know, if we're gonna be sending people up into space, what's gonna happen to them up there?

JAD: Yeah.

REBECCA SKLOOT: So HeLa went up before any humans did. And then she eventually went up. She—the cells. There was...

JAD: Actually, that was an interesting little slip up there.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah, I know. [laughs]

JAD: Okay, so let's actually skip forward in the story to the point where that, that slip up, you just heard, that pronoun confusion gets personal, you know?

ROBERT: Wow. Well, what happens?

JAD: Okay. It's the late '60s.

ROBERT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: And HeLa has led to a revolution in science. And now there are hundreds of cell lines, not just HeLa, but hundreds. And somewhere along the way, scientists discover that HeLa is so aggressive that she's actually been contaminating and taking over all of these other cell lines.

ROBERT: Well, you just said "she," but I get your point.

JAD: And she—and she does—it in the—"it" does it in the strangest way.

REBECCA SKLOOT: HeLa cells can, you know, they can float on dust particles. They can write on ...

JAD: They can what?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Um ...

JAD: They can ...

REBECCA SKLOOT: They can ...

JAD: ... float on dust particles?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah. So they can ...

JAD: You mean they can hop out of a dish and just get on a particle and just float?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Mm-hmm.

JAD: Out the door.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Up the stairs.

JAD: Down the hall.

REBECCA SKLOOT: One HeLa cell ...

JAD: Into a lab.

REBECCA SKLOOT: ... drops into ...

JAD: Into a dish.

REBECCA SKLOOT: ... a cell culture where there's other cells growing. And because HeLa cells are sort of powerful cells, they take over.

JAD: So on the heels of this catastrophe, someone at Hopkins decides to make a test. Let's make a test that will allow us to genetically determine if a cell is HeLa or if it isn't. And to make a long story short, this desire for a genetic test led scientists and then journalists to ask a question, which amazingly for 25 years had not been asked, Who was this woman? And that's when we found out her name. Henrietta Lacks.

JAD: This is the sound of Rebecca reading Henrietta's medical records for the first time.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: "This is a 30-year-old colored woman."]

JAD: She's sitting with Henrietta's youngest daughter, Deborah.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: This is the second of November. So this is again, when she was pregnant with you.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Mm-hmm.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: Right?]

JAD: Henrietta had five kids when she died at the age of 31. Most have no memory of her 'cause they were too young. That's especially true of Deborah.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: It does. I was only 15 months old and I don't remember anything about my mother.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah. So she, you know, she—she had spent her entire life just sort of longing to know who her mother was and did she like dancing?

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: You know, I always wanted to know what she liked to do, what she went, what she liked to eat.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: Did she breastfeed Deborah? She—she was really sort of almost fixated on that idea. She wanted to know if she was breastfed.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Oh, I don't—you know, I don't know what I would give up just to—just to have her here. I'll tell you. Just to see her and hold her.]

JAD: So in 1973 when a scientist calls the Lacks family and Deborah hears that little bits of the mother that she never knew are still alive? And, "Oh by the way, can we take a blood test from you and your family? ‘Cause we're having some contamination problems. We need these genetic markers, blah, blah, blah." Well, as you could imagine...

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Took me by surprise. It really did.]

JAD: It was really confusing.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: I mean, how much is the—how much of our cells is out there? You know?]

JAD: Eventually she went online, did some searches. And found...

REBECCA SKLOOT: Thousands and thousands of hits.

JAD: Like for instance, on HeLa clones.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And Deborah had heard, you know, various journalists in the past had come to her and mentioned, you know, Dolly, the clone sheep and said, you know, your mom, they did this with your mom too. Meaning that's actually where the technology started. The first cells ever cloned were HeLa cells. But that was just cloning a cell, not cloning an entire being. But that distinction is very complicated, particularly for somebody who doesn't know what a cell is.

JAD: Yeah.

REBECCA SKLOOT: So Deborah, between what journalists had told her and Googling "Henrietta Lacks and clone" thought there were thousands of clones of her mother around. And...

JAD: Really? You mean like a bunch of Henriettas?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Thousands.

JAD: Walking the streets?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Walking around.

JAD: And Rebecca says that one of Deborah's biggest fears was bumping into one of these clones.

REBECCA SKLOOT: She said, you know, she would say, "I—I would have to go talk to her, and she wouldn't know that I was her daughter. And—and—and I don't know that I could handle that."

JAD: Wow.

REBECCA SKLOOT: It sounds so fantastical. Like how could someone believe that there are copies of her mother walking around? But at one point, 25 years after their mother died, someone called and said, "Hey, part of her's still alive. And you know, we've grown enough of her so that it could wrap around the earth several times."

JAD: At that point, all bets are off.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah, right. Exactly.

JAD: Not to mention that it's actually not that crazy. Because your DNA is in your cells. So if your cells are taken outta you and they still grow, well, isn't that still you? Alive?

ROBERT: It's of you, but it's clearly not you. And then yet it's going on and on. That's—It's a funny middle space, that's for sure.

JAD: Yeah. So here's what happened. As Rebecca went off in search of Henrietta Lacks, every so often Deborah would come along and sit with her as they interviewed, you know, anyone they could find friends, family, and eventually over many, many years, a picture does emerge of who this woman was.

REBECCA SKLOOT: She was born in—in Roanoke.

JAD: 1920, Virginia.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And I think she was the 10th of the 11 children.

JAD: But apparently she was the one that stood out.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Everybody talked about her as just being, you know, she was the catch.

SADIE STURDIVANT: Oh my goodness. I don't think I could top her.

JAD: This is Sadie Sturdivant, Henrietta's cousin.

GLADYS LACKS: Henri was a beautiful girl. I was beautiful myself, but Henri was very pretty. Brown eyes, long hair.

JAD: And this is Henrietta's sister, Gladys.

GLADYS LACKS: No tan complexion.

JAD: Everyone that they spoke with zeroed in on the same few points. Like first...

REBECCA SKLOOT: She was really meticulous about her nails.

JAD: Always painted 'em red.

REBECCA SKLOOT: This very deep red.

JAD: And second, Henrietta just had this..

REBECCA SKLOOT: She was very ...

JAD: Strength

REBECCA SKLOOT: ... forthright. Very sassy.

JAD: Like her cells.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JAD: Now the unfortunate thing is that when it comes to her life, you know how she lived, There's not a ton of detail.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: Right? October, so this is when she first went in with her cancer.]

JAD: But in that hotel room, when the two of them were flipping through the medical records, they did start to get some detail.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Okay, Now here's her autopsy.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: Right.]

JAD: About how she died.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: These are things I wanna take notes about.]

JAD: Was she in a lot of pain when she died?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah. Her—this was the hardest thing. She was eventually in an unbelievable amount of pain.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: She complains of pain in the right lower quadrant.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: Wailing and, and crying and, you know, moaning for the lord to help her. And…

JAD: According to the records, doctors tried everything.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Morphine, they injected a hundred percent alcohol straight into her spine.

JAD: Wow.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: Complains of pain, in spite of the alcohol injection last week.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: And she would have these fits of pain, through spasms where these waves of pain would hit her and she would rise up out of the bed and thrash around. So they strapped her to the bed and her sister, well along with one of her friends, you know, one of them would tighten the straps and the other one would put a pillow in her mouth so that she wouldn't bite her tongue.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Just to—if I only just had the chance to take care of her.]

JAD: Now, dealing with how her mother died was one thing. But the cells made it more complicated.

REBECCA SKLOOT: For Deborah, her—her mother was alive in these cells somehow. So if that's true, that left very big questions. And the first of them, for Deborah was, how can Henrietta rest in peace if part of her, with part of her soul is being, you know, shot up to the moon and injected with all these chemicals and radiated, and bombarded.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: It was just so painful knowing, you know, they had her cells on the back of a donkey going to Turkey. You know, in the airplanes just going all over the world. I—I—I just don't know.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: She worried about them. She worried that it hurt her mother...

JAD: Yeah.

REBECCA SKLOOT: ... when you infect the cells with Ebola, does somehow her mother feel the pain that comes with Ebola?

JAD: And had a scientist ever, like, sat down with her?

REBECCA SKLOOT: No.

JAD: No. I mean, just explain to her like this is ...

REBECCA SKLOOT: No. No, never. Nothing.

JAD: Because it—it just strikes me that it wouldn't be that hard to explain that, like, when you take cells out of a body, it's kind of like when you cut your fingernail off, it just doesn't ...

REBECCA SKLOOT: But your fingernail doesn't keep growing and living after you cut it off. It's a—it's really hard. There is no other example of some way that you can take something from someone's body and have it keep living and not have a person feel it.

JAD: And all these worries, says Rebecca, began to build in Deborah's mind. And build and build.

REBECCA SKLOOT: There came this point, we—so we were at her cousin's house.

JAD: This is her cousin Gary.

REBECCA SKLOOT: She was broken out in hives. And she was telling him all the stuff that she'd recently learned.

JAD: You can almost hear it on the tape. She says to him..

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Leave it there.]

JAD: She can't carry the burden of these cells anymore. She can't do it.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: I can't cry no more. I don't wanna cry to them no more.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: And I had been sort of trying to talk her down and he was trying to talk her down.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: [unclear]]

REBECCA SKLOOT: And then just out of nowhere, he just started singing

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gary [singing] I know the Lord did good, yo, I know the Lord did good, He put food on my table, I know the Lord did good.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: And he started preaching.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gary: There are some things that doctors cannot do.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: He held her head in his hands.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gary: And we come to you tonight, the author and the finisher of our faith. And we thank you for being a wait maker. God, you make a path in the mighty water. You called the mountains of skip leg rams and, and the little heels like lambs. We thank you today.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Thank you Lord.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gary: Thank you for that.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Thank you, Lord.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gary: Thank you.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Thank you Lord.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Gary: Thank you.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Thank you Jesus. Hallelujah, hallelujah, Hallelujah. Hail Mary. Amen. Thank you. Amen Thank you.]

REBECCA SKLOOT: And she just relaxed.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Feel lighter, man, I feel light. [sighs]]

JAD: She didn't realize it then, but that night Deborah was on the verge of a stroke.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: You wanna walk up and see the building?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: You wanna walk? Okay.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: You—He said it's just up this hill. Yeah.]

JAD: One of the most striking moments of this story is when the two of them visit Hopkins.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: So how do you feel?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Fine.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Rebecca Skloot: Yeah?]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: So far so good.]

JAD: And Deborah meets her mother's cells for the first time.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Christoph Lengauer: I—I'm gonna show you that room and I can show you the cells.]

JAD: Because the scientist had finally contacted her.

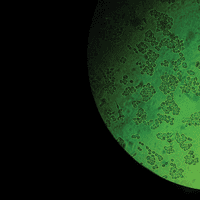

REBECCA SKLOOT: Christoph Lengauer, the scientist who invited us into his lab to see the cells, he had projected them onto a screen.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Christoph Lengauer: Don't be confused, they look green here. Okay? ]

REBECCA SKLOOT: They're sort of neon green in this particular case 'cause of the way they were stained and projected. So they're very ethereal looking. They're very sort of, they're, they glow, you know? I mean, when you think about angels, right? You think of something glowing. Christoph turned on this screen and she just, you know, I mean, Deborah just gasped. She just, ugh.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Oh my God.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Christoph Lengauer: This is about 200 times bigger than what they really are.]

JAD: A swirling hurricane of cells.

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Wow.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, REBECCA SKLOOT: Did you say "Oh, that's my mother."]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: Yeah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, REBECCA SKLOOT: Pretty good, pretty good yeah.]

[ARCHIVE CLIP, Deborah Lacks: It's hard to leave. Oh my God].

REBECCA SKLOOT: Christoph gave—he gave her a—a vial of these cells that she could hold in her hand. And they came out of a—out of a freezer. So they—they were very cold and she sort of, you know, rubbed her hands together with the vial in her hands to sort of warm them up and sort of blew on them to keep them warm. And then she just sort of whispered to the cells. It was sort of incredible. She just raised them up to her lips and she said, "You're famous, but nobody knows it."

JAD: Just a week before Rebecca and I spoke in the studio, she got a call that Deborah had died.

REBECCA SKLOOT: She had a heart attack and died in her sleep.

JAD: Okay, so as you may know at this point, that segment was based on Rebecca Skloot's book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. It's an amazing book. It came out right when we released that piece. It's been a couple years now, and recently we met up with Rebecca in Chicago just to get an update.

REBECCA SKLOOT: It's like the book came out and then ...

JAD: Because since the publication of that book and then ...

REBECCA SKLOOT: ... the whole story just sort of exploded.

JAD: It just took off. Scholarships were named after Henrietta.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Henrietta was given an honorary doctorate.

JAD: Monuments.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Highway placards and historical landmarks and buildings named after her. There's a high school called Henrietta Lacks High, HeLa High for short.

JAD: Meanwhile, the book is exploding. She went on this, like, insane book tour. Members of the Lacks family began to join her.

REBECCA SKLOOT: It started off with just Sonny Lacks would go and do a sort of onstage Q and A. And people started cheering. And scientists standing up saying, "I want to tell you what I did with these cells, and I want to tell you why this was important for me. And I'm sorry it was hard for you." And people reaching out. "I'm alive today because of this drug that your mother's cells help develop." Or, you know, "I do this in my lab." I mean, they just—it never stopped. It was just a flood.

JAD: Which is in a way, what Deborah always wanted.

REBECCA SKLOOT: She wanted to go to every event. She wanted to be on every television show. She had her dress picked out for Oprah, like, you know, eight years before the book came out. You know, she was. Deborah wanted this. This is exactly what she always dreamed of.

JAD: But then just last year, something interesting happened—interesting and troubling.

REBECCA SKLOOT: So, yeah. So March, 2013, this group of scientists from Germany sequenced the HeLa genome and published it online where anyone can download it. You just click a button. I downloaded it. It was just there. And they did not ask the family. And my initial reaction when I saw this press coverage was they did what? Because within the HeLa genome, there was also Henrietta's genome. And some of that was—50 percent of that was passed on to her kids and 25 percent potentially to her grandkids. But one of the things—so they put out a press release when this genome was sequenced, and on it, it had a little, you know, frequently asked questions that the press might wonder about. And one of them was, "Can you learn anything about Henrietta or her children from this genome?" And the answer was, no, can't learn anything about them.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And I do—and I believe that they believe this, but this is a misconception. You can, in fact, learn about people, and in fact, you cannot even hide people's private information if you try. And so one researcher took the genome and created essentially a report on Henrietta's genes. You have X percent chance of bipolar disorder, alcoholism, obesity. You know, just has this huge range of things. And some of it is yes, there's some real potential privacy violation, like with the Alzheimer's genes and things like that. Bits of information about your family.

ROBERT: Did Henrietta have ...

REBECCA SKLOOT: I will not tell you. [laughs]

JAD: Well, this report that this dude made, did he list all of these things you're describing?

REBECCA SKLOOT: So—and he sent it to me. So I called the Lacks and said, you know, "Did you know this—anything about this?"

JERI LACKS-WHYE: And Rebecca had called.

REBECCA SKLOOT: You know, they did not.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: And it kind of bothered us because we're saying okay, why wasn't the family involved with this decision making?

JAD: That was Jeri Lacks.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: Jeri-Lacks-Whye.

JAD: Henrietta Lacks's granddaughter.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: Back in the '50s, you had Henrietta Lacks. Her cells were removed without her family's knowledge. Then you go in the '70s, my dad and his siblings, they took blood samples, used it for research. They didn't give consent. Then you come 2013, and you have Henrietta's—I felt as though it was her medical records being published publicly.

REBECCA SKLOOT: You know, their first question was, "Can you get them to take it down so we can figure out what it is, what it means?" So I reached out to the scientists and said, "The Lacks family, you know, has asked that you take this down." And they replied immediately. They took it offline immediately. And then I contacted Francis Collins, who's, you know, the head of the NIH. I also reached out to Kathy Hudson, who used to run the Genetics and Public Policy Center at Hopkins, and is now over at the NIH dealing with a lot of these issues. So I reached out to them and said, "Somebody needs to try to just help the Lacks family get consent. Somebody needs to just go back, pretend like this is starting now, and just do what probably should have happened in the first place."

JERI LACKS-WHYE: And that thing might have been like a couple of weeks after that, several weeks after that, that we had a meeting with NIH. It was my mom, myself, my sister, my dad, my uncle, my brother David, my sister Kim, my cousin Ron, Rebecca Skloot. She was actually on a conference call.

REBECCA SKLOOT: All the NIH folks drove up to Baltimore.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: We googled their names. Dr. Collins and Kathy and the guys sitting there, was like, oh, we were kind of—we was excited. Like, okay, yeah, we sitting in a room with the director.

REBECCA SKLOOT: They all met.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: Just to listen to everybody, you know, listen to our concerns, listen to our questions. What can be done? What can't be done?

REBECCA SKLOOT: The Lacks family asked about everything you could possibly imagine.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: Went over, you know, the information about genome, gene mapping, sequencing.

REBECCA SKLOOT: Just the basic science of genomes.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: To get a clear understanding of what the genome meant to science. We don't want to stop science, but yet we don't want certain information to be just broadly available publicly.

REBECCA SKLOOT: So they laid out three options. One was we don't release any of them at all. And then there was a second option which was release it with no restrictions, just put it out there like the Germans did. And then there was a third option which was release it with restrictions. So the NIH would house it on their own servers, and that in order to get access to it, you would have to send in an application that said this is the research we're gonna do. There would be a committee formed that was a group of scientists and then some members of the Lacks family.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: The HeLa Genome Committee.

REBECCA LACKS: One grandchild and one great grandchild.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: My brother David and my cousin Veronica.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And obviously this is the option they picked. So yeah, there's this committee and they just a few weeks ago saw their first batch of applications, and then the news hit and it was the first time that they were part of the news. So ...

JAD: They, the third generation?

REBECCA SKLOOT: Yeah, the Lacks family. Like, Jeri Lacks was on MSNBC Live doing an interview about this. And, like, she'd never done this before and, you know, they were in every newspaper. I mean, it was everywhere.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: Yeah, it's pretty exciting. Yeah. We are stepping into the spotlight. It's the grandchildren.

REBECCA SKLOOT: The third and fourth generation of Lackses.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: It's the great grandchildren.

REBECCA SKLOOT: This is their story now. And that's—you know, the other thing that is an undercurrent through all this is Deborah's gone.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: She was the one who was just so forceful and so dedicated with getting the information out there about her mom.

REBECCA SKLOOT: And, you know, when I look at the four years since the book came out, you know, there are a few moments that stand out as incredibly emotional ones for me, having to do with Deborah. But this—the first meeting, sitting on this speakerphone, listening to this meeting.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: These high officials, sitting at the table and have sincere concern about our questions.

REBECCA SKLOOT: If she could have said, "What do I dream might someday happen?" That would be what she would have described.

JERI LACKS-WHYE: I can—I can just imagine her just sitting there, and she is just laughing, rocking back and forth, twiddling her—her fingers, saying, yay, just absorbing all of this, this excitement.

JAD: Before we close, I wanna thank Rebecca Skloot for giving us her raw tapes. Her book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is truly spellbinding. You can get more information at Radiolab.org. Sign up for our podcast there, Radiolab.org.

JAD: I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: Thanks for listening.

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.