Feb 25, 2014

Transcript

JAD ABUMRAD: Hey, I'm Jad Abumrad.

ROBERT KRULWICH: I'm Robert Krulwich.

JAD: This is Radiolab. And today ...

ROBERT: Well, it's stories about confrontations.

JAD: Throwdowns.

ROBERT: Faceoffs.

JAD: Smackdowns.

ROBERT: We're calling it What's Left When You're Right.

JAD: And now, at last, that title will make sense.

ROBERT: I think it will, because now we have a story about a fight that starts in a cage, spills over into the human species as a whole, and turns out in the end to be nested inside the brains of every single one of us.

JAD: Oh!

ROBERT: And that story comes from our producer Pat Walters.

PAT WALTERS: It all started for me with this essay that I read by this guy named Jonathan Gottschall.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: I'm a writer.

JAD: And a fighter.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: And a bad, bad man.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: So a few years ago, I'm an English teacher. I'm sitting in the English Department, I'm sitting in a cubicle.

PAT: He was a teacher at a small college outside Pittsburgh. And at the time Jonathan had written some articles, even a couple of books.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: But I was still an adjunct, a lowly adjunct. You know, the academic equivalent of cheap migrant labor.

PAT: Pretty low on the totem pole.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: So I was sitting there in the cubicle that I share with other adjuncts, just kind of feeling miserable, down about my job. And then I catch a glimpse of movement through the window, and I go to window and I look out.

PAT: And he notices that across the street where there used to be a car parts store ...

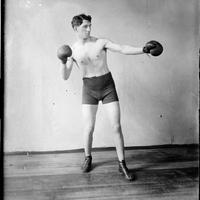

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: This new business had opened up, a mixed martial arts gym. This cage-fighting stuff that you see on TV.

JAD: That they're like—the kind where you can—where anything goes? Like, that kind? Or ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Anything goes, yeah. Punching, kicking, mean, ground and pound. You can climb on top of a guy and punch him in the face until he goes out.

JAD: That stuff is just too raw.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Well, I had been watching it guiltily and very much in the closet for about 15 years. I knew it was wrong. I watched it in the way that most men watch porn. You know, my wife would walk into the room when I was watching and I'd really quickly turn the channel.

PAT: But now there they were, these huge muscle-bound dudes in the picture window right across the street.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: They're in the cage, they're hitting each other, they're tackling, they're fighting on the ground.

PAT: And as he watches them day after day ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: I start to envy them. I envy their bravery and the way they just seemed so alive, while I was in my cube rotting.

PAT: Until one day he decides ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: I decide to do it.

PAT: I'm going over there.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Now I'm not a tough guy. I'm an English professor. I'd never been in a fight before but I wanted to try to do a brave thing.

PAT: Did you—did you tell your wife?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Yeah. Yeah.

JAD: And what was your wife's reaction?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: This is almost a perfect paraphrase. She said, "You will be killed. You have no skills."

JAD: [laughs]

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Yeah, it kind of hurt. It hurts to find out your wife has no respect for your fighting prowess..

PAT: But that doesn't stop him.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: No.

PAT: He starts training, sparring with other beginners.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: And this is how it all goes down. Maybe I'm four months into my training. Let's say I'm about four months into my training. And I feel like I'm starting to get the hang of things. I'm starting to feel more confident, and I'm doing pretty well against the other beginners and the sort of the weaker guys in the gym. So one day I go into the gym, and it turns out I'm gonna spar this guy named—named Nick. And I'm a little concerned about it because he's been at the gym longer than me. But I'm not all that concerned because I've watched Nick. We all watch each other in the gym. And he's just not an athlete. He even says this himself, he's kind of a klutzy guy. He's awkward in his movements, a little bit—a little bit stiff. And I felt that just, like, athletically I stacked up very well with him. I was faster than him. I thought I'd get around better. And so, you know, we go into the cage and the bell rings and, you know, we go to the center of the cage and we engage. And again, I'm feeling confident.

PAT: And then ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: He punches me hard in the face.

PAT: Then he hits him again.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: The punches keep coming. Jab, cross. Jab, cross. Jab, cross. Jab, cross. Hook. He doesn't bob, he doesn't weave, he doesn't dance. He's right there in front of you, you should be able to hit him, but I can't. He's just hammering me.

PAT: Finally, the bell rings.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: And I go collapse in one of the chairs, and my headache is already thudding in my brain. And I say to myself." Well, that seals it. The—the Faurie-Raymond hypothesis has to be true.

ROBERT: The 40 Raymond hypothesis has to be ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Faurie.

ROBERT: Oh! The Faurie-Raymond. I see.

JAD: So, okay. What's is ...

ROBERT: What is the Faurie-Raymond hypothesis?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Okay. So Faurie and Raymond are these French researchers ...

PAT: Okay, so before we get down to the two French researchers, we should say that Nick, that guy Jonathan fought?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Nick is a lefty. Nick is a lefty.

PAT: And Jonathan is a righty.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Mm-hmm.

PAT: And this conflict between lefties and righties, it goes way back.

DAVID WOLMAN: Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

ROBERT: Just ask David Wolman.

DAVID WOLMAN: I'm an author and journalist in Portland, Oregon.

PAT: You're right-handed, right?

DAVID WOLMAN: No. I am very left-handed.

PAT: Said that like you wanted to kill me.

DAVID WOLMAN: [laughs] I was trying to. I was trying to get it out that way.

ROBERT: Like Batman defends, you know, against crime? David is a defender of lefties everywhere.

DAVID WOLMAN: I am a strong left-hander. If you look at the Edinburgh handedness inventory, I'm like a 10 out of 10.

PAT: I did it. I'm a very strong right hand. I'm, like a—I got, like, a perfect score for right-handedness.

DAVID WOLMAN: Okay. Well, our friendship is over now.

PAT: David's kind of joking, but he actually wrote this whole book called A Left-Hand Turn Around the World, because ...

DAVID WOLMAN: Growing up as a kid in a family of right-handers ...

PAT: David says he always felt a little different. Or as his family used to put it ...

DAVID WOLMAN: You're special, and this is—this is some little extra sprinkle of specialness in you. Luckily, they're not—you know, they didn't grow up in the Middle Ages and think that I was cursed by the devil and therefore I'm left-handed. Because throughout the ages, and pretty much throughout every culture, left-handers were perceived as evil and sinister.

ROBERT: In fact, the word sinister itself is derived from a Latin word, which means "on the left side." And in English, when we say something is correct we say it's right.

DAVID WOLMAN: You know, in the Bible, God is always doing really nice and benevolent things with the right hand and not so nice or benevolent things with the left hand. Everything left is always ugly or lesser or different or worrisome. And the presumption was that if this was not the result of a curse by—from the devil, then this was the result of poor parenting or poor posture.

PAT: But we know now that ...

DAVID WOLMAN: No.

PAT: It's genetic.

DAVID WOLMAN: When you do a genetic study and you look at parents ...

PAT: Here's how it plays out.

DAVID WOLMAN: If you have two right-handed parents, their chance of having a left-hander is about nine and a half percent. If you have one righty one lefty parent, the odds do go up.

PAT: Now you've got ...

DAVID WOLMAN: 20 percent. Almost 20 percent chance. Then two southpaw parents have a 26 percent chance of delivering into the world a southpaw.

PAT: And if you add up those chances and look out across the entire human species ...

DAVID WOLMAN: We are about 90 percent right-handed, 10 percent left-handed.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: 90 percent of people are right-handers.

PAT: Which brings us back to Faurie and Raymond.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: So Faurie and Raymond realize that left handedness is this sort of evolutionary mystery.

PAT: Jonathan says it's a mystery, at least in part because left-handedness seems to come with some disadvantages.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: It's associated with all these negative health outcomes, and I actually wrote a few of them down. Higher risk of schizophrenia, immune deficiency, epilepsy, learning disability, spinal deformity, ADHD, alcoholism, dyslexia, psychopathy, Crohn's disease. That's not even a complete list.

JAD: So wait, lefties have a higher incidence of all these things?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Yeah, significant.

ROBERT: How much higher? Like a teeny bit higher?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Teeny bit. Teeny bit.

PAT: Like, a really teeny bit.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: But evolution works on teeny bits, right? So if there are significant health costs to being left-handed, why hasn't natural selection trimmed it away?

PAT: Why do we still have lefties at all? That's the puzzle. And the Faurie and Raymond hypothesis is that we still have lefties in the world because they have an advantage in one arena.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Combat.

PAT: Which is what Jonathan realized in the ring with Nick.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: You get very used to fighting right-handers. You get used to where the punches are coming from. And then you face the left-hander, and they do everything backwards, and you have to develop basically a whole different approach to fighting.

PAT: And if you go back to a time when wars were won and lost largely because of hand-to-hand combat ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Whether with fists or with spears or with clubs or whatever.

PAT: Maybe the ancient lefties like Nick had a little edge.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Maybe the survival advantage of battling left-handed washed out those survival costs associated with being left handed.

PAT: So Faurie and Raymond came up with this prediction.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: A prediction based on their idea.

PAT: That if left handedness is somehow linked to fighting prowess, then ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Wherever they go in the world, they will find that the most violent societies have the highest proportion of lefties.

JAD: What—how would they define violent? Like, over time? The number of wars or what?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Numbers of wars, homicide rates, that kind of thing.

JAD: I see. Huh.

PAT: So they dug up some data on violence and left-handedness in three different tribal societies. Then they went out and did their own field research in five other groups.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: And they find this beautiful correlation. The least violent society in their sample had three percent left-handers. The most violent societies in their sample, tribal societies in New Guinea that were notoriously violent had rates of left-handedness about 25 or 30 percent.

ROBERT: Whoa!

JAD: Whoa!

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Yeah. It was this incredible ...

JAD: Three times as many lefties as us, I guess?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Yeah. Yeah. So it seemed to be true.

PAT: Case closed. No.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: No.

PAT: Here's the thing. That tribe from Papua New Guinea that had three times as many lefties as you would expect? That was data that they looked up in the library. But when some other scientists actually went in the field and checked it ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: They found no evidence that lefties were over-represented in this tribe.

ROBERT: It wasn't heavily lefty.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: According to this study, they just didn't find any evidence that lefties were over-represented.

JAD: I'm disappointed, because this was a very cool idea.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: I was disappointed too. But I think we can salvage it. The original ...

PAT: Here's where Jonathan had an idea of its own. After Nick knocked him out, he thought maybe looking at real battles, real violence, maybe that was where Faurie and Raymond went wrong.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Maybe lefty genes are maintained more through success in the play fights of sports than in actual no-holds-barred violence.

PAT: Maybe it's about sports not war.

ROBERT: In fact, actually lefties have long been known for doing better at all kinds of different sports: tennis, boxing, baseball. We looked at a Northwestern study, Jad, which found that 50 percent of the top players in baseball, highest RBIs, best pitchers ...

JAD: Wait, 50 percent are lefties?

ROBERT: Yes. And you see this same over-representation of lefties in any sport that's got a one-on-one component, you know, a faceoff kind of thing. The only scientific question you need to ask is ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Do athletes have more children?

JAD: Oh, wait a second. So you're saying all those lefty pitchers that are really good and that screw up the right-handed hitters, maybe they're having so many kids ...

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Yeah.

JAD: ... and that's what keeps that 10 percent 10 percent?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Well, sort of. Yeah, so but ...

ROBERT: We can check this. Lefty Gomez, New York Giant left-hander has 16 children.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: So people—so people have actually looked into this. You know, they've looked into it. Do athletes do better with the ladies? And the evidence is pretty strong that they do.

ROBERT: Really?

JAD: Really?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Anybody who went to high school—you went to high school and college.

JAD: Well, yeah. That seems like duh. You don't need a scientist to tell you that.

ROBERT: We have to count the babies. Count the babies. Are they counting the babies?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Or you can—or you count the reproductive opportunities.

JAD: What do you mean? Like, how many dates they go on?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Yeah, exactly. How many sex partners they have.

ROBERT: Why not count the babies? You don't want to count the babies?

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Well, because we live in an era of birth control now, and so it's—and the environments in which these traits evolved, there was—there were no reliable means of birth control. So we use reproductive opportunities as a proxy for reproductive success.

JAD: And then—okay. It's starting to make sense to me now.

DAVID WOLMAN: How could I lovingly say that sounds like total garbage?

ROBERT: You'd think David would love this idea. He's the lover of lefties. But no.

DAVID WOLMAN: It's just there's too much biology at play here. So—and too much ancient, prehistoric biology at play for this to matter as much as your dear English professor friend wants it to matter.

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: But here's—here's the thing. Whether or not this has been proven scientifically, personally I know it's true.

ROBERT: [laughs]

JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: I know it's true because I experienced it. I know it's true in a way that statistics can't touch, you know? I know it's true from being in that cage, having the undoubtable truth just pounded into my brain literally by my friend Nick. You know, I know it's true. Yeah.

DAVID WOLMAN: I mean, it's so fun. These kind of things are so fun because it's so easy, right? I mean, who doesn't love an easy answer? But it seems so far-fetched and maybe that makes me a little bit of a wet blanket, but after this year plus investigating this topic ...

PAT: David says about halfway through writing his book, this whole handedness puzzle kind of flipped for him. Instead of worrying about why lefties have stuck around, he started to wonder about that 90/10 number. Like, why in humans do lefties only make up 10 percent of the population when in pretty much every other creature on Earth ...

DAVID WOLMAN: This asymmetry is random. In other words, it's a coin flip whether a monkey in South America is going to be left- or right-handed.

PAT: Several studies have shown that it's about 50/50 in cats. Same is true for dogs. People have looked at mice, toads, various kinds of birds, and all of them have a pretty even split.

DAVID WOLMAN: It looks like what is unique to humanity is the 90/10.

PAT: So how did we end up at 90/10?

DAVID WOLMAN: Well, one of the strongest theories for the origins of handedness, hooks handedness onto left hemisphere dominance for speech.

ROBERT: The idea, says David, is that humans are—way back in the day, so these would be, like, early humans, pre-human ancestors were 50/50s. That is, they were 50 percent righty, they were 50 percent lefty like all the other animals in the forest. So the things that our brains were doing back then were also even on both sides. So the motor cortex on the left controlled the right hand as it still does, the motor control on the right controls the left hand as it still does. But then ...

DAVID WOLMAN: At some point in our evolutionary history ...

ROBERT: Language begins to develop.

DAVID WOLMAN: And there was this shift in brain organization.

ROBERT: The part of the brain that controlled speech, I don't know why this happened but it began to move over to the left side of our brain. According to one theory, that shift ended up making the left side of our brains better at motor control. Because think about what speech is. I'm going to say, "Let's pick a pair of pickled peppers."

JAD: Mm-hmm.

ROBERT: My tongue, my lips, my teeth are all in a medley of complex motion there. That is all about motor control. So the left side of my brain is doing that, and it's getting bigger and stronger. As the species gets more and more speech-y, it gets more and more left brain or right-handed.

JAD: So you're saying that as speech grows on our left side, the motor cortex grows on our left side. And since the left motor cortex controls the right hand, the end result is a bias to the right.

ROBERT: Yes.

PAT: But weirdly, buried somewhere deep in our DNA still ...

DAVID WOLMAN: Is this gene that confers the chance to become left-handed.

PAT: Which results in about 10 percent of the population being lefties.

ROBERT: But they're not dwindling though. They just seem to stick there.

PAT: Well, they don't seem to be dwindling in the—in the blink of an eye, that is ...

DAVID WOLMAN: We're not! We're not dwindling!

ROBERT: Shut up, lefty.

PAT: Or whatever. Maybe there's just—you know, you're just still around because you're like a vestige of what we used to be.

DAVID WOLMAN: Thank you. Thank you. I'll call my—as soon as my kids are old enough, I'll tell them that daddy's a vestige.

PAT: Which sort of brought us back to our original question. Like, why aren't lefties dwindling? And when we pushed David here's what he finally said.

DAVID WOLMAN: I would argue because I'm a lefty and a strong left-hander so, you know, take many, many grains of salt.

ROBERT: You're arguing from pride, we understand that.

DAVID WOLMAN: Of course. No—well, pride and a little bit of research. But I would argue that a splash of diversity within the brain as far as brain organization has had a cumulative beneficial effect for our species. Now if you ...

JAD: How exactly does he mean?

ROBERT: Well, because if conditions on Earth should change radically, nature just likes to have a little variety in the—in the gene pool. So if everyone's doing really well with one set of genes and then the situation changes drastically, you don't want everybody to get sick and die. So in variety there is a slightly heightened chance of survival.

DAVID WOLMAN: I think it's a subtle advantage to the population, but I think—I think there's a beauty to it nevertheless. Lefties are coming at the world from a slightly different angle.

PAT: But this puts David in kind of a weird spot, because even if lefties don't dwindle away, if sports or brain diversity or some other random reason keeps them around, they'll always be the few.

DAVID WOLMAN: You know, as I said in the book, I don't think this is cause for the next march on Washington, but—but lefties are their own special minority group.

ROBERT: Unless you are a parrot.

HUNT SLONEM: This is Coco. He was ...

DAVID WOLMAN: Yes. Somehow I knew you guys would go for the parrot.

PAT: As it turns out ...

DAVID WOLMAN: Parrots seem to be, I think it's 90 percent left-handed or left-footed or left-clawed, left-taloned, whatever I'm supposed to call it.

PAT: Robert and I went to visit this artist named Hunt Slonem who rescues a lot of parrots.

HUNT SLONEM: This is a cockatiel whose name is Crayola.

PAT: And we tested 11 of his birds.

PAT: They told us that the test that they've used before is you put a piece of food on the table or on a platform, and whichever foot they pick it up with is their preferred foot.

HUNT SLONEM: Well, that makes sense.

ROBERT: We would walk up to a cage ...

HUNT SLONEM: This is Clive.

PARROT: Hi!

ROBERT: Hi!

ROBERT: Greets the parrot.

ROBERT: I'm going to give you a potato chip.

ROBERT: Present it with our treat, and then we would wait to see what it did.

PAT: A lefty. We have a lefty.

ROBERT: We went up to another cage, did the same thing.

PAT: Left—left foot.

HUNT SLONEM: Another lefty.

PAT: And in the end ...

ROBERT: The final count was ...

PAT: Okay, well so our final tally was what? Nine to ...

ROBERT: Nine to two to one. Nine lefty, two righty and one went both ways.

JAD: Oh, so that is close to 90 percent.

ROBERT: Close to—yes.

PAT: So if David was a parrot, he would have felt right at home.

JAD: But why do you suppose parrots are 90 to 10 the other way?

ROBERT: I have no—I don't think anybody knows. On the other hand ...

PARROT: Hi.

ROBERT: Hi!

ROBERT: They do—they do talk a lot.

PARROT: [laughs]

HUNT SLONEM: He thinks that's funny.

PARROT: Hi!

HUNT SLONEM: Hi!

PAT: We've incited mayhem.

HUNT SLONEM: Oh, this is nothing. They're on their best behavior.

JAD: Before we close, we have a little sad news. Our producer Pat Walters, Parrot Walters, will be moving on, moving to the left coast after this show.

ROBERT: If you listened to this show over the last new years, you heard all kinds of wonderfully strange and diverse tales.

JAD: Yeah.

ROBERT: That have taken Pat to kinds of different places and put him in all kinds of different moods. And you hate to lose a rainbow, you know? He is one, so ...

JAD: Definitely. Definitely. Pat, we love you. We wish you the very, very best out there.

[SUE: Hello. This is Sue.]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Jonathan Gottschall.]

[DAVID WOLMAN: Hello, this is David Wolman.]

[SUE: Reading you guys the credits.]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Here we go.]

[DAVID WOLMAN: Radiolab is produced by Jad Abumrad.]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Our staff includes ...]

[DAVID WOLMAN: Ellen Horne.]

[SUE: Soren Wheeler.]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Pat Walters.]

[SUE: Tim Howard.]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Brenna Farrell.]

[DAVID WOLMAN: Molly Webster.]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Malissa O'Donnell.]

[SUE: Dylan Keefe, Jamie York, Lynn Levy, Andy Mills and Kelsey Padgett.]

[DAVID WOLMAN: With help from Arianne Wack, Simon Adler ...]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: And Krystnell Storr.]

[SUE: Special thanks ...]

[DAVID WOLMAN: Special thanks ...]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: Special thanks to Sam Bryant ...]

[DAVID WOLMAN: And PJ Vogt. PJ Vogt.]

[JONATHAN GOTTSCHALL: PJ Vogt. Thanks very much.]

[SUE: Okay. Thanks. Bye.]

[DAVID WOLMAN: Bye.]

[ANSWERING MACHINE: End of message.]

-30-

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of programming is the audio record.